Symphony No. 6 (Mahler)

| Symphony No. 6 | |

|---|---|

| by Gustav Mahler | |

Gustav Mahler in 1907 | |

| Key | A minor |

| Composed | 1903–1904: Maiernigg |

| Published |

1906

|

| Recorded | F. Charles Adler, Vienna Symphony Orchestra, 1952 |

| Movements | 4 |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 27 May 1906 |

| Location | Essen |

| Conductor | Gustav Mahler |

Symphony No. 6 in A minor by Gustav Mahler is a symphony in four movements, composed in 1903 and 1904 (revised 1906; scoring repeatedly revised). Mahler conducted the work's first performance at the Saalbau concert hall in Essen on May 27, 1906. It is sometimes referred to by the nickname Tragische ("Tragic"). Mahler composed the symphony at what was apparently an exceptionally happy time in his life, as he had married Alma Schindler in 1902, and during the course of the work's composition his second daughter was born. This contrasts with the tragic, even nihilistic, ending of No. 6. Both Alban Berg and Anton Webern praised the work when they first heard it. Berg expressed his opinion of the stature of this symphony in a 1908 letter to Webern:

"Es gibt doch nur eine VI. trotz der Pastorale." (There is only one Sixth, despite the Pastoral.)[1]

Instrumentation

The symphony is written for a large orchestra comprising:

|

|

- ↑ The sound of the hammer, which features in the last movement, was stipulated by Mahler to be "brief and mighty, but dull in resonance and with a non-metallic character (like the fall of an axe)." The sound achieved in the premiere did not quite carry far enough from the stage, and indeed the problem of achieving the proper volume while still remaining dull in resonance remains a challenge to the modern orchestra. Various methods of producing the sound have involved a wooden mallet striking a wooden surface, a sledgehammer striking a wooden box, or a particularly large bass drum, or sometimes simultaneous use of more than one of these methods.

As in many other of his compositions, Mahler indicates in several places that extra instruments should be added, including two or more celestas "if possible", "several" triangles at the end of the first movement, doubled snare drum (side drum) in certain passages, and in one place in the fourth movement "several" cymbals. While at the beginning of each movement Mahler calls for two harps, at one point in the Andante he calls for "several", and at one point in the Scherzo he writes "4 harps". Often he does not specify a set number, especially in the last movement, simply writing "harps".

While the first version of the score included "whip" or slapstick and tambourine, these were removed over the course of Mahler's extensive revisions.

Nickname of Tragische

The status of the symphony's nickname is problematic. Mahler did not title the symphony when he composed it, or at its first performance or first publication. When he allowed Richard Specht to analyse the work and Alexander von Zemlinsky to arrange the symphony, he did not authorize any sort of nickname for the symphony. He had, as well, decisively rejected and disavowed the titles (and programmes) of his earlier symphonies by 1900. Only the words "Sechste Sinfonie" appeared on the programme for the performance in Munich on November 8, 1906.[2]:59 Nor does the word Tragische appear on any of the scores that C.F. Kahnt published (first edition, 1906; revised edition, 1906), in Specht's officially approved Thematische Führer ('thematic guide')[2]:50 or on Zemlinsky's piano duet transcription (1906).[2]:57 By contrast, in his Gustav Mahler memoir, Bruno Walter claimed that "Mahler called [the work] his Tragic Symphony". Additionally, the programme for the first Vienna performance (January 4, 1907) refers to the work as "Sechste Sinfonie (Tragische)".

Structure

The work, in four movements, lasts around 80 minutes. The order of the inner movements is a matter of debate. The first published edition of the score (CF Kahnt, 1906) featured the movements in the following order:[3]

However, Mahler subsequently placed the Andante as the second movement, and this new order of the inner movements was reflected in the second and third published editions of the score, as well as the Essen premiere.

Scholars such as Norman Del Mar have argued for the Andante/Scherzo order of the inner movements.[2]:43[4] The 1963 Erwin Ratz edition publishes the score with the movements ordered to Mahler's original conception. Del Mar, among others, has criticised the Ratz edition for its lack of documentary evidence to justify the Scherzo/Andante order. In contrast, scholars such as Theodor W. Adorno, Henry-Louis de la Grange, Hans-Peter Jülg and Karl Heinz Füssl have argued for the original order as more appropriate, expostulating on the overall tonal scheme and the various relationships between the keys in the final three movements. Füssl, in particular, noted that Ratz made his decision under historical circumstances where the history of the different autographs and versions was not completely known at the time.[5] Füssl has also noted the following features of the Scherzo/Andante order:[6]

- The Scherzo is an example of 'developing variation' in its treatment of material from the first movement, where separation of the Scherzo from the first movement by the Andante disrupts that linkage.

