Suzanne Valadon

| Suzanne Valadon | |

|---|---|

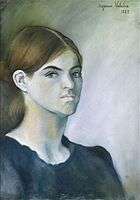

Valadon as a young woman | |

| Born |

Marie-Clémentine Valadon 23 September 1865 Bessines-sur-Gartempe, France |

| Died |

7 April 1938 (aged 72) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Painter and artist's model |

| Movement | Postimpressionism, Symbolism |

Suzanne Valadon (23 September 1865 – 7 April 1938) was a French painter and artists' model who was born Marie-Clémentine Valadon at Bessines-sur-Gartempe, Haute-Vienne, France. In 1894, Valadon became the first woman painter admitted to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. She was also the mother of painter Maurice Utrillo. The subjects of her drawings and paintings included mostly female nudes, female portraits, still lifes, and landscapes. She never attended the academy and was never confined within a tradition.[1] Valadon spent nearly 40 years of her life as an artist.[2]

Personal life

Valadon grew up in poverty with her mother, an unmarried laundress; she did not know her father. Known to be quite independent and rebellious, she attended primary school until age 11. In 1883, aged 18, Valadon gave birth to her illegitimate son, Maurice Utrillo.[2] Valadon’s mother cared for Maurice while she returned to modelling.[3] Valadon's friend Miguel Utrillo would later sign papers recognizing Maurice as his son, although his true paternity is uncertain.[4] Valadon helped to educate herself in art by reading Toulouse-Lautrec’s books and observing the artists at work for whom she posed.[1] In 1893, Valadon began a short-lived affair with composer Erik Satie, moving to a room next to his on the Rue Cortot. Satie became obsessed with her, calling her his Biqui, writing impassioned notes about "her whole being, lovely eyes, gentle hands, and tiny feet", but after six months she left, leaving him devastated.[5] Valadon married stockbroker Paul Moussis in 1895, leading a bourgeois life for 13 years at an apartment in Paris and a house in the outlying region.[6] In 1909, Valadon began an affair with the painter André Utter, age 23 and a friend of her son, divorcing Moussis in 1913.[7] Valadon married Utter in 1914,[8] and he managed her career as well as her son's.[9] Valadon and Utter regularly exhibited work together until the couple divorced in 1934.[9] Art historian, Patricia Mathews, cites how Valadon was well known during her lifetime but within the art historical narrative her work has long been overshadowed by a Bohemian and lower class lifestyle.[10]

Career

Valadon began working at age 11 in a variety of areas including a milliner’s workshop, a factory making funeral wreaths, a market selling vegetables, a waitress, and then finally in the circus.[11] At the age of 15 Valadon met, Count Antoine de la Rochefoucauld and Thèo Wagner, two symbolist painters who were involved in decorating circus belonging to Medrano. Through this connection she began work at the Mollier circus as an acrobat, but a year later, a fall from a trapeze ended that career. The circus was frequented by artists such as Lautrec, Sescau and Berthe Morisot and it is believed this is where Morisot did her painting of Valadon.[12]

In the Montmartre quarter of Paris, she pursued her interest in art, first working as a model for artists, observing and learning their techniques, before becoming a noted painter herself.[13]

Model

Valadon debuted as a model in 1880 in Montmartre at age 15.[14] She modelled for over 10 years for many different artists including the following: Pierre-Cécile Puvis de Chavannes, Théophile Steinlen, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.[2] She modelled under the name “Maria” eventually being nicknamed “Suzanne” after the biblical story of Susanna and the Elders.[15] She was considered a very focused, ambitious, rebellious, determined, self-confident, and passionate woman.[3] In the early 1890s she befriended Edgar Degas who, impressed with her bold line drawings and fine paintings, purchased her work and encouraged her; she remained one of his closest friends until his death. It is believed by art historian, Heather Dawkins, that Valadon's experience as a model added depth to her own images of nude women, which tended to be less idealized than that of the male post impressionists representations.[16]

The most recognizable image of Valadon would be in Renoir's Dance at Bougival from 1883, the same year that she posed for City Dance.[17] In 1885, Renoir painted her portrait again as Girl Braiding Her Hair. Another of his portraits of her in 1885, Suzanne Valadon, is of her head and shoulders in profile. Valadon frequented the bars and taverns of Paris with her fellow painters, and she was Toulouse-Lautrec's subject in his oil painting The Hangover.[18]

