Aid

In international relations, aid (also known as international aid, overseas aid, foreign aid or foreign assistance) is – from the perspective of governments – a voluntary transfer of resources from one country to another.

Aid may serve one or more functions: it may be given as a signal of diplomatic approval, or to strengthen a military ally, to reward a government for behaviour desired by the donor, to extend the donor's cultural influence, to provide infrastructure needed by the donor for resource extraction from the recipient country, or to gain other kinds of commercial access. Humanitarian and altruistic purposes are at least partly responsible for the giving of aid.[1]

Aid may be given by individuals, private organizations, or governments. Standards delimiting exactly the types of transfers considered "aid" vary from country to country. For example, the United States government discontinued the reporting of military aid as part of its foreign aid figures in 1958.[2] The most widely used measure of aid is "Official Development Assistance" (ODA).

Definitions and purpose

The Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development defines its aid measure, Official Development Assistance (ODA), as follows: "ODA consists of flows to developing countries and multilateral institutions provided by official agencies, including state and local governments, or by their executive agencies, each transaction of which meets the following test: a) it is administered with the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective, and b) it is concessional in character and contains a grant element of at least 25% (calculated at a rate of discount of 10%)." (OECD, The DAC in Dates, 2006. Section, "1972".) Foreign aid has increased since 1950's and 1960's (Isse 129). The notion that foreign aid increases economic performance and generates economic growth is based on Chenery and Strout's Dual Gap Model(Isse 129). Chenerya and Strout (1966) claimed that foreign aid promotes development by adding to domestic savings as well as to foreign exchange availability, this helping to close either the savings-investment gap or the export-import gap. (Isse 129).

Carol Lancaster defines foreign aid as "a voluntary transfer of public resources, from a government to another independent government, to an NGO, or to an international organization (such as the World Bank or the UN Development Program) with at least a 25 percent grant element, one goal of which is to better the human condition in the country receiving the aid."[3]

Lancaster also states that for much of the period of her study (World War Two to the present) "foreign aid was used for four main purposes: diplomatic [including military/security and political interests abroad], developmental, humanitarian relief and commercial."[4]

Extent of aid

Most official development assistance (ODA) comes from the 28 members of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC), or about $135 billion in 2013. A further $15.9 billion came from the European Commission and non-DAC countries gave an additional $9.4 billion. Although development aid rose in 2013 to the highest level ever recorded, a trend of a falling share of aid going to the neediest sub-Saharan African countries continued.[5]

Top recipient countries

| Country | US$, billions |

|---|---|

| | 4.82 |

| | 4.22 |

| | 4.2 |

| | 3.61 |

| | 3.59 |

| | 3.53 |

| | 3.44 |

| | 2.98 |

| | 2.7 |

| | 2.67 |

Top donor countries

As of 2013, Official development assistance (in absolute terms) contributed by the top 10 DAC countries is as follows. European Union countries together gave $70.73 billion and EU Institutions gave a further $15.93 billion.[5][7]

-

European Union – $86.66 billion

European Union – $86.66 billion

-

-

United States – $31.55 billion

United States – $31.55 billion -

United Kingdom – $17.88 billion

United Kingdom – $17.88 billion -

Germany – $14.06 billion

Germany – $14.06 billion -

Japan – $11.79 billion

Japan – $11.79 billion -

France – $11.38 billion

France – $11.38 billion -

Sweden – $5.83 billion

Sweden – $5.83 billion -

Norway – $5.58 billion

Norway – $5.58 billion -

Netherlands – $5.44 billion

Netherlands – $5.44 billion -

Canada – $4.91 billion

Canada – $4.91 billion -

Australia – $4.85 billion

Australia – $4.85 billion

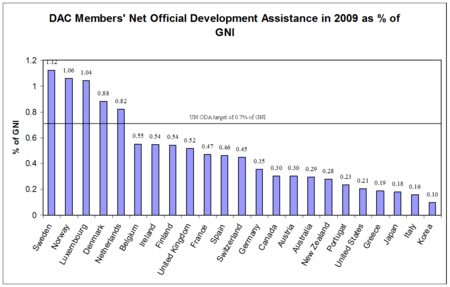

Official development assistance as a percentage of gross national income contributed by the top 10 DAC countries is as follows. Five countries met the longstanding UN target for an ODA/GNI ratio of 0.7% in 2013:[5]

-

Norway – 1.07%

Norway – 1.07% -

Sweden – 1.02%

Sweden – 1.02% -

Luxembourg – 1.00%

Luxembourg – 1.00% -

Denmark – 0.85%

Denmark – 0.85% -

United Kingdom – 0.72%

United Kingdom – 0.72% -

Netherlands – 0.67%

Netherlands – 0.67% -

Finland – 0.55%

Finland – 0.55% -

Switzerland – 0.47%

Switzerland – 0.47% -

.svg.png) Belgium – 0.45%

Belgium – 0.45% -

Ireland – 0.45%

Ireland – 0.45%

European Union countries that are members of the Development Assistance Committee gave 0.42% of GNI (excluding the $15.93 billion given by EU Institutions).[5]

Types

The type of aid given may be classified according to various factors, including its intended purpose, the terms or conditions (if any) under which it is given, its source, and its level of urgency.

Intended purpose

Official aid may be classified by types according to its intended purpose. Military aid is material or logistical assistance given to strengthen the military capabilities of an ally country.[8] Humanitarian aid is material or logistical assistance provided for humanitarian purposes, typically in response to humanitarian crises such as a natural disaster or a man-made disaster.[9]

Terms or conditions of receipt

Aid can also be classified according to the terms agreed upon by the donor and receiving countries. In this classification, aid can be a gift, a grant, a low or no interest loan, or a combination of these. The terms of foreign aid are oftentimes influenced by the motives of the giver: a sign of diplomatic approval, to reward a government for behaviour desired by the donor, to extend the donor's cultural influence, to enhance infrastructure needed by the donor for the extraction of resources from the recipient country, or to gain other kinds of commercial access.[1]

Sources

Aid can also be classified according to its source. While government aid is generally called foreign aid, aid that originates in institutions of a religious nature is often termed faith-based foreign aid.[10] Aid from various sources can reach recipients through bilateral or multilateral delivery systems. "Bilateral" refers to government to government transfers. "Multilateral" institutions, such as the World Bank or UNICEF, pool aid from one or more sources and disperse it among many recipients.

International aid in the form of gifts by individuals or businesses (aka, "private giving") are generally administered by charities or philanthropic organizations who batch them and then channel these to the recipient country.

