Airbus A380

| A380 | |

|---|---|

_(cropped).jpg) | |

| Emirates is the largest operator of the A380. | |

| Role | Wide-body, double-deck jet airliner |

| National origin | Multi-national[1] |

| Manufacturer | Airbus |

| First flight | 27 April 2005 |

| Introduction | 25 October 2007 with Singapore Airlines |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Emirates Singapore Airlines Lufthansa |

| Produced | 2005–present |

| Number built | 214 as of 31 July 2017[2] |

| Program cost | €15 billion (Airbus 2015)[3] to €25 billion (2016 estimate)[4] |

| Unit cost | |

The Airbus A380 is a double-deck, wide-body, four-engine jet airliner manufactured by European manufacturer Airbus.[6][7] It is the world's largest passenger airliner, and the airports at which it operates have upgraded facilities to accommodate it. It was initially named Airbus A3XX and designed to challenge Boeing's monopoly in the large-aircraft market. The A380 made its first flight on 27 April 2005 and entered commercial service on 25 October 2007 with Singapore Airlines. An improved version, the A380plus, is under development.

The A380's upper deck extends along the entire length of the fuselage, with a width equivalent to a wide-body aircraft. This gives the A380-800's cabin 550 square metres (5,920 sq ft) of usable floor space,[8] 40% more than the next largest airliner, the Boeing 747-8,[9] and provides seating for 525 people in a typical three-class configuration or up to 853 people in an all-economy class configuration. The A380-800 has a design range of 8,500 nautical miles (15,700 km), serving the second- and third-longest non-stop scheduled flights in the world (as of February 2017), and a cruising speed of Mach 0.85 (about 900 km/h, 560 mph or 490 kt at cruising altitude).

As of July 2017, Airbus had received 317 firm orders and delivered 214 aircraft; Emirates is the biggest A380 customer with 142 ordered of which 96 have been delivered.[2]

Development

Background

In mid-1988, Airbus engineers led by Jean Roeder began work in secret on the development of an ultra-high-capacity airliner (UHCA), both to complete its own range of products and to break the dominance that Boeing had enjoyed in this market segment since the early 1970s with its 747.[10] McDonnell Douglas unsuccessfully offered its smaller, double-deck MD-12 concept for sale.[11][12] Roeder was given approval for further evaluations of the UHCA after a formal presentation to the President and CEO in June 1990. The megaproject was announced at the 1990 Farnborough Air Show, with the stated goal of 15% lower operating costs than the 747-400.[13] Airbus organised four teams of designers, one from each of its partners (Aérospatiale, British Aerospace, Deutsche Aerospace AG, CASA) to propose new technologies for its future aircraft designs. The designs were presented in 1992 and the most competitive designs were used.[14]

In January 1993, Boeing and several companies in the Airbus consortium started a joint feasibility study of a Very Large Commercial Transport (VLCT), aiming to form a partnership to share the limited market.[15][16] This joint study was abandoned two years later, Boeing's interest having declined because analysts thought that such a product was unlikely to cover the projected $15 billion development cost. Despite the fact that only two airlines had expressed public interest in purchasing such a plane, Airbus was already pursuing its own large-plane project. Analysts suggested that Boeing would instead pursue stretching its 747 design, and that air travel was already moving away from the hub-and-spoke system that consolidated traffic into large planes, and toward more non-stop routes that could be served by smaller planes.[17]

In June 1994, Airbus announced its plan to develop its own very large airliner, designated as A3XX.[18][19] Airbus considered several designs, including an unusual side-by-side combination of two fuselages from its A340, the largest Airbus jet at the time.[20] The A3XX was pitted against the VLCT study and Boeing's own New Large Aircraft successor to the 747.[21][22] From 1997 to 2000, as the East Asian financial crisis darkened the market outlook, Airbus refined its design, targeting a 15–20% reduction in operating costs over the existing Boeing 747–400. The A3XX design converged on a double-decker layout that provided more passenger volume than a traditional single-deck design,[23][24] in line with traditional hub-and-spoke theory as opposed to the point-to-point theory with the Boeing 777,[25] after conducting an extensive market analysis with over 200 focus groups.[26][27] Although early marketing of the huge cross-section touted the possibility of duty-free shops, restaurant-like dining, gyms, casinos and beauty parlours on board, the realities of airline economics have kept such dreams grounded.

On 19 December 2000, the supervisory board of newly restructured Airbus voted to launch an €8.8-billion programme to build the A3XX, re-christened as the A380,[28][29] with 50 firm orders from six launch customers.[30][31] The A380 designation was a break from previous Airbus families, which had progressed sequentially from A300 to A340. It was chosen because the number 8 resembles the double-deck cross section, and is a lucky number in some Asian countries where the aircraft was being marketed.[20] The aircraft configuration was finalised in early 2001, and manufacturing of the first A380 wing-box component started on 23 January 2002. The development cost of the A380 had grown to €11–14[32] billion when the first aircraft was completed.

Total development cost

In 2000, the originally projected development cost was €9.5 billion.[33] In 2004 Airbus estimated 1.5 billion euros ($2 billion) would be added for a €10.3 Bn ($12.7 Bn) total.[34] In 2006 at €10.2 Billion, Airbus stopped publishing its reported cost and then provisioned €4.9 Bn after the difficulties in electric cabling and two years delay for an estimated total of €18 Bn.[33]

In 2014, the aircraft was estimated to have cost $25bn (£16bn – €18.9bn) to develop.[35] In 2015, Airbus said development costs were €15bn (£11.4bn – $16.95 Bn), though analysts believe the figure is likely to be at least €5bn ($5.65 Bn) more for a €20 Bn ($22.6 Bn) total.[3] In 2016, The A380 development costs were estimated at $25 billion for 15 years,[36] $25–30 billion,[37] or 25 billion euros ($28 billion).[4]

Production

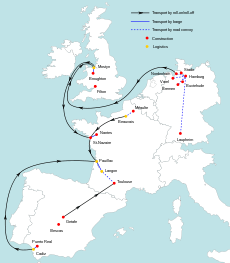

Major structural sections of the A380 are built in France, Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Due to the sections' large size, traditional transportation methods proved unfeasible,[38] so they are brought to the Jean-Luc Lagardère Plant assembly hall in Toulouse, France, by specialised road and water transportation, though some parts are moved by the A300-600ST Beluga transport aircraft.[39][40] A380 components are provided by suppliers from around the world; the four largest contributors, by value, are Rolls-Royce, Safran, United Technologies and General Electric.[26]

For the surface movement of large A380 structural components, a complex route known as the Itinéraire à Grand Gabarit was developed. This involved the construction of a fleet of roll-on/roll-off (RORO) ships and barges, the construction of port facilities and the development of new and modified roads to accommodate oversized road convoys.[41] The front and rear fuselage sections are shipped on one of three RORO ships from Hamburg in northern Germany to the United Kingdom.[42] The wings are manufactured at Broughton in North Wales, then transported by barge to Mostyn docks for ship transport.[43]

In Saint-Nazaire in western France, the ship exchanges the fuselage sections from Hamburg for larger, assembled sections, some of which include the nose. The ship unloads in Bordeaux. The ship then picks up the belly and tail sections from Construcciones Aeronáuticas SA in Cádiz in southern Spain, and delivers them to Bordeaux. From there, the A380 parts are transported by barge to Langon, and by oversize road convoys to the assembly hall in Toulouse.[44] In order to avoid damage from direct handling, parts are secured in custom jigs carried on self-powered wheeled vehicles.[38]

After assembly, the aircraft are flown to Hamburg Finkenwerder Airport (XFW) to be furnished and painted. Airbus sized the production facilities and supply chain for a production rate of four A380s per month.[43]

Testing

Five A380s were built for testing and demonstration purposes.[45] The first A380, registered F-WWOW, was unveiled in Toulouse 18 January 2005.[46] It first flew on 27 April 2005.[47] This plane, equipped with Rolls-Royce Trent 900 engines, flew from Toulouse Blagnac International Airport with a crew of six headed by chief test pilot Jacques Rosay.[48] Rosay said flying the A380 had been "like handling a bicycle".[49]

On 1 December 2005, the A380 achieved its maximum design speed of Mach 0.96, (its design cruise speed is Mach 0.85) in a shallow dive.[45] In 2006, the A380 flew its first high-altitude test at Bole International Airport, Addis Ababa. It conducted its second high-altitude test at the same airport in 2009.[50] On 10 January 2006, it flew to José María Córdova International Airport in Colombia, accomplishing the transatlantic testing, and then it went to El Dorado International Airport to test the engine operation in high-altitude airports. It arrived in North America on 6 February 2006, landing in Iqaluit, Nunavut in Canada for cold-weather testing.[51]