Artist

It is commonly believed that Valadon taught herself how to draw at the age of nine.[19] Valadon painted still lifes, portraits, flowers, and landscapes that are noted for their strong composition and vibrant colors. She was, however, best known for her candid female nudes that depict women's bodies from a woman's perspective.[20] This is particularly important because it was unusual in the nineteenth century for a woman artist to make female nudes her primary subject matter.[21] Valadon was not confined to a specific style, yet both Symbolist and Post-Impressionist aesthetics are clearly seen within her work.[22]

Accomplishments

Her second portrait was created in 1883 at age 18 before she gave birth to her son.[23] She produced mostly drawings from 1883-1893 and began painting in 1892. Her first models were her family members, often her son, mother, or niece.[24] Her first female nude was also made in 1892.[25] Her first exhibitions, held in the early 1890s, consisted mostly of portraits, for example of Erik Satie 1893. She regularly showed work at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune in Paris.[26] Valadon’s first time in the Salon de la Nationale was in 1894. Degas was notably the first person to buy drawings from her.[27] Degas also taught her the skill of soft-ground etching.[28]

In 1896, Valadon became a full-time painter after her marriage to Paul Moussis.[8] She made a shift from drawing to painting starting in 1909.[29] Her first large oils for the Salon related to sexual pleasure, and they were some of the first examples in painting for the man to be an object of desire by a woman. These notable Salon paintings include Adam et Eve (Adam and Eve) (1909), La joie de vivre (Joy of Living) (1911), Lancement du filet (Casting of the Net) (1914).[30] Valadon produced around 300 drawings and over 450 oil paintings by the end of her life.[29]

Today, some of her works may be seen at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, the Museum of Grenoble, and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Style

Valadon primarily worked with oil paint, oil pencils, pastels, and red chalk; she did not use ink or watercolor because these media were too fluid for her preference.[6] Valadon’s paintings feature rich colors and bold, open brushwork often featuring firm black lines to define and outline her figures.[2] She used hard black lines to emphasize the structure of the body. She also used firm lines in her nudes to emphasize the play of light on curves.[4]

Valadon’s self-portraits, portraits, nudes, landscapes, and still life's remain detached from trends and aspects of academic art.[31] The subjects of Valadon’s paintings often reinvented the old master’s themes: women bathing, reclining nudes, and interior scenes. However the nudes Valadon paints veer far from the norms of this male dominated genre, the paintings are interpreted in a much different way which could contradict of question the nature of the genre.[10] Many have suggested a vibrant, emotional sense that emanates from her drawings and paintings as a result from an intimate, familiar observation of these women’s bodies. Similarly to Valadon, Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt painted mostly women, yet because of their middle class status in French society at the time they were unable to paint the nude body, regardless of gender.[10] Valadon also emphasized her focus on the importance of composition of her portraits over painting expressive eyes.[6] Her later works, such as Blue Room (1923), are brighter in color and show a new emphasis on decorative backgrounds and patterned materials.[32]

It’s thought that her experience as a model and as an artist allowed her to analyze the process that transformed and positioned the body as an object of the gaze within a work of art and influenced her understanding and perspective of women and the female body.[33] Suzanne Valadon has been considered transgressive in her position as a woman painting the nude female body.[34] Her class allowed her to enter the male public domain of art through modeling and then emerged as an artist within her circle of prominent male artists. She resists typical depictions of women via their class and supposed sexuality through her use of unidealized and self-possessed bodies that are not overly sexualized.[35]

Group Exhibitions

1894, Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, Paris; 1907, Galerie Eugène Blot, Paris;

1909, 1910, 1911, Salon d'Automne, Grand Palais, Paris;

from 1911, 1926 (retrospective), Salon des Indépendants, Paris;

1917, Utrillo, Valadon, Utter, Galerie Berthe Weill, Paris;

1920, Second Exhibition of Young French Painting, Galerie Manzy Joyant, Paris;

1921, Young Painting, Palais d'Ixelles;

1927 and 1928, Salon des Tuileries, Paris;

from 1933 and regularly, Salon des Femmes Artistes Modernes, Paris.