Urgency

Aid may be also classified based on urgency into emergency aid and development aid. Emergency aid is rapid assistance given to a people in immediate distress by individuals, organizations, or governments to relieve suffering, during and after man-made emergencies (like wars) and natural disasters. The term often carries an international connotation, but this is not always the case. It is often distinguished from development aid by being focused on relieving suffering caused by natural disaster or conflict, rather than removing the root causes of poverty or vulnerability. Development aid is aid given to support development in general which can be economic development or social development in developing countries. It is distinguished from humanitarian aid as being aimed at alleviating poverty in the long term, rather than alleviating suffering in the short term.

Emergency aid

The provision of emergency humanitarian aid consists of the provision of vital services (such as food aid to prevent starvation) by aid agencies, and the provision of funding or in-kind services (like logistics or transport), usually through aid agencies or the government of the affected country. Humanitarian aid is distinguished from humanitarian intervention, which involves armed forces protecting civilians from violent oppression or genocide by state-supported actors.

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is mandated to coordinate the international humanitarian response to a natural disaster or complex emergency acting on the basis of the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 46/182. The Geneva Conventions give a mandate to the International Committee of the Red Cross and other impartial humanitarian organizations to provide assistance and protection of civilians during times of war. The ICRC, has been given a special role by the Geneva Conventions with respect to the visiting and monitoring of prisoners of war.

Development aid

Development aid is given by governments through individual countries' international aid agencies and through multilateral institutions such as the World Bank, and by individuals through development charities. For donor nations, development aid also has strategic value; improved living conditions can positively affect global security and economic growth. Official Development Assistance (ODA) is a commonly used measure of developmental aid.

Intended use

Aid given is generally intended for use by a specific end. From this perspective it may be called:

- Project aid: Aid given for a specific purpose; e.g. building materials for a new school.

- Programme aid: Aid given for a specific sector; e.g. funding of the education sector of a country.

- Budget support: A form of Programme Aid that is directly channelled into the financial system of the recipient country.

- Sector-wide Approaches (SWAPs): A combination of Project aid and Programme aid/Budget Support; e.g. support for the education sector in a country will include both funding of education projects (like school buildings) and provide funds to maintain them (like school books).

- Technical assistance: Aid involving highly educated or trained personnel, such as doctors, who are moved into a developing country to assist with a program of development. Can be both programme and project aid.

- Food aid: Food is given to countries in urgent need of food supplies, especially if they have just experienced a natural disaster. Food aid can be provided by importing food from the donor, buying food locally, or providing cash.

- International research, such as research that used for the green revolution or vaccines.

Official Development Assistance (ODA)

Official development assistance (ODA) is a term coined by the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to measure aid. ODA refers to aid from national governments for promoting economic development and welfare in low and middle income countries. ODA can be bilateral or multilateral. This aid is given as either grants, where no repayment is required, or as concessional loans, where interest rates are lower than market rates.[11]

Loan repayments to multilateral institutions are pooled and redistributed as new loans. Additionally, debt relief, partial or total cancellation of loan repayments, is often added to total aid numbers even though it is not an actual transfer of funds. It is compiled by the Development Assistance Committee. The United Nations, the World Bank, and many scholars use the DAC's ODA figure as their main aid figure because it is easily available and reasonably consistently calculated over time and between countries.[11] The DAC classifies aid in three categories:

- Official Development Assistance (ODA): Development aid provided to developing countries (on the "Part I" list) and international organizations with the clear aim of economic development.[12]

- Official Aid (OD): Development aid provided to developed countries (on the "Part II" list).

- Other Official Flows (OOF): Aid which does not fall into the other two categories, either because it is not aimed at development, or it consists of more than 75% loan (rather than grant).

Aid is often pledged at one point in time, but disbursements (financial transfers) might not arrive until later.

In 2009, South Korea became the first major recipient of ODA from the OECD to turn into a major donor. The country now provides over $1 billion in aid annually.[13]

Not included as international aid

Most monetary flows between nations are not counted as aid. These include market-based flows such as foreign direct investments and portfolio investments, remittances from migrant workers to their families in their home countries, and military aid. In 2009, aid in the form of remittances by migrant workers in the United States to their international families was twice as large as that country's humanitarian aid.[14] The World Bank reported that, worldwide, foreign workers sent $328 billion from richer to poorer countries in 2008, over twice as much as official aid flows from OECD members.[14] The United States does not count military aid in its foreign aid figures.

Improving aid effectiveness

The High Level Forum is a gathering of aid officials and representatives of donor and recipient countries. Its Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness outlines rules to improve the quality of aid.

Conditionalities

A major proportion of aid from donor nations is tied, mandating that a receiving nation spend on products and expertise originating only from the donor country. [15] Eritrea discovered that it would be cheaper to build its network of railways with local expertise and resources rather than to spend aid money on foreign consultants and engineers.[15] US law, backed by strong farm interests,[16] requires food aid be spent on buying food at home, instead of where the hungry live, and, as a result, half of what is spent is used on transport.[17] As a result, tying aid is estimated to increase the cost of aid by 15–30%.[18] Oxfam America and American Jewish World Service report that reforming US food aid programs could extend food aid to an additional 17.1 million people around the world.[19]

The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, as primary holders of developing countries' debt, attach structural adjustment conditionalities to loans which generally include the elimination of state subsidies and the privatization of state services. For example, the World Bank presses poor nations to eliminate subsidies for fertilizer even while many farmers cannot afford them at market prices.[20] In the case of Malawi, almost five million of its 13 million people used to need emergency food aid. However, after the government changed policy and subsidies for fertilizer and seed were introduced, farmers produced record-breaking corn harvests in 2006 and 2007 as production leaped to 3.4 million in 2007 from 1.2 million in 2005, making Malawi a major food exporter.[20] In the former Soviet states, the reconfiguration of public financing in their transition to a market economy called for reduced spending on health and education, sharply increasing poverty.[21][22][23]

The EU subsidizes its agricultural sectors in the expense of Latin America who must liberalize trade in order to qualify for aid. Latin America, a country with a comparative advantage on agriculture and a great reliance on its agricultural export sector, loses $4 billion annually due to EU farming subsidy policies. Carlos Santiso advocates a "radical approach in which donors cede control to the recipient country".[24]

Cash aid versus in-kind aid

A report by a High Level Panel on Humanitarian Cash Transfers found that only 6% of aid is delivered in the form of cash or vouchers.[25] But there is a growing realization among aid groups that, for locally available goods, giving cash or cash vouchers instead of imported goods is a cheaper, faster, and more efficient way to deliver aid.[26]