On 14 February 2006, during the destructive wing strength certification test on MSN5000, the test wing of the A380 failed at 145% of the limit load, short of the required 150% level. Airbus announced modifications adding 30 kg (66 lb) to the wing to provide the required strength.[52] On 26 March 2006, the A380 underwent evacuation certification in Hamburg. With 8 of the 16 exits arbitrarily blocked, 853 mixed passengers and 20 crew exited the darkened aircraft in 78 seconds, less than the 90 seconds required for certification.[53][54] Three days later, the A380 received European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) and United States Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) approval to carry up to 853 passengers.[55]

The first A380 using GP7200 engines—serial number MSN009 and registration F-WWEA—flew on 25 August 2006.[56][57] On 4 September 2006, the first full passenger-carrying flight test took place.[58] The aircraft flew from Toulouse with 474 Airbus employees on board, in a test of passenger facilities and comfort.[58] In November 2006, a further series of route-proving flights demonstrated the aircraft's performance for 150 flight hours under typical airline operating conditions.[59] As of 2014, the A380 test aircraft continue to perform test procedures.[60]

Airbus obtained type certificates for the A380-841 and A380-842 model from the EASA and FAA on 12 December 2006 in a joint ceremony at the company's French headquarters,[61][62] receiving the ICAO code A388.[63] The A380-861 model obtained its type certificate on 14 December 2007.[62]

Production and delivery delays

.jpg)

Initial production of the A380 was troubled by delays attributed to the 530 km (330 mi) of wiring in each aircraft. Airbus cited as underlying causes the complexity of the cabin wiring (98,000 wires and 40,000 connectors), its concurrent design and production, the high degree of customisation for each airline, and failures of configuration management and change control.[64][65] The German and Spanish Airbus facilities continued to use CATIA version 4, while British and French sites migrated to version 5.[66] This caused overall configuration management problems, at least in part because wire harnesses manufactured using aluminium rather than copper conductors necessitated special design rules including non-standard dimensions and bend radii; these were not easily transferred between versions of the software.[67]

Airbus announced the first delay in June 2005 and notified airlines that deliveries would be delayed by six months.[66] This reduced the total number of planned deliveries by the end of 2009 from about 120 to 90–100. On 13 June 2006, Airbus announced a second delay, with the delivery schedule slipping an additional six to seven months.[68] Although the first delivery was still planned before the end of 2006, deliveries in 2007 would drop to only 9 aircraft, and deliveries by the end of 2009 would be cut to 70–80 aircraft. The announcement caused a 26% drop in the share price of Airbus' parent, EADS,[69] and led to the departure of EADS CEO Noël Forgeard, Airbus CEO Gustav Humbert, and A380 programme manager Charles Champion.[66][70] On 3 October 2006, upon completion of a review of the A380 programme, Airbus CEO Christian Streiff announced a third delay,[66] pushing the first delivery to October 2007, to be followed by 13 deliveries in 2008, 25 in 2009, and the full production rate of 45 aircraft per year in 2010.[71] The delay also increased the earnings shortfall projected by Airbus through 2010 to €4.8 billion.[66][72]

As Airbus prioritised the work on the A380-800 over the A380F,[73] freighter orders were cancelled by FedEx[74][75] and United Parcel Service,[76] or converted to A380-800 by Emirates and ILFC.[77] Airbus suspended work on the freighter version, but said it remained on offer,[78] albeit without a service entry date.[79] For the passenger version Airbus negotiated a revised delivery schedule and compensation with the 13 customers, all of which retained their orders with some placing subsequent orders, including Emirates,[80] Singapore Airlines,[81] Qantas,[82] Air France,[83] Qatar Airways,[84] and Korean Air.[85]

Beginning in 2007 the A380 was considered as a potential replacement for the existing Boeing VC-25 serving as Air Force One presidential transport,[86][87] but in January 2009 EADS declared that they were not going to bid for the contract, as assembling only three planes in the US would not make financial sense.[88]

On 13 May 2008, Airbus announced reduced deliveries for the years 2008 (12) and 2009 (21).[89] After further manufacturing setbacks, Airbus announced its plan to deliver 14 A380s in 2009, down from the previously revised target of 18.[90] A total of 10 A380s were delivered in 2009.[91] In 2010 Airbus delivered 18 of the expected 20 A380s, due to Rolls-Royce engine availability problems.[92] Airbus planned to deliver "between 20 and 25" A380s in 2011 before ramping up to three a month in 2012.[92] In fact, Airbus delivered 26 units, thus outdoing its predicted output for the first time. As of July 2012, production was 3 aircraft per month. Among the production problems are challenging interiors, interiors being installed sequentially rather than concurrently as in smaller planes, and union/government objections to streamlining.[93]

At the July 2016 Farnborough Airshow Airbus announced that in a “prudent, proactive step,” starting in 2018 it expects to deliver 12 A380 aircraft per year, down from 27 deliveries in 2015. The firm also warned production might slip back into red ink on each aircraft produced at that time, though it anticipates production will remain in the black for 2016 and 2017. “The company will continue to improve the efficiency of its industrial system to achieve breakeven at 20 aircraft in 2017 and targets additional cost reduction initiatives to lower breakeven further.”[94][95] Airbus expects that healthy demand for its other aircraft would allow it to avoid job losses from the cuts.[96][97]

As Airbus expects to build 15 airliners in 2017 and 12 in 2018, Airbus Commercial Aircraft president Fabrice Brégier said without orders in 2017 production should be reduced below one per month while remaining profitable per unit and have the program continue for 20 to 30 years.[98] Within its 2017 half-year report, Airbus adjusted 2019 deliveries to eight aircraft.[99]

Entry into service

Nicknamed Superjumbo,[100] the first A380, MSN003 (registered as 9V-SKA), was delivered to Singapore Airlines on 15 October 2007 and entered service on 25 October 2007 with flight number SQ380 between Singapore and Sydney.[16][101] Passengers bought seats in a charity online auction paying between $560 and $100,380.[102] Two months later, Singapore Airlines CEO Chew Choong Seng stated the A380 was performing better than either the airline and Airbus had anticipated, burning 20% less fuel per seat-mile than the airline's 747–400 fleet.[103] Emirates' Tim Clark claimed that the A380 has better fuel economy at Mach 0.86 than at 0.83,[104] and that its technical dispatch reliability is at 97%, same as Singapore Airlines. Airbus is committed to reach the industry standard of 98.5%.[105]

Emirates was the second airline to receive the A380 and commenced service between Dubai and New York in August 2008.[106][107] Qantas followed, with flights between Melbourne and Los Angeles in October 2008.[108] By the end of 2008, 890,000 passengers had flown on 2,200 flights.[109]

In February 2009, the one millionth passenger was flown with Singapore Airlines[110] and by May of that year 1,500,000 passengers had flown on 4,200 flights.[111] Air France received its first A380 in October 2009.[112][113] Lufthansa received its first A380 in May 2010.[114] By July 2010, the 31 A380s then in service had transported 6 million passengers on 17,000 flights between 20 international destinations.[115]

Airbus delivered the 100th A380 on 14 March 2013 to Malaysia Airlines.[116] In June 2014, over 65 million passengers had flown the A380,[117] and more than 100 million passengers (averaging 375 per flight) by September 2015, with an availability of 98.5%.[118] In 2014, Emirates stated that their A380 fleet had load factors of 90–100%, and that the popularity of the aircraft with its passengers had not decreased in the past year.[119]

Improvements and upgrades

In 2010, Airbus announced a new A380 build standard, incorporating a strengthened airframe structure and a 1.5° increase in wing twist. Airbus will also offer, as an option, an improved maximum take-off weight, thus providing a better payload/range performance. Maximum take-off weight is increased by 4 t (8,800 lb), to 573 t (1,263,000 lb) and the range is extended by 100 nautical miles (190 km); this is achieved by reducing flight loads, partly from optimising the fly-by-wire control laws.[120] British Airways and Emirates are the first two customers to have received this new option in 2013.[121] Emirates has asked for an update with new engines for the A380 to be competitive with the 777X around 2020, and Airbus is studying 11-abreast seating.[122]

In 2012, Airbus announced another increase in the A380's maximum take-off weight to 575 t (1,268,000 lb), a 6 t increase from the initial A380 variant and 2 t higher than the increased-weight proposal of 2010. Its range will increase by some 150 nautical miles (280 km), taking its capability to around 8,350 nautical miles (15,460 km) at current payloads. The higher-weight version was offered for introduction to service early in 2013.[123]

