Super-Kamiokande

| Beyond the Standard Model |

|---|

Simulated Large Hadron Collider CMS particle detector data depicting a Higgs boson produced by colliding protons decaying into hadron jets and electrons |

| Standard Model |

Coordinates: 36°25′32.6″N 137°18′37.1″E / 36.425722°N 137.310306°E[1]

Super-Kamiokande (full name: Super-Kamioka Neutrino Detection Experiment, abbreviated to Super-K or SK; Japanese: スーパーカミオカンデ) is a neutrino observatory located under Mount Ikeno near the city of Hida, Gifu Prefecture, Japan. The observatory was designed to search for proton decay, study solar and atmospheric neutrinos, and keep watch for supernovae in the Milky Way Galaxy.

Description

The Super-K is located 1,000 m (3,300 ft) underground in the Mozumi Mine in Hida's Kamioka area. It consists of a cylindrical stainless steel tank that is 41.4 m (136 ft) tall and 39.3 m (129 ft) in diameter holding 50,000 tons of ultra-pure water. The tank volume is divided by a stainless steel superstructure into an inner detector (ID) region that is 33.8 m (111 ft) in diameter and 36.2 m (119 ft) in height and outer detector (OD) which consists of the remaining tank volume. Mounted on the superstructure are 11,146 photomultiplier tubes (PMT) 50 cm (20 in) in diameter that face the ID and 1,885 20 cm (8 in) PMTs that face the OD. There is a Tyvek and blacksheet barrier attached to the superstructure that optically separates the ID and OD.

A neutrino interaction with the electrons or nuclei of water can produce a charged particle that moves faster than the speed of light in water (not to be confused with exceeding the speed of light in a vacuum). This creates a cone of light known as Cherenkov radiation, which is the optical equivalent to a sonic boom. The Cherenkov light is projected as a ring on the wall of the detector and recorded by the PMTs. Using the timing and charge information recorded by each PMT, the interaction vertex, ring direction and flavor of the incoming neutrino is determined. From the sharpness of the edge of the ring the type of particle can be inferred. The multiple scattering of electrons is large, so electromagnetic showers produce fuzzy rings. Highly relativistic muons, in contrast, travel almost straight through the detector and produce rings with sharp edges.

Detector

The Super-Kamiokande (SK) is a Cherenkov detector used to study neutrinos from different sources including the Sun, supernovae, the atmosphere, and accelerators for proton decay. The experiment began in April 1996 and was shut down for maintenance in July 2001, a period known as "SK-I". Since an accident occurred during maintenance, the experiment resumed in October 2002 with only half of its original number of ID-PMTs. In order to prevent further accidents, all of the ID-PMTs were covered by fiber-reinforced plastic with acrylic front windows. This phase from October 2002 to another closure for an entire reconstruction in October 2005 is called "SK-II". In July 2006, the experiment resumed with the full number of PMTs and stopped in September 2008 for electronics upgrades. This period was known as "SK-III". The period after 2008 is known as "SK-IV". The phases and their main characteristics are summarised in table 1.[2]

| Phase | SK-I | SK-II | SK-III | SK-IV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Start | 1996 Apr. | 2002 Oct. | 2006 Jul. | 2008 Sep. |

| End | 2001 Jul. | 2005 Oct. | 2008 Sep. | (running) | |

| Number of PMTs | ID | 11146 (40%) | 5182 (19%) | 11129 (40%) | 11129 (40%) |

| OD | 1885 | ||||

| Anti-implosion container | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| OD segmentation | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Front-end electronics | ATM (ID) | QBEE | |||

| OD QTC (OD) | |||||

SK-IV upgrade

In the previous phases, the ID-PMTs processed signals by custom electronics modules called analog timing modules (ATMs). Charge-to-analog converters (QAC) and time-to-analog converters (TAC) are contained in these modules that had dynamic range from 0 to 450 picocoulombs (pC) with 0.2 pC resolution for charge and from −300 to 1000 ns with 0.4 ns resolution for time. There were two pairs of QAC/TAC for each PMT input signal, this prevented dead time and allowed the readout of multiple sequential hits that may arise, e.g. from electrons that are decay products of stopping muons.[3]

