Sudden arrhythmic death syndrome

| SUNDS | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | sudden unexpected nocturnal death syndrome (SUNDS), sudden adult death syndrome (SADS), bed death |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | R96.0 |

Sudden arrhythmic death syndrome (SADS), also known as sudden adult death syndrome, sudden unexpected/unexplained death syndrome (SUDS) or sudden unexpected/unexplained nocturnal death syndrome (SUNDS), is a sudden unexpected death of adolescents and adults, mainly during sleep.[1][2] Sudden unexpected death syndrome is rare in most areas around the world. This syndrome occurs in populations that are culturally and genetically distinct and people who leave the population carry with them the vulnerability to sudden death during sleep. Sudden unexplained death syndrome was first noted in 1977 among southeast Asian Hmong refugees in the US.[3][4] The disease was again noted in Singapore, when a retrospective survey of records showed that 230 otherwise healthy Thai men died suddenly of unexplained causes between 1982 and 1990:[5] In the Philippines, where it is referred to in the vernacular as bangungot, which means "to rise and to moan in sleep" and in Japan it is known as Pokkuri which means "sudden and unexpectedly ceased phenomena".

A Tokyo Medical Examiner reported that every year several hundred evidently healthy men are found dead in their beds in the Tokyo District alone. These observations indicate that the recent sudden deaths of Southeast Asian refugees are not a new occurrence, but rather an ongoing pattern of sudden deaths that appears in mainland Southeast Asia. Sudden unexpected death syndrome once caused more deaths among males than car accidents in Southeast Asia.[6] Most of those affected are young males.[7] Although there has been a significant amount of research on this topic, scientists have not been able to determine the exact cause; it is thought to be the body’s failure to accurately coordinate electrical signals that cause the heart to beat and the blood to keep flowing. This syndrome is also very difficult to detect even with extensive tests and an electrocardiograph reading.

Signs and symptoms

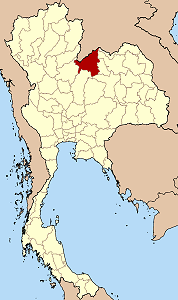

Southeast Asian immigrants, who were mostly fleeing the Vietnam War, most often had this syndrome, marking Southeast Asia as the area containing the most people with this fatal syndrome. However, there are other Asian populations that were affected, such as Filipinos and Chinese immigrants in the Philippines, Japanese in Japan, and natives of Guam in the United States and Guam.[8] Nonetheless, these particular immigrants who had this syndrome were about 33 years old and seemingly healthy and all but one of the Laotian Hmong refugees were men.[9] The condition appears to affect primarily young Hmong men from Laos (median age 33)[10] and northeastern Thailand (where the population are mainly of Laotian descent).[11][12]

Study background

Laotian Hmongs were chosen for the study because they had one of the highest sudden death rates while sleeping in the United States. They were originally from Southern China and the highlands of North Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand. The location that was picked for this study was in Ban Vinai in the Loei Province, which is approximately 15 kilometers from the Lao border. This study took place between October 1982 and June 1983 as this syndrome became more of a relevant pressing issue. Ban Vinai was the location chosen because it had 33,000 refugees in 1982, which was the largest population of victims.[8] Because this syndrome was occurring most commonly in those particular men, researchers found it most beneficial and effective to study the population in which they migrated from instead of studying victims and populations in the U.S. Because of religious limitations the Hmong men in Ban Vinai were not allowed to receive autopsies. Therefore, the only results and research obtained were victims outside of their religion or geographical area. An interview was arranged with the next of kin who lived with the victim, witnessed the death, or found the body. The interviews were open ended and allowed the person who was next of kin to describe what they witnessed and what preceding events they thought were relevant to the victim's death. The interviewers also collected information such as illness history, the circumstances of the death, demographic background, and history of any sleep disturbances. A genealogy was then created which included all the relatives and their vital status and circumstances of death.[8]