Evidence shows that cash can be more transparent, more accountable, more cost effective, help support local markets and economies, and increase financial inclusion and give people more dignity and choice.[25] Sending cash is cheaper as it does not have the same transaction costs as shipping goods. Sending cash is also faster than shipping the goods. In 2009 for sub-Saharan Africa, food bought locally by the WFP cost 34 percent less and arrived 100 days faster than food sent from the United States, where buying food from the United States is required by law.[27] Cash aid also helps local food producers, usually the poorest in their countries, while imported food may damage their livelihoods and risk continuing hunger in the future.[27]

The World Food Program (WFP), the biggest non-governmental distributor of food, announced that it will begin distributing cash and vouchers instead of food in some areas, which Josette Sheeran, the WFP's executive director, described as a "revolution" in food aid.[26][28]

Coordination

While the number of Non-governmental Organization have increased dramatically over the past few decades, fragmentation in aid policy is an issue.[18] Because of such fragmentation, health workers in several African countries, for example, say they are so busy meeting western delegates that they can only do their proper jobs in the evening.[18]

One of the Paris Declaration's priorities is to reduce systems of aid that are "parallel" to local systems.[18] For example, Oxfam reported that, in Mozambique, donors are spending $350 million a year on 3,500 technical consultants, which is enough to hire 400,000 local civil servants, weakening local capacity.[18] Between 2005 and 2007, the number of parallel systems did fall, by about 10% in 33 countries.[18] In order to improve coordination and reduce parallel systems, the Paris Declaration suggests that aid recipient countries lay down a set of national development priorities and that aid donors fit in with those plans.[18]

Aid priorities

Laurie Garret, author of the article "The Challenge of Global Health" points out that the current aid and resources are being targeted at very specific, high-profile diseases, rather than at general public health. Aid is "stovepiped" towards narrow, short-term goals relating to particular programs or diseases such as increasing the amount of people receiving anti-retroviral treatment, and increasing distribution of bed nets. These are band aid solutions to larger problems, as it takes healthcare systems and infrastructure to create significant change. Donors lack the understanding that effort should be focused on broader measures that affect general well being of the population, and substantial change will take generations to achieve. Aid often does not provide maximum benefit to the recipient, and reflects the interests of the donor.[29]

Furthermore, consider the breakdown, where aid goes and for what purposes. In 2002, total gross foreign aid to all developing countries was $76 billion. Dollars that do not contribute to a country’s ability to support basic needs interventions are subtracted. Subtract $6 billion for debt relief grants. Subtract $11 billion, which is the amount developing countries paid to developed nations in that year in the form of loan repayments. Next, subtract the aid given to middle income countries, $16 billion. The remainder, $43 billion, is the amount that developing countries received in 2002. But only $12 billion went to low-income countries in a form that could be deemed budget support for basic needs.[30] When aid is given to the Least Developed Countries who have good governments and strategic plans for the aid, it is thought that it is more effective.[30]

Logistics

Humanitarian aid is argued to often not reach those who are intended to receive it. For example, a report composed by the World Bank in 2006 stated that an estimated half of the funds donated towards health programs in sub-Saharan Africa did not reach the clinics and hospitals. Money is paid out to fake accounts, prices are increased for transport or warehousing, and drugs are sold to the black market. Another example is in Ghana, where approximately 80% of donations do not go towards their intended purposes. This type of corruption only adds to the criticism of aid, as it is not helping those who need it, and may be adding to the problem.[29] Only about one fifth of U.S. aid goes to countries classified by the OECD as ‘least developed.’[31] This “pro-rich” trend is not unique to the United States.[30][31] According to Collier, “the middle income countries get aid because they are of much more commercial and political interest than the tiny markets and powerlessness of the bottom billion.”[32] What this means is that, at the most basic level, aid is not targeting the most extreme poverty.[30][31]

The logistics in which the delivery of humanitarian occurs can be problematic. For example, an earthquake in 2003 in Bam, Iran left tens of thousands of people in need of disaster zone aid. Although aid was flown in rapidly, regional belief systems, cultural backgrounds and even language seemed to have been omitted as a source of concern. Items such as religiously prohibited pork, and non-generic forms of medicine that lacked multilingual instructions came flooding in as relief. An implementation of aid can easily be problematic, causing more problems than it solves.[33]

Considering transparency, the amount of aid that is recorded accurately has risen from 42% in 2005 to 48% in 2007.[18]

Improving the economic efficiency of aid

Currently, donor institutions make proposals for aid packages to recipient countries. The recipient countries then make a plan for how to use the aid based on how much money has been given to them. Alternatively, NGO's receive funding from private sources or the government and then implement plans to address their specific issues. According to Sachs, in the view of some scholars, this system is inherently ineffective.[30]

According to Sachs, we should redefine how we think of aid. The first step should be to learn what developing countries hope to accomplish and how much money they need to accomplish those goals. Goals should be made with the Millennium Development Goals in mind for these furnish real metrics for providing basic needs. The “actual transfer of funds must be based on rigorous, country-specific plans that are developed through open and consultative processes, backed by good governance in the recipient countries, as well as careful planning and evaluation.”[30] With the Millennium Development Goals deemed to have been accomplished, the current (2015) approach agreed by a more consultative process is through the Sustainable Development Goals, which acknowledge the need for international integrated development[34] applied for coordination, planning, implementation and evaluation as a means of increasing efficiency of delivery. The goals and approach embrace a wider ambit than traditional aid or development assistance and extend to the experiences of private sector and NGOs in both developed and developing nations that experience rapid economic growth.

Possibilities are also emerging as some developing countries are experiencing rapid economic growth, they are able to provide their own expertise gained from their recent transition. This knowledge transfer can be seen in donors, such as Brazil, whose $1 billion in aid outstrips that of many traditional donors.[35] Brazil provides most of its aid in the form of technical expertise and knowledge transfers.[35] This has been described by some observers as a 'global model in waiting'.[36]

Criticism

A very wide range of interpretations are in play ranging from the argument that foreign aid has been a primary driver of development, to a complete waste of money. A middle of the road viewpoint is that aid has shown modest favorable impacts in some areas especially regarding health indicators, agriculture, disaster relief, and post-conflict reconstruction.[37] Statistical studies have produced widely differing assessments of the correlation between aid and economic growth, and no firm consensus has emerged to suggest that foreign aid generally does boost growth. Some studies find a positive correlation,[38] while others find either no correlation or a negative correlation.[39] In the case of Africa, Asante (1985) gives the following assessment:

