Pterygium (conjunctiva)

| Pterygium (conjunctiva) | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Surfer's eye[1] |

.jpg) | |

| Pterygium growing onto the cornea | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

| Symptoms | Pinkish, triangular tissue growth on the cornea[2] |

| Complications | Vision loss[2] |

| Usual onset | Gradual[2] |

| Causes | Unknown[2] |

| Risk factors | UV light, dust, genetics[2][3][4] |

| Similar conditions | Pinguecula, tumor, Terrien's marginal degeneration[5] |

| Prevention | Sunglasses, hat[2] |

| Treatment | None, eye lubricant, surgery[2] |

| Prognosis | Benign[6] |

| Frequency | 1% to 33%[7] |

A pterygium is a pinkish, triangular tissue growth on the cornea of the eye.[2] It typically starts on the cornea near the nose.[3] It may slowly grow but rarely grows so large that the pupil is covered.[2] Often both eyes are involved.[5]

The cause is unclear.[2] It appears to be partly related to long term exposure to UV light and dust.[2][3] Genetic factors also appear to be involved.[4] It is a benign growth.[6] Other conditions that can look similar include a pinguecula, tumor, or Terrien's marginal corneal degeneration.[5]

Prevention may include wearing sunglasses and a hat if in an area with strong sunlight. Among those with the condition, an eye lubricant can help with symptoms. Surgical removal is typically only recommended if the ability to see is affected.[2] Following surgery a pterygium may recur in around half of cases.[2][6]

The frequency of the condition varies from 1% to 33% in various regions of the world. It occurs more commonly among males than females and in people who live closer to the equator. The condition becomes more common with age.[7] The condition has been described since at least 1000 BC.[8]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of pterygium include persistent redness,[9] inflammation,[10] foreign body sensation, tearing, dry and itchy eyes. In advanced cases the pterygium can affect vision[10] as it invades the cornea with the potential of obscuring the optical center of the cornea and inducing astigmatism and corneal scarring.[11] Many patients do complain of the cosmetic appearance of the eye either with some of the symptoms above or as their major complaint.

Cause

The exact cause is unknown, but it is associated with excessive exposure to wind, sunlight, or sand. Therefore, it is more likely to occur in populations that inhabit the areas near the equator, as well as windy locations. In addition, pterygia are twice as likely to occur in men than women.

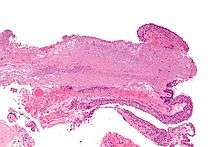

Pathology

Pterygium in the conjunctiva is characterized by elastotic degeneration of collagen (actinic elastosis[12]) and fibrovascular proliferation. It has an advancing portion called the head of the pterygium, which is connected to the main body of the pterygium by the neck. Sometimes a line of iron deposition can be seen adjacent to the head of the pterygium called Stocker's line. The location of the line can give an indication of the pattern of growth.

The predominance of pterygia on the nasal side is possibly a result of the sun's rays passing laterally through the cornea, where it undergoes refraction and becomes focused on the limbic area. Sunlight passes unobstructed from the lateral side of the eye, focusing on the medial limbus after passing through the cornea. On the contralateral (medial) side, however, the shadow of the nose medially reduces the intensity of sunlight focused on the lateral/temporal limbus.[9]

Some research also suggests a genetic predisposition due to an expression of vimentin, which indicates cellular migration by the keratoblasts embryological development, which are the cells that give rise to the layers of the cornea. Supporting this fact is the congenital pterygium, in which pterygium is seen in infants.[13] These cells also exhibit an increased P53 expression likely due to a deficit in the tumor suppressor gene. These indications give the impression of a migrating limbus because the cellular origin of the pterygium is actually initiated by the limbal epithelium.[14]

The pterygium is composed of several segments:

- Fuchs' Patches (minute gray blemishes that disperse near the pterygium head)

- Stocker's Line (a brownish line composed of iron deposits)

- Hood (fibrous nonvascular portion of the pterygium)

- Head (apex of the pterygium, typically raised and highly vascular)

- Body (fleshy elevated portion congested with tortuous vessels)

- Superior Edge (upper edge of the triangular or wing-shaped portion of the pterygium)

- Inferior Edge (lower edge of the triangular or wing-shaped portion of the pterygium).

