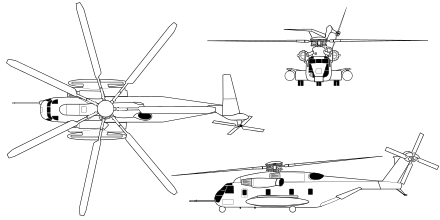

Sikorsky CH-53E Super Stallion

| CH-53E Super Stallion MH-53E Sea Dragon | |

|---|---|

| |

| A CH-53E Super Stallion with the 22nd Marine Expeditionary Unit | |

| Role | Heavy-lift cargo helicopter |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Sikorsky Aircraft |

| First flight | 1 March 1974 |

| Introduction | 1981 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | United States Marine Corps United States Navy Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force |

| Produced | 1978-1980s |

| Number built | 234 |

| Unit cost |

US$24.36 million (1992, avg. cost) |

| Developed from | Sikorsky CH-53 Sea Stallion |

| Developed into | Sikorsky CH-53K King Stallion |

The Sikorsky CH-53E Super Stallion is the largest and heaviest helicopter in the United States military. As the Sikorsky S-80 it was developed from the CH-53 Sea Stallion, mainly by adding a third engine, adding a seventh blade to the main rotor and canting the tail rotor 20 degrees. It was built by Sikorsky Aircraft for the United States Marine Corps. The less common MH-53E Sea Dragon fills the United States Navy's need for long range minesweeping or Airborne Mine Countermeasures (AMCM) missions, and perform heavy-lift duties for the Navy. Under development is the CH-53K King Stallion, which will be equipped with new engines, new composite material rotor blades, and a wider aircraft cabin.

Development

Background

The CH-53 was the product of the U.S. Marines' "Heavy Helicopter Experimental" (HH(X)) competition begun in 1962. Sikorsky's S-65 was selected over Boeing Vertol's modified CH-47 Chinook version. The prototype YCH-53A first flew on 14 October 1964.[1] The helicopter was designated "CH-53A Sea Stallion" and delivery of production helicopters began in 1966.[2] The first CH-53As were powered by two General Electric T64-GE-6 turboshaft engines with 2,850 shp (2,125 kW) and had a maximum gross weight of 46,000 lb (20,865 kg) including 20,000 lb (9,072 kg) in payload.

Variants of the original CH-53A Sea Stallion include the RH-53A/D, HH-53B/C, CH-53D, CH-53G, and MH-53H/J/M. The RH-53A and RH-53D were used by the US Navy for mine sweeping. The CH-53D included a more powerful version of the General Electric T64 engine, used in all H-53 variants, and external fuel tanks. The CH-53G was a version of the CH-53D produced in West Germany for the German Army.[1]

The US Air Force's HH-53B/C "Super Jolly Green Giant" were for special operations and combat rescue and were first deployed during the Vietnam War. The Air Force's MH-53H/J/M Pave Low helicopters were the last of the twin engined H-53s and were equipped with extensive avionics upgrades for all weather operation.

H-53E

In October 1967, the US Marine Corps issued a requirement for a helicopter with a lifting capacity 1.8 times that of the CH-53D that would fit on amphibious warfare ships. The US Navy and US Army were also seeking similar helicopters at the time. Before issue of the requirement Sikorsky had been working on an enhancement to the CH-53D, under the company designation "S-80", featuring a third turboshaft engine and a more powerful rotor system. Sikorsky proposed the S-80 design to the Marines in 1968. The Marines liked the idea since it promised to deliver a good solution quickly, and funded development of a testbed helicopter for evaluation.[3]

In 1970, against pressure by the US Defense Secretary to take the Boeing Vertol XCH-62 being developed for the Army, the Navy and Marines were able to show the Army's helicopter was too large to operate on landing ships and were allowed to pursue their helicopter.[3] Prototype testing investigated the addition of a third engine and a larger rotor system with a seventh blade in the early 1970s. In 1974, the initial YCH-53E first flew.[4]

Changes on the CH-53E also include a stronger transmission and a fuselage stretched 6 feet 2 inches (1.88 m). The main rotor blades were changed to a titanium-fiberglass composite.[3] The tail configuration was also changed. The low-mounted symmetrical horizontal tail was replaced by a larger vertical tail and the tail rotor tilted from the vertical to provide some lift in hover while counteracting the main rotor torque. Also added was a new automatic flight control system.[4] The digital flight control system prevented the pilot from overstressing the aircraft.[3]

