Sway, Hampshire

| Sway | |

|---|---|

Sway: Forest Heath Hotel and the post office | |

Sway | |

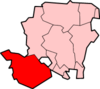

| Sway shown within Hampshire | |

| Population | 3,448 (2001 and 2011 Census')[1] |

| OS grid reference | SZ2798 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LYMINGTON |

| Postcode district | SO41 |

| Dialling code | 01590 |

| Police | Hampshire |

| Fire | Hampshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| EU Parliament | South East England |

| UK Parliament | |

Sway is a village and Civil parish in Hampshire in the New Forest national park in England. The civil parish was formed in 1879, when lands were taken from the extensive parish of Boldre. The village has shops and pubs, and a railway station on the main line from Weymouth and Bournemouth to Southampton and London Waterloo. Sway is on the southern edge of the woodland and heathland of the New Forest. Much of the children's novel The Children of the New Forest is set in the countryside surrounding Sway.

Overview

Sway has shops, two pubs, and a number of restaurants and hotels.[3] There is also a Church of England primary school.[3] The village is home to football clubs,[4][5] a tennis club,[6] the mighty Sway Cricket Club,[7] a fencing club,[8] an archery club,[9] and a gardening club.[10] Sway railway station is on the main line from Weymouth and Bournemouth to Southampton and London Waterloo with train services operated by South West Trains. From Brockenhurst, one can catch the "Lymington Flyer" services connect with the ferry to Yarmouth on the Isle of Wight. Sway is twinned with the village of Bretteville, France.[11]

The northern part of the parish contains areas of woodland, heathland, acid grassland, scrub and valley bog, supporting a richness and diversity of wildlife.[12]

History

Sway is a settlement of Anglo-Saxon origin, and its name, from the Old English name "Svieia", means "noisy stream" which is a probable reference to the Avon Water.[13] Stone Age implements have been found here and Bronze Age barrows containing funerary urns.[13]

Sway is listed four times in the Domesday Book of 1086.[14] Two hides were held from Roger de Montgomerie, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury by Fulcoin and Nigel respectively. A certain Edmund at the same date was holding one hide in Sway which Algar had held from King Edward. Romsey Abbey also held one hide in Sway.

Some time prior to 1150 Hugh de Witteville gave "his whole land of Sway with its men and one mill" to Quarr Abbey, and about the same date Ralph Fulcher donated land at Sway to the same abbey.[15] In the 13th century Christchurch Priory also gained land in Sway, which increased in the 14th century by the grant of land in Sway from John, vicar of Christchurch.[15] Free warren in Sway was granted to the priory in 1384. Romsey Abbey also held land in Sway, afterwards known as the manor of Sway Romsey or South Sway.[15] The Abbess of Romsey was holding land in Sway together with the Abbot of Quarr and the Prior of Christchurch in 1316.[15]

In 1543, at the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the lands possessed by Quarr and Christchurch were granted to Sir John Williams and others, by whom it was subsequently conveyed to John Mill, the purchaser and grantee of much monastic property in the neighbourhood.[15] The combined lands became known as the manor of Sway Quarr. The manor of Sway Romsey (South Sway) remained separate but were also granted at the Dissolution to Sir John Williams and henceforth had the same owners as Sway Quarr.[15] The estate then followed the descent of Battramsley manor until 1627, when it was sold by George Wroughton to John Button of Buckland Lymington, and in 1670 he or his son appeared before the justice seat held at Lyndhurst as the lord of the manor of Sway.[15] Before the end of the 17th century, however, it had passed to Edmund Dummer of Swaythling.[15] It then passed by inheritance into the Bond family who held the estate down to the 19th century.[15]

One other Domesday Book manor within the parish of Sway is known as Arnewood, which prior to 1066 had been held by Siward from Earl Tostig.[16] The estate seems to have belong to Christchurch Manor in the 13th and 14th centuries, although one small part of it was held differently and later became joined to the nearby manor of Ashley to become "Ashley Arnewood".[16] In 1384 the Earl of Salisbury and lord of Christchurch sold the manor of Arnewood to Thomas Street.[16] The manor passed through various hands in the following centuries, but by the 19th century it belonged, like the other manors of Sway, to the Bond family.[16]