Post-delivery issues

During repairs following the Qantas Flight 32 engine failure incident, cracks were discovered in wing fittings. As a result, the European Aviation Safety Agency issued an Airworthiness Directive in January 2012 which affected 20 A380 aircraft that had accumulated over 1,300 flights.[124] A380s with under 1,800 flight hours were to be inspected within 6 weeks or 84 flights; aircraft with over 1,800 flight hours were to be examined within four days or 14 flights.[125][126][127] Fittings found to be cracked were replaced.[128] On 8 February 2012, the checks were extended to cover all 68 A380 aircraft in operation. The problem is considered to be minor and is not expected to affect operations.[129] EADS acknowledged that the cost of repairs would be over $130 million, to be borne by Airbus. The company said the problem was traced to stress and material used for the fittings.[130] Additionally, major airlines are seeking compensation from Airbus for revenue lost as a result of the cracks and subsequent grounding of fleets.[131] Airbus has switched to a different type of aluminium alloy so aircraft delivered from 2014 onwards should not have this issue.[132]

Airbus is changing about 10% of all doors, as some leak during flight. One occurrence resulted in dropped oxygen masks and an emergency landing. The switch is expected to cost over €100 million. Airbus states that safety is sufficient, as the air pressure pushes the door into the frame.[133][134][135]

Design

Overview

The A380 was initially offered in two models, the A380-800 and the A380F. The A380-800's original configuration carried 555 passengers in a three-class configuration[136] or 853 passengers (538 on the main deck and 315 on the upper deck) in a single-class economy configuration. Then in May 2007, Airbus began marketing a configuration with 30 fewer passengers (525 total in three classes)—traded for 200 nmi (370 km) more range—to better reflect trends in premium-class accommodation.[137] The design range for the −800 model is 8,500 nmi (15,700 km);[138] capable of flying from Hong Kong to New York or from Sydney to Istanbul non-stop. The second model, the A380F freighter, would carry 150 tonnes of cargo with a range of 5,600 nmi (10,400 km).[139] The freighter development was put on hold as Airbus prioritised the passenger version and all cargo orders were cancelled. Future variants may include an A380-900 stretch, seating about 656 passengers (or up to 960 passengers in an all-economy configuration), and an extended-range version with the same passenger capacity as the A380-800.[20]

Engines

The A380 is available with two types of turbofan engines, the Rolls-Royce Trent 900 (variants A380-841, −842 and −843F) or the Engine Alliance GP7000 (A380-861 and −863F). The Trent 900 is a derivative of the Trent 800, and the GP7000 has roots from the GE90 and PW4000. The Trent 900 core is a scaled version of the Trent 500, but incorporates the swept fan technology of the stillborn Trent 8104.[140] The GP7200 has a GE90-derived core and PW4090-derived fan and low-pressure turbo-machinery.[141] Noise reduction was an important requirement in the A380 design, and particularly affects engine design.[142][143] Both engine types allow the aircraft to achieve well under the QC/2 departure and QC/0.5 arrival noise limits under the Quota Count system set by Heathrow Airport,[144] which is a key destination for the A380.[20] The A380 has received an award for its reduced noise.[145] However, field measurements suggest the approach quota allocation for the A380 may be overly generous compared to the older Boeing 747, but still quieter.[146][147] Rolls-Royce is supporting CAA in understanding the relatively high A380/Trent 900 monitored noise levels.[148]

The A380 was initially planned without thrust reversers, incorporating sufficient braking capacity to do without them.[149] However Airbus elected to equip the two inboard engines with thrust reversers in a late stage of development,[150][151] helping the brakes when the runway is slippery. The two outboard engines do not have reversers, reducing the amount of debris stirred up during landing.[152] The A380 has electrically actuated thrust reversers, giving them better reliability than their pneumatic or hydraulic equivalents, in addition to saving weight.[153]

In 2008, the A380 demonstrated the viability of a synthetic fuel comprising standard jet fuel with a natural-gas-derived component. On 1 February 2008, a three-hour test flight operated between Britain and France, with one of the A380's four engines using a mix of 60% standard jet kerosene and 40% gas to liquids (GTL) fuel supplied by Shell.[154] The aircraft needed no modifications for the GTL fuel, which was designed to be mixed with normal jet fuel. Sebastien Remy, head of Airbus SAS's alternative fuel programme, said the GTL used was no cleaner in CO2 terms than standard fuel but contains no sulphur, generating air quality benefits.[155]

The auxiliary power comprises the Auxiliary Power Unit (APU), the electronic control box (ECB), and mounting hardware. The APU in use on the A380 is the PW 980A APU. The APU primarily provides air to power the Analysis Ground Station (AGS) on the ground and to start the engines. The AGS is a semi-automatic analysis system of flight data that helps to optimise management of maintenance and reduce costs. The APU also powers electric generators which provide auxiliary electric power to the aircraft.[156]

Wings

The A380's wing is sized for a maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) over 650 tonnes to accommodate these future versions, albeit with some internal strengthening required on the A380F freighter.[20][157] The optimal wingspan for this weight is about 90 m (300 ft), but airport restrictions limited it to less than 80 m (260 ft), lowering aspect ratio to 7.8 which reduces fuel efficiency[122] about 10% and increases operating costs a few percent,[158] given that fuel costs constitute about 50% of the cost of long-haul airplane operation.[159] The common wing design approach sacrifices fuel efficiency on the A380-800 passenger model because of its weight but Airbus estimates that the aircraft's size and advanced technology will provide lower operating costs per passenger than the 747-400. The wings incorporate wingtip fences that extend above and below the wing surface, similar to those on the A310 and A320. These increase fuel efficiency and range by reducing induced drag.[160] The wingtip fences also reduce wake turbulence, which endangers following aircraft and could, theoretically, damage house roofs.[161]

Materials

While most of the fuselage is made of aluminium alloys, composite materials comprise more than 20% of the A380's airframe.[162] Carbon-fibre reinforced plastic, glass-fibre reinforced plastic and quartz-fibre reinforced plastic are used extensively in wings, fuselage sections (such as the undercarriage and rear end of fuselage), tail surfaces, and doors.[163][164][165] The A380 is the first commercial airliner to have a central wing box made of carbon fibre reinforced plastic. It is also the first to have a smoothly contoured wing cross section. The wings of other commercial airliners are partitioned span-wise into sections. This flowing continuous cross section reduces aerodynamic drag. Thermoplastics are used in the leading edges of the slats.[166] The hybrid fibre metal laminate material GLARE (glass laminate aluminium reinforced epoxy) is used in the upper fuselage and on the stabilisers' leading edges.[167] This aluminium-glass-fibre laminate is lighter and has better corrosion and impact resistance than conventional aluminium alloys used in aviation.[168] Unlike earlier composite materials, GLARE can be repaired using conventional aluminium repair techniques. The application of GLARE on the A380 has a long history, which shows the complex nature of innovations in the aircraft industry.[169][170]

Newer weldable aluminium alloys are used in the A380's airframe. This enables the widespread use of laser beam welding manufacturing techniques, eliminating rows of rivets and resulting in a lighter, stronger structure.[171] High-strength aluminium (type 7449)[172] reinforced with carbon fibre was used in the wing brackets of the first 120 A380s to reduce weight, but cracks have been discovered and new sets of the more critical brackets will be made of standard aluminium 7010, increasing weight by 90 kg (198 lb).[173] Repair costs for earlier aircraft are expected to be around €500 million (US$629 million).[174]

It takes 3,600 L (950 US gal) of paint to cover the 3,100 m2 (33,000 sq ft) exterior of an A380.[175] The paint is five layers thick and weighs about 650 kg (1,433 lb).[176]

Avionics

The A380 employs an integrated modular avionics (IMA) architecture, first used in advanced military aircraft, such as the Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor, Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II,[177] and Dassault Rafale.[178] The main IMA systems on the A380 were developed by the Thales Group.[179] Designed and developed by Airbus, Thales and Diehl Aerospace, the IMA suite was first used on the A380. The suite is a technological innovation, with networked computing modules to support different applications.[179] The data networks use Avionics Full-Duplex Switched Ethernet, an implementation of ARINC 664. These are switched, full-duplex, star-topology and based on 100baseTX fast-Ethernet.[180] This reduces the amount of wiring required and minimises latency.[181]

Airbus used similar cockpit layout, procedures and handling characteristics to other Airbus aircraft, reducing crew training costs. The A380 has an improved glass cockpit, using fly-by-wire flight controls linked to side-sticks.[182][183] The cockpit has eight 15 by 20 cm (5.9 by 7.9 in) liquid crystal displays, all physically identical and interchangeable; comprising two primary flight displays, two navigation displays, one engine parameter display, one system display and two multi-function displays. The MFDs were introduced on the A380 to provide an easy-to-use interface to the flight management system—replacing three multifunction control and display units.[184] They include QWERTY keyboards and trackballs, interfacing with a graphical "point-and-click" display system.[185][186]