YCH-53E testing showed that it could lift 17.8 tons (to a 50-foot (15 m) wheel height), and without an external load, could reach 170 knots (310 km/h) at a 56,000 pound gross weight. This led to two preproduction aircraft and a static test article being ordered. At this time the tail was redesigned to include a high-mounted, horizontal surface opposite the rotor with an inboard section perpendicular to the tail rotor then at the strut connection cants 20 degrees to horizontal.[4]

The initial production contract was awarded in 1978, and service introduction followed in February 1981.[3] The first production CH-53E flew in December 1980.[4] The US Navy acquired the CH-53E in small numbers for shipboard resupply. The Marines and Navy acquired a total of 177.[3]

The Navy requested a version of the CH-53E for the airborne mine countermeasures role, designated "MH-53E Sea Dragon". It has enlarged sponsons to provide substantially greater fuel storage and endurance. It also retained the in-flight refueling probe, and could be fitted with up to seven 300 US gallon (1,136 liter) ferry tanks internally. The MH-53E digital flight-control system includes features specifically designed to help tow minesweeping gear.[3] The prototype MH-53E made its first flight on 23 December 1981. MH-53E was used by the Navy beginning in 1986. The MH-53E is capable of in-flight refueling and can be refueled at hover.[4] The Navy obtained a total of 46 Sea Dragons and is converting the remaining RH-53Ds back to the transport role.[3]

_15_conducts_a_mine_sweeping_exercise.jpg)

Additionally, a number of MH-53E helicopters have been exported to Japan as the S-80-M-1 for the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF).

The base model CH-53E serves both the US Navy and Marines in the heavy lift transport role. It is capable of lifting heavy equipment including the eight-wheeled LAV-25 Light Armored Vehicle, the M198 155 mm Howitzer with ammunition and crew. The Super Stallion can recover aircraft up to its size, which includes all Marine Corps aircraft except for the KC-130.

The pressurized blade spar is a cause of high maintenance, and the 53E needs 40 maintenance hours per flight hour.[5]

CH-53K

The US Marine Corps had been planning to upgrade most of their CH-53Es to keep them in service, but this plan stalled. Sikorsky then proposed a new version, originally the "CH-53X", and in April 2006, the USMC signed a contract for 156 aircraft as the "CH-53K".[6][7] The Marines are planning to start retiring CH-53Es in 2009 and need new helicopters very quickly.[8]

In August 2007, the USMC increased its order of CH-53Ks to 227.[9] First flight was planned for November 2011 with initial operating capability by 2015.[10]

Design

Although dimensionally similar, the three engine CH-53E Super Stallion or Sikorsky S-80 is a much more powerful aircraft than the original Sikorsky S-65 twin engined CH-53A Sea Stallion. The CH-53E also added a larger main rotor system with a seventh blade.

The CH-53E can transport up to 55 troops or 30,000 lb (13,610 kg) of cargo and can carry external slung loads up to 36,000 lb (16,330 kg).[3] The Super Stallion has a cruise speed of 173 mph (278 km/h) and a range of 621 miles (1,000 km).[11] The helicopter is fitted with a forward extendable in-flight refueling probe and it can also hoist hose refuel from a surface ship while in hover mode. It can carry three machine guns: one at the starboard side crew door; one at the port window, just behind the copilot; and one at the tail ramp. The CH-53E also has chaff-flare dispensers.[3]

The MH-53E features enlarged side mounted fuel sponsons and is rigged for towing its mine sweeping "sled" from high above the dangerous naval mines. The Sea Dragon is equipped with mine countermeasures systems, including twin machine guns. Its digital flight-control system includes features specifically designed to help towing mine sweeping gear.[3]

Upgrades to the CH-53E have included the Helicopter Night Vision System (HNVS), improved .50 BMG (12.7 mm) GAU-21/A and M3P machine guns, and AAQ-29A forward looking infrared (FLIR) imager.[3]

The CH-53E and the MH-53E are the largest helicopters in the Western world, while the CH-53K now being developed will be even larger. They are fourth in the world to the Russian Mil Mi-26 Halo single-rotor helicopter and the enormous, twin transverse rotored Mil V-12 Homer, which can lift more than 22 tons (20 tonnes) and 44 tons (40 tonnes), respectively and the Mi-26's single-rotor predecessor Mil Mi-6, which has less payload (12 tonnes) but is bigger and has a higher MTOW at 42 tonnes.