Summing up the experience of African countries both at the national and at the regional levels it is no exaggeration to suggest that, on balance, foreign assistance, especially foreign capitalism, has been somewhat deleterious to African development. It must be admitted, however, that the pattern of development is complex and the effect upon it of foreign assistance is still not clearly determined. But the limited evidence available suggests that the forms in which foreign resources have been extended to Africa over the past twenty-five years, insofar as they are concerned with economic development, are, to a great extent, counterproductive.[40]

There have been numerous reasons proffered to explain these counterproductive effects of aid. One view is that aid can hinder the development of effective public institutions in recipient countries through reducing the need for a government to collect revenue from its citizens, thereby also making it less accountable to them.[41] Aid can also prove detrimental to state development if it is captured by rebel groups, causing an increase in the incidence and length of intrastate armed conflict.[42] Aid can also more directly strengthen the rule of autocratic governments due to the popularity of the idea, challenged by William Easterly, that benevolent autocrats are more successful in promoting economic growth.[43]

The economist William Easterly and others have argued that aid can often distort incentives in poor countries in various harmful ways. Aid can also involve inflows of money to poor countries that have some similarities to inflows of money from natural resources that provoke the resource curse.[44][45] Further, Easterly's criticism highlights the potentially dangerous combination of classic aid and military interventionism. Easterly argues that, for the past twenty-five years, the United States, the United Kingdom, the United Nations and even some international institutions like the World Bank have pushed for “new aid imperialism”.[46]

Even though Easterly is known as a vocal and influential anti-aid figure,[47] the scholar has also recognized that aid agencies can be helpful under certain circumstances. According to Easterly, the agencies must be specific in their goals, avoid giving aid to corrupt autocrats, chose effective channels of aid and minimize administrative costs. The scholar calls attention to the fact that, under this set of goals, multilateral development banks are the most effective aid agencies, whereas United Nation’s agencies are the worst performing organisms [48]

An alternative view from that of Easterly poses that weak institutions, such as frail governance structures, explain recipient countries' frequent failure to accommodate large inflows of aid.[49] In the same line, Pritchett et al. hold that one of the ways in which countries fail to improve their capability -although it is broadly promoted by aid agencies- is when they try to answer to all the external requirements. The problem here is that these countries are not prepared to receive and effectively answer to the excessive pressure from external agents. The result is not only the fail to improve state’s capacity, but also that external engagement can curb national organizations that work well in the context of the country.[50] Likewise, Moss et al. argue that requirements of donors can hinder the daily work of national officials that end up being forced to redefine their priorities around the donor’s interests. These authors present the case of Tanzania in order to illustrate the negative impact of donor's pressure on national weak states. In that country, visits and requirements of donors became so demanding that they had to declare a yearly ‘mission holiday’ of four months in which they can concentrate on budget preparation.[51]

From a different angle, some believe that aid is offset by other economic programs such as agricultural subsidies. Mark Malloch Brown, former head of the United Nations Development Program, estimated that farm subsidies cost poor countries about US$50 billion a year in lost agricultural exports:

It is the extraordinary distortion of global trade, where the West spends $360 billion a year on protecting its agriculture with a network of subsidies and tariffs that costs developing countries about US$50 billion in potential lost agricultural exports. Fifty billion dollars is the equivalent of today's level of development assistance.[52][53]

Rajan and Subramanian also suggest that large levels of foreign aid can lead to negative macroeconomic consequences for local economies, especially affecting the real exchange rate and the competitiveness of the export sector, phenomenon known as Dutch Disease.[54]

James Ferguson and Larry Lohmann argue that foreign aid agencies such as World Bank, sometimes forge “country profiles”, which often bear little or no relation to the recipient countries’ economic and social reality. Development agencies prefer to use standardized development package and the creation of this falsified “country profiles” is to justify aid agencies’ use of such development package. For example, in World Bank’s 1975 report of Lesotho, Lesotho was portrayed as traditional subsistence peasant society and economically isolated. However, this description was inaccurate, Lesotho’s economy was closely integrated into the South African economy and far from being a subsistence society. As the result of this falsified “country profiles”, World Bank’s subsequent development package failed to address the real issue in Lesotho and eventually failed.[55]

Evidence on aid and development

The evidence on the consequence of foreign aid on development is mixed. Various studies find a positive relationship. For instance, Dollar& Burnside (2000)[56] find a positive impact of foreign aid given between 1970 and 1993 in countries with good economic policy and Collier and Dehn (2001)[57] find that foreign aid can be useful to reduce the negative effects of negative export shocks. Galiani et al. (2014)[58] used a regression discontinuity design between countries eligible and non-eligible for the World Bank IDA funds but with similar levels of per capita income to show that, on the frontier, eligible countries have positive impact on economic growth.[lower-alpha 1]

But many countries have also found negative impacts. Easterly et al. (2003) and Easterly (2003)[59] question the positive impacts found by Dollar & Burnside (2000). Roodman (2007)[60] also find that results from seven relevant papers that found a positive impact are sensitive to changes in the specification. Djankov et al (2008) found that aid reduces democracy - measured using the Polity IV index- of the top recipients. Rajan & Subramanian (2011) finds evidence supporting a Dutch disease caused by aid revenues, and Svensson (2000)[61] finds that it augments corruption.[lower-alpha 2]

Support of corrupt state structures

James Shikwati, a Kenyan economist, has argued that foreign aid causes harm to the recipient nations, specifically because aid is distributed by local politicians, finances the creation of corrupt government such as that led by Dr. Fredrick Chiluba in Zambia bureaucracies, and hollows out the local economy. In an interview with Germany's Der Spiegel magazine, Shikwati uses the example of food aid delivered to Kenya in the form of a shipment of corn from America. Portions of the corn may be diverted by corrupt politicians to their own tribes.[62] In an episode of 20/20, John Stossel demonstrated the existence of secret government bank accounts which concealed foreign aid money destined for private purposes. Dambisa Moyo notes the links to corruption of aid flows destined to help the average African by which they end up supporting "bloated bureaucracies in the form of the poor-country governments and donor-funded non-governmental organizations". In a hearing before the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations in May 2004, Jeffrey Winters, professor at Northwestern University, argued that the World Bank had participated in the corruption of roughly $100 billion of its loan funds intended for development. Furthermore, she stated that foreign aid can be a tool for foreign control.[63]