Diagnosis

Pterygium (conjunctiva) can be diagnosed without need for a specific exam, however corneal topography is a practical test (technique) as the condition worsens.[15][16]

Prevention

As it is associated with excessive sun [17] or wind exposure, wearing protective sunglasses with side shields and/or wide brimmed hats and using artificial tears throughout the day may help prevent their formation or stop further growth. Surfers and other water-sport athletes should wear eye protection that blocks 100% of the UV rays from the water, as is often used by snow-sport athletes. Many of those who are at greatest risk of pterygium from work or play sun exposure do not understand the importance of protection.[18][19]

Treatment

Pterygium typically do not require surgery unless it grows to such an extent that it causes visual problems.[2] Some of the symptoms such as irritation can be addressed with artificial tears.[2] Surgery may also be considered for unmanageable symptoms.[20]

Surgery

A Cochrane review found conjunctival autograft surgery was less likely to have reoccurrence of the pterygium at 6 months compared to amniotic membrane transplant.[21] More research is needed to determine which type of surgery resulted in better vision or quality of life.[21] The additional use of mitomycin C is of unclear effect.[21] Radiotherapy has also be used in an attempt to reduce the risk of recurrence.[22]

Auto-grafting

Conjunctival auto-grafting is a surgical technique that is an effective and safe procedure for pterygium removal. When the pterygium is removed, the tissue that covers the sclera known as the Tenons layer is also removed. Auto-grafting covers the bare sclera with conjunctival tissue that is surgically removed from an area of healthy conjunctiva. That “self-tissue” is then transplanted to the bare sclera and is fixated using sutures or tissue adhesive.

Amniotic membrane transplantation

Amniotic membrane transplantation is an effective and safe procedure for pterygium removal. Amniotic membrane transplantation offers practical alternative to conjunctival auto graft transplantation for extensive pterygium removal. Amniotic membrane transplantation is tissue that is acquired from the innermost layer of the human placenta and has been used to replace and heal damaged mucosal surfaces including successful reconstruction of the ocular surface. It has been used as a surgical material since the 1940s, and has been shown to have a strong anti-adhesive effect.

Using an amniotic graft facilitates epithelialization, and has anti-inflammatory as well as surface rejuvenation properties. Amniotic membrane transplantation can also be fixated to the sclera using sutures, or glue adhesive.[23][24][25] Amniotic membrane by itself does not provide an acceptable recurrence rate.[26]

References

- ↑ Tollefsbol, Trygve (2016). Medical Epigenetics. Academic Press. p. 395. ISBN 9780128032404.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Facts About the Cornea and Corneal Disease | National Eye Institute". The National Eye Institute (NEI). May 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 Yanoff, Myron; Duker, Jay S. (2009). Ophthalmology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 364. ISBN 0323043321.

- 1 2 Anguria, P; Kitinya, J; Ntuli, S; Carmichael, T (2014). "The role of heredity in pterygium development.". International journal of ophthalmology. 7 (3): 563–73. PMC 4067677

. PMID 24967209. doi:10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2014.03.31.

. PMID 24967209. doi:10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2014.03.31. - 1 2 3 Smolin, Gilbert; Foster, Charles Stephen; Azar, Dimitri T.; Dohlman, Claes H. (2005). Smolin and Thoft's The Cornea: Scientific Foundations and Clinical Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1003, 1005. ISBN 9780781742061.

- 1 2 3 Halperin, Edward C.; Perez, Carlos A.; Brady, Luther W. (2008). Perez and Brady's Principles and Practice of Radiation Oncology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 778. ISBN 9780781763691.

- 1 2 Droutsas, K; Sekundo, W (June 2010). "[Epidemiology of pterygium. A review].". Der Ophthalmologe : Zeitschrift der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft (in German). 107 (6): 511–2, 514–6. PMID 20393731. doi:10.1007/s00347-009-2101-3.

- ↑ Saw, SM; Tan, D (September 1999). "Pterygium: prevalence, demography and risk factors.". Ophthalmic epidemiology. 6 (3): 219–28. PMID 10487976. doi:10.1076/opep.6.3.219.1504.

