Early history of Switzerland

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Switzerland |

.svg.png) |

| Early history |

| Old Swiss Confederacy |

|

| Transitional period |

|

| Modern history |

|

| Timeline |

| Topical |

|

|

The early history of Switzerland begins with the earliest settlements up to the beginning of Habsburg rule, which in 1291 gave rise to the independence movement in the central cantons of Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden and the Late Medieval growth of the Old Swiss Confederacy.

Prehistory

Stone Age

Archeological evidence from the Wildkirchli cave in Appenzell suggests that hunter-gatherers settled in the lowlands north of the Alps in the Upper Paleolithic, in Robenhausen settlements dated back to around 8000 BC were found.[1]

In the Neolithic period, the area was relatively densely populated, as is attested to by the many archeological findings from that period. Remains of pile dwellings have been found in the shallow areas of many lakes. The Swiss plateau was dominated by the Linear Pottery culture from the 5th millennium BC; it lay on the south-western outskirts of the Corded Ware horizon in the 3rd millennium BC, evolving into the early Bronze Age Beaker culture. Artifacts dated to the 5th millennium BC were discovered at the Schnidejoch in 2003 to 2005.[2]

Bronze Age

The first Indo-European settlement likely dates to the 2nd millennium, at the latest in the form of the Urnfield culture from c. 1300 BC.

Iron Age

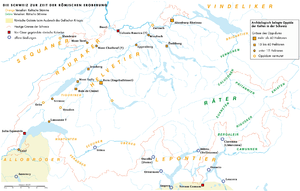

The Swiss plateau lay in the western part of the Early Iron Age Halstatt culture,[3] and it participated in the early La Tène culture (named for the type site at Lake Neuchatel) which arose out of the Hallstatt background from the 5th century BC.[4] In the 1st century BC (late La Tène), the Swiss plateau was occupied by the Helvetii in the west and by the Vindelici in the east, while the Alpine parts of eastern Switzerland were inhabited by the non-Celtic Raetians.

The distribution of La Tène culture burials in Switzerland indicates that the Swiss plateau between Lausanne and Winterthur was relatively densely populated. Settlement centres existed in the Aare valley between Thun and Bern, and between Lake Zurich and the Reuss. The Valais and the regions around Bellinzona and Lugano also seem to have been well-populated; however, those lay outside the Helvetian borders.

Almost all the Celtic oppida were built in the vicinity of the larger rivers of the Swiss plateau. About a dozen oppida are known in Switzerland (some twenty including uncertain candidate sites), not all of which were occupied during the same time. For most of them, no contemporary name has survived; in cases where a pre-Roman name has been recorded, it is given in brackets.[5] The largest were the one in Berne-Engehalbinsel (presumably Brenodurum, the name recorded on the Berne zinc tablet[6]), on the Aare, and the one in Altenburg-Rheinau on the Rhine. Of intermediate size were those of Bois de Châtel, Avenches (abandoned with the foundation of Aventicum as the capital of the Roman province), Jensberg (near vicus Petinesca, Mont Vully, all within a day's march from the one in Berne, the Oppidum Zürich-Lindenhof at the Zürichsee–Limmat–Sihl triangled Lindenhof hill, and the Oppidum Uetliberg, overlooking the Sihl and Zürichseee lake shore. Smaller oppida were at Genève (Genava), Lausanne (Lousonna) on the shores of Lake Geneva, at Sermuz on the upper end of Lake Neuchatel, at Eppenberg and Windisch (Vindonissa) along the lower Aar, and at Mont Chaibeuf and Mont Terri in the Jura mountains, the territory of the Rauraci.

Roman era

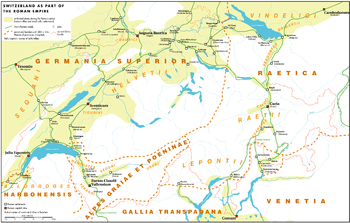

In 58 BCE, the Helvetii tried to evade migratory pressure from Germanic tribes by moving into Gaul, but were stopped and defeated at Bibracte (near modern-day Autun) by Julius Caesar's armies and then sent back. In 15 BCE, Tiberius and Drusus conquered the Alps, and the region became integrated into the Roman Empire:[7] the Helvetii settlement area became part first of Gallia Belgica and later of the province of Germania Superior, while the eastern part was integrated into the Roman province of Raetia.