The SK system was upgraded in September 2008 in order to maintain the stability in the next decade and improve the throughput of the data acquisition systems, QTC-based electronics with Ethernet (QBEE).[4] The QBEE provides high-speed signal processing by combining pipelined components. These components are a newly developed custom charge-to-time converter (QTC) in the form of an application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC), a multi-hit time-to-digital converter (TDC), and field-programmable gate array (FPGA).[5] Each QTC input has three gain ranges – “Small”, “Medium” and “Large” – the resolutions for each are shown in Table.[6]

| Range | Measuring region | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Small | 0–51 pC | 0.1 pC/count (0.04 pe/count) |

| Medium | 0–357 pC | 0.7 pC/count (0.26 pe/count) |

| Large | 0–2500 pC | 4.9 pC/count (1.8 pe/count) |

For each range, analog to digital conversion is conducted separately, but the only range used is that with the highest resolution that is not being saturated. The overall charge dynamic range of the QTC is 0.2–2500 pC, five times larger than the old . The charge and timing resolution of the QBEE at the single photoelectron level is 0.1 photoelectrons and 0.3 ns respectively, both are better than the intrinsic resolution of the 20-in. PMTs used in SK. The QBEE achieves good charge linearity over a wide dynamic range. The integrated charge linearity of the electronics is better than 1%. The thresholds of the discriminators in the QTC are set to −0.69 mV (equivalent to 0.25 photoelectron, which is the same as for SK-III). This threshold was chosen to replicate the behavior of the detector during its previous ATM-based phases.[7]

Water tank

The outer shell of the water tank is a cylindrical stainless-steel tank 39 m in diameter and 42 m in height. The tank is self-supporting, with concrete backfilled against the rough-hewn stone walls to counteract water pressure when the tank is filled. The capacity of the tank exceeds 50 ktons of water.[8]

PMTs and associate structure

The basic unit for the ID PMTs is a “supermodule”, a frame which supports a 3×4 array of PMTs. Supermodule frames are 2.1 m in height, 2.8 m in width and 0.55 m in thickness. These frames are connected to each other in both the vertical and horizontal directions. Then the whole support structure is connected to the bottom of the tank and to the top structure. In addition to serving as rigid structural elements, supermodules simplified the initial assembly of the ID. Each supermodule was assembled on the tank floor and then hoisted into its final position. Thus the ID is in effect tiled with supermodules. During installation, ID PMTs were pre-assembled in units of three for easy installation. Each supermodule has two OD PMTs attached on its back side. The support structure for the bottom PMTs is attached to the bottom of the stainless-steel tank by one vertical beam per supermodule frame. The support structure for the top of the tank is also used as the support structure for the top PMTs.

Cables from each group of 3 PMTs are bundled together. All cables run up the outer surface of the PMT support structure, i.e., on the OD PMT plane, pass through cable ports at the top of the tank, and are then routed into the electronics huts.

The thickness of the OD varies slightly, but is on average about 2.6 m on top and bottom, and 2.7 m on the barrel wall, giving the OD a total mass of 18 ktons. OD PMTs were distributed with 302 on the top layer, 308 on the bottom, and 1275 on the barrel wall.

To protect against low energy background from radon decay products in the air, the roof of the cavity and the access tunnels were sealed with a coating called Mineguard® produced by Urylon in Canada. Mineguard® is a spray-applied polyurethane membrane developed for use as a rock support system and radon gas barrier in the mining industry.[9]

The average geomagnetic field is about 450 mG and is inclined by about 45° with respect to the horizon at the detector site. This presents a problem for the large and very sensitive PMTs which prefer a much lower ambient field. The strength and uniform direction of the geomagnetic field could systematically bias photoelectron trajectories and timing in the PMTs. To counteract this 26 sets of horizontal and vertical Helmholtz coils are arranged around the inner surfaces of the tank. With these in operation the average field in the detector is reduced to about 50 mG. The magnetic field at various PMT locations were measured before the tank was filled with water.[10]

A standard fiducial volume of approximately 22.5 ktons is defined as the region inside a surface drawn 2.00 m from the ID wall to minimize the anomalous response causing by natural radioactivity in the surrounding rock.