- 1 2 Coroneo, MT (November 1993). "Pterygium as an early indicator of ultraviolet insolation: a hypothesis". Br J Ophthalmol. 77 (11): 734–9. PMC 504636

. PMID 8280691. doi:10.1136/bjo.77.11.734.

. PMID 8280691. doi:10.1136/bjo.77.11.734. - 1 2 Kunimoto, Derek; Kunal Kanitkar; Mary Makar (2004). The Wills eye manual: office and emergency room diagnosis and treatment of eye disease. (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0781742078.

- ↑ Fisher, J.P.; Trattler, W.B. (12 January 2009). "Pterygium".

- ↑ Klintworth, G; Cummings, T. "24; The eye and ocular adnexa". In Stacey, Mills. Sternberg's Diagnostic Surgical Pathology (5th ed.). ISBN 978-0-7817-7942-5.

- ↑ http://www.paramountbooks.com.pk/LoginIndex.asp?title=Concise-Ophthalmology-(pb)-2014&Isbn=9789696370017&opt=3&sUBcAT=06

- ↑ Gulani, A; Dastur, YK (Jan–Mar 1995). "Simultaneous pterygium and cataract surgery.". Journal of postgraduate medicine. 41 (1): 8–11. PMID 10740692. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ↑ "Pterygium: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ↑ "Pterygium Workup: Imaging Studies, Procedures". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ↑ Mackenzie F.D., Hirst L.W., Battistutta D., Green A. (1992). "Risk Analysis in the Development of Pterygia". Ophthalmology. 99 (7): 1056–1061. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31850-0.

- ↑ Lee G.A., Hirst L.W., Sheehan M. "1994 Knowledge of Sunlight Effects on the Eyes and Protective Behaviours in the General Community. Ophthalmic Epidemiology". Ophthalmic Epidemiology. 1 (2): 67–84.

- ↑ Lee G., Hirst L.W., Sheehan M. "1999 Knowledge of Sunlight effects on the eyes and protective behaviors in adolescents". Ophthalmic Epidemiology. 6 (3): 171–180. doi:10.1076/opep.6.3.171.1501.

- ↑ Martins, TG; Costa, AL; Alves, MR; Chammas, R; Schor, P (2016). "Mitomycin C in pterygium treatment.". International journal of ophthalmology. 9 (3): 465–8. PMC 4844053

. PMID 27158622. doi:10.18240/ijo.2016.03.25.

. PMID 27158622. doi:10.18240/ijo.2016.03.25. - 1 2 3 Clearfield E, Muthappan V, Wang X, Kuo IC (2016). "Cojunctival autograft for pterygium". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2: CD011349. PMID 26867004. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011349.pub2.

- ↑ Ali, AM; Thariat, J; Bensadoun, RJ; Thyss, A; Rostom, Y; El-Haddad, S; Gérard, JP (April 2011). "The role of radiotherapy in the treatment of pterygium: a review of the literature including more than 6000 treated lesions.". Cancer radiotherapie : journal de la Societe francaise de radiotherapie oncologique. 15 (2): 140–7. PMID 20674450. doi:10.1016/j.canrad.2010.03.020.

- ↑ Gulani AC (2007). "Corneoplastique". Techniques in Ophthalmology. 5 (1): 11–20. doi:10.1097/ito.0b013e318036ae0d.

- ↑ Gulani AC. "Corneoplastique", Video Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery. Volume XXII. Issue 3, 2006.

- ↑ Gulani AC (2006). "A New Concept for Refractive Surgery". Ophthalmology Management. 10 (4): 57–63.

- ↑ Ophthalmology. 1997 Jun;104(6):974-85.Comparison of conjunctival autografts, amniotic membrane grafts, and primary closure for pterygium excision. Prabhasawat P1, Barton K, Burkett G, Tseng SC

External links

Media related to pterygium at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to pterygium at Wikimedia Commons

| Classification |

V · T · D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pterygium eMedicine WebMD online article on pterygium (overview, differential diagnoses & workup, treatment & medication, and follow-up)