The following 300 years saw extensive Roman settlement, including the construction of a road network and the founding of many settlements and cities. The center of Roman occupation was at Aventicum (Avenches), other cities were founded at Arbor Felix (Arbon), Augusta Raurica (Kaiseraugst near Basel), Basilea (Basel), Curia (Chur), Genava (Genève), Lousanna (Lausanne), Octodurum (Martigny, controlling the pass of the Great St. Bernard), Salodurum (Solothurn), Turicum (Zürich) and other places. Military garrisons existed at Tenedo (Zurzach) and Vindonissa (Windisch).[7]

The Romans also developed the Great St. Bernard Pass beginning in the year 47, and in 69 part of the legions of Vitellius used it to traverse the Alps. The passes were expanded from dirt trails to narrow paved roads.[7] Between 101 and 260, the legions moved out of the region, allowing trade to expand. In Raetia, Roman culture and language became dominant.[7] Nearly 2,000 years later, some of the population of Graubünden still speak Romansh which is descended from Vulgar Latin.

In 259, Alamanni tribes overran the Limes and caused widespread devastation of Roman cities and settlements. The Roman empire managed to reestablish the Rhine as the border, and the cities on Swiss territory were rebuilt. However, it was now a frontier province, and consequently the new Roman cities were smaller and much more fortified.

Christianization and post-Roman era

In the late Roman period in the 3rd and 4th centuries, the Christianization of the region began. Legends of Christian martyrs such as Felix and Regula in Zürich probably are based on events that occurred during the persecution of Christians under Diocletian around 298. While the story of the Theban Legion, which was martyred near Saint Maurice-en-Valais in Valais, figures into the histories of many towns in Switzerland.[7]

The first bishoprics were founded in the 4th and 5th centuries in Basel (documented in 346), Martigny (doc. 381, moved to Sion in 585), Geneva (doc. 441), and Chur (doc. 451). There is evidence from the 6th century for a bishopric in Lausanne, which maybe had been moved from Avenches.

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Germanic tribes moved in. Burgundians settled in the Jura, the Rhône valley and the Alps south of Lake Geneva; while in the north, Alamannic settlers crossed the Rhine in 406 and slowly assimilated the Gallo-Roman population, or made it retreat into the mountains. Burgundy became a part of the Frankish kingdom in 534; two years later, the dukedom of Alemannia followed suit.

The Burgundy kings furthered the Christianization through newly founded monasteries, e.g. at Romainmôtier or St. Maurice in the Valais in 515. In the Alaman part, only isolated Christian communities continued to exist; the Germanic faith including the worship of Wuodan was prevalent. The Irish monks Columbanus and Gallus re-introduced Christian faith in the early 7th century. The Bishopric of Konstanz also was founded at that time.

Switzerland in the Middle Ages

Early Middle Ages

Under the Carolingian kings, the feudal system proliferated, and monasteries and bishopries were important bases for maintaining the rule. The Treaty of Verdun of 843 assigned the western part of modern Switzerland (Upper Burgundy) to Lotharingia, ruled by Lothair I, and the eastern part (Alemannia) to the eastern kingdom of Louis the German that would become the Holy Roman Empire. The boundary between Alamania, ruled by Louis, and western Burgundy, ruled by Lothar, ran along the lower Aare, turning towards the south at the Rhine, passing west of Lucerne and across the Alps along the upper Rhône to Saint Gotthard Pass.

Louis the German in 853 granted his lands in the Reuss valley to the monastery of St Felix and Regula in Zürich (modern day Fraumünster) of which his daughter Hildegard was the first abbess.[8] According to legend this occurred after a stag bearing an illuminated crucifix between his antlers appeared to him in the marshland outside the town, at the shore of Lake Zürich. However, there is evidence that the monastery was already in existence before 853. The Fraumünster is across the river from the Grossmünster, which according to legend was founded by Charlemagne himself, as his horse fell to his knees on the spot where the martyrs Felix and Regula were buried.

When the land was granted to the monastery, it was exempt from all feudal lords except the king and later the Holy Roman Emperor (a condition known as Imperial immediacy or in German: Reichsfreiheit or Reichsunmittelbarkeit). The privileged position of the abbey (reduced taxes and greater autonomy) encouraged the other men of the valley to put themselves under the authority of abbey. By doing so they gained the advantages of the Imperial immediacy and grew used to the relative freedom and autonomy.[8] The only source of royal or imperial authority was the advocalus or vogt of the abbey which was given to one family after another by the emperor as a sign of trust.

In the 10th century, the rule of the Carolingians waned: Magyars destroyed Basel in 917 and St. Gallen in 926, and Saracenes ravaged the Valais after 920 and sacked the monastery of St. Maurice in 939. The Conradines (von Wetterau) started a long time rule over Swabia during this time. Only after the victory of king Otto I over the Magyars in 955 in the Battle of Lechfeld were the Swiss territories reintegrated into the empire.

High Middle Ages

King Rudolph III of the Arelat kingdom (r. 993–1032) gave the Valais as his fiefdom to the Bishop of Sion in 999, and when Burgundy and thus also the Valais became part of the Holy Roman Empire in 1032, the bishop was also appointed count of the Valais. The Arelat mostly existed on paper throughout the 11th to 14th centuries, its remnants passing to France in 1378, but without its Swiss portions, Bern and Aargau having come under Zähringer and Habsburg rule already by the 12th century, and the County of Savoy was detached from the Arelat just before its dissolution, in 1361.