Monitoring system

Online monitoring system

An online monitor computer located in the control room reads data from the DAQ host computer via an FDDI link. It provides shift operators with a flexible tool for selecting event display features, makes online and recent-history histograms to monitor detector performance, and performs a variety of additional tasks needed to efficiently monitor status and diagnose detector and DAQ problems. Events in the data stream can be skimmed off and elementary analysis tools can be applied to check data quality during calibrations or after changes in hardware or online software.[11]

Realtime supernova monitor

To detect and identify such bursts as efficiently and promptly as possible Super-Kamiokande is equipped with an online supernova monitor system. About 10,000 total events are expected in Super-Kamiokande for a supernova explosion at the center of our Galaxy. Super-Kamiokande can measure a burst with no dead-time, up to 30,000 events within the first second of a burst. Theoretical calculations of supernova explosions suggest that neutrinos are emitted over a total time-scale of tens of seconds with about a half of them emitted during the first one or two seconds. The Super-K will search for event clusters in specified time windows of 0.5, 2 and 10 s.[12] Data are transmitted to realtime SN-watch analysis process every 2 min and analysis is completed typically in 1 min. When supernova (SN) event candidates are found, is calculated if the event multiplicity is larger than 16, where is defined as the average spatial distance between events, i.e.

Neutrinos from supernovae interact with free protons, producing positrons which are distributed so uniformly in the detector that for SN events should be significantly larger than for ordinary spatial clusters of events. In the Super-Kamiokande detector, Rmean for uniformly distributed Monte Carlo events shows that no tail exists below ⩽1000 cm. For the “alarm” class of burst, the events are required to have ⩾900 cm for 25⩽⩽40 or ⩾750 cm for >40. These thresholds were determined by extrapolation from SN1987A data.[13][14] The system will run special processes to check for spallation muons when burst candidates meeting “alarm” criteria and make a primarily decision for further process. If the burst candidate passes these checks, the data will be reanalyzed using an offline process and a final decision will be made within a few hours. During the Super-Kamiokande I running, this never occurred. One of the important capabilities for [Super-Kamiokande] is to reconstruct the direction to supernova. By neutrino–electron scattering, , a total of 100–150 events are expected in case of a supernova at the center of our Galaxy.[15] The direction to supernova can be measured with angular resolution

where N is the number of events produced by the ν–e scattering. The angular resolution, therefore, can be as good as δθ∼3° for a supernova at the center of our Galaxy.[16] In this case, not only time profile and the energy spectrum of a neutrino burst, but also the information on direction of supernova can be provided.

Slow control monitor and offline process monitor

There is a process called the “slow control” monitor, as part of the online monitoring system, watches the status of the HV systems, the temperatures of electronics crates and the status of the compensating coils used to cancel the geomagnetic field. When any deviation from norms is detected, it will alert physicists to prompt to investigate, take appropriate action, or notify experts.[17]

To monitor and control the offline processes that analyze and transfer data, a set of software was sophisticatedly developed. This monitor allows non-expert shift physicists to identify and repair common problems to minimize down time, and the software package was a significant contribution to the smooth operation of the experiment and its overall high lifetime efficiency for data taking.[18]

Research

Solar neutrino

The energy of Sun comes from the nuclear fusion in its core where a helium atom and an electron neutrino are generated by 4 protons. These neutrinos emitted from this reaction are called solar neutrinos. Photons, created by the nuclear fusion in the center of the Sun, take millions of years to reach the surface; on the other hand, solar neutrinos arrive at the earth in eight minutes due to their lack of interactions with matter. Hence, solar neutrinos make it possible for us to observe the inner Sun in "real-time" that takes millions of years for visible light.[19]

In 1999, the Super-Kamiokande detected strong evidence of neutrino oscillation that successfully explained the solar neutrino problem. The Sun and about 80% of the visible stars produce their energy by the conversion of hydrogen to helium via

Consequently, stars are a source of neutrinos including our Sun. These neutrinos primarily come through the pp-chain in lower masses, and for cooler stars, primarily through CNO-chains of heavier masses.