The Network Systems Server (NSS) is the heart of A380's paperless cockpit; it eliminates bulky manuals and charts traditionally used.[187][188] The NSS has enough inbuilt robustness to eliminate onboard backup paper documents. The A380's network and server system stores data and offers electronic documentation, providing a required equipment list, navigation charts, performance calculations, and an aircraft logbook. This is accessed through the MFDs and controlled via the keyboard interface.[181]

Power-by-wire flight control actuators have been used for the first time in civil aviation to back up primary hydraulic actuators. Also, during certain manoeuvres they augment the primary actuators.[189] They have self-contained hydraulic and electrical power supplies. Electro-hydrostatic actuators (EHA) are used in the aileron and elevator, electric and hydraulic motors to drive the slats as well as electrical backup hydrostatic actuators (EBHA) for the rudder and some spoilers.[190]

The A380's 350 bar (35 MPa or 5,000 psi) hydraulic system is a significant difference from the typical 210 bar (21 MPa or 3,000 psi) hydraulics used on most commercial aircraft since the 1940s.[191][192] First used in military aircraft, high-pressure hydraulics reduce the weight and size of pipelines, actuators and related components. The 350 bar pressure is generated by eight de-clutchable hydraulic pumps.[192][193] The hydraulic lines are typically made from titanium; the system features both fuel- and air-cooled heat exchangers. Self-contained electrically powered hydraulic power packs serve as backups for the primary systems, instead of a secondary hydraulic system, saving weight and reducing maintenance.[194]

The A380 uses four 150 kVA variable-frequency electrical generators,[195] eliminating constant-speed drives and improving reliability.[196] The A380 uses aluminium power cables instead of copper for weight reduction. The electrical power system is fully computerised and many contactors and breakers have been replaced by solid-state devices for better performance and increased reliability.[190]

Passenger provisions

The cabin has features to reduce traveller fatigue such as a quieter interior and higher pressurisation than previous generation of aircraft; the A380 is pressurised to the equivalent altitude of 1,520 m (5,000 ft) up to 12,000 m (39,000 ft).[197][198] It has 50% less cabin noise, 50% more cabin area and volume, larger windows, bigger overhead bins, and 60 cm (2.0 ft) extra headroom versus the 747-400.[199][200] Seating options range from 3-room 12 m2 (130 sq ft) "residence" in first class to 11-across in economy.[201] On other aircraft, economy seats range from 41.5 cm (16.3 in) to 52.3 cm (20.6 in) in width,[202] A380 economy seats are up to 48 cm (19 in) wide in a 10-abreast configuration;[203] compared with the 10-abreast configuration on the 747-400 which typically has seats 44.5 cm (17.5 in) wide.[204]

The A380's upper and lower decks are connected by two stairways, fore and aft, wide enough to accommodate two passengers side-by-side; this cabin arrangement allows multiple seat configurations. The maximum certified carrying capacity is 853 passengers in an all-economy-class layout,[53] Airbus lists the "typical" three-class layout as accommodating 525 passengers, with 10 first, 76 business, and 439 economy class seats.[137] Airline configurations range from Korean Air's 407 passengers to Emirates' two-class 615 seats for Copenhagen,[205] and average around 480–490 seats.[206][207] The Air Austral's proposed 840 passenger layout has not come to fruition. The A380's interior illumination system uses bulbless LEDs in the cabin, cockpit, and cargo decks. The LEDs in the cabin can be altered to create an ambience simulating daylight, night, or intermediate levels.[208] On the outside of the aircraft, HID lighting is used for brighter illumination.

Airbus's publicity has stressed the comfort and space of the A380 cabin,[209] and advertised onboard relaxation areas such as bars, beauty salons, duty-free shops, and restaurants.[210][211] Proposed amenities resembled those installed on earlier airliners, particularly 1970s wide-body jets,[212] which largely gave way to regular seats for more passenger capacity.[212] Airbus has acknowledged that some cabin proposals were unlikely to be installed,[211] and that it was ultimately the airlines' decision how to configure the interior.[212] Industry analysts suggested that implementing customisation has slowed the production speeds, and raised costs.[213] Due to delivery delays, Singapore Airlines and Air France debuted their seat designs on different aircraft prior to the A380.[214][215]

Initial operators typically configured their A380s for three-class service, while adding extra features for passengers in premium cabins. Launch customer Singapore Airlines introduced partly enclosed first class suites on its A380s in 2007, each featuring a leather seat with a separate bed; center suites could be joined to create a double bed.[216][217][218] A year later, Qantas debuted a new first class seat-bed and a sofa lounge at the front of the upper deck on its A380s,[219][220] and in 2009 Air France unveiled an upper deck electronic art gallery.[221] In late 2008, Emirates introduced "shower spas" in first class on its A380s allowing each first class passenger five minutes of hot water,[222][223] drawing on 2.5 tonnes of water although only 60% of it was used.[119] Emirates,[224][225] Etihad Airways and Qatar Airways also have a bar lounge and seating area on the upper deck, while Etihad has enclosed areas for two people each.[226] In addition to lounge areas, some A380 operators have installed amenities consistent with other aircraft in their respective fleets, including self-serve snack bars,[227] premium economy sections,[215] and redesigned business class seating.[214]

The Hamburg Aircraft Interiors Expo in April 2015 saw the presentation of an 11-seat row economy cabin for the A380. Airbus is reacting to a changing economy; the recession which began in 2008 saw a drop in market percentage of first class and business seats to six percent and an increase in budget economy travelers. Among other causes is the reluctance of employers to pay for executives to travel in First or Business Class. Airbus' chief of cabin marketing, Ingo Wuggestzer, told Aviation Week and Space Technology that the standard three class cabin no longer reflected market conditions. The 11 seat row on the A380 is accompanied by similar options on other widebodies: nine across on the Airbus A330 and ten across on the A350.[228]

Integration with infrastructure and regulations

Ground operations

In the 1990s, aircraft manufacturers were planning to introduce larger planes than the Boeing 747. In a common effort of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) with manufacturers, airports and its member agencies, the "80-metre box" was created, the airport gates allowing planes up to 80 m (260 ft) wingspan and length to be accommodated.[229] Airbus designed the A380 according to these guidelines,[230][231] and to operate safely on Group V runways and taxiways with a 60 metres (200 ft) loadbearing width.[232] The US FAA initially opposed this,[233][234] then in July 2007, the FAA and EASA agreed to let the A380 operate on 45 m (148 ft) runways without restrictions.[235] The A380-800 is approximately 30% larger in overall size than the 747-400.[236][237] Runway lighting and signage may need changes to provide clearance to the wings and avoid blast damage from the engines. Runways, runway shoulders and taxiway shoulders may be required to be stabilised to reduce the likelihood of foreign object damage caused to (or by) the outboard engines, which are more than 25 m (82 ft) from the centre line of the aircraft,[230][232][238] compared to 21 m (69 ft) for the 747–400,[239] and 747–8.[240]

Airbus measured pavement loads using a 540-tonne (595 short tons) ballasted test rig, designed to replicate the landing gear of the A380. The rig was towed over a section of pavement at Airbus' facilities that had been instrumented with embedded load sensors.[241] It was determined that the pavement of most runways will not need to be reinforced despite the higher weight,[238] as it is distributed on more wheels than in other passenger aircraft with a total of 22 wheels (that is, its ground pressure is lower).[242] The A380 undercarriage consists of four main landing gear legs and one noseleg (a similar layout to the 747), with the two inboard landing gear legs each supporting six wheels.[242][243]

The A380 requires service vehicles with lifts capable of reaching the upper deck,[244] as well as tractors capable of handling the A380's maximum ramp weight.[245] When using two jetway bridges the boarding time is 45 min, and when using an extra jetway to the upper deck it is reduced to 34 min.[246] The A380 has an airport turnaround time of 90–110 minutes.[119] In 2008 the A380 test aircraft were used to trial the modifications made to several airports to accommodate the type.[247]

Takeoff and landing separation

.jpg)

In 2005, the ICAO recommended that provisional separation criteria for the A380 on takeoff[248] and landing be substantially greater than for the 747 because preliminary flight test data suggested a stronger wake turbulence.[249][250] These criteria were in effect while the ICAO's wake vortex steering group, with representatives from the JAA, Eurocontrol, the FAA, and Airbus, refined its 3-year study of the issue with additional flight testing. In September 2006, the working group presented its first conclusions to the ICAO.[251][252]