Self-reliance and local infrastructure

James Shikwati also argued that foreign aid causes harm to the recipient nations by hollowing out the local economy. In an interview with Germany's Der Spiegel magazine, Shikwati uses the example of food aid delivered to Kenya in the form of a shipment of corn from America which may be sold on the black market at prices that undercut local food producers. Similarly, Kenyan recipients of donated Western clothing will not buy clothing from local tailors, putting the tailors out of business. According to him development aid weakens the local markets everywhere and dampens the needed spirit of entrepreneurship.[62] Sithembiso Nyoni argues that local resource mobilization is of necessity for development to be sustainable and not dis-empowering and counterproductive.[64]

James Bovard comments on the US Food for Peace program saying that although it sometimes alleviates hunger in the short run, it often disrupts local agricultural markets and makes it harder for poor countries to feed themselves in the long run.[65]

Claudia R. Williamson, Assistant Professor of Economics at Mississippi State University, states that food aid is an ineffective channel of mainly in-kind provision of foods that typically could be purchased much cheaper in recipient local markets.[66]

Aid dependence and Taxation

Tax collection is considered the most basic task for a state. Before a state can protect its citizens, build infrastructure or provide services it needs to develop revenue collection. When analyzing what prevents developing countries from implementing a functioning tax collection system many argue that foreign aid is at fault. Professor Deborah Bräutigam addresses three potential reasons why aid dependence is preventing countries from developing a healthy revenue collection system.[67]

Firstly, large sums of foreign aid inhibit accountability relations between the government and its citizens. Governments develop a responsibility towards the donors when receiving aid but not towards taxpayers, therefore undermining the responsiveness towards citizens. Only when aid is in the form of a loan, and citizens understand that it will be repaid with their taxes, accountability links are fostered. Secondly, aid can affect the legitimacy of a state and this can potentially impact tax revenues therefor creating a vicious circle. When citizens identify that foreign aid sponsored the infrastructure development or health improvements, they might be less likely to pay their taxes and comply with their responsibility as citizens, which would in turn affect the national revenues and the state capacity to invest in development. Finally, foreign aid does not require governments to develop a strong revenue collection capacity. On the contrary, aid needs governments that lack capacity and therefor creates incentives for both donor agency employees and host country employees to resist effective revenue collection capacity building. Taxation on the other hand does require capacity, and as countries move down the scale from simple trade taxes to consumption and income taxes, the demands on capacity rise. This creates an effective stimulus that donor’s conditionality has not been able to provide. Although there are special cases where foreign aid can lead to further development of institutions, as the example of Zambia in the 1990s suggests, most cases indicate that, in fact, there exists a negative association between foreign aid and tax revenue.[67]

Furthermore, in their essay "An Institutions-Aid Paradox? A Review Essay on Aid Dependency and State Building in Sub-Saharan Africa", Moss et al also assert that large quantities of aid given to low-income countries, particularly those in sub-Saharan Africa, undermine the state's ability to collect tax revenues—which, in turn, diminishes its state capacity—which can threaten a state's accountability and legitimacy towards its people. Based on the standard IMF data on government finances, they suggest there is a negative association between foreign aid and tax revenues; when contrasting foreign aid (as a share of GNI) against tax revenue —excluding trades— (as a share of GDP) for the group of 55 countries with low and lower-middle income for the period 1972-1999, results showed there were several cases of low levels of foreign aid and low tax revenue, and moderate number of cases with low levels of foreign aid and high tax revenue, or with high levels of foreign aid and low tax revenue. But there were no cases of high levels of foreign aid and high tax revenue.They ultimately suggest that foreign aid would better be spent on activities such as public good projects, maintaining regional security efforts, and more.[41]

In "Taxation and Development" Besley and Persson (2013) argue that even though it exists a negative relationship between aid and the fiscal capacity of a country, it is very likely that this relationship is endogenous; while increasing aid can reduce a weak state’s incentives to invest in fiscal capacity, aid is frequently targeted to countries that haven’t been able to collect revenue by themselves. Using this argument, the authors conclude that there is not a clear causality between these variables.[68] Moss, Pettersson and Van de Walle (2006), also talk about this paradoxical relationship as one of the arguments of what they call the “aid curse”. They state that, given the amount and quality of the available data, it is impossible to make any conclusions about the direction of the relationship between tax revenues and foreign aid, even though it is clearly negative. They discuss the possibility of other covariates affecting both the levels of tax collection and the amount of aid received like economic activity and the level of industrialization of a country.[69]

Ulterior agendas

The idea that aid is given for a number of ulterior agendas is supported by the academic literature. In a study co-authored by the World Bank, the authors use data on bilateral aid flows reported by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to scrutinize foreign aid, mainly from US, Japan, and France.[70] The study finds that foreign aid decisions by these countries are governed by varying strategic or political factors; such as colonial history for France, business ties for Japan, and influence in the Middle East for the US. This is further discussed in another study that uses selectorate theory to explain foreign aid giving.[71] The authors argue the size of the leader’s support coalition in the recipient government, ranging from the general public to a narrow elite-filled coalition, is an important factor in aid granting in OECD countries. Governments with narrower coalitions can more easily make concessions to the aid providing state. The study uses bilateral aid transfers from 1960 to 2001 by OECD states as evidence that some countries in fact do give to governments that are better at granting concessions and can be more easily influenced.

Aid is seldom given from motives of pure altruism; for instance it is often given as a means of supporting an ally in international politics. It may also be given with the intention of influencing the political process in the receiving nation. Whether one considers such aid helpful may depend on whether one agrees with the agenda being pursued by the donor nation in a particular case. During the conflict between communism and capitalism in the twentieth century, the champions of those ideologies – the Soviet Union and the United States – each used aid to influence the internal politics of other nations, and to support their weaker allies. Perhaps the most notable example was the Marshall Plan by which the United States, largely successfully, sought to pull European nations toward capitalism and away from communism. Aid to underdeveloped countries has sometimes been criticized as being more in the interest of the donor than the recipient, or even a form of neocolonialism.[72] One such example can be seen in the criticisms of the Green Revolution.[73]

S.K.B'. Asante lists some specific motives a donor may have for giving aid: defence support, market expansion, foreign investment, missionary enterprise, cultural extension.[74] In recent decades, aid by organizations such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank has been criticized as being primarily a tool used to open new areas up to global capitalists, and being only secondarily, if at all, concerned with the wellbeing of the people in the recipient countries.

The aid-paradox

Moss et al. (2004) argue that foreign aid weakens the relationship between the citizens and the government. Foreign aid makes governments accountable to external agencies, both in the design and output of the projects. As a result, it reduces ownership, civic participation and accountability, the theoretical aims of aid in the first place. There are various channels through which this effect consolidates: i) governments underinvest in state capacity because its revenue flows do not depend on its efficiency; ii) governments are less likely to advocate and explain policy decisions; iii) there is no ownership of the policies because the decisions are taken by external agencies, thus, there are fewer incentives to engage in civic action, and iv) even when governments are held accountable by donors, the latter’s mechanisms do not replace citizen participation.