Operational history

_receive_fuel_from_a_KC-130_Hercules.jpg)

1980s

The Super Stallion variant first entered service with the creation of Heavy Marine Helicopter Squadron 464 at Marine Corps Air Station New River, North Carolina. Two more squadrons were created at Marine Corps Air Station Tustin, California over the next several years, HMH-465 and HMH-466. In addition, one west coast training squadron, HMT-301, was given Super Stallions as was one more east coast squadron, HMH-772, out of a reserve base at NASJRB Willow Grove, Pennsylvania. Since then, other Marine Heavy lift squadrons have retired their CH-53As and Ds, replacing them with Es.

The Marine Corps CH-53E saw its first shipboard deployment in 1983 when four CH-53E helicopters from HMH-464 deployed aboard USS Iwo Jima as part of the 24th Marine Amphibious Unit (24th MAU). During this deployment Marines were sent ashore in Beirut, Lebanon as peace keepers and established perimeters at and near the Beirut International Airport. On 23 October 1983 a truck bomb detonated by terrorists destroyed the Marine barracks in Beirut, killing nearly 240 service members as they slept. CH-53E helicopters from the 24th MAU provided critical combat support during this operation.

1990s

In 1991, two CH-53Es along with several CH-46 Sea Knight helicopters were sent to evacuate U.S. and foreign nationals from the U.S. embassy in Mogadishu, Somalia—Operation Eastern Exit—as violence enveloped the city during the Somalian Civil War.[12]

During Operation Desert Storm, MH-53E shipboard based Sea Dragons were used for mine clearing operations in the Persian Gulf off Kuwait.

On 8 June 1995, Captain Scott O'Grady, an F-16 Fighting Falcon pilot shot down over Bosnia, was rescued by two CH-53Es.[13]

2000s

On 26 October 2001 3 CH-53Es aboard USS Peleliu and 3 CH-53Es aboard USS Bataan flew 550 miles (890 km) to secure the first land base in Afghanistan, Camp Rhino, with 1100 troops at its peak.[14] This amphibious raid is the longest amphibious raid in history. The long range capability of the CH-53Es enabled Marines to establish a southern base in Afghanistan, putting the war on the ground.

Super Stallions again played a major role in the 2003 invasion of Iraq. They were critical to moving supplies and ammunition to the most forward Marine units and also assisted in moving casualties back to the rear for follow on care. Marine CH-53Es and CH-46Es carried US Army Rangers and Special Operations troops in a mission to rescue captured Army Private Jessica Lynch on 1 April 2003.[15]

Currently about 150 CH-53E helicopters are in service with the Marines and another 28 MH-53Es are in service with the U.S Navy. The CH-53 requires 44 maintenance hours per flight hour. A flight hour costs about $20,000.[16]

Variants

- YCH-53E

- United States military designation for two Sikorsky S-65E (later S-80E) prototypes.

- CH-53E Super Stallion

- United States military designation for the S-80E heavy lift transport variant for the United States Navy and Marine Corps, 170 built.

- MH-53E Sea Dragon

- United States military designation for the S-80M mine-countermeasures variant for the United States Navy, 50 built.

- VH-53F

- Proposed presidential transport variant, not-built.

- S-80E

- Export variant of the heavy lift transport variant, not-built.

- S-80M

- Export variant of the mine-countermeasures variant, 11-built for Japan.

Operators

_Helicopter_Mine_Squadron_111_land.jpg)

Accidents

Between 1969-1990, more than 200 servicemen had been killed in accidents involving the CH-53A, CH-53D and CH-53E.[29] The MH-53E Sea Dragon is the U.S. Navy's helicopter most prone to accidents, with 27 deaths from 1984 to 2008. During that timeframe its rate of Class A mishaps, meaning serious damage or loss of life, was 5.96 per 100,000 flight hours, more than twice the Navy helicopter average of 2.26.[30] A 2005 lawsuit alleges that since 1993 there were at least 16 in-flight fires or thermal incidents involving the No. 2 engine on Super Stallion helicopters. The suit claims that proper changes were not made, nor were crews instructed on emergency techniques.[31][32]

- On 1 June 1984, a CH-53E based at Tustin was lifting a truck from the deck of a ship during an exercise when a sling attached to the truck broke. This sent a shock wave into the aircraft and caused major damage. Four crew members died in the accident.[33]