Causes

No cause of death is found, even after extensive examination in 5% of cases.[13]

A sudden death in a young person can be caused by heart disease (including cardiomyopathy, congenital heart disease, myocarditis, genetic connective tissue disorders, mitral valve prolapse or conduction disease), medication-related causes or other causes.[13]

Rare diseases called channelopathies may play a role such as long QT syndrome (LQTS), Brugada syndrome CPVT (catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia), PCCD (progressive cardiac conduction defect), early repolarisation syndrome, mixed sodium channel disease, and short QT syndrome.[13]

Medical examiners have taken into account various factors, such as nutrition, toxicology, heart disease, metabolism, and genetics. Although there is no real known definite cause, extensive research showed people 18 years or older were found to have suffered from a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a condition in which the heart muscle becomes oddly thickened without any obvious cause.[14] This was the most commonly identified abnormality in sudden death of young adults. In the instances where people experience sudden death, it is most commonly found that they were suffering from CAD (coronary artery disease) or ASCAD (atherosclerotic coronary artery disease), or any level of stress.[14] However, studies reveal that people experienced early symptoms within the week before the terminal event such as chest pain at ~52% of victims, dyspnea at ~22%, syncope at ~7% and ~19% who experienced no symptoms.[14] Scientists have also associated this syndrome with the gene SCN5A that is mutated and affects the function of the heart. However, all autopsies done on victims who suffered from this syndrome came back negative.[14]

In some cultures, SUNDS has been cloaked in superstition. Many Filipinos believe ingesting high levels of carbohydrates just before sleeping causes bangungot. It has only been recently that the scientific world has begun to understand this syndrome. Victims of bangungot have not been found to have any organic heart diseases or structural heart problems. However, cardiac activity during SUNDS episodes indicates irregular heart rhythms and ventricular fibrillation. The victim survives this episode if the heart's rhythm goes back to normal. Older Filipinos recommend wiggling the big toe of people experiencing this to encourage their heart to snap back to normal.[15]

In the Philippines, most cases of "bangungot" have been linked with acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis by Filipino medical personnel although the effect might have been due to changes in the pancreas during post-mortem autolysis.[16] In Thailand and Laos, bangungot (or in their term, sudden adult death syndrome) is caused by the Brugada syndrome.[17]

Treatment

The only proven way to prevent SADS is by implantation of a implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Oral antiarrhythmics such as propranolol are ineffective.[18]

Epidemiology

In 1980 a reported pattern of sudden deaths brought attention to the Centers for Disease Control. The first reported sudden death occurred in 1948 when there were 81 series of similar deaths of Filipino men in Oahu County, Hawaii. However, it did not become relevant because there was no pattern associated. This syndrome continued to become more significant as years went on. By the year of 1981-1982, the annual rate in the United States was high with 92/100,000 among Laotians-Hmong, 82/100,000 among other Laotian ethnic groups, and 59/100,000 among Cambodians.[8] This elevated rate is why the pattern of Asian sudden unexpected deaths was brought to attention in the United States.

Society and culture

Some say that the Hmong who died were killed by their own beliefs in the spiritual world, otherwise known as, "Nocturnal Pressing Spirit Attacks". In Indonesia it is called digeuton, which translates to "pressed on" in English.[9] In China it is called bèi guǐ yā (traditional Chinese: 被鬼壓; simplified Chinese: 被鬼压) which translates to "crushed by a ghost" in English.[9] The Dutch call the presence a nachtmerrie, the night-mare.[9] The "merrie" comes from the Middle Dutch mare, an incubus who "lies on people's chests, suffocating them". This phenomenon is well known among the Hmong people of Laos,[19] who ascribe these deaths to a malign spirit, dab tsuam (pronounced "da cho"), said to take the form of a jealous woman. Hmong men may even go to sleep dressed as women so as to avoid the attentions of this spirit.