In November 2006, the ICAO issued new interim recommendations. Replacing a blanket 10 nautical miles (19 km) separation for aircraft trailing an A380 during approach, the new distances were 6 nmi (11 km), 8 nmi (15 km) and 10 nmi (19 km) respectively for non-A380 "Heavy", "Medium", and "Light" ICAO aircraft categories. These compared with the 4 nmi (7.4 km), 5 nmi (9.3 km) and 6 nmi (11 km) spacing applicable to other "Heavy" aircraft. Another A380 following an A380 should maintain a separation of 4 nmi (7.4 km). On departure behind an A380, non-A380 "Heavy" aircraft are required to wait two minutes, and "Medium"/"Light" aircraft three minutes for time based operations. The ICAO also recommends that pilots append the term "Super" to the aircraft's callsign when initiating communication with air traffic control, to distinguish the A380 from "Heavy" aircraft.[253]

In August 2008, the ICAO issued revised approach separations of 4 nmi (7.4 km) for Super (another A380), 6 nmi (11 km) for Heavy, 7 nmi (13 km) for medium/small, and 8 nmi (15 km) for light.[254] In November 2008, an incident on a parallel runway during crosswinds made the Australian authorities change procedures for those conditions.[255]

Singapore Airlines describe the A380's landing speed of 130–135 kn (240–250 km/h) as "impressively slow".[256]

Maintenance

As the A380 fleet grows older, airworthiness authority rules require certain scheduled inspections from approved aircraft tool shops. The increasing fleet size (to about 286 in 2020) cause expected maintenance and modification to cost $6.8 billion for 2015–2020, of which $2.1 billion are for engines. Emirates performed its first 3C-check for 55 days in 2014. During lengthy shop stays, some airlines will use the opportunity to install new interiors.[257]

Variants

A380F

Airbus originally accepted orders for the freighter variant, offering the largest payload capacity of any cargo aircraft in production, exceeded only by the single Antonov An-225 Mriya in service.[258] An aerospace consultant has estimated that the A380F would have 7% better payload and better range than the Boeing 747-8F, but also higher trip costs.[259] However, production was suspended until the A380 production lines have settled with no firm availability date.[73][74][75] In 2015, Airbus removed A380F from the range of freighters on its corporate website.[260] The maximum payload would have been 150 t (330,000 lb), with a 5,600 nmi (10,400 km) range.[139]

On 9 July 2015, Business Insider reported that Airbus had filed a patent application for an A380 "combi" which would offer the flexibility of carrying both passengers and cargo, along with being rapidly reconfigurable to expand or contract the cargo area and passenger area as needed for a given flight.[261]

A380-900

In November 2007, Airbus top sales executive and chief operating officer John Leahy confirmed plans for an enlarged variant, the A380-900, with more seating space than the A380-800.[262] This would have a seating capacity for 650 passengers in standard configuration, and approximately 900 passengers in an economy-only configuration.[263] Airlines that had expressed an interest in the −900 included Emirates,[264] Virgin Atlantic,[265] Cathay Pacific,[266] Air France, KLM, Lufthansa,[267] Kingfisher Airlines,[268] and leasing company ILFC.[269] In May 2010, Airbus announced that A380-900 development was postponed, until production of the A380-800 stabilises.[270]

On 11 December 2014 at the annual Airbus Investor Day forum Airbus CEO controversially announced that "We will one day launch an A380neo and one day launch a stretched A380"[271] following speculation sparked by Airbus CFO Harald Wilhelm stating that Airbus could axe the A380 ahead of its time due to softening demand.[272] On 15 June 2015, John Leahy, Airbus's chief operating officer for customers, stated Airbus was looking at the A380-900 programme again. Airbus's newest concept is a stretch of the A380-800 offering 50 seats more, not 100 as originally envisaged. The stretch would be tied to a potential re-engining of the A380-800. According to Flight Global, an A380-900 would make better use of the A380's existing wing.[273]

A380neo

On 15 June 2015, Reuters reported that Airbus was discussing a stretched version of the A380 with a half dozen customers. This aircraft, which could also feature new engines, would accommodate an additional fifty passengers. Deliveries to customers were planned for sometime in 2020 or 2021.[274] On 19 July 2015, Airbus CEO Fabrice Brégier stated that the company will build a new version of the A380 featuring new improved wings and new engines.[275] Speculation about the development of a so-called A380neo (neo for new engine option) had been going on for a few months after earlier press releases in 2014,[276] and in 2015 the company was considering whether to end production of the type prior to 2018[277] or develop a new A380 variant. Later it was revealed that Airbus was looking at both the possibility of a longer A380 in line of the previously planned A380-900[278] and a new engine version, i.e. A380neo. Brégier also revealed that the new variant would be ready to enter service by 2020.[279] The engine would most likely be one of a variety of all-new options from Rolls-Royce, ranging from derivatives of the A350's XWB-84/97 to the future Advance project due at around 2020.[280][281]

On 3 June 2016, Emirates President Tim Clark stated that talks between Emirates and Airbus on the A380neo have "lapsed".[282] On 12 June 2017, Fabrice Brégier confirmed that Airbus will not launch an A380neo, stating "...there is no business case to do that, this is absolutely clear." However, Brégier stated it won't stop Airbus from looking at what could be done to improve the performance of the aircraft. One such proposal is a 32 ft (9.8 m) wingspan extension to reduce drag and increase fuel efficiency by 4%,[283] though further is seen the aircraft with new Sharklets.[284]

A380plus

Launched at the June 2017 Paris Air Show, Airbus offers an A380plus enhanced version with 13% lower costs per seat, featuring up to 80 more seats through better use of cabin space, split scimitar winglets and wing refinements allowing a 4% fuel economy improvement and longer aircraft maintenance intervals with less downtime.[285] Its maximum takeoff weight is increased by 3 t (6,600 lb) to 578 t (1,274,000 lb), allowing it to carry more passengers over the same 8,200 nmi range or increase the range by 300 nm. Emirates could order 20 aircraft at the November Dubai Air Show.[286]

The upgrade will be available from 2020, 4.7 m (15 ft) winglets mockups are displayed on the MSN04 test aircraft at Le Bourget. Wing twist will be modified and its camber changed by increasing its height by 33 mm (1.3 in) between Rib 10 and Rib 30, along with upper-belly fairing improvements. The in-flight entertainment, the flight management system and the fuel pumps will come from the A350 to reduce weight and improve reliability and fuel economy. Light checks will be required after 1,000 hr instead of 750 hr and as heavy check downtime will be reduced to keep the aircraft flying for six days more per year.[287]

Market

.jpg)

Size

The very large aircraft (VLA) market, with more than 400 seats, is estimated for two decades at more than 1,700 by Airbus and 700 by Boeing since 1999-2000.[288] In 2006, industry analysts Philip Lawrence of the Aerospace Research Centre in Bristol anticipated 880 sales by 2025 with Airbus having conducted the most extensive and thorough market analysis of commercial aviation ever undertaken, justifying its VLA plans to design the A380 by the spoke-hub distribution paradigm while Richard Aboulafia of the consulting Teal Group in Fairfax, Virginia anticipated 400 with the rise of mid-size aircraft and market fragmentation reducing them to niche markets, making such plans unjustified in a point-to-point transit model.[26]

In 2007, Airbus estimated a demand for 1,283 VLA in the following 20 years if airport congestion remains constant, up to 1,771 VLAs if congestion increases, with most deliveries (56%) in Asia-Pacific, and 415 very large, 120-tonne plus freighters.[289] For the same period, Boeing was estimating the demand for 590 large (B747 or A380) passenger airliners and 630 freighters.[290]

Frequency and capacity

Cathay Pacific or Singapore Airlines need to balance frequency and capacity.[291] China Southern struggled two years to use its A380s from Beijing and finally received Boeing 787s in Guangzhou where it is based, which can’t command a premium unlike Beijing or Shanghai.[292][293] In 2013, Air France withdrew A380 services to Singapore and Montreal and switched to smaller aircraft.[294]

In 2014, British Airways replaced three 777 flights between London and Los Angeles with two A380 per day.[295] Emirates' Tim Clark sees a large potential for Asian A380-users, and criticised Airbus' marketing efforts.[296] As business travelers prefers more choices offered by more frequencies, flying a route multiple times on smaller aircraft rather than once on a large plane, United Airlines observed the A380 "just doesn't really work for us" as it relies on Boeing 787s operating at a lower trip cost.[297]

Production

In 2005, 270 sales were necessary to attain break-even and with 751 expected deliveries its Internal rate of return outlook was at 19%, but due to disruptions in the ramp-up leading to overcosts and delayed deliveries, it increased to 420 in 2006.[298] In 2010, EADS CFO Hans Peter Ring said that break-even could be achieved by 2015 when 200 deliveries were projected.[299] In 2012, Airbus clarified that the aircraft production costs would be less than its sales price.[93]