In the early 1990s, particularly with the uncertainties that accompanied the initial results from Kamioka II and the Ga experiments, no individual experiment required a non-astrophysical solution of the solar neutrino problem. But in aggregate, the Cl, Kamioka II, and Ga experiments indicated a pattern of neutrino fluxes that was not compatible with any adjustment of the SSM. This in turn helped motivate a new generation of spectacularly capable active detectors. These experiments are Super-Kamiokande, the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory (SNO), and Borexino. Super-Kamiokande was able to detect elastic scattering (ES) events

which, due to the charged-current contribution to scattering, has a relative sensitivity to s and heavy-flavor neutrinos of ∼7:1.[20] Since the direction of the recoil electron is constrained to be very forward, the direction of the neutrinos are kept in the direction of recoil electrons. Here, is provided where is the angle between the direction of recoil electrons and the Sun's position. This shows that the solar neutrino flux can be calculated to be . Comparing to the SSM, the ratio is .[21] The result clearly indicates the deficit of solar neutrinos.

Atmospheric neutrino

Atmospheric neutrinos are secondary cosmic rays produced by the decay of particles resulting from interactions of primary cosmic rays (mostly proton) with Earth atmosphere. We classified the observed atmospheric neutrino data into four types. Fully contained (FC) events have all their tracks in the inner detector while partially contained (PC) events have escaping tracks from the inner detector. Upward through-going muons (UTM) are produced in the rock beneath the detector and go through the inner detector. Upward stopping muons (USM) are also produced in the rock beneath the detector but stop in the inner detector.

The number of observed number of neutrinos is predicted uniformly regardless the zenith angle. However, Super-Kamiokande found that the number of upward going muon neutrinos (generated on the other side of the Earth) is half of the number of downward going muon neutrinos in 1998. This can be explained that neutrinos changes or oscillated into some other neutrinos that are not detected. This is called neutrino oscillation and this discovery indicates the finite mass of neutrinos and suggests to extend the Standard Model. Neutrinos oscillate in three flavors and all neutrinos have their rest mass. Later analysis in 2004 suggested a sinsinusoidal dependence of the event rate as a function of “Length/Energy”, which confirmed the neutrino oscillations.[22]

K2K Experiment

The K2K experiment was a neutrino experiment from June 1999 to November 2004. This experiment was designed to verify oscillations observed by Super-Kamiokande through muon neutrinos. It gives first positive measurement of neutrino oscillations in conditions that both source and detector are under control. The Super-Kamiokande detector plays an important role in the experiment as the far detector. Later experiment T2K experiment continued as the second generation follow up to the K2K experiment.

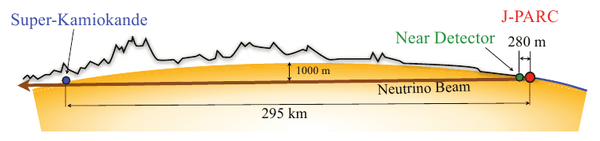

T2K Experiment

T2K (Tokai to Kamioka) experiment is a neutrino experiment collaborated by several countries including Japan, United States and others. The goal of T2K is to gain deeper understanding of parameters of neutrino oscillation. T2K has made a search for oscillations from muon neutrinos to electron neutrinos, and announced the first experimental indications for them in June 2011.[23] The Super-Kamiokande detector plays as the "far detector". The Super-K detector will record the Cherenkov radiation of muons and electrons created by interactions between high energy neutrinos and water.

Proton Decay

Proton is assumed to be absolutely stable in Standard Model. However, the Grand Unified Theories (GUTs) predict that can decay into lighter energetic charged particles such as electrons, muons, pions or others which can be observed. Kamiokande helps to rule out some of the theories. Super-Kamiokande is currently the largest detector for observation of proton decay.