After her death: 1940, 22nd Biennale Internationale des Beaux-Arts, Paris;

1949, Great Trends in Contemporary Painting from Manet to our Day, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyons; 1961, Maurice Utrillo V. Suzanne Valadon, Haus der Kunst, Munich;

1964, Documenta, Kassel;

1969, 14th Salon de Montrouge;

1976, Women Artists (1550-1950), Los Angeles County Museum of Art;

1979, Maurice Utrillo, Suzanne Valadon, Musée Toulouse-Lautrec,

Albi; 1991, Utrillo, Valadon, Utter, Chateau Constant, Bessines;

1991, Utrillo, Valadon, Utter : la Trilogie Maudite, Acropolis, Nice.

Solo Exhibition

1911, the first, at the Galerie Clovis Sagot;

1915, 1919, 1927 (retrospective) and 1928, Galerie Berthe Weill, Paris;

1922, 1923 and 1929, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris;

1928, Galerie des Archers, Lyons;

1929 and 1937, Galerie Bernier, Paris;

1931 and 1932, Galerie Le Portique, Paris;

1931, Galerie Le Centaure, Brussels;

1932, retrospective with a preface by Édouard Herriot, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris.

1938, 1942, 1947, 1959 and 1962, Galerie Pétridès, Paris;

1939 and 1947, Galerie Bernier, Paris;

1948, Tribute to Suzanne Valadon, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris;

1956, The Lefevre Gallery, London;

1967, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris;

1996, Suzanne Valadon, Pierre Gianada Foundation, Martigny.

Permanent Collections

Albi: Still-life with Stemmed Glass

Algiers: Rue Cortot

Belgrade: Still-life, Flowers and Striped Cloth

Bern (Kunstmus.): Duck Eggs (1931, on loan from the Fondation Im Obersteg)

Besançon (MBA et d'Archéologie): Duck (1930)

Cambrai (MBA): Portrait of Madame Lévy (1922, on loan from the Musée national d'Art moderne in Paris)

Cologne (Wallraf-Richartz Mus.): Portrait of a Woman (1925-1928)

Geneva (Petit Palais): After the Bath (1908, pastel); The Future Revealed, or the Fortune Teller (1912); Woman with Double Bass (c. 1914-1915); Standing Nude with Long Hair (1916, pencil); Nude Lying on a Red Sofa (1920); Nude with Drapery (1920)

Limoges (Mus. Municipal de L'Évêché): Nude Girl and Servant (1896, red chalk); Couturier (1914); Bouquet of Flowers with Embroidered Mat (1930, on loan from the Musée national d'Art moderne in Paris)

Lyons: Berthe and her Daughter with Doll

Lyons (MBA): Toilette (1908, pencil and pastel); Marie Coca and her Daughter Gilberte (1914)

Monte Carlo: Portrait of Mauricia Gustave-Coquiot

Nancy (MBA): Woman with White Stockings (1924)

New York (Metropolitan Mus. of Art): After the Bath (1893, pencil); Nude Young Girl Sitting at her Toilette (c. 1895, pencil); Joie de Vivre (1911); Reclining Nude (1928)

New York (MoMA): Children's Bath in the Garden (1910, drawing)

Paris (MAMVP): Mother and Child (c. 1900, wax crayon); Maurice Utrillo at his Easel (1919, oil on canvas); Nude beside the Bed (1922, oil on canvas); Violin Case (1923); Still-life with Drapery and Bunch of Carnations (1924)

Paris (MNAM-CCI): Portrait of the Artist (1883, pastel); The Grandmother (1883, red chalk); Maurice Utrillo as a Child (1896, red chalk); Young Girl Crocheting (c. 1892); Maurice Utrillo Naked, Sitting on a Divan (1895, pencil); Two Nudes: Woman Sitting, Woman Lying down (1897, charcoal); Portrait of the Artist (1903, red chalk); Nude Girl Sitting on the Ground, her Legs Stretched out (1894, charcoal and gouache); Self-portrait (1903, red chalk); Female Nude Sitting on a Towel (1908, charcoal and pastel); Female Nude Getting out of the Bath near an Armchair (c. 1908, charcoal and red chalk); Nude Model Standing and Woman Cleaning a Bath (c. 1908, charcoal); André Utter, Nude, from the Front (c. 1909, charcoal); Adam and Eve (1909); Neither Black nor White, or After the Bath (1909); Maurice Utrillo, his Grandmother and his Dog (1910); Portrait of Maurice Utrillo, his Head Resting on his Fist, or Utrillo Thinking (1911, charcoal on tracing paper); Still-life with Teapot (1911, charcoal); André Utter, Standing Nude (1911, charcoal, study for 'La joie de vivre'); Portrait of the Artist's Mother (1912); Two Studies of Nudes, or Nudes in the Mirror (1914, charcoal and pastel); Couturier (1914); Casters of Nets or Casting the Net (1914); Flowers (1920); Portrait of the Utter Family (c. 1921); Woman at her Chest of Drawers (1922); Portrait of Miss Lily Walton (1922); Portrait of Madame Nora Kars (1922); House in a Garden (Château de Sogalas, Basses-Pyrénées) (1923); Blue Room (1923); Female Nude Standing Holding a Palette (1927, charcoal, study for a poster); Village of Saint-Bernard, Ain (1929)