On 11 December 2014, Airbus chief financial officer Harald Wilhelm hinted the possibility of ending the programme in 2018, disappointing Emirates president Tim Clark.[300] Airbus shares fell down consequently.[301] Airbus responded to the protests by playing down the possibility the A380 would be abandoned, instead emphasising that enhancing the airplane was a likelier scenario.[302] On 22 December, as the jet was about to break even, Airbus CEO Fabrice Brégier ruled out cancelling it.[303]

Ten years after its first flight, Brégier said it was "almost certainly introduced ten years too early".[304] While no longer losing money on each plane sold, Airbus admits that the company will never recoup the $25 billion investment it made in the project.[305]

Cost

As of 2016 the list price of an A380 is US$432.6 million.[306] Negotiated discounts made the actual prices much lower, and industry experts questioned whether the A380 project would ever pay for itself.[93] The first aircraft was sold-and-leased-back by Singapore Airlines in 2007 to Dr. Peters for $197 million.[307]

An A380's hourly cost is about $26,000, or around $50 per seat hour, which compares to $44 per seat hour for a Boeing 777-300ER, and $90 per seat hour for a Boeing 747-400 as of November 2015.[308]

Secondary

As of mid-2015, several airlines have expressed their interest in selling their aircraft, partially coinciding with expiring lease contracts for the aircraft. Several A380 which are in service have been offered for lease to other airlines. The suggestion has prompted concerns on the potential for new sales for Airbus, although these were dismissed by Airbus COO John Leahy stated that "Used A380s do not compete with new A380s", stating that the second-hand market is more interesting for parties otherwise looking to buy smaller aircraft such as the Boeing 777.[309]

After Malaysia Airlines was unable to sell or lease its six A380s, it decided to refurbish the aircraft with seating for 700 and transfer them to a subsidiary carrier for religious pilgrimage flights.[310] As it will receive its six A350s to replace its six A380s starting in December 2017, the new subsidiary will serve the Hajj and Umrah market with them, starting in the third quarter of 2018 and could be expanded above six beyond 2020 to 2022. The cabin will have 36 business seats and 600 economy seats, with a 712 seats reconfiguration possible within five days. The fleet could be chartered half the year for the tourism industry like cruise shipping and will be able to operate for the next 40 years if oil prices stay low.[311]

With four leased to Singapore Airlines which will return them between October 2017 and March 2018, Dr. Peters fears a weak aftermarket and considers scrapping them while they are on sale for a business jet conversion, but on the other hand Airbus sees a potential for African airlines and Chinese airlines, Hajj charters and its large Gulf operators.[312]

Orders and deliveries

Nineteen customers have ordered the A380. Total orders for the A380 stand at 317 as of July 2017.[2] The biggest customer is Emirates, which has ordered or committed to order a total of 142 A380s as of 31 July 2017.[2][313] One VIP order was made in 2007[314] but later cancelled by Airbus.[315] The A380F version attracted 27 orders, before they were either cancelled (20) or converted to A380-800 (7) following the production delay and the subsequent suspension of the freighter program.

Delivery takes place in Hamburg for customers from Europe and the Middle East and in Toulouse for customers from the rest of the world.[316] EADS explained that deliveries in 2013 were to be slowed temporarily to accommodate replacement of the wing rib brackets where cracks were detected earlier in the existing fleet.[317]

In 2013, in expectation of raising the number of orders placed, Airbus announced 'attractable discounts' to airlines who placed large orders for the A380. Soon after, at the November 2013 Dubai Air Show where it ordered 150 B777X, Emirates ordered 50 aircraft, totalling $20 billion.[318]

In 2014, Airbus said that some ordered A380s might not be built for an undisclosed Japanese airline. Virgin Atlantic has ordered six A380s but is undecided about accepting them. Qantas planned to order eight more airplanes but is in doubt due to a cost-cutting drive. Amedeo, an aircraft lessor that ordered 20 A380s, had not found a client for the airliner as of 2014.[319]

In June 2017, Emirates has 48 orders outstanding but due to lack of space in Dubai Airport, it deferred 12 deliveries by one year and will not take any in 2019-20 before replacing its early airliners from 2021: there are open production slots in 2019 and Airbus reduced its production rate at 12 per year for 2017-18. The real backlog is much smaller than the official 107 with 47 uncertain orders: 20 commitments for the A380-specialized lessor Amedeo which commits to production only once aircraft are placed, eight for Qantas which wants to keep its fleet at 12, six for Virgin Atlantic which does not want them anymore and three ex Transaero for finance vehicle Air Accord.[320]

Timeline

| 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Total | ||

| Net orders | A380-800 | 78 | – | 34 | 10 | 10 | 24 | 33 | 9 | 4 | 32 | 19 | 9 | 42 | 13 | 2 | – | −2 | 317 |

| A380F | 7 | 10 | – | – | 10 | -17 | -10 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Deliveries | A380-800 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 12 | 10 | 18 | 26 | 30 | 25 | 30 | 27 | 28 | 7 | 214 |

Cumulative orders and deliveries

Orders

Deliveries

Operators

There were 214 aircraft in service with 13 operators as of 31 July 2017.[322]

- Singapore Airlines first service on 25 October 2007[101]

- Emirates first service on 1 August 2008[107]

- Qantas first service on 20 October 2008[108]

- Air France first service on 20 November 2009[323]

- Lufthansa first service on 6 June 2010[324]

- Korean Air first service on 17 June 2011[325]

- China Southern Airlines first service on 17 October 2011[326][327]

- Malaysia Airlines first service on 1 July 2012[328]

- Thai Airways first service on 6 October 2012[329]

- British Airways first service on 2 August 2013[330]

- Asiana Airlines first service on 13 June 2014[331]

- Qatar Airways first service on 10 October 2014[332]

- Etihad Airways first service on 27 December 2014[333]

Notable routes

The shortest regular commercial route that the A380 flies is from Dubai to Doha (379 km or 236 miles) with Emirates.[334] (This route has been suspended due to diplomatic relations with Qatar.[335]) Air France briefly operated the A380 on the shorter Paris Charles de Gaulle to London Heathrow route (344 km or 214 miles) in mid-2010.[336] The longest A380 route — and the second longest non-stop commercial flight in the world — is Emirates from Dubai to Auckland at 14,203 kilometres (8,825 mi).[337]

Incidents and accidents

The A380 has been involved in one aviation occurrence and no hull loss accidents with no fatalities as of June 2017, according to the Aviation Safety Network.[338][339]

On 4 November 2010, Qantas Flight 32, en route from Singapore Changi Airport to Sydney Airport, suffered an uncontained engine failure, resulting in a series of related problems, and forcing the flight to return to Singapore. There were no injuries to the passengers, crew or people on the ground despite debris falling onto the Indonesian island of Batam.[340] The A380 was damaged sufficiently for the event to be classified as an accident.[341] Qantas subsequently grounded all of its A380s that day subject to an internal investigation taken in conjunction with the engine manufacturer Rolls-Royce plc. A380s powered by Engine Alliance GP7000 were unaffected but operators of Rolls-Royce Trent 900-powered A380s were affected. Investigators determined that an oil leak, caused by a defective oil supply pipe, led to an engine fire and subsequent uncontained engine failure.[342] Repairs cost an estimated A$139 million (~US$145M).[343] As other Rolls-Royce Trent 900 engines also showed problems with the same oil leak, Rolls-Royce ordered many engines to be changed, including about half of the engines in the Qantas A380 fleet.[344] During the airplane's repair, cracks were discovered in wing structural fittings which also resulted in mandatory inspections of all A380s and subsequent design changes.[124]