- The Scherzo and the first movement utilise identical keys, A minor at the beginning and F major in the trio.

- The Andante's key, E♭ major, is farthest removed from the key at the close of the first movement (A major), whilst the C minor key at the beginning of the finale acts as transition from E♭ major to A minor, the principal key of the finale.

British composer David Matthews was a former adherent of the Andante/Scherzo order,[3] but has since changed his mind and now argues for Scherzo/Andante as the preferred order, again citing the overall tonal scheme of the symphony.[7] Matthews, Paul Banks and scholar Warren Darcy (the last an advocate for the Andante/Scherzo order) have independently proposed the idea of two separate editions of the symphony, one to accommodate each version of the order of the inner movements.[3][7]

Formally, the symphony is one of Mahler's most outwardly conventional. The first three movements are relatively traditional in structure and character, with a standard sonata form first movement (even including an exact repeat of the exposition, unusual in Mahler) leading to the middle movements – one a scherzo-with-trios, the other slow. However, attempts to analyze the vast finale in terms of the sonata archetype have encountered serious difficulties. As Dika Newlin has pointed out:

"it has elements of what is conventionally known as 'sonata form', but the music does not follow a set pattern [...] Thus, 'expositional' treatment merges directly into the type of contrapuntal and modulatory writing appropriate to 'elaboration' sections [...]; the beginning of the principal theme-group is recapitulated in C minor rather than in A minor, and the C minor chorale theme [...] of the exposition is never recapitulated at all"[8]

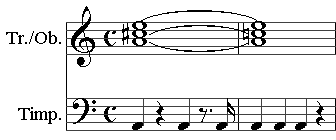

The first movement, which for the most part has the character of a march, features a motif consisting of an A major triad turning to A minor over a distinctive timpani rhythm. The chords are played by trumpets and oboes when first heard, with the trumpets sounding most loudly in the first chord and the oboes in the second.:

Listen

ListenProblems playing this file? See media help.

This motif, which some commentators have linked with fate,[9] reappears in subsequent movements. The first movement also features a soaring melody which the composer's wife, Alma Mahler, claimed represented her. This melody is often called the "Alma theme".[9] A restatement of that theme at the movement's end marks the happiest point of the symphony.

|

Andante Moderato – slow movement from Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 6

Performed by the Virtual Philharmonic Orchestra (Reinhold Behringer) with digital samples |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The scherzo marks a return to the unrelenting march rhythms of the first movement, though in a 'triple-time' metrical context.

Its trio (the middle section), marked Altväterisch ('old-fashioned'), is rhythmically irregular (4

8 switching to 3

8 and 3

4) and of a somewhat gentler character.

According to Alma Mahler, in this movement Mahler "represented the arrhythmic games of the two little children, tottering in zigzags over the sand". The chronology of its composition suggests otherwise. The movement was composed in the summer of 1903, when Maria Anna (born November 1902) was less than a year old. Anna Justine was born a year later in July 1904.

The andante provides a respite from the intensity of the rest of the work. Its main theme is an introspective ten-bar phrase in E♭ major, though it frequently touches on the minor mode as well. The orchestration is more delicate and reserved in this movement, making it all the more poignant when compared to the other three.

The last movement is an extended sonata form, characterized by drastic changes in mood and tempo, the sudden change of glorious soaring melody to deep agony.

The movement is punctuated by three hammer blows.

Alma quoted her husband as saying that these were three mighty blows of fate befallen by the hero, "the third of which fells him like a tree". She identified these blows with three later events in Gustav Mahler's own life: the death of his eldest daughter Maria Anna Mahler, the diagnosis of an eventually fatal heart condition, and his forced resignation from the Vienna Opera and departure from Vienna. When he revised the work, Mahler removed the last of these three hammer strokes so that the music built to a sudden moment of stillness in place of the third blow. Some recordings and performances, notably those of Leonard Bernstein, have restored the third hammer blow.[10] The piece ends with the same rhythmic motif that appeared in the first movement, but the chord above it is a simple A minor triad, rather than A major turning into A minor. After the third 'hammer-blow' passage, the music gropes in darkness and then the trombones and horns begin to offer consolation. However, after they turn briefly to major they fade away and the final bars erupt fff in the minor.