Paris (Mus. de Montmartre): Self-portrait (1894, pencil and pen)

Paris (Mus. du Petit Palais): Nude with Striped Blanket (1922); Violin

Pittsburgh (Carnegie MA): Tree at Montmagny Quarry (c. 1910, oil on canvas); Woman Combing Her Hair (1905, crayon)

Prague: Flowers

San Francisco (FAM): Toilette de deux enfant dans le jardin (1910); Toilette de Petit garcon (1908); Femme en buste, les mains jointes

Sannois (Musée Utrillo-Valadon): Family Portrait (1913, pencil)

Washington DC (National Mus. of Women In the Arts): Nude Doing his Hair (c. 1916); Abandoned Doll (1921); Bathing the Children in the Garden (1910, etching and dry-point on paper); Bouquet of Flowers in an Empire Vase (1920, oil on canvas); Girl on a Small Wall (1930, oil on canvas)

Death

Suzanne Valadon died of a stroke[36] on 7 April 1938, at age 72, and was buried in the Cimetière de Saint-Ouen in Paris. Among those in attendance at her funeral were her friends and colleagues André Derain, Pablo Picasso, and Georges Braque.

Novels and plays

A novel based on her life by Elaine Todd Koren was published in 2001, entitled Suzanne: of Love and Art.[37] An earlier novel by Sarah Baylis, entitled Utrillo's Mother, was published first in England and later in the United States. Timberlake Wertenbaker's play The Line (2009) traces the relationship between Valadon and Degas. Valadon was the basis for the character Suzanne Rouvier in the novel "The Razor's Edge" by W. Somerset Maugham[38]

Honors

Both an asteroid (6937 Valadon) and a crater on Venus are named in her honor.

The small square at the base of the Montmartre funicular in Paris is named Place Suzanne Valadon.

Gallery

Artwork by Valadon

Self-Portrait, 1883, by Suzanne Valadon

Self-Portrait, 1883, by Suzanne Valadon My Son at 7 Years Old, by Suzanne Valadon

My Son at 7 Years Old, by Suzanne Valadon Self-Portrait, 1893, by Suzanne Valadon

Self-Portrait, 1893, by Suzanne Valadon Nude, 1895, by Suzanne Valadon

Nude, 1895, by Suzanne Valadon Portrait of Erik Satie, 1893, by Suzanne Valadon

Portrait of Erik Satie, 1893, by Suzanne Valadon The Bath, 1908, by Suzanne Valadon

The Bath, 1908, by Suzanne Valadon Nudes, 1919, by Suzanne Valadon

Nudes, 1919, by Suzanne Valadon Flowers on a Round Table, 1920, by Suzanne Valadon

Flowers on a Round Table, 1920, by Suzanne Valadon Portrait of Maurice Utrillo, by Suzanne Valadon

Portrait of Maurice Utrillo, by Suzanne Valadon Portrait of the Painter Maurice Utrillo, 1921, by Suzanne Valadon

Portrait of the Painter Maurice Utrillo, 1921, by Suzanne Valadon Still Life with Tulips and Fruit Bowl, 1924, by Suzanne Valadon

Still Life with Tulips and Fruit Bowl, 1924, by Suzanne Valadon Bouquet of Flowers, 1928, by Suzanne Valadon

Bouquet of Flowers, 1928, by Suzanne Valadon Still Life with Basket of Apples Vase of Flowers, 1928, by Suzanne Valadon

Still Life with Basket of Apples Vase of Flowers, 1928, by Suzanne Valadon- Young Girl in Front of a Window, 1930, by Suzanne Valadon

Portraits of Valadon

The Hangover (Suzanne Valadon), by Toulouse-Lautrec.

The Hangover (Suzanne Valadon), by Toulouse-Lautrec. Profile portrait of Suzanne Valadon, by Renoir.