The dukes of Zähringen founded many cities, the most important being Freiburg in 1120, Fribourg in 1157, and Bern in 1191. The Zähringer dynasty ended with the death of Berchtold V in 1218, and their cities subsequently thus became independent, while the dukes of Kyburg competed with the house of Habsburg over control of the rural regions of the former Zähringer territory. When the house of Zähringen died out in 1218 the office of Vogt over the Abbey of St Felix and Regula in Zurich was granted to the Habsburgs, however it was quickly revoked.[8]

The rise of the Habsburg dynasty gained momentum when their main local competitor, the Kyburg dynasty, died out and they could thus bring much of the territory south of the Rhine under their control. Subsequently, they managed within only a few generations to extend their influence through Swabia in south-eastern Germany to Austria.

Under the Hohenstaufen rule, the alpine passes in Raetia and the St. Gotthard Pass gained importance. Especially the latter became an important direct route through the mountains. The construction of the "Devil’s Bridge" (Teufelsbrücke) across the Schöllenenschlucht in 1198 led to a marked increase in traffic on the mule track over the pass. Frederick II accorded the Reichsfreiheit to Schwyz in 1240[8] in the Freibrief von Faenza in an attempt to place the important pass under his direct control, and his son and for some time co-regent Henry VII had already given the same privileges to the valley of Uri in 1231 (the Freibrief von Hagenau). Unterwalden was de facto reichsfrei, since most of its territory belonged to monasteries, which had become independent even earlier in 1173 under Frederick I "Barbarossa" and in 1213 under Frederick II. The city of Zürich became reichsfrei in 1218.

While some of the "Forest Communities" (Waldstätten, i.e. Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden) were reichsfrei the Habsburgs still claimed authority over some villages and much of the surrounding land. While Schwyz was reichsfrei in 1240, the castle of Neu Habsburg was built in 1244 to help control Lake Lucerne and restrict the neighboring Forest Communities.[8] In 1245 Frederick II was excommunicated by Pope Innocent IV at the Council of Lyon. When the Habsburgs took the side of the pope, some of the Forest Communities took Frederick's side. At this time the castle of Neu Habsburg was attacked and damaged.[8] When Frederick failed against the Pope, those who had taken his side were threatened with excommunication and the Habsburgs gained additional power. In 1273 the rights to the Forest Communities were sold by a cadet branch of the Habsburgs to the head of the family, Rudolf I. A few months later he became King of the Romans, a title that would become Holy Roman Emperor. Rudolph was therefore the ruler of all the reichsfrei communities as well as the lands that he ruled as a Habsburg.

He instituted a strict rule in his homelands and raised the taxes tremenduously to finance wars and further territorial acquisitions. As king, he finally had also become the direct liege lord of the Forest Communities, which thus saw their previous independence curtailed. On the April 16, 1291 Rudolph bought all the rights over the town of Lucerne and the abbey estates in Unterwalden from Murbach Abbey in Alsace. The Forest Communities saw their trade route over Lake Lucerne cut off and feared losing their independence. When Rudolph died on July 15, 1291 the Communities prepared to defend themselves. On August 1, 1291 a Everlasting League was made between the Forest Communities for mutual defense against a common enemy.[8]

In the Valais, increasing tensions between the bishops of Sion and the Counts of Savoy led to a war beginning in 1260. The war ended after the Battle at the Scheuchzermatte near Leuk in 1296, where the Savoy forces were crushed by the bishop's army, supported by forces from Bern. After the peace of 1301, Savoy kept only the lower part of the Valais, while the bishop controlled the upper Valais.

The 14th century

With the opening of the Gotthard Pass in the 13th century, the territory of Central Switzerland, primarily the valley of Uri, had gained great strategical importance and was granted Reichsfreiheit by the Hohenstaufen emperors. This became the nucleus of the Swiss Confederacy, which during the 1330s to 1350s grew to incorporate its core of "eight cantons" (Acht Orte)