Performance history

There is some controversy over the order of the two middle movements. Mahler conceived the work as having the scherzo second and the slow movement third, a somewhat unclassical arrangement adumbrated in such earlier gargantuan symphonies as Beethoven's No. 9, Bruckner's No. 8 and (unfinished) No. 9, and Mahler's own four-movement No. 1 and No. 4. It was in this arrangement that the symphony was completed (in 1904) and published (in March 1906); and it was with a conducting score in which the scherzo preceded the slow movement that Mahler began rehearsals for the work's first performance, in May 1906. During those rehearsals, however, Mahler decided that the slow movement should precede the scherzo, and he instructed his publishers C.F. Kahnt to prepare a "second edition" of the work with the movements in that order, and meanwhile to insert errata slips indicating the change of order into all unsold copies of the existing edition.

The first occasion after Mahler's death where the conductor reverted to the original movement order seems to have been in 1919, after Alma had sent a telegram to Willem Mengelberg which said "erst Scherzo dann Andante" ("First Scherzo then Andante"). Mengelberg, who had been in close touch with Mahler until the latter's death, and had conducted the symphony in the "Andante/Scherzo" arrangement up to 1916, then switched to the "Scherzo/Andante" order. In this he seems to have been alone: other conductors, such as Oskar Fried, continued to perform (and eventually record) the work as 'Andante/Scherzo', per Mahler's own second edition, right up to the early 1960s.

In 1963, Erwin Ratz's "Critical Edition" of the Sixth appeared, where the Scherzo preceded the Andante. Ratz, however, did not offer documented support, such as Alma Mahler's telegram, for his assertion that Mahler "changed his mind a second time" at some point before his death. One consequence of this edition was that conductors who recorded the work, and with a preference for the revised Andante/Scherzo order, would find their recordings with the middle movements in the order of Scherzo/Andante, in conformity with the 1963 Ratz Edition. The lack of documentary or other evidence in support of Ratz's (and Alma's) reverted ordering has caused the most recent Critical Edition to utilise the Andante/Scherzo order. However, many conductors continue to perform the Scherzo before the Andante, in keeping with Mahler's original order. British conductor John Carewe has noted parallels between the tonal plan of Beethoven's Symphony No. 7 and Mahler's Symphony No. 6, with the Scherzo/Andante order of movements in the latter, where David Matthews has noted that performing the Mahler with the Andante/Scherzo order would damage the structure of the tonal key relationships and remove this parallel.[7] Moreover, Mahler biographer Henry-Louis de La Grange, referring to the 1919 Mengelberg telegram, has questioned the notion of Alma simply expressing a personal view of the movement order:

"It is far more likely ten years after Mahler's death and with a much clearer perspective on his life and career, Alma would have sought to be faithful to his artistic intentions... it is stretching the bounds of both language and reason to describe [Andante-Scherzo] as the 'only correct' one. Mahler's Sixth Symphony, like many other compositions in the repertory, will always remain a 'dual-version' work, but few of the others have attracted quite as much controversy."[11]

The dual-version view is one echoed by another major Mahler writer, Donald Mitchell.

An additional question is on whether to restore the third hammer blow. Both the Ratz edition and the most recent critical edition delete the third hammer blow. However, advocates on opposite sides of the inner movement debate, such as Del Mar and Matthews, have separately argued for restoration of the third hammer blow.[7]

Selected discography

This discography encompasses both audio and video recordings, and classifies them as to the order of the middle movements. Recordings with three hammer blows in the finale are noted with an asterisk.