Profile portrait of Suzanne Valadon, by Renoir._-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Portrait of Suzanne Valadon, by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Portrait of Suzanne Valadon, by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Illustrations

- Jean Cocteau, Bertrand Guégan (1892-1943); L'almanach de Cocagne pour l'an 1920-1922, Dédié aux vrais Gourmands Et aux Francs Buveurs[39]

See also

- Musée de Montmartre, established in the building in which Valadon had an apartment and studio.

Notes

- 1 2 Warnod 40

- 1 2 3 4 Marchesseau 9

- 1 2 Marchesseau 15

- 1 2 Warnod 48

- ↑ "Suzanne Valadon". Akademiska Föreningen, Lund University. Archived from the original on 3 October 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 Marchesseau 16

- ↑ Marchesseau 17-18

- 1 2 3 Oxford Art Online

- 1 2 Jimenez, Jill Berk (2001). Dictionary of Artist's Models. London: Routledge. p. 529.

- 1 2 3 Mathews, Patricia (1991). "Returning the Gaze: Diverse Representations of the Nude in the Art of Suzanne Valadon". The Art Bulletin. 73.

- ↑ Warnod 13

- ↑ Warnod, Jeanine (1981). Suzanne Valadon. New York: Crown Publishers, INC. p. 13.

- ↑ "Suzanne Valadon". National Museum of Women in the Arts. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

- ↑ Rose 9

- ↑ Marchesseau 14

- ↑ Iskin, Ruth (2004). "The Nude in French Art and Culture". CAA. Reviews.

- ↑ Smee, Sebastian. "At MFA, dancing the night away in the arms of Renoir". The Boston Globe. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec". Harvard Art Museums. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Valadon, Suzanne"

- ↑ Burns, Janet M.C. Looking as Women: The Painting of Suzanne Valadon, Paula Modersohn-Becker and Frida Kahlo, Atlantis 1993: 18(1&2): 25-46.

- ↑ Betterton, Rosemary (Spring 1985). "How Do Women Look? The Female Nude in the Work of Suzanne Valadon". Feminist Review. 19: 3–24 [4]. doi:10.1057/fr.1985.2.

- ↑ Dolan, Threse (2001). "Passionate Discontent: Creativity, Gender and French Symbolist Art". CAA. Reviews.

- ↑ Warnod 8

- ↑ Warnod 48, 57

- ↑ Rose 97

- ↑ "Suzanne Valadon". Brooklyn Museum of Art. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

- ↑ Warnod 51

- ↑ Warnod 55

- 1 2 Marchesseau 17

- ↑ Marchesseau 18-19

- ↑ Marchesseau 9, 11

- ↑ "Suzanne Valadon". Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ↑ Mathews 415

- ↑ Mathews 418

- ↑ Mathews 416, 419, 423

- ↑ Warnod 88

- ↑

- ↑ The Razor's Edge by W. S. Maugham

- ↑ Notice WorldCat; sudoc; BnF. Engraved on wood and unpublished drawings of: Matisse, J. Marchand, R. Dufy, Sonia Lewitska, de Segonzac, Jean Émile Laboureur, Friesz, Marquet, Pierre Laprade, Signac, Louis Latapie, Suzanne Valadon, Henriette Tirman and others.´

References

- Burns, Janet M.C. (1993). "Looking as Women: The Paintings of Suzanne Valadon, Paula Modersohn-Becker and Frida Kahlo". Atlalntis. 18 (1&2): 25–46.

- Birnbaum, Paula J. Women Artists in Interwar France: Framing Femininities. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2011. Print.

- Giraudon, Colette. "Valadon, Suzanne." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 24 Sep. 2014. Online http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T087579

- Marchesseau, Daniel. Suzanne Valadon, exhibition catalogue, Martigny, Fondation Pierre Gianadda, 1996

- Mathews, Patricia (1991). "Returning the Gaze: Diverse Representations of the Nude in the Art of Suzanne Valadon". Art Bulletin. 73 (3): 415–30. doi:10.2307/3045814.

- Rose, June. Suzanne Valadon: The Mistress of Montmartre. New York: St. Martin's, 1999. ISBN 0-312-19921-X

- Storm, John. The Valadon Drama. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1958. Online https://archive.org/details/valadondramathel027482mbp

- Warnod, Jeanine. Suzanne Valadon. New York: Crown, 1981. Print.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Suzanne Valadon. |