Political Aid Cycles

Faye and Niehaus (2012) find that the amount of foreign aid received might increase during elections if the donor is politically aligned with the incumbent or his party. Moreover, these political aid cycles seem to be driven by bilateral aid and competitive elections.

For their analysis, Faye and Niehaus (2012) compare aid flows in election and non-election years in countries where the donor might want to turn elections in favor of the government's party candidate. They use 30 year ODA data and focus in the five largest donors (United States, Japan, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom), that account for 77% of all aid commitments, and an average of 102 country recipients.[75]

Unbalanced Distribution of Aid

The distribution of aid seems not to be balanced. Qian (2014)[76] points out that the poorest 20% countries of the world received only 1.69-5.25% of the total ODA in each year since 1960. Some studies show that aid can be affected by various factors such as the donor countries' ideological interests, economic strategies[77] or historical background especially former colonial ties[78] rather than by humanitarian criteria, which may be one of the reasons of this uneven distribution.

Negative views

In November 2012, a spoof charity music video was produced by a South African rapper named Breezy V. The video “Africa for Norway” was a parody of Western charity initiatives like Band Aid which, he felt, exclusively encouraged small donations to starving children, creating a stereotypically negative view of the continent.[79] Aid in his opinion should be about funding initiatives and projects with emotional motivation as well as money. The parody video shows Africans getting together to campaign for Norwegian people suffering from frostbite by supplying them with unwanted radiators.[79]

The "aid industry"

Private giving includes aid from charities, philanthropic organizations or businesses to recipient countries or programs within recipient countries. Garrett has observed that aid donor organizations have developed their own industry known as the "aid industry". Private donors to countries in need of aid are a large part of this, by making money while finding the next best solution for the country in need of aid. These private outside donors take away from local entrepreneurship leaving countries in need of aid reliant on them.[29]

Some have argued that the major international aid organizations have formed an aid cartel.[80]

Reform movements

In the United States

In response to aid critics, a movement to reform U.S. foreign aid has started to gain momentum. In the United States, leaders of this movement include the Center for Global Development, Oxfam America, the Brookings Institution, InterAction, and Bread for the World. The various organizations have united to call for a new Foreign Assistance Act, a national development strategy, and a new cabinet-level department for development.[81]

Beyond aid

As a result of these numerous criticisms, other proposals for supporting developing economies and poverty stricken societies. Some analysts, such as researchers at the Overseas Development Institute, argue that current support for the developing world suffers from a policy incoherence and that while some policies are designed to support the third world, other domestic policies undermine its impact,[82] examples include:

- encouraging developing economies to develop their agriculture with a focus on exports is not effective on a global market where key players, such as the US and EU, heavily subsidise their products

- providing aid to developing economies' health sectors and the training of personnel is undermined by migration policies in developed countries that encourage the migration of skilled health professionals

One measure of this policy incoherence is the Commitment to Development Index (CDI) published by the Center for Global Development . The index measures and evaluates 22 of the world's richest countries on policies that affect developing countries, in addition to simply aid. It shows that development policy is more than just aid; it also takes into account trade, investment, migration, environment, security, and technology.

Thus, some states are beginning to go beyond aid and instead seek to ensure there is a policy coherence, for example see Common Agricultural Policy reform or Doha Development Round. This approach might see the nature of aid change from loans, debt cancellation, budget support etc., to supporting developing countries. This requires a strong political will, however, the results could potentially make aid far more effective and efficient.[82]

According to Michael Matheson Miller "We should not be working to alleviate poverty through donations. We should instead focus on the conditions that enable people to generate wealth."[83]

Transition out of aid

Researchers looked at how Ghana compares with groups of other countries that have been transitioning out of aid. They talk about how the World Bank reclassified Ghana from a low income country to a lower middle income country in 2010. They found Ghana experiencing significant improvements across development indicators since early 2000s with different changes for different indicators which is consistent or better than lower middle income country averages.[84]

Academic theories

Since the 1960s, improving the efficiency of foreign aid has been a common topic of academic research. There is debate on whether foreign aid is efficacious, but for the purposes of this article we will ignore that. Given that schema, a common debate is over which factors influence the overall economic efficiency of foreign aid. Indeed, there is debate about whether aid impact should be measured empirically at all, but again, we will limit our scope to increasing the economic efficiency.

At the forefront of the aid debate has been the conflict between professor William Easterly of New York University [85] and his ideological opposite, Jeffrey Sachs, from Columbia University. Easterly advocates the "searcher's" approach, while Sachs advocates a more top down, broad planned approach. We will discuss both of these at length.[86]

“Searchers Approach”

William Easterly offers a nontraditional, and somewhat controversial "searching" approach to dealing with poverty, as opposed to the "planned" approach in his famous critique of the more traditional Owen/Sachs, The White Man’s Burden. Traditional poverty reduction, Easterly claims is based on the idea that we know what is best for impoverished countries. He claims that they know what’s best. Having a top down “master plan,” he claims, is inefficient. His alternative, called the “Searchers” approach, uses a bottom up strategy. That is, this approach starts by surveying the poor in the countries in question, and then tries to directly aid individuals, rather than governments. Local markets are a key incentive structure. The primary example is of mosquito nets in Malawi. In this example, an NGO sells mosquito nets to rich Malawians, and uses the profits to subsidize cheap sales to the impoverished. Hospital nurses are used as middle-women, profiting a few cents on every net sold to a patient. This incentive structure has seen the usage of nets in Malawi spike over 40% in less than 7 years.[87]

One of the central tenets in Easterly’s approach is a more bottom up philosophy of aid. This applies not only to the identification of problems, but to the actual distribution of capital to the areas in need. In effect, Easterly would have countries go to the area which needed aid, collect information about the problem, find out what the population wanted, and then work from there. In keeping with this, funds would also be distributed from the bottom up, rather than being given to a specific government.[87]

Easterly also advocates working through currently existing Aid organizations, and letting them compete for funding. Utilizing pre-existing national organizations and local frameworks would not only help give target populations a voice in implementation and goal setting, but is more efficient economically. Easterly argues that the preexisting frameworks already "know" what the problems are, as opposed to outside NGOs who tend to "guess".[87]