During the 1970s and 1980s, when an outbreak of this syndrome began, many of the Southeast Asians were not able to worship properly due to the guerrilla war against the government of Laos with the United States. Hmong people believe that when they do not worship properly, do not perform religious ritual properly or forget to sacrifice, the ancestor spirits or the village spirits do not protect them, thus allowing the evil spirit to reach them. These attacks induce a nightmare that leads to sleep paralysis when the victim is conscious and experiencing pressure on the chest.[9] It is also common to have a REM state that is out of sequence where there is a mix of brain states that are normally held separate.[9] After the war, the United States government scattered the Hmong across the country to 53 different cities.[9] Once these nightmare visitations began, a shaman was recommended for psychic protection from the spirits of their sleep.[9] However, scattered across 53 different cities, these victims had no access to any or the right shaman to protect them from this syndrome.

Hmong people believed that rejecting the role of becoming a shaman, they are taken into the spirit world.

Bangungot is depicted in the Philippines as a mythological creature called batibat or bangungot. This hag-like creature sits on the victim's face or chest so as to immobilize and suffocate him. When this occurs, the victim usually experiences paralysis. It's said that one should bite their tongue and wiggle their toes to try to get out of this paralysis or they may die from suffocation.

Name variations in English

| Name | Acronym | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| sudden unexpected death syndrome | SUDS | |

| sudden unexplained death syndrome | SUDS | |

| sudden unexpected nocturnal death syndrome | SUNDS | |

| sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome | SUNDS | |

| sudden adult death syndrome | SADS | (parallel in form with SIDS) |

| sudden arrhythmia death syndrome | SADS | |

| sudden arrhythmic death syndrome | SADS | |

| sudden arrhythmic cardiac death syndrome | — | |

| bed death | — | |

Names in different languages

| Term | Language | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| bangungot or urom | Filipino[20] | The term originated from the Tagalog word meaning "to rise and moan in sleep".[16] It is also the Tagalog word for nightmare. |

| dab tsog | Hmong[19] | |

| lai tai | Thai | (Thai: ใหลตาย; meaning "sleep and die")[11][21] |

| dolyeonsa | Korean | |

| pokkuri disease | Japanese[22] | |

| ya thoom | Arabic | |

| albarsty (Kyrgyz: албарсты) | Kyrgyz | |

See also

- Brugada syndrome

- Night hag

- Sleep paralysis

- Sudden infant death syndrome

- Sudden unexplained death in childhood

- Yunnan sudden death syndrome

References

- ↑ "Documentary maker died of sudden adult death syndrome, coroner rules" by Caroline Davies, The Guardian, December 12, 2013, Retrieved 2013-12-31

- ↑ Also known as SUDS. See: Reddy PR, Reinier K, Singh T, Mariani R, Gunson K, Jui J, Chugh SS. Physical activity as a trigger of sudden cardiac arrest: The Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study. Int J Cardiol. 2008

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (1981). "Sudden, unexpected, nocturnal deaths among Southeast Asian refugees". MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 30 (47): 581–589. PMID 6796814.

- ↑ Parrish RG, Tucker M, Ing R, Encarnacion C, Eberhardt M (1987). "Sudden unexplained death syndrome in Southeast Asian refugees: a review of CDC surveillance". MMWR CDC Surveil Summ. 36 (1): 43SS–53SS. PMID 3110586.

- ↑ Goh KT, Chao TC, Chew CH (1990). "Sudden nocturnal deaths among Thai construction workers in Singapore". Lancet. 335 (8698): 1154. PMID 1971883. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(90)91153-2.

