Sustainable consumption

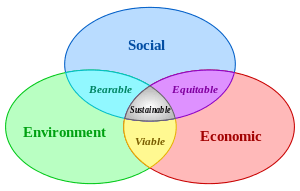

Sustainable consumption (SC) shares a number of common features with and is closely linked to the terms sustainable production and sustainable development. Sustainable consumption as part of sustainable development is a prerequisite in the worldwide struggle against sustainability challenges such as climate change, famines or environmental pollution.

Sustainable development as well as sustainable consumption rely on certain premises such as

- Wise use of resources, and minimisation of waste and pollution;

- Use of renewable resources within their capacity for renewal;

- Fuller product life-cycles; and

- Intergenerational and intragenerational equity

The Oslo definition

The definition proposed by the 1994 Oslo Symposium on Sustainable Consumption defines it as "the use of services and related products which respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life while minimizing the use of natural resources and toxic materials as well as emissions of waste and pollutants over the life cycle of the service or product so as not to jeopardize the needs of future generations."[1]

Strong and weak sustainable consumption

In order to achieve sustainable consumption, two developments have to take place: it requires both an increase in the efficiency of consumption as well as a change in consumption patterns and reductions in consumption levels in industrialized countries. The first prerequisite is not sufficient on its own and can be named weak sustainable consumption. Here, technological improvements and eco-efficiency support a necessary reduction in resource consumption. Once this aim has been met, the second prerequisite, the change in patterns and reduction of levels of consumption is indispensable. Strong sustainable consumption approaches also pay attention to the social dimension of well-being and assess the need for changes based on a risk-averse perspective.[2] In order to achieve what can be termed strong sustainable consumption, changes in infrastructures as well as the choices customers have are required. In the political arena, weak sustainable consumption has been discussed whereas strong sustainable consumption is missing from all debates.[3]

Taking into consideration those two approaches to sustainable consumption, it is evident that individual consumers play a key role. A huge problem is the existence of a so-called attitude-behaviour or values-action gap, i.e. many consumers are well aware of the importance of their consumption choices and care about environmental issues, however, most of them do not translate their concerns into their consumption patterns as the purchase-decision making process is highly complicated and relies on e.g. social, political and psychological factors. Young et al. identified a lack of time for research, high prices, a lack of information and the cognitive effort needed as the main barriers when it comes to green consumption choices.[4]

Institutionalising sustainable consumption

Developments of global sustainable consumption governance

- 1992 - At the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) the concept of sustainable consumption is established in chapter 4 of the Agenda 21.[5]

- 1994 - Sustainable Consumption Symposium in Oslo

- 1995 – SC was requested to be incorporated by UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) into the UN Guidelines on Consumer Protection.

- 1997 – A major report on SC was produced by the OECD [6]

- 1998 – United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) starts a SC program and SC is discussed in the Human Development Report of the UN Development Program (UNDP).[7]

- 2002 – Creation of a ten-year program on sustainable consumption and production (SCP) in the Plan of Implementation at the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in Johannesburg.[8]

- 2003 - The “Marrakech Process” was developed by co-ordination of a series of meetings and other “multi-stakeholder” processes by UNEP and UNDESA following the WSSD.[9]

Sustainable consumption initiatives

The Centre on Sustainable Consumption and Production is one of the leading independent authorities, that is exploring the dimensions of consumption and production. Another scientific network focusing on sustainable consumption research is the Sustainable Consumption Research and Action Initiative (SCORAI) with more than 800 members from mostly academia but also the non-profit sector.[10] In 2007, Tesco, the largest supermarket in the United Kingdom, established the Sustainable Consumption Institute (SCI) with a £25 million grant to The University of Manchester.

Sustainable consumption teaching

A benchmark of teaching activities on the topic of sustainable consumption has been carried out by the scientific network Sustainable Consumption Research and Action Initiative (SCORAI Europe) since 2015, with the support of the Swiss sd-universities program.[11] The review has lead to insights into courses being offered primarily in Europe, followed by North America, and Asia and the Pacific. Social change is emerging as a key theme, as well as the moral dimensions of economics and markets. A journal article is being developed to showcase the results of this study, which will include examples of transformative learning. Several resources to support sustainable consumption teaching are currently being developed, including a textbook by Lucie Middlemiss (Taylor and Francis).

See also

References

- ↑ Source: Norwegian Ministry of the Environment (1994) Oslo Roundtable on Sustainable Production and Consumption.

- ↑ Lorek, Sylvia; Fuchs, Doris (2013). "Strong Sustainable Consumption Governance - Precondition for a Degrowth Path?". Journal of Cleaner Production. 38: 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.08.008.

- ↑ Fuchs, Doris; Lorek, Sylvia (2005). "Sustainable Consumption Governance: A History of Promises and Failures". Journal of Consumer Policy. 28: 261–288. doi:10.1007/s10603-005-8490-z.

- ↑ Young, William (2010). "Sustainable Consumption: Green Consumer Behaviour when Purchasing Products". Sustainable Development (18): 20–31.

- ↑ United Nations. "Agenda 21" (PDF).

- ↑ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (1997) Sustainable Consumption and Production, Paris: OECD.

- ↑ United Nations Development Program (UNDP) (1998) Human Development Report, New York: UNDP.

- ↑ United Nations (UN) (2002) Plan of Implementation of the World Summit on Sustainable Development. In Report of the World Summit on Sustainable Development, UN Document A/CONF.199/20*, New York: UN.

- ↑ United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs (2010) Paving the Way to Sustainable Consumption and Production. In Marrakech Process Progress Report including Elements for a 10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production (SCP). [online] Available at: http://www.unep.fr/scp/marrakech/pdf/Marrakech%20Process%20Progress%20Report%20-%20Paving%20the%20Road%20to%20SCP.pdf [Accessed: 6/11/2011].

- ↑ "SCORAI Newsletter March 2016".

- ↑ "Benchmarking Overview". SCORAI. Retrieved 2016-03-04.