The 14th century in the territory of modern Switzerland was a time of transition from the old feudal order administrated by regional families of lower nobility (such as the houses of Bubenberg, Eschenbach, Falkenstein, Freiburg, Frohburg, Grünenberg, Greifenstein, Homberg, Kyburg, Landenberg, Rapperswil, Toggenburg, Zähringen etc.) and the development of the great powers of the late medieval period, primarily the first stage of the meteoric rise of the House of Habsburg, which was confronted with rivals in Burgundy and Savoy. The free imperial cities, prince-bishoprics and monasteries were forced to look for allies in this unstable climate, and entered a series of pacts. Thus, the multi-polar order of the feudalism of the High Middle Ages, while still visible in documents of the first half of the 14th century such as the Codex Manesse or the Zürich armorial gradually gave way to the politics of the Late Middle Ages, with the Swiss Confederacy wedged between Habsburg Austria, the Burgundy, France, Savoy and Milan. Berne had taken an unfortunate stand against Habsburg in the battle of Schosshalde in 1289, but recovered enough to confront Fribourg (Gümmenenkrieg) and then to inflict a decisive defeat on a coalition force of Habsburg, Savoy and Basel in the battle of Laupen in 1339. At the same time, Habsburg attempted to gain influence over the cities of Lucerne and Zürich, with riots or attempted coups reported for the years 1343 and 1350 respectively. This situation led the cities of Lucerne, Zürich and Berne to attach themselves to the Swiss Confederacy in 1332, 1351, and 1353 respectively.

As elsewhere in Europe, Switzerland suffered a crisis in the middle of the century, triggered by the Black Death followed by social upheaval and moral panics, often directed against the Jews as in the Basel massacre of 1349. To this was added the catastrophic 1356 Basel earthquake which devastated a wide region, and the city of Basel was destroyed almost completely in the ensuing fire.

The balance of power remained precarious during the 1350s to 1380s, with Habsburg trying to regain lost influence; Albrecht II besieged Zürich unsuccessfully, but imposed an unfavourable peace on the city in the treaty of Regensburg. In 1375, Habsburg tried to regain control over the Aargau with the help of Gugler mercenaries. After a number of minor clashes (Sörenberg, Näfels), it was with the decisive Swiss victory at the battle of Sempach 1386 that this situation was resolved. Habsburg moved its focus eastward and while it continued to grow in influence (ultimately rising to the most powerful dynasty of Early Modern Europe), it lost all possessions in its ancestral territory with the Swiss annexation of the Aargau in 1416, from which time the Swiss Confederacy stood for the first time as a political entity controlling a contiguous territory.

Meanwhile, in Basel, the citizenry was also divided into a pro-Habsburg and an anti-Habsburg faction, known as Sterner and Psitticher, respectively. The citizens of greater Basel bought most of the privileges from the bishop in 1392, even though Basel nominally remained the domain of the prince-bishops until the Reformation it was de facto governed by its city council, since 1382 dominated by the city's guilds, from this time. Similarly, the bishop of Geneva granted the citizenry substantial political rights in 1387. Other parts of western Switzerland remained under the control of Burgundy and Savoy throughout the 14th century; the Barony of Vaud was incorporated into Savoy in 1359 and was annexed by Berne only in the context of the Swiss Reformation, in 1536.

In the Valais, the bishop of Sion, allied with Amadeus VI, Count of Savoy, was in conflict of the Walser-settled upper Valais during the 1340s. Amadeus pacified the region in 1352, but there was renewed unrest in 1353. In 1355, the towns of the upper Valais formed a defensive pact and negotiated a compromise peace treaty in 1361, but there was a renewed uprising with the 1383 accession of Amadeus VII, Count of Savoy. Amadeus invaded the Valais in 1387, but after his death in a hunting accident, his mother, Bonne de Bourbon, made peace with the Seven Tithings of the upper Valais, restoring the status quo ante of 1301. From this time, the upper Valais was mostly independent de facto, preparing the Republican structure that would emerge in the early modern period. In the Grisons, similar structures of local self-government arose at the same time, with the League of God's House founded in 1367, followed by the Grey League in 1395, both in response to the expansion of the House of Habsburg.

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ Wildkirchli in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ↑ Associated Press (2006-01-18). "5000 Jahre alter Pfeilbogen im Berner Oberland gefunden" (in German). NZZ. Retrieved 2008-11-14. In a later NZZ article (21 August 2008), the date is revised to c.4500BC instead of c.3000BC (in German)

- ↑ N. Müller-Scheeßel, Die Hallstattkultur und ihre räumliche Differenzierung. Der West- und Osthallstattkreis aus forschungsgeschichtlicher Sicht (2000)

- ↑ La Tène Site description(in French)

- ↑ Andres Furger-Gunti: Die Helvetier: Kulturgeschichte eines Keltenvolkes. Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zürich 1984, 50–58.

- ↑ Bern, Engehalbinsel, Römerbad

- 1 2 3 4 5 Encyclopædia Britannica Online: Roman Switzerland accessed November 13, 2008

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Switzerland". Encyclopædia Britannica. 26. 1911. p. 247. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

Bibliography

- Im Hof, U.: Geschichte der Schweiz, Kohlhammer, 1974/2001. ISBN 3-17-017051-1

- Schwabe & Co.: Geschichte der Schweiz und der Schweizer, ISBN 3-7965-2067-7

External links

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Origins of the Confederation, up to 1291. |