Scherzo / Andante

- Erich Leinsdorf, Boston Symphony Orchestra, RCA Victor Red Seal LSC-7044

- Jascha Horenstein, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, Unicorn UKCD 2024/5 (live recording from 1966)

- Leonard Bernstein, New York Philharmonic,[12] Sony Classical SMK 60208 (*)

- Vaclav Neumann, Gewandhaus Orchestra Leipzig, Berlin Classics 0090452BC

- George Szell, Cleveland Orchestra, Sony Classical SBK 47654

- Bernard Haitink, Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam, Q-DISC 97014 (live performance from November 1968)

- Rafael Kubelik, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Deutsche Grammophon 289 478 7897-1

- Rafael Kubelik, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Audite 1475671 (live recording of 6 December 1968 performance)

- Bernard Haitink, Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam, Philips 289 420 138-2

- Jascha Horenstein, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, BBC Legends BBCL4191-2

- Georg Solti, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Decca 414 674-2

- Hans Zender, Saarbrücken Radio Symphony Orchestra, CPO 999 477-2

- Maurice Abravanel, Utah Symphony Orchestra, Vanguard Classics SRV 323/4 (LP)

- Herbert von Karajan, Berlin Philharmonic, Deutsche Grammophon 289 415 099-2

- Leonard Bernstein, Vienna Philharmonic, Deutsche Grammophon DVD 440 073 409-05 (live film recording from October 1976) (*)

- James Levine, London Symphony Orchestra, RCA Red Seal RCD2-3213

- Kirill Kondrashin, Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, Melodiya CD 10 00811

- Václav Neumann, Czech Philharmonic, Supraphon 11 1977-2

- Claudio Abbado, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Deutsche Grammophon 289 423 928-2

- Milan Horvat, Philharmonica Slavonica, Line 4593003

- Kirill Kondrashin, SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg, Hänssler Classic 9842273 (live recording from January 1981)

- Lorin Maazel, Vienna Philharmonic, Sony Classical S14K 48198

- Klaus Tennstedt, London Philharmonic Orchestra, EMI Classics CDC7 47050-8

- Klaus Tennstedt, London Philharmonic Orchestra. LPO-0038 (live recording from the 1983 Proms)

- Erich Leinsdorf, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Orfeo C 554 011 B (live recording of 10 June 1983 performance)

- Gary Bertini, Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra, EMI Classics 94634 02382

- Giuseppe Sinopoli, Philharmonia Orchestra, Deutsche Grammophon 289 423 082-2

- Eliahu Inbal, Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, 1986, Denon Blu-spec cd (COCO-73280-1)

- Leonard Bernstein, Vienna Philharmonic, Deutsche Grammophon 289 427 697-2 (*)

- Michiyoshi Inoue, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Pickwick/RPO CDRPO 9005

- Bernard Haitink, Berlin Philharmonic, Philips 289 426 257-2

- Riccardo Chailly, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Decca 444 871-2

- Hartmut Haenchen, Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra, Capriccio 10 543

- Hiroshi Wakasugi, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, 1989, Fontec FOCD9022/3

- Leif Segerstam, Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Chandos CHAN 8956/7

- Christoph von Dohnányi, Cleveland Orchestra, Decca 289 466 345-2

- Klaus Tennstedt, London Philharmonic Orchestra, EMI Classics 7243 5 55294 28 (live recording from November 1991)

- Anton Nanut, Radio Symphony Orchestra Ljubljana, Zyx Classic CLS 4110

- Neeme Järvi, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, Chandos CHAN 9207

- Antoni Wit, Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra, Naxos 8.550529

- Seiji Ozawa, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Philips 289 434 909-2

- Yevgeny Svetlanov, State Symphony Orchestra of the Russian Federation, Warner Classics 2564 68886-2 (box set)

- Emil Tabakov, Sofia Philharmonic Orchestra, Capriccio C49043

- Benjamin Zander, Boston Philharmonic Orchestra, Carlton 6601007

- Edo de Waart, Radio Filharmonisch Orkest, RCA 27607

- Pierre Boulez, Vienna Philharmonic, Deutsche Grammophon 289 445 835-2

- Zubin Mehta, Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Warner Apex 9106459

- Thomas Sanderling, Saint Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra, RS Real Sound RS052-0186

- Yoel Levi, Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, Telarc CD 80444

- Michael Gielen, SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg, Hänssler Classics 93029

- Günther Herbig, Saarbrücken Radio Symphony Orchestra, Berlin Classics 0094612BC

- Michiyoshi Inoue, New Japan Philharmonic, 2000, Exton OVCL-00121

- Benjamin Zander, Philharmonia Orchestra, Telarc CD-80586

- Michael Tilson Thomas, San Francisco Symphony, SFS Media 40382001

- Bernard Haitink, Orchestre National de France, Naïve V4937

- Christoph Eschenbach, The Philadelphia Orchestra, Ondine ODE1084-5B

- Mark Wigglesworth, Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, MSO Live 391666

