Superior vena cava

| Superior vena cava | |

|---|---|

Veins | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | common cardinal veins |

| Source | brachiocephalic vein, azygos vein |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vena cava superior, vena maxima |

| MeSH | A07.231.908.949.815 |

| TA | A12.3.03.001 |

| FMA | 4720 |

The superior vena cava (SVC) is the superior of the two venae cavae, the great venous trunks that return deoxygenated blood from the systemic circulation to the right atrium of the heart. It is a large-diameter (24 mm), yet short, vein that receives venous return from the upper half of the body, above the diaphragm. (Venous return from the lower half, below the diaphragm, flows through the inferior vena cava.) The SVC is located in the anterior right superior mediastinum.[1] It is the typical site of central venous access (CVA) via a central venous catheter or a peripherally inserted central catheter. Mentions of "the cava" without further specification usually refer to the SVC.

Structure and Course of superior vena cava

It is formed by the left and right brachiocephalic veins (also referred to as the innominate veins), which also receive blood from the upper limbs, eyes and neck, behind the lower border of the first right costal cartilage. It passes vertically downwards behind first intercostal space and receives azygos vein just before it pierces the fibrous pericardium opposite right second costal cartilage and its lower part is intrapericardial. And then, it ends in the upper and posterior part of the sinus venarum of the right atrium, at the upper right front portion of the heart. It is also known as the cranial vena cava in other animals.

No valve divides the superior vena cava from the right atrium. As a result, the (right) atrial and (right) ventricular contractions are conducted up into the internal jugular vein and, through the sternocleidomastoid muscle, can be seen as the jugular venous pressure.

Clinical significance

Superior vena cava obstruction refers to a partial or complete obstruction of the superior vena cava, typically in the context of cancer such as a cancer of the lung, metastatic cancer, or lymphoma. Obstruction can lead to enlarged veins in the head and neck, and may also cause breathlessness, cough, chest pain, and difficulty swallowing. Pemberton's sign may be positive. Tumours causing obstruction may be treated with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy to reduce their effects, and corticosteroids may also be given.[2]

In tricuspid valve regurgitation, these pulsations are very strong.

Additional images

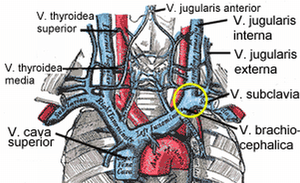

Diagram showing completion of development of the parietal veins.

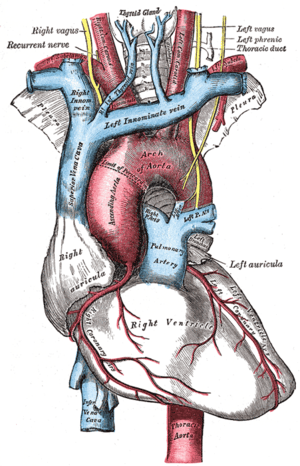

Diagram showing completion of development of the parietal veins. Front view of heart and lungs.

Front view of heart and lungs. Heart seen from above.

Heart seen from above.- Superior vena cava

Transverse section of thorax, showing relations of pulmonary artery.

Transverse section of thorax, showing relations of pulmonary artery. The arch of the aorta and its branches.

The arch of the aorta and its branches. The brachiocephalic veins, superior vena cava, inferior vena cava, azygos vein, and their tributaries.

The brachiocephalic veins, superior vena cava, inferior vena cava, azygos vein, and their tributaries.

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.gpnotebook.co.uk/simplepage.cfm?ID=463077437&linkID=32255&cook=no

- ↑ Britton, the editors Nicki R. Colledge, Brian R. Walker, Stuart H. Ralston ; illustrated by Robert (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine. (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.