Supernatural

The supernatural (Medieval Latin: supernātūrālis: supra "above" + naturalis "natural", first used: 1520–1530 AD)[1][2] includes all that cannot be explained by the laws of nature, including things characteristic of or relating to ghosts, gods, or other types of spirits and other non-material beings, or to things beyond nature.[3]

Views

The metaphysical considerations of the existence of the supernatural can be difficult to approach as an exercise in philosophy or theology because any dependencies on its antithesis, the natural, will ultimately have to be inverted or rejected.

One complicating factor is that there is disagreement about the definition of "natural" and the limits of naturalism. Concepts in the supernatural domain are closely related to concepts in religious spirituality and occultism or spiritualism.

For sometimes we use the word nature for that Author of nature whom the schoolmen, harshly enough, call natura naturans, as when it is said that nature hath made man partly corporeal and partly immaterial. Sometimes we mean by the nature of a thing the essence, or that which the schoolmen scruple not to call the quiddity of a thing, namely, the attribute or attributes on whose score it is what it is, whether the thing be corporeal or not, as when we attempt to define the nature of an angle, or of a triangle, or of a fluid body, as such. Sometimes we take nature for an internal principle of motion, as when we say that a stone let fall in the air is by nature carried towards the centre of the earth, and, on the contrary, that fire or flame does naturally move upwards toward heaven. Sometimes we understand by nature the established course of things, as when we say that nature makes the night succeed the day, nature hath made respiration necessary to the life of men. Sometimes we take nature for an aggregate of powers belonging to a body, especially a living one, as when physicians say that nature is strong or weak or spent, or that in such or such diseases nature left to herself will do the cure. Sometimes we take nature for the universe, or system of the corporeal works of God, as when it is said of a phoenix, or a chimera, that there is no such thing in nature, i.e. in the world. And sometimes too, and that most commonly, we would express by nature a semi-deity or other strange kind of being, such as this discourse examines the notion of.

And besides these more absolute acceptions, if I may so call them, of the word nature, it has divers others (more relative), as nature is wont to be set or in opposition or contradistinction to other things, as when we say of a stone when it falls downwards that it does it by a natural motion, but that if it be thrown upwards its motion that way is violent. So chemists distinguish vitriol into natural and fictitious, or made by art, i.e. by the intervention of human power or skill; so it is said that water, kept suspended in a sucking pump, is not in its natural place, as that is which is stagnant in the well. We say also that wicked men are still in the state of nature, but the regenerate in a state of grace; that cures wrought by medicines are natural operations; but the miraculous ones wrought by Christ and his apostles were supernatural.[4]— Robert Boyle, A Free Enquiry into the Vulgarly Received Notion of Nature

The term "supernatural" is often used interchangeably with paranormal or preternatural — the latter typically limited to an adjective for describing abilities which appear to exceed the bounds of possibility.[5] Epistemologically, the relationship between the supernatural and the natural is indistinct in terms of natural phenomena that, ex hypothesi, violate the laws of nature, in so far as such laws are realistically accountable.

Parapsychologists use the term psi to refer to an assumed unitary force underlying the phenomena they study. Psi is defined in the Journal of Parapsychology as “personal factors or processes in nature which transcend accepted laws” (1948: 311) and “which are non-physical in nature” (1962:310), and it is used to cover both extrasensory perception (ESP), an “awareness of or response to an external event or influence not apprehended by sensory means” (1962:309) or inferred from sensory knowledge, and psychokinesis (PK), “the direct influence exerted on a physical system by a subject without any known intermediate energy or instrumentation” (1945:305).[6]— Michael Winkelman, Current Anthropology

Many supporters of supernatural explanations believe that past, present, and future complexities and mysteries of the universe cannot be explained solely by naturalistic means and argue that it is reasonable to assume that a non-natural entity or entities resolve the unexplained.

Views on the "supernatural" vary, for example it may be seen as:

- indistinct from nature. From this perspective, some events occur according to the laws of nature, and others occur according to a separate set of principles external to known nature. For example, in Scholasticism, it was believed that God was capable of performing any miracle so long as it didn't lead to a logical contradiction. Some religions posit immanent deities, however, and do not have a tradition analogous to the supernatural; some believe that everything anyone experiences occurs by the will (occasionalism), in the mind (neoplatonism), or as a part (nondualism) of a more fundamental divine reality (platonism).

- incorrectly attributed to nature. Others believe that all events have natural and only natural causes. They believe that human beings ascribe supernatural attributes to purely natural events, such as lightning, rainbows, floods, and the origin of life.[7][8]

Philosophy

The supernatural is a feature of the philosophical traditions of Neoplatonism[9] and Scholasticism.[10] In contrast, the philosophy of Metaphysical naturalism argues for the conclusion that there are no supernatural entities, objects, or powers.

Religion

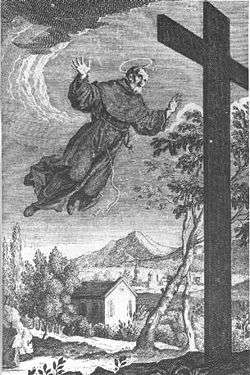

Most religions include elements of belief in the supernatural (e.g. miraculous works by recognized Saints, the Assumption of Mary, etc.) while also often featuring prominently in the study of the paranormal and occultism.