Easterly strongly discourages aid to government as a rule. He believes, for several reasons, that aid to small “bottom up” organizations and individual groups is a better philosophy than to large governments.[87]

Easterly states that for far too long, inefficient aid organizations have been funded, and that this is a problem. The current system of evaluation for most aid organizations is internal. Easterly claims that the process is biased because organizations have a large incentive to represent their progress in a positive light. What he proposes as an alternative is an independent auditing system for aid organizations. Before receiving funding, the organization would state their goals and how they expect to measure and achieve them. If they do not meet their goals, Easterly proposes we shift our funding to organizations who are successful. This would prompt organizations to either become efficient, or obsolete.[87]

Easterly believes that aid goals should be small. In his opinion, one of the main failings of aid lies in the fact that we create large, utopian lists of things we hope to accomplish, without the means to actually see them to fruition. Rather than establish a utopian vision for a particular country, Easterly insists that we shift our focus to the most basic needs and improvements. If we feed, clothe, vaccinate, build infrastructure, and support markets, the macroscopic results will follow.[87]

The “Searching Approach” is intrinsically tied to the market. Easterly claims that the only way for poverty to truly end is for the poor to be given the capability to lift themselves out of poverty, and then for it to happen. Philosophically, this sounds like the traditional “bootstrap” theory, but it isn’t. What he says is that the poor should be given the fiscal support to create their market, which would give them the ability to become self-reliant in the future.[87]

In the end of his book, Easterly proposes a voucher system for foreign aid. The poor would be distributed a certain amount of vouchers, which would act as currency, redeemable to aid organizations for services, medicines, and the like. These vouchers would then be redeemed by the aid organizations for more funding. In this way, the aid organization would be forced to compete, if by proxy.[87]

Proscriptive "Ladder Approach"

Sachs presents a near dichotomy to Easterly. Sachs presents a broad, proscriptive solution to poverty. In his book, The End of Poverty, he explains how throughout history, countries have ascended from poverty by following a relatively simple model. First, you promote agricultural development, then industrialize, embrace technology, and finally become modern. This is the standard “western” model of development that has been followed by countries such as China and Brazil. Sachs main idea is that there should be a broad analytical “checklist” of things a country must attain before it can reach the next step on the ladder to development. Western nations should donate a percentage of their GDP as determined by the UN, and pump money into helping impoverished countries climb the ladder. Sachs insists that if followed, his strategy would eliminate poverty by 2025.[88]

Sachs advocates using a top down methodology, utilizing broad ranging plans developed by external aid organizations like the UN and World Bank. To Sachs, these plans are essential to a coherent and timely eradication of poverty. He surmises that if donor and recipient countries follow the plan, they will be able to climb out of poverty.[88]

Part of Sachs’ philosophy includes strengthening the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and the United Nations. If those institutions are given the power to enact change, and freed from mitigating influences, then they will be much more effective. Sachs does not find fault in the international organizations themselves. Instead, he blames the member nations who compose them. The powerful nations of the world must make a commitment to end poverty, then stick to it.[88]

Sachs believes it is best to empower countries by utilizing their existing governments, rather than trying to circumnavigate them. He remarks that while the corruption argument is logically valid in that corruption harms the efficiency of aid, levels of corruption tend to be much higher on average for countries with low levels of GDP. He contends that this hurdle in government should not disqualify entire populations for much needed aid from the west.[88]

Sachs does not see the need for independent evaluators, and sees them as a detractor to proper progress. He argues that many facets of aid cannot be effectively quantified, and thus it is not fair to try to put empirical benchmarks on the effectiveness of aid.[88]

Sachs’ view makes it a point to attack and attempt to disprove many of the ideas that the more “pessimistic” Easterly stands on.

First, he points to economic freedom. One of the common threads of logic in aid is that countries need to develop economically in order to rise from poverty. On this, there is not a ton of debate. However, Sachs contends that Easterly, and many other neo-Liberal economists believe high levels of economic freedom in these emerging markets is almost a necessity to development. Sachs himself does not believe this. He cites the lack of correlation between the average degrees of Economic Freedom in countries and their yearly GDP growth, which in his data set is completely inconclusive.

Also, Sachs contends that democratization is not an integral part of having efficient aid distribution. Rather than attach strings to our aid dollars, or only working with democracies or “good governments”, Sachs believes we should consider the type of government in the needy country as a secondary concern.

Sachs’ entire approach stands on the assertion that abject poverty could be ended worldwide by 2025.[88]

David Dollar

Dollar/Collier showed that current allocations of aid are inefficient. They came to the conclusion that aid money is given in many cases as an incentive to change policy, and for political reasons, which in many cases can be less efficient than the optimal condition. They agree that bad policy is detrimental to economic growth, which is a key component of poverty reduction, but have found that aid dollars do not significantly incentivize governments to change policy. In fact, they have negligible impact. As an alternative, Dollar proposes that aid be funneled more towards countries with “good” policy and less than optimal amounts of aid for their massive amounts of poverty. With respect to “optimal amounts” Dollar calculated the marginal productivity of each additional dollar of foreign aid for the countries sampled, and saw that some countries had very high rates of marginal productivity (each dollar went further), while others [with particularly high amounts of aid, and lower levels of poverty] had low [and sometimes negative] levels of marginal productivity. In terms of economic efficiency, aid funding would be best allocated towards countries whose marginal productivities per dollar were highest, and away from those countries who had low to negative marginal productivities. The conclusion was that while an estimated 10 million people are lifted from poverty with current aid policies, that number could be increased to 19 million with efficient aid allocation.[89]

“New Conditionality”

New Conditionality is the term used in a paper to describe somewhat of a compromise between Dollar and Hansen. Paul Mosely describes how policy is important, and that aid distribution is improper. However, unlike Dollar, “New Conditionality” claims that the most important factors in efficiency of aid are income distributions in the recipient country and corruption.[90]

McGillivray

One of the problems in foreign aid allocation is the marginalization of the fragile state. The fragile state, with its high volatility, and risk of failure scares away donors. The people of those states feel harm and are marginalized as a result. Additionally, the fate of neighboring states is important, as economies of the directly adjacent states to those impoverished, volatile “fragile states” can be negatively impacted by as much as 1.6% of their GDP per year. This is no small figure. McGillivray advocates for the reduced volatility of aid flows, which can only be attained through analysis and coordination.[91]

Aid on the Edge of Chaos

A persistent problem in foreign aid is what some have called a 'neo-Newtonian' paradigm for thinking and action. Development and humanitarian problems are frequently dealt with as if they are simple, linear, and best addressed through the application of 'best practices' developed in Western countries and then applied ad infinitum by aid agencies. This approach has come under sustained criticism in Ben Ramalingam's Aid on the Edge of Chaos. This work advocates that aid agencies should embrace the ideas and principles of complex adaptive systems research in order to improve how they think about and act on development problems.