Purification

Water purification system

The 50 ktons pure water is continually reprocessed at rate about 30 tons/h in a close system since early 2002. Now, raw mine water is recycled through the first step (particle filters and RO) for some time before other processes, which involve expensive expendables, are imposed. Initially, water from the Super-Kamiokande tank is passed through nominal 1 μm mesh filters to remove dust and particles, which reduce the transparency of the water for Cherenkov photons, and provide a possible radon source inside the Super-Kamiokande detector. Heat exchanger is used to cool down the water in order to reduce the PMT dark noise level as well as suppress the growth of bacteria. Surviving bacteria are killed by UV sterilizer stage. A cartridge polisher (CP) eliminates heavy ions which also reduce water transparency and include radioactive species. The CP module increases the typical resistivity of recirculating water from 11MΩ cm to 18.24 MΩ cm, approaching chemical limit.[24] Originally, ion-exchanger (IE) was included in system, but it was removed when IE resin was found to be a significant radon source. The RO step that removes additional particulates, and the introduction of Rn-reduced air into the water that increases radon removal efficiency in the vacuum degasifier (VD) stage which follows were installed in 1999. After that, a VD removes dissolved gases in the water. These gases are dissolved in water with a serious background of events source for solar neutrinos in the MeV energy range and the dissolved oxygen encourages the growth of bacteria. The removing efficiency of removing is about 96%. Then, the ultra filter (UF) is introduced to remove particles whose minimum size corresponds to molecular weight approximately 10,000 (or about 10 nm diameter) thanks to hollow fiber membrane filters. Finally, a membrane degasifier (MD) removes radon dissolved in water, and the measured removal efficiency for radon is about 83%. The concentration of radon gases is miniaturized by realtime detectors. In June, 2001 typical radon concentrations in water coming into the purification system from the Super-Kamiokande tank were <2 mBq m−3, and in water output by the system, 0.4±0.2 mBq m−3.[25]

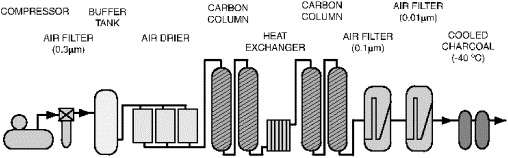

Air purification system

Purified Air is supplied in the gap between the water surface and the top of the Super-Kamiokande tank. The air purification system contains three compressors, a buffer tank, dryers, filters, and activated charcoal filters. A total of 8 m3 of activated charcoal is used. The last 50 L of charcoal is cooled to −40 °C to increase removal efficiency for radon. Typical flow rates, dew point, and residual radon concentration are 18 m3/h, −65 °C (@+1 kg/cm2), and a few mBq m−3, respectively. Typical radon concentration in the dome air is measured to be 40 Bq m−3. Radon levels in the mine tunnel air, near the tank cavity dome, typically reach 2000–3000 Bq m−3 during the warm season, from May until October, while from November to April the radon level is approximately 100–300 Bq m−3. This variation is due to the chimney effect in the ventilation pattern of the mine tunnel system; in cold seasons, fresh air flows into the Atotsu tunnel entrance that is a relatively short path through exposed rock before reaching the experimental area, while in the summer, air flows out the tunnel, drawing radon-rich air from deep within the mine past the experimental area.[26]

In order to keep radon levels in the dome area and water purification system below 100 Bq m−3, fresh air is continually pumped at approximately 10 m3/min from outside the mine which generates a slight over-pressure in the Super-Kamiokande experimental area to minimize the entry of ambient mine air. A “Radon Hut” (Rn Hut) was constructed near the Atotsu tunnel entrance to house equipment for the dome air system: a 40 hp air pump with 10 m^3 min−1 /15 PSI pump capacity, air dehumidifier, carbon filter tanks, and control electronics. In autumn 1997, an extended intake air pipe was installed at a location approximately 25 m above the Atotsu tunnel entrance. This low level satisfies that goals of air quality so that carbon filter regeneration operations would no longer be required.[27]

Data processing

Offline data processing is produced both in Kamioka and United States.

In Kamioka

The offline data processing system is located in Kenkyuto and is connected to Super-Kamiokande detector with 4 km FDDI optical fiber link. Data flow from online system is 450 kbytes s−1 on average, corresponding to 40 Gbytes day−1 or 14 Tbytes yr−1. Magnetic tapes are used in offline system to store data and most of the analysis is accomplished here. The offline processing system is designed platform-independent because different computer architectures are used for data analysis. Because of this, the data structures are based on ZEBRA bank system developed in CERN as well as the ZEBRA exchange system.[28]

Event data from Super-Kamiokande online DAQ system basically contains a list of number of hit PMT, TDC and ADC counts, GPS time-stamps and other housekeeping data. For solar neutrino analysis, lowering the energy threshold is a constant goal, so it is a continual effort to improve the efficiency of reduction algorithms; however, changes in calibrations or reduction methods require reprocessing of earlier data. Typically, 10 Tbytes of raw data is processed every month so that a large amount of CPU power and high-speed I/O access to the raw data. In addition, extensive Monte Carlo simulation processing is also necessary.[29]