Christian theology

In Catholic theology, the supernatural order is, according to New Advent, defined as "the ensemble of effects exceeding the powers of the created universe and gratuitously produced by God for the purpose of raising the rational creature above its native sphere to a God-like life and destiny."[12] The Modern Catholic Dictionary defines it as "[t]he sum total of heavenly destiny and all the divinely established means of reaching that destiny, which surpass the mere powers and capacities of human nature."[13]

Process theology

Process theology is a school of thought influenced by the metaphysical process philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947) and further developed by Charles Hartshorne (1897–2000).

It is not possible, in process metaphysics, to conceive divine activity as a “supernatural” intervention into the “natural” order of events. Process theists usually regard the distinction between the supernatural and the natural as a by-product of the doctrine of creation ex nihilo. In process thought, there is no such thing as a realm of the natural in contrast to that which is supernatural. On the other hand, if “the natural” is defined more neutrally as “what is in the nature of things,” then process metaphysics characterizes the natural as the creative activity of actual entities. In Whitehead's words, “It lies in the nature of things that the many enter into complex unity” (Whitehead 1978, 21). It is tempting to emphasize process theism's denial of the supernatural and thereby highlight what the process God cannot do in comparison to what the traditional God can do (that is, to bring something from nothing). In fairness, however, equal stress should be placed on process theism's denial of the natural (as traditionally conceived) so that one may highlight what the creatures cannot do, in traditional theism, in comparison to what they can do in process metaphysics (that is, to be part creators of the world with God).[14]— Donald Viney, "Process Theism" in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

See also

| Look up supernatural in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Supernatural |

- Magical thinking

- Metaphysical naturalism

- Non-physical entity

- Preternatural

- Religious naturalism

- Supernaturalism

References

- ↑ "Supernatural | Define Supernatural at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2013-06-30.

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2013-06-30.

- ↑ "Supernatural | Define Supernatural at Merriam-Webster.com".

- ↑ Boyle, Robert; Stewart, M.A. (1991). Selected Philosophical Papers of Robert Boyle. HPC Classics Series. Hackett. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-0-87220-122-4. LCCN 91025480.

- ↑ The paranormal. Books.google.com. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ↑ Winkelman, M.; et al. (February 1982). "Magic: A Theoretical Reassessment [and Comments and Replies]". Current Anthropology. 23 (1): 37–66. JSTOR 274255. doi:10.1086/202778.

- ↑ Zhong Yang Yan Jiu Yuan; Min Tsu Hsüeh Yen Chiu So (1976). Bulletin of the Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica, Issues 42–44.

- ↑ Ellis, B.J.; Bjorklund, D.F. (2004). Origins of the Social Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and Child Development. Guilford Publications. p. 413. ISBN 9781593851033. LCCN 2004022693.

- ↑ "The eventual development of a clear concept of the supernatural in Christian theology was promoted both by dialogues with heretics and by the influence of Neoplatonic philosophy." Benson Saler: Supernatural as a Western Category. Ethos 5 (1977): 44

- ↑ "Saint Thomas's important contribution to the emergence of a technical theology of the supernatural represents a special development of the concept of surpassing effects. Saint Thomas and others of the Scholastics have left us as one of their legacies a dichotomy between the natural and the supernatural that is theologically rooted in the distinction between the Order of Nature and the Order of Grace." Benson Saler: Supernatural as a Western Category. Ethos 5 (1977): 47–48

- ↑ Pastrovicchi, Angelo (1918). Rev. Francis S. Laing, ed. St. Joseph of Copertino. St. Louis: B.Herder. p. iv. ISBN 0-89555-135-7.

- ↑ Sollier, J. "Supernatural Order". Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ↑ Hardon, Fr. John. "Supernatural Order". Eternal Life. Retrieved 2008-09-15.

- ↑ Viney, Donald (2008). Edward N. Zalta, ed. "Process Theism". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2008 ed.).

Further reading

- Bouvet R, Bonnefon J. F. (2015). "Non-Reflective Thinkers Are Predisposed to Attribute Supernatural Causation to Uncanny Experiences". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 41: 955–61. PMID 25948700. doi:10.1177/0146167215585728.

- McNamara P, Bulkeley K (2015). "Dreams as a Source of Supernatural Agent Concepts". Frontiers in Psychology. 6: 283. PMC 4365543

. PMID 25852602. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00283.

. PMID 25852602. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00283. - Riekki T, Lindeman M, Raij T. T. (2014). "Supernatural Believers Attribute More Intentions to Random Movement than Skeptics: An fMRI Study". Social Neuroscience. 9: 400–411. doi:10.1080/17470919.2014.906366.

- Purzycki Benjamin G (2013). "The Minds of Gods: A Comparative Study of Supernatural Agency". Cognition. 129: 163–179. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2013.06.010.

- Thomson P, Jaque S. V. (2014). "Unresolved Mourning, Supernatural Beliefs and Dissociation: A Mediation Analysis". Attachment and Human Development. 16: 499–514. doi:10.1080/14616734.2014.926945.

- Vail K. E, Arndt J, Addollahi A. (2012). "Exploring the Existential Function of Religion and Supernatural Agent Beliefs Among Christians, Muslims, Atheists, and Agnostics". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 38: 1288–1300. doi:10.1177/0146167212449361.