- Bernard Haitink, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, CSO Resound 210000045796

- Gabriel Feltz, Stuttgart Philharmonic, Dreyer Gaido 9595564

- Vladimir Fedoseyev, Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra of Moscow Radio, Relief 2735809

- Eiji Oue, Osaka Philharmonic Orchestra, Fontec FOCD9253/4

- Takashi Asahina, Osaka Philharmonic Orchestra, Green Door GDOP-2009

- Jonathan Nott, Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, Tudor 7191

- Esa-Pekka Salonen, Philharmonia Orchestra, Signum SIGCD275

- Hartmut Haenchen, Orchestre Symphonique du Théâtre de la Monnaie, ICA Classics DVD ICAD5018

- Antal Doráti, Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Helicon 9699053 (live recording of 27 October 1963 performance)

- Lorin Maazel, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, RCO Live RCO 12101 DVD

- Paavo Järvi, Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, C-Major DVD 729404

- Jukka-Pekka Saraste, Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, Simax PSC1316

- Pierre Boulez, Lucerne Festival Academy Orchestra, Accentus Music ACC30230

- Antonio Pappano, Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, EMI Classics (Warner Classics 5099908441324)

- Lorin Maazel, Philharmonia Orchestra, Signum SIGCD361

- Jaap van Zweden, Dallas Symphony Orchestra, DSO Live

- Libor Pesek, Ceski Narodni Symfonicky Orchestr, Out of the Frame OUT 068

- Vaclav Neumann, Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Exton OVCL-00259

- Zdenek Macal, Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Exton OVCL-00245

- Vladimir Ashkenazy, Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Exton OVCL-00051

- Eliahu Inbal, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, 2007, Fontec SACD (FOCD9369)

- Eliahu Inbal, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, 2013, Exton SACD (OVCL-00516 & OVXL-00090 "one point recording version")

- Gary Bertini, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, Fontec FOCD9182

- Georges Pretre, Wiener Symphoniker, Weitblick SSS0079-2

- Giuseppe Sinopoli, Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra, Weitblick SSS0108-2

- Rudolf Barshai, Yomiuri Nippon Symphony Orchestra, Tobu YNSO Archive Series YASCD1009-2

- Martin Sieghart, Arnhem Philharmonic Orchestra, Exton HGO 0403

- Heinz Bongartz, Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra, Weitblick SSS0053-2

Andante / Scherzo

- Charles Adler, Vienna Symphony Orchestra, Spa Records SPA 59/60

- Eduard Flipse, Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, Philips ABL 3103-4 (LP), Naxos Classical Archives 9.80846-48 (CD)

- Dimitri Mitropoulos, New York Philharmonic,[12] NYP Editions (live recording from 10 April 1955)

- Eduard van Beinum, Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam, Tahra 614/5 (live recording from 7 December 1955)

- Sir John Barbirolli, Berlin Philharmonic, Testament SBT1342 (live recording of 13 January 1966 performance)

- Sir John Barbirolli. New Philharmonia Orchestra, Testament SBT1451 (live recording of 16 August 1967 Proms performance)

- Sir John Barbirolli, New Philharmonia Orchestra, EMI 7 67816 2

- Harold Farberman, London Symphony Orchestra, Vox 7212 (CD)

- Heinz Rögner, Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, Eterna 8-27 612-613

- Simon Rattle, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, EMI Classics CDS5 56925-2

- Glen Cortese, Manhattan School of Music Symphony Orchestra, Titanic 257

- Andrew Litton, Dallas Symphony Orchestra, Delos (live recording, limited commemorative edition)

- Sir Charles Mackerras, BBC Philharmonic, BBC Music Magazine MM251 (Vol 13, No 7) (*)

- Mariss Jansons, London Symphony Orchestra, LSO Live LSO0038

- Claudio Abbado, Berlin Philharmonic, Deutsche Grammophon 289 477 557-39

- Iván Fischer, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Channel Classics 22905

- Mariss Jansons, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, RCO Live RCO06001