- On 19 November 1984, a CH-53E on a routine training mission at Camp Lejeune, NC, was lifting a seven-ton howitzer before it crashed. Six people were killed, and 11 injured.[33] It experienced a loss of tail rotor function, lost control and impacted the ground. The cabin area was quickly consumed by the ensuing fire.[34]

- On 13 July 1985 a CH-53E from a Tustin squadron was on a flight in Okinawa when it struck a logging cable and exploded. Four people were killed.[33]

- On 25 August 1985 a CH-53E from New River, NC, was flying a routine supply and passenger run from Tustin to Twentynine Palms during a training operation when it caught fire and crashed in Laguna Hills. One of the three crew members was killed and the aircraft was a total loss.[33][35]

- On 9 May 1986, a CH-53E crashed during training exercises near Twentynine Palms, killing four Marines and injuring another. The accident was the Super Stallion's fifth crash in two-year period.[36]

- On 8 January 1987, a Marine Corps CH-53E crashed while practicing night landings for troop deployment at the Salton Sea Test Range. All five crew members were killed.[37]

- On 9 May 1996, a CH-53E crashed at Sikorsky's Stratford plant, killing four employees on board. This led to the Navy grounding all CH-53Es and MH-53Es.[31]

- On 10 August 2000, a MH-53E Sea Dragon crashed in the Gulf of Mexico near Corpus Christi and resulted in the deaths of four of the six crew members. The helicopters were later returned to service with improved swash plate duplex bearings and new warning systems for the bearings.[38][39]

- On 20 January 2002, a CH-53E crash in Afghanistan killed two crew members and injured five others. Defense Department officials said the early-morning crash was the result of mechanical problems with the helicopter.[40]

- On 2 April 2002, a Navy MH-53E (BuNo 163051) of HM-14 crashed on the runway at Bahrain International Airport. All 18 people on board survived with only a few cases of minor injuries.[41]

- On 27 June 2002, a Navy MH-53E Sea Dragon of Helicopter Combat Support Squadron 4 (HC-4) "Black Stallions" crashed in a hard landing at NAS Sigonella, Sicily. No one was injured, but the aircraft was written off.[41][42]

- On 16 July 2003, a Navy MH-53E Sea Dragon of Helicopter Combat Support Squadron 4 (HC-4) "Black Stallions" crashed near the town of Palagonia, about 10 miles west-southwest of Naval Air Station Sigonella, killing the four member crew. The flight was on a routine training mission.[42][43]

- On 26 January 2005 a CH-53E carrying 30 Marines and one Navy Corpsman crashed in Rutbah, Iraq, killing all 31 on board.[44][45] A sandstorm was determined as the cause of the accident. The crash was part of the deadliest day of the Iraq War in terms of US fatalities.[46]

- On 16 February 2005, an MH-53E from Helicopter Combat Support Squadron 4 (HC-4), based at Naval Air Station Sigonella, Sicily, crashed on the base, injuring the four crew members.[47]

- On 17 February 2006, two CH-53Es carrying a combined U.S. Marine Corps and Air Force crew collided during a training mission over the Gulf of Aden, resulting in ten deaths and two injuries.[48][49]

- On 16 January 2008, a Navy MH-53E on a routine training mission crashed approximately four miles south of Corpus Christi, Texas. Three crew members died in the crash and one crew member was treated at a local hospital.[50]

- On 29 June 2012, a Navy MH-53E from HM-14 made an emergency landing five miles northeast of Pohang, South Korea due to an in-flight fire. Though the pilots and aircrew were uninjured, the aircraft was heavily damaged by the fire.[51]

- On 19 July 2012 a Navy MH-53E crashed 58 miles south of Muscat, Oman during a heavy lift operation, resulting in two deaths.[52]

- On 8 January 2014, a US Navy MH-53E Sea Dragon crashed in the Atlantic 18 nautical miles east of Cape Henry, Virginia with five crew members on board. Three crew members perished in the mishap.[53][54][55]

- On 1 September 2014, a US Marine CH-53E of the 22nd Marine Expeditionary Unit crashed in the Gulf of Aden while attempting to land on the USS Mesa Verde following training operations in Djibouti. All 17 Marines and 8 sailors on board were rescued.[56]

- On 14 January 2016, two US Marine CH-53Es conducting a night time training exercise off the coast of Hawaii collided with each other, resulting in a total hull loss of both ships. Each CH-53E had a crew of six on board at the time.[57]