St Luke's Church was built in 1839.[17] The ecclesiastical parish of Sway was created in 1841.[18] The civil parish of Sway was formed in 1879, when 2,200 acres (8.9 km2) were taken from the extensive parish of Boldre.[15][19] The railway came to Sway in 1888, when Sway railway station was built.[20]

In the village was Arnewood House (now destroyed by fire) which was the home of the Children of the New Forest in Captain Marryat's book.[13] Marryat also used the surrounding countryside as the setting for the book.[20]

In World War II, an Emergency Landing Ground for aircraft was established just south of the village, and was used by aircraft based at RAF Christchurch for overnight stays to protect them from German attack at Christchurch.[21] However, the Luftwaffe bombed Sway on several occasions, and by 1941, after just one year of operation, the site was abandoned.[21]

Sway Tower

Sway is perhaps best known for Sway Tower. It is 66 metres (200 ft) tall and is a Grade II listed building. It is also known as "Peterson's Folly"

Built by Andrew Thomas Turton Peterson on his private estate from 1879–1885, its design (and the use of concrete) was influenced by the follies Peterson had seen during his time in India. It is constructed entirely out of concrete made with Portland cement, with only the windows having iron supports. It remains the tallest non-reinforced concrete structure in the world.

It was originally designed as a mausoleum, with a perpetual light at the top. However this was not allowed by Trinity House, as it was thought the light would confuse shipping.[22] It also served to publicise the superiority of Portland cement; even then not fully accepted.[23]

The tower is visible from much of the New Forest, and most of the western Solent. A smaller 50-foot (15 m) folly, built as a 'prototype', stands in a group of trees to the north of the taller tower. There are many small concrete features (mainly walls) to be found in Milford, Sway and Hordle.

References

- ↑ "2001 Census Neighbourhood Statistics – Civil Parishes in the New Forest". www.neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ↑ http://www.sway-pc.gov.uk/

- 1 2 Sway Village, Sway Parish Council, retrieved, 18 July 2011

- ↑ Sway Football Club, retrieved 18 July 2011

- ↑ Sway Junior Football Club, retrieved 18 July 2011

- ↑ Sway Lawn Tennis Club

- ↑ Sway Cricket Club, retrieved 2 June 2012

- ↑ Sway Fencing Club, retrieved 18 July 2011

- ↑ Sway Bowmen, retrieved 18 July 2011

- ↑ Gardening Club, retrieved 18 July 2011

- ↑ Sway – Bretteville Friendship Link, retrieved 10 July 2011

- ↑ Hampshire Treasures, Volume 5 (New Forest), Sway, page 303

- 1 2 3 Sway, www3.hants.gov.uk, retrieved 10 July 2011

- ↑ Domesday Map, Place: Sway

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Victoria County History, (1911), A History of the County of Hampshire: Volume 4 – Boldre, Pages 616–623

- 1 2 3 4 Victoria County History, (1912), A History of the County of Hampshire: Volume 5, Hordle, Pages 110–115

- ↑ About St Luke's Church, retrieved 10 July 2011

- ↑ "Sway is a parish formed in 1841 out of Boldre. The church of St. Luke was built in 1839 and restored in 1870." – John Charles Cox, (1904), Hampshire, page 208. Methuen.

- ↑ "Sway [has] been separated by Provisional Order from the parish of Boldre and added to the Lymington Union as a separate parish under the name of the parish of Sway." Reports from Commissioners, Inspectors, and Others. Local Government Board. 1878–1879.

- 1 2 Village of Sway, newforestvillages.4t.com, retrieved 10 July 2011

- 1 2 Sway Airfield, Hampshire Airfields, retrieved 2 December 2013

- ↑ JAMES, J. All about Sway Tower. Lymington, Lymington Museum Trust, 1997.

- ↑ Trout, Edwin. Sway Tower: An early example of high-rise concrete construction Concrete, October 2002 64-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sway, Hampshire. |

- Sway Parish Council

- Sway Village Portal

- Sway Village Design Statement

- Sway Tower, BBC Hampshire & Isle of Wight