Sulfur tetrafluoride

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Sulfur(IV) fluoride | |||

| Other names

Sulfur tetrafluoride | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.103 | ||

| PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number | WT4800000 | ||

| UN number | 2418 | ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| SF4 | |||

| Molar mass | 108.07 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | colorless gas | ||

| Density | 1.95 g/cm3, −78 °C | ||

| Melting point | −121.0 °C | ||

| Boiling point | −38 °C | ||

| reacts | |||

| Vapor pressure | 10.5 atm (22°C)[1] | ||

| Structure | |||

| Seesaw (C2v) | |||

| 0.632 D[2] | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Main hazards | highly toxic corrosive | ||

| Safety data sheet | ICSC 1456 | ||

| NFPA 704 | |||

| US health exposure limits (NIOSH): | |||

| PEL (Permissible) |

none[1] | ||

| REL (Recommended) |

C 0.1 ppm (0.4 mg/m3)[1] | ||

| IDLH (Immediate danger) |

N.D.[1] | ||

| Related compounds | |||

| Other anions |

Sulfur dichloride Disulfur dibromide Sulfur trifluoride | ||

| Other cations |

Oxygen difluoride Selenium tetrafluoride Tellurium tetrafluoride Polonium tetrafluoride | ||

| Related sulfur fluorides |

Disulfur difluoride Sulfur difluoride Disulfur decafluoride Sulfur hexafluoride | ||

| Related compounds |

Thionyl fluoride | ||

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Sulfur tetrafluoride is the chemical compound with the formula SF4. This species exists as a gas at standard conditions. It is a corrosive species that releases dangerous HF upon exposure to water or moisture. Despite these unwelcome characteristics, this compound is a useful reagent for the preparation of organofluorine compounds,[3] some of which are important in the pharmaceutical and specialty chemical industries.

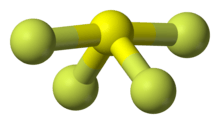

Structure

Sulfur in SF4 is in the formal +4 oxidation state. Of sulfur's total of six valence electrons, two form a lone pair. The structure of SF4 can therefore be anticipated using the principles of VSEPR theory: it is a see-saw shape, with S at the center. One of the three equatorial positions is occupied by a nonbonding lone pair of electrons. Consequently, the molecule has two distinct types of F ligands, two axial and two equatorial. The relevant bond distances are S–Fax = 164.3 pm and S–Feq = 154.2 pm. It is typical for the axial ligands in hypervalent molecules to be bonded less strongly. In contrast to SF4, the related molecule SF6 has sulfur in the 6+ state, no valence electrons remain nonbonding on sulfur, hence the molecule adopts a highly symmetrical octahedral structure. Further contrasting with SF4, SF6 is extraordinarily inert chemically.

The 19F NMR spectrum of SF4 reveals only one signal, which indicates that the axial and equatorial F atom positions rapidly interconvert via pseudorotation.[4]

Synthesis and manufacture

SF4 is produced by the reaction of SCl2, Cl2, and NaF:

- SCl2 + Cl2 + 4 NaF → SF4 + 4 NaCl

Treatment of SCl2 with NaF also affords SF4, not SF2. SF2 is unstable, it condenses with itself to form SF4 and SSF2.[5]

Use of SF4 for the synthesis of fluorocarbons

In organic synthesis, SF4 is used to convert COH and C=O groups into CF and CF2 groups, respectively.[6] Certain alcohols readily give the corresponding fluorocarbon. Ketones and aldehydes give geminal difluorides. The presence of protons alpha to the carbonyl leads to side reactions and diminished (30–40%) yield. Also diols can give cyclic sulfite esters, (RO)2SO. Carboxylic acids convert to trifluoromethyl derivatives. For example treatment of heptanoic acid with SF4 at 100-130 °C produces 1,1,1-trifluoroheptane. Hexafluoro-2-butyne can be similarly produced from acetylenedicarboxylic acid. The coproducts from these fluorinations, including unreacted SF4 together with SOF2 and SO2, are toxic but can be neutralized by their treatment with aqueous KOH.

The use of SF4 is being superseded in recent years by the more conveniently handled diethylaminosulfur trifluoride, Et2NSF3, "DAST", where Et = CH3CH2.[7] This reagent is prepared from SF4:[8]

- SF4 + Me3SiNEt2 → Et2NSF3 + Me3SiF

Other reactions

Sulfur chloride pentafluoride (SF

5Cl), a useful source of the SF5 group, is prepared from SF4.[9]

Hydrolysis of SF4 gives sulfur dioxide:[10]

SF4 + 2 H2O → SO2 + 4 HF

This reaction proceeds via the intermediacy of thionyl fluoride, which usually does not interfere with the use of SF4 as a reagent.[5]

Toxicity

SF

4 reacts inside the lungs with moisture:[11]

- SF4 + 2 H2O → SO2 + 4 HF

References

- 1 2 3 4 "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards #0580". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ↑ Tolles, W. M.; W. M. Gwinn, W. D. (1962). "Structure and Dipole Moment for SF4". J. Chem. Phys. 36 (5): 1119–1121. doi:10.1063/1.1732702.

- ↑ C.-L. J. Wang, "Sulfur Tetrafluoride" in Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis (Ed: L. Paquette) 2004, J. Wiley & Sons, New York. doi:10.1002/047084289.

- ↑ Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E. "Inorganic Chemistry" Academic Press: San Diego, 2001. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- 1 2 F. S. Fawcett, C. W. Tullock, "Sulfur (IV) Fluoride: (Sulfur Tetrafluoride)" Inorganic Syntheses, 1963, vol. 7, pp 119–124. doi:10.1002/9780470132388.ch33

- ↑ Hasek, W. R. "1,1,1-Trifluoroheptane". Org. Synth.; Coll. Vol., 5, p. 1082

- ↑ A. H. Fauq, "N,N-Diethylaminosulfur Trifluoride" in Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis (Ed: L. Paquette) 2004, J. Wiley & Sons, New York. doi:10.1002/047084289.

- ↑ W. J. Middleton, E. M. Bingham. "Diethylaminosulfur Trifluoride". Org. Synth.; Coll. Vol., 6, p. 440

- ↑ Nyman, F., Roberts, H. L., Seaton, T. Inorganic Syntheses, 1966, Volume 8, p. 160 McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1966, doi:10.1002/9780470132395.ch42

- ↑ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-08-037941-9.

- ↑ Johnston, H. (2003). A Bridge not Attacked: Chemical Warfare Civilian Research During World War II. World Scientific. pp. 33–36. ISBN 981-238-153-8.