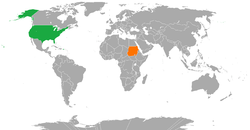

Sudan–United States relations

| |

United States |

Sudan |

|---|---|

Sudan – United States relations refer to bilateral relations between Sudan and United States. The United States is critical of Sudan's human rights record and has sent a strong UN Peacekeeping force to Darfur.

A review of relations

Sudan broke diplomatic relations with the U.S. in June 1967, following the outbreak of the Arab-Israeli War. Relations improved after July 1971, when the Sudanese Communist Party attempted to overthrow President Nimeiry, and Nimeiry suspected Soviet involvement. U.S. assistance for resettlement of refugees following the 1972 peace settlement with the south added further improved relations.

On March 1, 1973, Palestinian terrorists of the "Black September" organization murdered U.S. Ambassador Cleo A. Noel and Deputy Chief of Mission Curtis G. Moore in Khartoum. Sudanese officials arrested the terrorists and tried them on murder charges. In June 1974, however, they were released to the custody of the Egyptian Government. The U.S. Ambassador to the Sudan was withdrawn in protest. Although the U.S. Ambassador returned to Khartoum in November, relations with the Sudan remained static until early 1976, when President Nimeiri mediated the release of 10 American hostages being held by Eritrean insurgents in rebel strongholds in northern Ethiopia. In 1976, the U.S. decided to resume economic assistance to Sudan.

In late 1985, there was a reduction in staff at the U.S. Embassy in Khartoum because of the presence of a large contingent of Libyan terrorists. In April 1986, relations with Sudan deteriorated when the U.S. bombed Tripoli, Libya. A U.S. Embassy employee was shot on April 16, 1986. Immediately following this incident, all non-essential personnel and all dependents left for six months. At this time, Sudan was the single largest recipient of U.S. development and military assistance in sub-Saharan Africa. However, official U.S. development assistance was suspended in 1989 in the wake of the military coup against the elected government, which brought to power the National Islamic Front led by General Bashir.

U.S. relations with Sudan were further strained in the 1990s. Sudan backed Iraq in its invasion of Kuwait and provided sanctuary and assistance to Islamic terrorist groups. In the early and mid-1990s, Carlos the Jackal, Osama bin Laden, Abu Nidal, and other terrorist leaders resided in Khartoum. Sudan's role in the radical Pan-Arab Islamic Conference represented a matter of great concern to the security of American officials and dependents in Khartoum, resulting in several drawdowns and/or evacuations of U.S. personnel from Khartoum in the early-mid 1990s. Sudan's Islamist links with international terrorist organizations represented a special matter of concern for the U.S. Government, leading to Sudan's 1993 designation as a state sponsor of terrorism and a suspension of U.S. Embassy operations in Khartoum in 1996. In October 1997, the U.S. imposed comprehensive economic, trade, and financial sanctions against the Sudan. In August 1998, in the wake of the East Africa embassy bombings, the U.S. launched cruise missile strikes against Sudan's Al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory. The last U.S. Ambassador to the Sudan, Ambassador Tim Carney, departed post prior to this event and no new ambassador has been designated since. The U.S. Embassy is headed by a charge d'affaires.

The U.S. and Sudan entered into a bilateral dialogue on counterterrorism in May 2000. Sudan has provided concrete cooperation against international terrorism since the September 11 attacks in 2001 on New York and Washington. However, although Sudan publicly supported the international coalition actions against the al Qaida network and the Taliban in Afghanistan, the government criticized the U.S. strikes in that country and opposed a widening of the effort against international terrorism to other countries. Sudan remains on the state sponsors of terrorism list.

In response to the Government of Sudan's continued complicity in unabated violence occurring in Darfur, President George W. Bush imposed new economic sanctions on Sudan in May 2007. The sanctions blocked assets of Sudanese citizens implicated in Darfur violence, and also sanctioned additional companies owned or controlled by the Government of Sudan. Sanctions continue to underscore U.S. efforts to end the suffering of the millions of Sudanese affected by the crisis in Darfur. Sudan has often accused the United States of threatening its territorial integrity by supporting referendums in the South and in Darfur.

Despite policy differences the U.S. has been a major donor of humanitarian aid to the Sudan throughout the last quarter century. The U.S. was a major donor in the March 1989 "Operation Lifeline Sudan," which delivered 100,000 metric tons of food into both government and SPLA-held areas of the Sudan, thus averting widespread starvation. In 1991, the U.S. made major donations to alleviate food shortages caused by a two-year drought. In a similar drought in 2000-01, the U.S. and the international community responded to avert mass starvation in the Sudan. In 2001 the Bush Administration named a Presidential Envoy for Peace in the Sudan to explore what role the U.S. could play in ending Sudan's civil war and enhancing the delivery of humanitarian aid. For fiscal years 2005-2006, the U.S. Government committed almost $2.6 billion to Sudan for humanitarian assistance and peacekeeping in Darfur as well as support for implementation of the peace accord and reconstruction and development in southern Sudan.

However, relations between both countries have, at least, the hope of improving due to President Obama's sending of Special Envoy Scott Gration to Sudan to improve diplomatic conditions, and discuss ways to avert the current Darfur conflict. On September 9, 2009, the United States has published a new law to ease the sanctions on parts of Sudan. Obama named Donald E. Booth as his special envoy for Sudan and South Sudan on 28 August 2013.[1][2] On January 13, 2017, the United States lifted economic and trade sanctions on Sudan due to cooperation with the Sudanese government in fighting terrorism, reducing conflict, and denying safe haven to South Sudanese rebels and improving humanitarian access to people in need. The White House announced the easing of sanctions as part of a five-track engagement process.[3] On March 16, 2017, the US and Sudan announced the resumption of military relations after exchanging military attachés.[4] In April 2017, it was announced that the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had decided to open an office in Khartoum.[5]

Principal U.S. officials

- Ambassador—vacant

See also

- Embassy of Sudan in Washington, D.C.

- Foreign relations of Sudan

- Foreign relations of the United States

- United States aid to Sudan

- United States policy on conflict mitigation and reconciliation in Sudan

References

- ↑ "Statement by the President Announcing the Appointment of Ambassador Donald Booth as U.S. Special Envoy for Sudan and South Sudan". White House Office of the Press Secretary. 28 August 2013. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ↑ Madhani, Aamer (28 August 2013). "Obama names special envoy for South Sudan and Sudan". USA Today. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ↑ "Obama to ease Sudan sanctions on way out". Associated Press. November 10, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ↑ "US, Sudan resume military ties after 24-year hiatus". Anadolu Agency. March 16, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Sudanese official defends decision to have CIA office in Khartoum". Middle East Monitor. April 11, 2017. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of State website http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/index.htm (Background Notes).

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of State website http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/index.htm (Background Notes).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sudan – United States relations. |

- Embassy of Sudan - Washington, DC

- Embassy of U.S.A. - Khartoum

- Consultae General of U.S.A. - Juba

- U.S. Special Envoy to Sudan

- Sudanese-U.S. Foreign Relations from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

.svg.png)