Offline system was designed to meet demand of all these: tape storage of a large database (14 Tbytes yr−1), stable semi-realtime processing, nearly continuous re-processing and Monte Carlo simulation. The computer system consists of 3 major sub-systems: the data server, the CPU farm and the network at the end of Run I.[30]

In US

A system dedicated to offsite offline data processing was set up at the Stony Brook University in Stony Brook, NY to process raw data sent from Kamioka. Most of the reformatted raw data is copied from system facility in Kamioka. At Stony Brook, a system was set up for analysis and further processing. At Stony Brook the raw data were processed with a multi-tape DLT drive. The first stage data reduction processes were done for the high energy analysis and for the low energy analysis. The data reduction for the high energy analysis was mainly for atmospheric neutrino events and proton decay search while the low energy analysis was mainly for the solar neutrino events. The reduced data for the high energy analysis was further filtered by other reduction processes and the resulting data were stored on disks. The reduced data for the low energy were stored on DLT tapes and sent to University of California, Irvine for further processing.

This offset analysis system continued for 3 years until their analysis chains were proved to produce equivalent results. Thus, in order to limited manpower, collaborations were concentrated to single combined analysis[31]

History

Construction of the predecessor of the present Kamioka Observatory, the Institute for Cosmic Ray Research, University of Tokyo began in 1982 and was completed in April, 1983. The purpose of the observatory was to detect whether proton decay exists, one of the most fundamental questions of elementary particle physics.[32][33][34][35][36]

The detector, named KamiokaNDE for Kamioka Nucleon Decay Experiment, was a tank 16.0 m (52 ft) in height and 15.6 m (51.2 ft) in width, containing 3,048 metric tons (3,000 tons) of pure water and about 1,000 photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) attached to its inner surface. The detector was upgraded, starting in 1985, to allow it to observe solar neutrinos. As a result, the detector (KamiokaNDE-II) had become sensitive enough to detect neutrinos from SN 1987A, a supernova which was observed in the Large Magellanic Cloud in February 1987, and to observe solar neutrinos in 1988. The ability of the Kamiokande experiment to observe the direction of electrons produced in solar neutrino interactions allowed experimenters to directly demonstrate for the first time that the sun was a source of neutrinos.

The Super-Kamiokande project was approved by the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture in 1991 for total funding of approximately $100 M. The US portion of the proposal, which was primarily to build the OD system, was approved by the US Department of Energy in 1993 for $3 M. In addition the US has also contributed about 2000 20 cm PMTs recycled from the IMB experiment.[37]

Despite successes in neutrino astronomy and neutrino astrophysics, Kamiokande did not achieve its primary goal, the detection of proton decay. Higher sensitivity was also necessary to obtain high statistical confidence in its results. This led to the construction of Super-Kamiokande, with fifteen times the water and ten times as many PMTs as Kamiokande. Super-Kamiokande started operation in 1996.

The Super-Kamiokande Collaboration announced the first evidence of neutrino oscillation in 1998.[38] This was the first experimental observation supporting the theory that the neutrino has non-zero mass, a possibility that theorists had speculated about for years.

On November 12, 2001, about 6,600 of the photomultiplier tubes (costing about $3000 each[39]) in the Super-Kamiokande detector imploded, apparently in a chain reaction or cascading failure, as the shock wave from the concussion of each imploding tube cracked its neighbours. The detector was partially restored by redistributing the photomultiplier tubes which did not implode, and by adding protective acrylic shells that are hoped will prevent another chain reaction from recurring (Super-Kamiokande-II).

In July 2005, preparations began to restore the detector to its original form by reinstalling about 6,000 PMTs. The work was completed in June 2006, whereupon the detector was renamed Super-Kamiokande-III. This phase of the experiment collected data from October 2006 till August 2008. At that time, significant upgrades were made to the electronics. After the upgrade, the new phase of the experiment has been referred to as Super-Kamiokande-IV. SK-IV continues to run*, collecting data on various natural sources of neutrinos, as well as acting as the far detector for the Tokai-to-Kamioka (T2K) long baseline neutrino oscillation experiment.

Results

In 1998, Super-K found first strong evidence of neutrino oscillation from the observation of muon neutrinos changed into tau-neutrinos.[40]

SK has set limits on proton lifetime and other rare decays and neutrino properties. SK set a lower bound on protons decaying to kaons of 5.9 × 1033 yr[41]

In popular culture

Super-Kamiokande is the subject of German photographer Andreas Gursky's 2007 image, Kamiokande.[42] The detector was a topic in the television series Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey.