Specifications

| Variant | A380-800[138] |

|---|---|

| Cockpit crew | Two |

| Typical seating | 544 (4-class) |

| Exit limit | 868[345] |

| Length overall | 72.72 m (238 ft 7 in) |

| Wingspan | 79.75 m (261 ft 8 in) |

| Height | 24.09 m (79 ft 0 in) |

| Wheelbase | 31.88 m (104 ft 7 in) |

| Wheel track | 12.46 m (40 ft 11 in), 14.34 m (47 ft 1 in) total width[230] |

| Outside fuselage dimensions |

Width: 7.14 m (23 ft 5 in) Height: 8.41 m (27 ft 7 in) |

| Maximum cabin width |

6.50 m (21 ft 4 in) main deck 5.80 m (19 ft 0 in) upper deck |

| Cabin length | 49.9 m (163 ft 9 in) main deck 44.93 m (147 ft 5 in) upper deck |

| Wing area | 845 m2 (9,100 sq ft)[346] |

| Aspect ratio | 7.53 |

| Wing sweep | 33.5°[346] |

| Maximum ramp weight | 577 t (1,272,000 lb) |

| Maximum take-off weight | 575 t (1,268,000 lb) |

| Max. landing weight | 394 t (869,000 lb) |

| Max. zero fuel weight | 369 t (814,000 lb) |

| Operating empty weight | 276.8 t (610,000 lb)[347] |

| Max. structural payload | 84 t (185,000 lb)[230] |

| Maximum cargo volume | 184 m3 (6,500 cu ft) |

| Maximum operating speed | Mach 0.89 (945 km/h; 511 kn) |

| Maximum design speed | Mach 0.96 (1,020 km/h; 551 kn)[lower-alpha 1][348] |

| Cruise speed | Mach 0.85 (903 km/h; 488 kn)[152] |

| Take off (MTOW, SL, ISA) | 3,000 m (9,800 ft)[230] |

| Landing speed | 130 kn (240 km/h)[152] |

| Range | 15,200 km / 8,200 nmi |

| Service ceiling | 13,100 m (43,000 ft)[349] |

| Max. fuel capacity | 323,545 L / 85,471 USgal[350] |

| Engines (4 ×) | Engine Alliance GP7200 / Rolls-Royce Trent 900 |

| Thrust (4 ×) | 311 kN (70,000 lbf) |

| Variant | Certification | Engine | Thrust |

|---|---|---|---|

| A380-841 | 12 December 2006 | Trent 970-84/970B-84 | 348.31 kN |

| A380-842 | 12 December 2006 | Trent 972-84/972B-84 | 356.81 kN |

| A380-861 | 14 December 2007 | Engine Alliance GP7270 | 332.44 kN |

See also

- Related development

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

- List of jet airliners

- List of aerospace megaprojects

- List of Airbus A380 orders and deliveries

- Seat configurations of the Airbus A380

References

- ↑ in dive at cruise altitude

- ↑ Final assembly in France

- 1 2 3 4 5 Orders & Deliveries summary. Airbus, 31 July 2017.

- 1 2 Alan Tovey (18 Jan 2015). "Is Airbus's A380 a 'superjumbo' with a future or an aerospace white elephant?". The Telegraph.

- 1 2 Christopher Jasper and Andrea Rothman (12 Jul 2016). "Airbus A380 Cut May Mark Beginning of End for Superjumbo". Bloomberg.

- ↑ "2017 price adjustment for Airbus’ modern, fuel-efficient aircraft". Airbus. 11 Jan 2017. Retrieved 5 Jul 2017.

- ↑ How EADS Became Airbus Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Airbus Industrie Archived 11 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine. at britannica.com

- ↑ "Airbus A380 Facts & Figures". Airbus. June 2016.

- ↑ Kingsley-Jones, Max (17 February 2006). "Boeing's 747-8 vs. A380: A titanic tussle". Flight International. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ↑ Norris, 2005. p. 7

- ↑ "MDC brochures for undeveloped versions of the MD-11 and MD-12". md-eleven.net. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "McDonnell Douglas Unveils New MD-XX Trijet Design". McDonnell Douglas. 4 September 1996. Archived from the original on 2011-11-06. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Norris, 2005. pp. 16–17

- ↑ Norris, 2005. pp. 17–18

- ↑ Norris, 2005. p. 31

- 1 2 Norris, Guy (14 June 2005). "Creating A Titan". Flight International. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Boeing, partners expected to scrap Super-Jet study". Los Angeles Times. 10 July 1995. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Bowen, David (4 June 1994). "Airbus will reveal plan for super-jumbo: Aircraft would seat at least 600 people and cost dollars 8bn to develop". The Independent. UK. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Sweetman, Bill (1 October 1994). "Airbus hits the road with A3XX". Interavia Business & Technology. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Norris, Guy; Mark Wagner (2005). Airbus A380: Superjumbo of the 21st Century. Zenith Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-2218-5.

- ↑ "Aviation giants have Super-jumbo task". Orlando Sentinel. 27 November 1994. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Norris, Guy (10 September 1997). "Boeing looks again at plans for NLA". Flight International. Archived from the original on 1 June 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ↑ "Superjumbo or white elephant?". Flight International. 1 August 1995. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Harrison, Michael (23 October 1996). "Lehman puts $18bn price tag on Airbus float". The Independent. UK. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Cannegieter, Roger. "Long Range vs. Ultra High Capacity" (PDF). aerlines.nl. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 Scott Babka (5 September 2006). "EADS: the A380 Debate" (PDF). Morgan Stanley.

- ↑ Lawler, Anthony (4 April 2006). "Point-To-Point, Hub-To-Hub: the need for an A380 size aircraft" (PDF). Leeham.net. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ↑ Pae, Peter (20 December 2000). "Airbus Giant-Jet Gamble OKd in Challenge to Boeing; Aerospace: EU rebuffs Clinton warning that subsidies for project could lead to a trade war". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "The Casino in the Sky". Wired. Associated Press. 19 December 2000. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Airbus jumbo on runway". CNN. 19 December 2000. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Virgin orders six A3XX aircraft, allowing Airbus to meet its goal". The Wall Street Journal. 15 December 2000. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Skylon Assessment Report" (PDF). UK Space Agency. April 2011. p. 18. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- 1 2 Yann Philippin (7 May 2012). "Airbus encaisse les coûts de l’A380". Libération (in French).

- ↑ Bloomberg (December 13, 2004). "Airbus Says Its A380 Jet Is Over Budget". New York Times.

- ↑ Karl West (Dec 28, 2014). "Airbus's Flagship Plane May Be Too Big To Be Profitable". The Guardian. Business Insider.

- ↑ Andrew Stevens and Jethro Mullen (February 17, 2016). "Airbus CEO upbeat on future of A380 after new orders". CNNMoney.

- ↑ Richard Aboulafia (Jun 6, 2016). "Airbus A380: The Death Watch Begin". Forbes.

- 1 2 Morales, Jesus. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 2016-02-07. "The A380 Transport Project and Logistics – Assessment of alternatives", p. 19, Airbus, 18 January 2006. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ↑ "Airbus delivers first A380 fuselage section from Spain". Airbus. 6 November 2003. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ↑ "Planes that changed the World, Episode #3: A380 Superjumbo" Archived 7 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. Smithsonian Channel

- ↑ "Convoi Exceptionnel". Airliner World. Key Publishing Ltd. May 2009.

- ↑ "A380: topping out ceremony in the equipment hall. A380: special transport ship in Hamburg for the first time". Airbus Press Centre. 10 June 2004. Archived from the original on 12 March 2008. Retrieved 19 June 2009.

- 1 2 "Towards Toulouse". Flight International. 20 May 2003. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "A380 convoys". IGG.FR. 28 October 2007. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 Kingsley-Jones, Max (20 December 2005). "A380 powers on through flight-test". Flight International. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Madslien, Jorn (18 January 2005). "Giant plane a testimony to 'old Europe'". BBC News. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "A380, the 21st century flagship, successfully completes its first flight". Airbus. 27 April 2005. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ↑ Sparaco, Pierre. "A titan takes off Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine." Aviation Week & Space Technology, May 2005. Archive

- ↑ "It flies! But will it sell? Airbus A380 makes maiden flight, but commercial doubts remain". Associated Press. 27 April 2005. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Airbus 380 conducts test flights in Addis Ababa". Ethiopian Reporter. 21 November 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Airbus tests A380 jet in extreme cold of Canada". MSNBC. 8 February 2006. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Airbus to reinforce part of A380 wing after March static test rupture". Flight International. 23 May 2006. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 Daly, Kieran (6 April 2006). "Airbus A380 evacuation trial full report: everyone off in time". Flight International. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ↑ "Airbus infrared video Archived 30 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine." 7 April 2011.

- ↑ "Pictures: Airbus A380 clears European and US certification hurdles for evacuation trial". Flight International. 29 March 2006. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ↑ "GE joint venture engines tested on Airbus A380". Business Courier. 25 August 2006. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Airbus test flight with engine alliance engine a success". PR Newswire. 28 August 2006. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- 1 2 "Airbus A380 completes test flight". BBC News. 4 September 2006. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Ramel, Gilles (11 November 2006). "Airbus A380 jets off for tests in Asia from the eye of a storm". USA Today. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Whelan, Ian. "Long-serving Flight Test Aircraft Play Different Roles" AINonline, 21 August 2014. Accessed: 4 September 2014. Video Archived 9 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "EASA Type-Certificate Data Sheet TCDS A.110 Issue 03" (PDF). EASA. 14 December 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 "FAA Type Certificate Data Sheet NO.A58NM Rev 2" (PDF). FAA. 14 December 2007. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Doc 8643 – Edition 40, Part1-By Manufacturer Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine." page 1-8. International Civil Aviation Organization, 30 March 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ↑ Heinen, Mario (19 October 2006). "The A380 programme" (PDF). EADS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2006. Retrieved 19 October 2006.