- ↑ "Can You Really Die in Your Nightmares?". LiveScience.com. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

- ↑ Gervacio-Domingo, G.; F . Punzalan; M . Amarillo; A . Dans. "Sudden unexplained death during sleep occurred commonly in the general population in the Philippines: a sub study of the National Nutrition and Health Survey .". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 60 (6): 561–571. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.10.003. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- 1 2 3 4 Munger, Ronald (September 1987). "Sudden Death in Sleep of Loatian-Hmong Refugees in Thailand: A Case-Control Study" (PDF). AJPH. 77: 1187–90. PMC 1647019

. PMID 3618851. doi:10.2105/ajph.77.9.1187. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

. PMID 3618851. doi:10.2105/ajph.77.9.1187. Retrieved February 22, 2016. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Madrigal, Alexis C. "The Dark Side of the Placebo Effect: When Intense Belief Kills". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

- ↑ Munger RG (1987). "Sudden death in sleep of Laotian-Hmong refugees in Thailand: a case-control study". Am J Public Health. 77 (9): 1187–90. PMC 1647019

. PMID 3618851. doi:10.2105/AJPH.77.9.1187.

. PMID 3618851. doi:10.2105/AJPH.77.9.1187. - ↑ Tungsanga K, Sriboonlue P (1993). "Sudden unexplained death syndrome in north-east Thailand". Int J Epidemiol. 22 (1): 81–7. PMID 8449651. doi:10.1093/ije/22.1.81.

- 1 2 3 Elijah R Behr. "When a young person dies suddenly" (PDF). Cardiac Risk in the Young - CRY. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-20.

- 1 2 3 4 Eckart, Robert E.; Shry, Eric A.; Burke, Allen P.; McNear, Jennifer A.; Appel, David A.; Castillo-Rojas, Laudino M.; Avedissian, Lena; Pearse, Lisa A.; Potter, Robert N. "Sudden Death in Young Adults". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 58 (12): 1254–1261. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.049.

- ↑ Ramos, Maximo D. (1971). Creatures of Philippine Lower Mythology. Philippines: University of the Philippines Press.

- 1 2 Munger, Ronald G.; Booton, Elizabeth A. (1998). "Bangungut in Manila: sudden and unexplained death in sleep of adult Filipinos" (PDF). International Journal of Epidemiology. 27 (4): 677–684. PMID 9758125. doi:10.1093/ije/27.4.677. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 2011-07-29.

- ↑ Tessa R. Salazar (June 19, 2004). "Bangungot' in family? See a heart specialist". Inquirer News Service. Archived from the original on 2004-06-30.

- ↑ Nademanee K, Veerakul G, Mower M, et al. (2003). "Defibrillator Versus beta-Blockers for Unexplained Death in Thailand (DEBUT): a randomized clinical trial". Circulation. 107 (17): 2221–6. PMID 12695290. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000066319.56234.C8.

- 1 2 Adler SR (1995). "Refugee stress and folk belief: Hmong sudden deaths". Soc Sci Med. 40 (12): 1623–9. PMID 7660175. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(94)00347-V.

- ↑ Munger RG, Booton EA (1998). "Bangungut in Manila: sudden and unexplained death in sleep of adult Filipinos". Int J Epidemiol. 27 (4): 677–84. PMID 9758125. doi:10.1093/ije/27.4.677.

- ↑ Himmunngan P, Sangwatanaroj S, Petmitr S, Viroonudomphol D, Siriyong P, Patmasiriwat P (March 2006). "HLa-class II (DRB & DQB1) in Thai sudden unexplained death syndrome (Thai SUDS) families (Lai-Tai families)". Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health. 37 (2): 357–65. PMID 17124999.

- ↑ Gotoh K (1976). "A histopathological study on the conduction system of the so-called "Pokkuri disease" (sudden unexpected cardiac death of unknown origin in Japan". Jpn Circ J. 40 (7): 753–68. PMID 966364. doi:10.1253/jcj.40.753.

Further reading

- Agence France Presse (8 April 2002). "Sleeping death syndrome terrorises young men". The Borneo Post.

- Center for Disease Control (23 September 1988). "Sudden Unexplained Death Syndrome Among Southeast Asian Refugees". MMWR.