Swiss regiment de Karrer

| Régiment suisse de Karrer 1719-1752 de Hallwyl 1752-1763 | |

|---|---|

|

Company colour of Régiment de Karrer | |

| Active | 1719-1763 |

| Country | Old Swiss Confederacy |

| Allegiance | Kingdom of France |

| Branch | Marines |

| Type | Colonial infantry |

| Role | Garrison infantry |

| Size | Five companies |

| Part of | Royal French Navy |

| Depot and garrisons | Rochefort, Martinique, Saint-Domingue, Louisbourg, Québec, Louisiana |

| Motto(s) | Fidelitate & honore, Terra & Mari |

| Engagements |

War of the Austrian Succession Seven Year's War |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Franz Adam Karrer 1719 Ludwig Ignaz Karrer 1736 Franz Josef von Hallwyl 1752 |

| Insignia | |

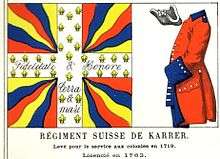

| Company colour of Régiment de Hallwyl |

|

The Swiss regiment de Karrer (from 1752 de Hallwyl) was a Swiss foreign regiment in French colonial service 1719-1763.

Overview

The regiment de Karrer was raised in 1719 by Franz Adam Karrer, a Swiss officer in French service, for the French army. Two years later it was transferred to the French Navy for service in the colonies. Ludwig Ignaz Karrer succeeded his father as colonel-proprietor in 1736. At his death in 1752, Franz Josef von Hallwyl became the last colonel-proprietor. The officers of the regiment were Swiss; the men were recruited in Switzerland and Germany.[1]

Organization

Originally the regiment contained three companies: the colonel's company constituted the depot in Rochefort; the second company was stationed on Martinique; the third company on Saint-Domingue. Detachment from the colonel's company was sent to the Louisbourg fortress in Acadia; 50 men in 1722, 100 men in 1724; 150 men from 1741 until the fortress' surrender in 1745. Soldiers from de Karrer was at the heart of the mutiny at Louisbourg in 1744. A small detachment of 30 men served at Québec 1747-1749. A fourth company was raised in 1731, and became stationed in Louisiana until 1764. A fifth company was raised in 1752 and sent to Saint-Domingue. The regiment was disbanded in 1763.[2]

Legal status and privileges

The officers and men of the regiment did not owe personal allegiance to the King of France; only to the colonel-proprietor, who also signed the officers' commissions. The colonel-proprietor had entered a capitulation with the King, through the secretary of state for the navy, in which he put the regiment, its officers and men, into French service. It was the colonel-proprietor that had promised collective fidelity for himself and his regiment to the King. The capitulation was a legal contract, renewable every ten years, where the terms of both parties were carefully stipulated. As a foreign regiment, the regiment enjoyed a number of privileges. Liberty of conscience was guaranteed, which meant that protestants could be recruited; protestant officers and men were not obliged to participate in catholic ceremonies. The regiment had its own legal jurisdiction, and its members could only be tried by its own court-martial, even when being accused of crimes against civilians.[3] The privileges of the regiment often triggered conflicts with local military and civilian authorities.[4] The mutiny of 1744 was an expression of the foreign soldiers will to defend their special status from infringements. [5]

Uniforms

The regiment wore red coats with blue lapels with white buttonholes, blue cuffs, lining, waistcoats, breeches, and hose (white from 1739), and white buttons. The drummers wore the colonel-proprietors' livery, not the king's, and the drums were decorated with the colonel's coat of arms.[2]

Regimentals 1734.

Regimentals 1734. Regimentals 1740.

Regimentals 1740.

See also

References

- ↑ B. A. Balcom, "Notes on the Karrer Detachement at Louisbourg", The Huissier, July 4, 2004.

- 1 2 René Chartrand, The French Soldier in Colonial America (Bloomfield, Ont.: Museum Restoration Service, 1984).

- ↑ Margaret Fortier, "Karrer Regiment", The Ile Royale Garrison 1713-1745 (Fortress of Louisborg: Report H E 15).

- ↑ Eric Krause, Carol Corbin & William O'Shea, Aspects of Louisbourg: Essays on the History of an Eighteenth Century French Community in North America (Sydney: The University College of Cape Breton University Press, 1995), p. 71.

- ↑ History of Nova Scotia, Book 1, Part 4, Chapter 2 Retrieved 2017-02-10.