- ↑ Kingsley-Jones, Max (18 July 2006). "The race to rewire the Airbus A380". Flight International. Archived from the original on 2007-10-12. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Clark, Nicola (6 November 2006). "The Airbus saga: Crossed wires and a multibillion-euro delay". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Kenneth Wong (6 December 2006). "What Grounded the Airbus A380?". Cadalyst Manufacturing. Archived from the original on 26 August 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Crane, Mary (6 June 2006). "Major turbulence for EADS on A380 delay". Forbes. Archived from the original on 12 August 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Clark, Nicola (5 June 2006). "Airbus delay on giant jet sends shares plummeting". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Clark, Nicola (4 September 2006). "Airbus replaces chief of jumbo jet project". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Airbus confirms further A380 delay and launches company restructuring plan". Airbus. 3 October 2006. Archived from the original on 14 October 2006. Retrieved 3 October 2006.

- ↑ Robertson, David (3 October 2006). "Airbus will lose €4.8bn because of A380 delays". The Times. UK. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 "A380 Freighter delayed as Emirates switches orders". Flight International. 16 May 2006. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 Quentin Wilber, Dell (8 November 2006). "Airbus bust, Boeing boost". The Washington Post. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 Carter Dougherty, Leslie Wayne (8 November 2006). "FedEx Rescinds Order for Airbus A380s". The New York Times. Frankfurt. The New York Times. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ↑ Clark, Nicola (2 March 2007). "UPS cancels Airbus A380 order". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ↑ "ILFC to defer its Airbus A380 order until at least 2013, ditching freighter variants for passenger configuration". Flight International. 4 December 2006. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Airbus says A380F development 'interrupted'". Flight International. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Airbus has no timeline on the A380 freighter". Flight International. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Emirates Airlines reaffirms commitment to A380 and orders additional four". Airbus. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ↑ "Singapore Airlines boosts Airbus fleet with additional A380 orders". Airbus. Archived from the original on 28 December 2007. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ↑ "Qantas signs firm order for eight additional A380s". Airbus. Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ↑ "Air France to order two additional A380s and 18 A320 Family aircraft". Airbus. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ↑ "Qatar Airways confirms order for 80 A350 XWBs and adds three A380s". Airbus. Archived from the original on 22 June 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ↑ "Korean Air expands A380 aircraft order". Airbus. Archived from the original on 2 August 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ↑ Pae, Peter (January 18, 2009). "Airbus could build next Air Force One; 747 due to be replaced". Seattle Times.

- ↑ "US considers Airbus A380 as Air Force One and potentially a C-5 replacement". Flight International. 17 October 2007.

- ↑ "EADS waves off bid for Air Force One replacement". Flight International. January 28, 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-02-03.

- ↑ "A380 production ramp-up revisited". Airbus. 13 May 2008. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Airbus Expects Sharp Order Drop in 2009". Aviation Week & Space Technology. 15 January 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Rothman, Andrea (30 December 2009). "Airbus Fell Short with 10 A380s in 2009". Business Week. Archived from the original on 16 April 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 Rothman, Andrea (17 January 2011). "Airbus Beats Boeing on 2010 Orders, Deliveries as Demand Recovery Kicks In". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 Daniel Michaels (13 July 2012). "Airbus Wants A380 Cost Cuts"

. The Wall Street Journal.

. The Wall Street Journal. - ↑ "Airbus slashes production of A380 superjumbo". Financial Times. 12 July 2016.

- ↑ "Airbus A380 Cut May Mark Beginning of End for Superjumbo". July 12, 2016.

- ↑ NY Times: Airbus Cuts Delivery Goal for A380 Jumbo Jets Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ WSJ: Airbus Cuts A380 Production Plans Archived 10 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Jens Flottau (Jun 5, 2017). "Airbus confirms more A380 production cuts". Aviation Week Network.

- ↑ "Airbus reports Half-Year (H1) 2017 results" (Press release). Airbus. 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "BBC Two: 'How to build a superjumbo wing'". BBC. 23 November 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 "Singapore Airlines – Our History". Singapore Airlines. 1 November 2012. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ↑ "A380 superjumbo lands in Sydney". BBC. 25 October 2007. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "SIA's Chew: A380 pleases, Virgin Atlantic disappoints". ATW Online. 13 December 2007. Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- ↑ Flottau, Jens (21 November 2012). "Emirates A350-1000 Order 'In Limbo'". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

Clark points out that "the faster you fly [the A380], the more fuel-efficient she gets; when you fly at [Mach] 0.86 she is better than at 0.83."

- ↑ ""Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 July 2015. Retrieved 2014-06-19. Technical Issues", Flightglobal, undated. Accessed: 20 June 2014.

- ↑ "Emirates A380 arrives in New York!". 3 August 2008. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 "Emirates A380 Lands at New York's JFK". 1 August 2008. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 "Qantas A380 arrives in LA after maiden flight". The Age. Australia. 21 October 2008. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Airbus narrowly meets delivery target of 12 A380s in 2008". Flight International. 30 December 2008. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Singapore Airlines celebrates its first millionth A380 passenger". WebWire. 19 February 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Airbus A380: Mehr als 1,5 Millionen Passagiere". FlugRevue. 11 May 2009.

- ↑ Michaels, Daniel (30 October 2009). "Strong Euro Weighs on Airbus, Suppliers". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Air France set to get Europe's first A380 superjumbo". MSN News. 30 October 2009.

- ↑ "Lufthansa übernimmt A380 am 19. Mai – Trainingsflüge in ganz Deutschland". Flugrevue.de. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ↑ "Airbus delivers tenth A380 in 2010" (Press release). 16 July 2011. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- ↑ "The A380 global fleet spreads its wings as deliveries hit the 'century mark'". Airbus (Press release). 14 March 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ↑ "Where is the A380 flying?". airbus.com. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Jens Flottau (29 October 2015). "Airbus A380 After Eight Years In Service". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- 1 2 3 "Looking forward Archived 27 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine." Flightglobal, undated. Accessed: 20 June 2014.

- ↑ "Airbus poised to start building new higher-weight A380 variant". Flight International. 18 May 2010. Archived from the original on 21 May 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ↑ "British Airways and Emirates will be first for new longer-range A380". Flight International. 14 May 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- 1 2 Hamilton, Scott. "Updating the A380: the prospect of a neo version and what’s involved" Leehamnews.com, 3 February 2014. Accessed: 21 June 2014. Archived on 8 April 2014.

- ↑ "Airbus to offer higher-weight A380 from 2013". Flight International. 20 February 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- 1 2 "EASA mandates prompt detailed visual inspections of the wings of 20 A380s". EASA. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ↑ Hradecky, Simon (21 January 2012). "Airworthiness Directive regarding Airbus A380 wing cracks". The Aviation Herald.

- ↑ "EASA AD No.:2012-0013" (PDF). EASA. 20 January 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ↑ Rob Waugh (9 January 2012). "World's biggest super-jumbos must be GROUNDED, say engineers after cracks are found in the wings of three Airbus A380s". London: The Daily Mail.

- ↑ "Airbus Adjusts A380 Assembly Process". Aviation Week & Space Technology. 26 January 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ↑ "Airbus to inspect all A380 superjumbos for wing cracks". BBC News. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ↑ "A380 Repairs to cost Airbus 105 million pounds". Air Transport World. 14 March 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ↑ "Air France seeks Airbus compensation for A380 glitches: report". DefenceWeb. 1 November 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ↑ "Airbus A380 wing repairs could take up to eight weeks". BBC News. 11 June 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ↑ "Druckabfall im A380: Airbus muss jede zehnte Tür umbauen". Der Spiegel. 18 June 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ↑ "Erhebliche Probleme mit Türen des Airbus A380". NDR Presse und Information. 18 June 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ↑ "Singapore Airlines A380 plane in emergency landing". BBC News. 6 January 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ↑ "Airbus A380 Cabin". Airbus. Archived from the original on 2009-08-25. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 Martin, Mike (18 June 2007). "Honey, I shrunk the A380!". Flight International. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- 1 2 "A380 Specifications". Airbus. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- 1 2 "The triple-deck cargo hauler". Airbus. Archived from the original on 22 August 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ↑ "Trent 900 engine". Rolls-Royce. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ↑ "GP7200 engine features". Engine Alliance. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ↑ "Environment". Lufthansa. Archived from the original on 3 July 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ↑ "A380 Family". Airbus. Archived from the original on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 25 October 2009.