See also

- Masatoshi Koshiba

- Yoji Totsuka

- Takaaki Kajita

- Supernova 1987A

- Solar neutrino problem

- Sudbury Neutrino Observatory

- K2K experiment

- T2K experiment

References

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 501 (2–3): 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ K. Abe; et al. (11 February 2014), "Calibration of the Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 737: 253–272, Bibcode:2014NIMPA.737..253A, arXiv:1307.0162

, doi:10.1016/j.nima.2013.11.081

, doi:10.1016/j.nima.2013.11.081 - ↑ K. Abe; et al. (11 February 2014), "Calibration of the Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 737: 253–272, Bibcode:2014NIMPA.737..253A, arXiv:1307.0162

, doi:10.1016/j.nima.2013.11.081

, doi:10.1016/j.nima.2013.11.081 - ↑ S. Yamada; et al. (2009), IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science, NS-57: 248 Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ H. Nishino; et al. (2009), "High-speed charge-to-time converter ASIC for the Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 610: 710–717, Bibcode:2009NIMPA.610..710N, arXiv:0911.0986

, doi:10.1016/j.nima.2009.09.026

, doi:10.1016/j.nima.2009.09.026 - ↑ K. Abe; et al. (11 February 2014), "Calibration of the Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 737: 253–272, Bibcode:2014NIMPA.737..253A, arXiv:1307.0162

, doi:10.1016/j.nima.2013.11.081

, doi:10.1016/j.nima.2013.11.081 - ↑ K. Abe; et al. (11 February 2014), "Calibration of the Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 737: 253–272, Bibcode:2014NIMPA.737..253A, arXiv:1307.0162

, doi:10.1016/j.nima.2013.11.081

, doi:10.1016/j.nima.2013.11.081 - ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ Hirata, K; et al. (6 April 1987), "Observation of a neutrino burst from the supernova SN1987A", Physical Review Letters, 58 (14): 1490–1493, Bibcode:1987PhRvL..58.1490H, PMID 10034450, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.58.1490

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ The official Super-Kamiokande home page/research

- ↑ A.B. Balantekin; et al. (July 2013), "Neutrino oscillations", Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics, 71: 150–161, Bibcode:2013PrPNP..71..150B, arXiv:1303.2272

, doi:10.1016/j.ppnp.2013.03.007

, doi:10.1016/j.ppnp.2013.03.007 - ↑ J.N Bahcall; S Basu; M.H Pinsonneault (1998), "How uncertain are solar neutrino predictions?", Physics Letters B, 433: 1–8, Bibcode:1998PhLB..433....1B, arXiv:astro-ph/9805135

, doi:10.1016/S0370-2693(98)00657-1

, doi:10.1016/S0370-2693(98)00657-1 - ↑ The Super-Kamiokande Homepage

- ↑ The official homepage of T2K experiment

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande Detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 501: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ The official Super-Kamiokande home page

- ↑ American Super-K home page

- ↑ Pictures and illustrations

- ↑ Official report on the accident (in PDF format)

- ↑ Logbook entry of first neutrinos seen at Super-K generated at KEK

- ↑ S. Fukuda; et al. (1 April 2003), "The Super-Kamiokande detector", Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A, 51: 418–462, Bibcode:2003NIMPA.501..418F, doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00425-X

- ↑ Fukuda, Y.; et al. (1998). "Evidence for oscillation of atmospheric neutrinos". Physical Review Letters. 81 (8): 1562–1567. Bibcode:1998PhRvL..81.1562F. arXiv:hep-ex/9807003

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.81.1562.

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.81.1562. - ↑ Accident grounds neutrino lab

- ↑ Kearns; Kajita; Totsuka (August 1999), "Detecting Massive Neutrinos", Scientific American

- ↑ "Search for proton decay via p → νKþ using 260 kiloton · year data of Super-Kamiokande". Physical Review D. 90 (7): 072005. 14 Oct 2014. Bibcode:2014arXiv1408.1195T. arXiv:1408.1195

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.90.072005.

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.90.072005. - ↑ http://whitehotmagazine.com/articles/andreas-gursky-matthew-marks-gallery/493