Specifications (CH-53E)

_15%2C_performs_mine_countermeasure_training_using_the_MK-105_sled.jpg)

Data from U.S. Navy history,[58] International Directory,[2] World Aircraft[59]

General characteristics

- Crew: 5: 2 pilots, 1 crew chief/right gunner, 1 left gunner, 1 tail gunner (combat crew)

- Capacity: 37 troops (55 with centerline seats installed)

- Payload: internal: 30,000 lb or 13,600 kg (external: 36,000 lb or 14,500 kg)

- Length: 99 ft 1/2 in (30.2 m)

- Rotor diameter: 79 ft (24 m)

- Height: 27 ft 9 in (8.46 m)

- Disc area: 4,900 ft² (460 m²)

- Empty weight: 33,226 lb (15,071 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 73,500 lb (33,300 kg)

- Rotor systems: 7 blades on main rotor, 4 blades on anti-torque tail rotor

- Powerplant: 3 × General Electric T64-GE-416/416A turboshaft, 4,380 shp[60] (3,270 kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 170 knots (196 mph, 315 km/h)

- Cruise speed: 150 kt (173 mph, 278 km/h)

- Range: 540 nmi (621 mi, 1,000 km)

- Ferry range: 990 nmi (1,139 mi, 1,833 km)

- Service ceiling: 18,500 ft (5,640 m)

- Rate of climb: 2,500 ft/min (13 m/s)

Armament

- Guns:

- 2× .50 BMG (12.7 x 99 mm) window-mounted GAU-15/A machine guns

- 1× .50 BMG (12.7 x 99 mm) ramp mounted weapons system, GAU-21 (M3M mounted machine gun)

- Other: Chaff and flare dispensers

Notable appearances in media

See also

- Related development

- HH-53 "Super Jolly Green Giant"/MH-53 Pave Low

- Sikorsky CH-53 Sea Stallion

- Sikorsky CH-53K King Stallion

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

References

- 1 2 Sikorsky Giant Helicopters: S-64, S-65, & S-80, Vectorsite.net, 1 December 2009.

- 1 2 Frawley, Gerard. The International Directory of Military Aircraft, p. 148. Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd, 2002. ISBN 1-875671-55-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 S-80 Origins / US Marine & Navy Service / Japanese Service. Vectorsite.net, 1 December 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "CH-53A/D/E Sea Stallion AND MH-53E Sea Dragon". US Navy, 15 November 2000.

- ↑ Head, Elan (2017). "Meet the King". p. 47. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ↑ "Sikorsky Awarded $3.0B Development Contract For Marine Corps CH-53K Heavy-Lift Helicopter". Sikorsky Aircraft, 5 April 2006.

- ↑ "Sikorsky Aircraft Marks Start of CH-53K Development and Demonstration Phase". Sikorsky Aircraft, 17 April 2006.

- ↑ S-80 Upgrades / CH-53K. Vectorsite.net, 1 December 2009.

- ↑ "Marines Up Order for New Heavy Lifter", "Rotor & Wing", 1 August 2007.

- ↑ "US Marines in desperate need of new CH-53K". Flight Daily News, 21 June 2007.

- ↑ CH-53D/E page. USMC. Accessed 3 November 2007.

- ↑ Siegel, Adam (October 1991). "Eastern Exit: The Noncombatant Evacuation Operation (NEO) From Mogadishu, Somalia in January 1991" (PDF). Center for Naval Analyses. Alexandria, Virginia: Center for Naval Analyses. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ↑ CH-53E Super Stallion article. Globalsecurity.org

- ↑ Statement of Admiral Vern Clark, before the Senate Armed Services Committee, 25 February 2003. Navy.mil

- ↑ Stout, Jay A. Hammer from Above, Marine Air Combat Over Iraq. Ballantine Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0-89141-871-9.

- ↑ Whittle, Richard. USMC CH-53E Costs Rise With Op Tempo Rotor & Wing, Aviation Today, January 2007. Accessed: 15 March 2012. Quote: For every hour the Corps flies a -53E, it spends 44 maintenance hours fixing it. Every hour a Super Stallion flies it costs about $20,000.