- Claudio Abbado, Lucerne Festival Orchestra, Euroarts DVD 2055648

- Simone Young, Hamburg Philharmonic, Oehms Classics OC413

- David Zinman, Tonhalle Orchestra Zürich, RCA Red Seal 88697 45165 2

- Valery Gergiev, London Symphony Orchestra, LSO Live LSO0661

- Jonathan Darlington, Duisberg Philharmonic, Acousence 7944879

- Petr Vronsky, Moravian Philharmonic Orchestra, ArcoDiva UP0122-2

- Fabio Luisi, Vienna Symphony Orchestra, Live WS003

- Vladimir Ashkenazy, Sydney Symphony Orchestra, SSO Live

- Riccardo Chailly, Gewandhaus Orchestra Leipzig, Accentus Music DVD ACC-2068

- Markus Stenz, Gürzenich Orchestra Köln, Oehms Classics OC651

- Daniel Harding, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, BR-Klassik 900132

- Simon Rattle, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, BPH 7558515 (live recording from 1987)

Quotations

"My Sixth will propound riddles the solution of which may be attempted only by a generation which has absorbed and truly digested my first five symphonies."— Mahler, in a letter to Richard Specht

"My Sixth seems to be yet another hard nut, one that our critics' feeble little teeth cannot crack."— Mahler, in a letter to Willem Mengelberg

Premieres

- World premiere: May 27, 1906, Saalbau, Essen, conducted by the composer

- Dutch première: September 16, 1916, Amsterdam, with the Concertgebouw Orchestra conducted by Willem Mengelberg

- American premiere: December 11, 1947, New York City, conducted by Dimitri Mitropoulos

- Recording premiere: F. Charles Adler conducting the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, 1952

References

- ↑ Sybill Mahlke (2008-06-29). "Wo der Hammer hängt Komische Oper". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- 1 2 3 4 Kubik, Reinhold. "Analysis versus history: Erwin Ratz and the Sixth Symphony" (PDF). In Gilbert Kaplan. The Correct Movement Order in Mahler's Sixth Symphony. New York, New York: The Kaplan Foundation. ISBN 0-9749613-0-2.

- 1 2 3 Darcy, Warren (Summer 2001). "Rotational Form, Teleological Genesis, and Fantasy-Projection in the Slow Movement of Mahler’s Sixth Symphony". 19th Century Music. XXV (1): 49–74. JSTOR 10.1525/ncm.2001.25.1.49.

- ↑ Del Mar, Norman, Mahler's Sixth Symphony – A Study. Eulenberg Books (London), ISBN 9780903873291, pp. 34–64 (1980).

- ↑ De La Grange, Henry-Louis, Gustav Mahler: Volume 3. Vienna: Triumph and Disillusion, Oxford University Press (Oxford, UK), p. 816 (ISBN 0-19-315160-X).

- ↑ Füssl, Karl Heinz, "Zur Stellung des Mittelsätze in Mahlers Sechste Symphonie". Nachricthen zur Mahler Forschung, 27, International Gustav Mahler Society (Vienna), March 1992.

- 1 2 3 4 Matthews, David, 'The Sixth Symphony', in The Mahler Companion (eds Donald Mitchell and Andrew Nicholson). Oxford University Press (Oxford, UK), ISBN 0-19-816376-2, pp. 366–375 (1999).

- ↑ Dika Newlin, Bruckner, Mahler, Schoenberg, New York, 1947, pp. 184–5.

- 1 2 "Mahler Symphony No. 6", 2016 program notes, New York Philharmonic

- ↑ Robert Beale (2015-10-02). "Interview with Sir Mark Elder as he prepares to conduct the Halle in a Mahler marathon". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 2015-11-14.

- ↑ De La Grange, Henry-Louis, Gustav Mahler, Volume 4: A New Life Cut Short, Oxford University Press (2008), p. 1587 ISBN 9780198163879

- 1 2 Mahler Symphony No. 6 at the New York Philharmonic, graphic showing movement order and number of hammer blows, 11 February 2016

External links

- Symphony No. 6: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Synoptic survey: Extensive critical analysis of many recordings by Tony Duggan

- MahlerFest XVI, 2003 programme book

- Bruck, Jerry, 'Undoing a "Tragic" Mistake, in The Correct Movement Order in Mahler's Sixth Symphony (Gilbert Kaplan, editor). The Kaplan Foundation, ISBN 0-9749613-0-2 (New York, NY), pp. 13–35.

- Oregon Symphony, programme note, November 2012

- David Matthews, 'The order of the middle movements in Mahler's Sixth Symphony' (website blog entry), January 2016