- 1 2 3 "World Air Forces 2013" (PDF). Flightglobal Insight. 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "Squadron HMH-361". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "HMH-366 Crew chief from Cherry Point reaches milestone". marines.mil. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "Squadron HMH-461". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "Squadron HMH-462". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "Squadron HMH-464". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron 465". marines.mil. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "HMH-466 "Wolfpack"". tripod.com. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "Squadron HMH-769". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "Squadron HMH-772". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "Helicopter Combat Support Squadron 14". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "Helicopter Combat Support Squadron 15". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "Helicopter Crash Kills 1 Marine, Injures 5". Retrieved 8 Jun 2012.

- ↑ "MH-53 twice as crash-prone as other copters". Navy Times. Associated Press. 21 January 2008.

- 1 2 "Suit blames Sikorsky, GE in air crash". koskoff.com, 16 July 2005.

- ↑ "Sikorsky, We Have A Problem". ctnewsjunkie.com, 2 August 2005.

- 1 2 3 4 "A History of CH-53E Incidents". 15 February 1987. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ↑ "Brothers Killed in Action in USMC Helicopters".

- ↑ "Laguna Hills Helicopter Crash Kills 1, Injures 4 : Marine Super Stallion Ignites One-Acre Grass Fire When It Goes Down in Field". Retrieved 8 Jun 2012.

- ↑ "Officials Identify Marines Killed, Hurt in Twentynine Palms Helicopter Crash". Retrieved 8 Jun 2012.

- ↑ "Marine Copter Crashes; All 5 on Board Die". Retrieved 8 Jun 2012.

- ↑ Sherman, Christopher. "Copter in crash has spotty record". Associated Press via theeagle.com, 19 January 2008.

- ↑ "Copters airborne after grounding". Amarillo Globe-News. Retrieved 2015-10-09.

- ↑ "Copter Crash Deals Another Blow to San Diego Marines". Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- 1 2 "US Navy and US Marine Corps BuNos". joebaugher.com.

- 1 2 "Victims of Sigonella crash found". Stars and Stripes.

- ↑ "Sigonella pays tribute to four victims of Sea Dragon crash". Stars and Stripes.

- ↑ "Worst US air losses in Iraq". The Telegraph, 22 August 2007.

- ↑ "Iraq air crash kills 31 US troops". BBC, 26 January 2005.

- ↑ "Deadliest day for U.S. in Iraq war". CNN, 27 January 2005.

- ↑ http://www.navy.mil/search/print.asp?story_id=17138&VIRIN=12604&imagetype=1&page=1.

- ↑ "10 U.S. troops accounted for after crash off Djibouti". The Arizona Republic. 19 February 2006. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ↑ "Combined Joint Task Force — Horn of Africa members honor fallen brethren". Defense Video & Imagery Distribution System. 13 November 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ↑ "MH-53E Sea Dragon Crashes South of Corpus Christi". US Navy, 17 January 2008.

- ↑ "Navy MH-53 Helicopter Makes Emergency Landing". US Navy, 29 June 2012.

- ↑ "MH-53 Helicopter Suffers Aviation Mishap, Crashes". US Navy, 19 July 2012.

- ↑ "1 still missing in Navy copter crash that killed 2". MSN News. Associated Press. 9 January 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ↑ Lewis, Paul (8 January 2014). "US navy helicopter goes down off Virginia coast". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ↑ U.S. News (27 September 2015). "Two crewmen dead after Navy helicopter goes down off Va.; one missing". NBC News.

- ↑ "U.S. military personnel rescued at sea after helicopter crash near Djibouti". CNN. CNN. 1 September 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ↑ "Helicopter crash in Hawaii: Search for 12 missing Marines - CNN.com". CNN. Retrieved 2016-01-16.

- ↑ CH-53A/D/E Sea Stallion and MH-53E Sea Dragon, US Navy.

- ↑ Donald, David ed. "Sikorsky S-65", The Complete Encyclopedia of World Aircraft. Barnes & Nobel Books, 1997. ISBN 0-7607-0592-5.

- ↑ "About the GE T64" BGA-aeroweb, May 17, 2012. Accessed: April 10, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sikorsky CH-53E Super Stallion. |

- CH-53/MH-53E history, CH-53E, and MH-53E pages on Navy.mil

- CH-53D/E page on USMC.mil

- CH-53E/S-80E page and MH-53E page on Sikorsky.com

- HELIS.com Sikorsky S-80/H-53E Super Stallion Database

- The History of Heavy Lift: Can the 1947 Vision of an All Heavy Helicopter Force Achieve Fruition in 2002?

- CH-53E and MH-53E pages on GlobalSecurity.org

- Vertical Envelopment and the Future Transport Rotorcraft, RAND