See also

Nations:

- Australian Agency for International Development

- China foreign aid

- Department for International Development (United Kingdom)

- International economic cooperation policy of Japan

- Saudi foreign assistance

- Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency

- United States foreign aid

Notes

Notes and references

- 1 2 Lancaster, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Lancaster, p. 67: "In 1957 the administration (with congressional support) separated economic from military assistance and created a Development Loan Fund (DLF) to provide concessional credits to developing countries world-wide (i.e. not, as in the past, just those in areas of potential conflict with Moscow) to promote their long-term growth.

- ↑ Carol Lancaster. Foreign Aid. 2007. p.9.

- ↑ Carol Lancaster. Foreign Aid. 2007. p.13.

- 1 2 3 4 "Aid to developing countries rebounds in 2013 to reach an all-time high". OECD. 8 April 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ↑ "Net official development assistance and official aid received (current US$)". World Development Indicators. World Bank. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- ↑ "Development and cooperation". European Union. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ↑ Securing Tyrants or Fostering Reform?: U.S. Internal Security Assistance to Repressive and Transitioning Regimes. The RAND Corporation. 2006. ISBN 978-0-8330-4018-3.

- ↑ Defining humanitarian assistance. Global Humanitarian Assistance. 2014.

- ↑ Bush brings faith to foreign aid. The Boston Globe. 8 October 2006.

- 1 2 Lancaster uses either ODA or ODA plus OA ("Official Assistance" – another DAC government-aid category) as her main statistic. She considers it better to add the OA but very often just uses the ODA figure alone; e.g., for Table 1.1 (p. 13), Table 2.2 (p. 39) and Table 2.3 (p. 43). In any case the difference is now moot since the DAC recently merged the two categories.

- ↑ "Official development assistance – definition and coverage". OECD. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ N; Baruah, ita; Arjal, Nischala (30 November 2011). "Giving Foreign Aid Helps Korea". Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- 1 2 "Migration and development: The aid workers who really help". economist.com. 8 October 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- 1 2 "Tied aid strangling nations, says UN". ispnews.net. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ↑ "Aid policy: Helping whom exactly?". economist.com. 27 April 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ "Let them eat micronutrients". newsweek.com. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "The future of aid". economist.com. 6 September 2008. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ↑ "Food aid reform". Oxfam America.

- 1 2 Dugger, Celia W. (2 December 2007). "Ending famine simply by ignoring the experts". nytimes.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ↑ "Study Finds Poverty Deepening in Former Communist Countries". nytimes.com. 12 October 2000. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ↑ Transition: The First Ten Years – Analysis and Lessons for Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union, The World Bank, Washington, DC, 2002, p. 4.

- ↑ "Child poverty soars in eastern Europe". BBC News. 11 October 2000. Archived from the original on 18 July 2004. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ↑ "Good Governance and Aid Effectiveness: The World Bank and Conditionality" by CARLOS SANTISO in the Georgetown Public Policy Review, 2001. http://www.sti.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/Pdfs/swap/swap108.pdf

- 1 2 "Doing cash differently: how cash transfers can transform humanitarian aid". Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- 1 2 Crilly, Rob (4 June 2008). "UN aid debate: Give cash, not food?". Retrieved 14 July 2017 – via Christian Science Monitor.

- 1 2 Rosenberg, Tina (24 April 2013). "When food isn't the answer to hunger". nytimes.com. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ Cash roll-out to help hunger hot spots Archived 12 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 Garrett, Laurie. "The Challenge of Global Health". Foreign Affairs. 86 (1).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sachs, Jeffrey D. 2005. The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time. New York: Penguin Books.

- 1 2 3 Singer, Peter. 2009. The Life You Can Save. New York:Random House.

- ↑ Collier, Paul. 2007. The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries are Failing and What Can Be Done About It. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Habibzadeh, Yadollahie, Kucheki (2008). International aid in disaster zones: help or headache? Lancet.

- ↑ Lindsay Falvey (2016) Integrated Development. http://www.self.gutenberg.org/wplbn0004450835-integrated-development-by-falvey-john-lindsay-dr-.aspx?

- 1 2 Cabral and Weinstock 2010. Brazil: an emerging aid player. London: Overseas Development Institute

- ↑ Cabral, Lidia 2010. Brazil’s development cooperation with the South: a global model in waiting Archived 30 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine.. London: Overseas Development Institute

- ↑ Steven Radelet, The Great Surge: The Ascent of the Developing World (2015) pp 209–30

- ↑ Katarina Juselius, Niels Framroze Møller, and Finn Tarp. "The Long‐Run Impact of Foreign Aid in 36 African Countries: Insights from Multivariate Time Series Analysis." Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 76.2 (2014): 153–184.

- ↑ Dreher, Axel, Vera Eichenauer, Kai Gehring, Sarah Langlotz, Steffen Lohmann, 2015, Does foreign aid affect growth? VoxEU, 18 October 2015.

- ↑ Asante, p. 265.

- 1 2 Moss, Todd; Pettersson, Gunilla; van de Walle, Nicolas (January 2006). "An Aid-Institutions Paradox? A Review Essay on Aid Dependency and State Building in Sub-Saharan Africa" (PDF). Center for Global Development. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ↑ Nunn, Nathan; Qian, Nancy (2014). "US Food Aid and Civil Conflict" (PDF). American Economic Review. 104 (6): 1630–1666.

- ↑ Easterly, William (May 2011). "Benevolent Autocrats" (PDF). Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ↑ Collier, Paul (2005). Is Aid Oil? An analysis of whether Africa can absorb more aid. Centre for the study of African Economies, Oxford University.

- ↑ Djankov, Montalvo, Reynal-Querol (2005). The curse of aid. The World Bank.

- ↑ Easterly, William (December 2008). "Foreign Aid Goes Military!". New York Review of Books. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ↑ Banerjee, Abhijit and Esther Duflo (April 2011). “Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Poverty" p. 3.

- ↑ Easterly, William and Tobias Pfutze (2008). "Where Does the Money Goes? Best and Worst Practices in Foreign Aid" Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22 (2).

- ↑ Auer, Matthew. "More Aid, Better Institutions, or Both?" Sustainability Science 2 (2007): 179–187.

- ↑ Pritchett, Lant, Michael Woolcock, and Matt Andrews. 2013. “Looking like a state: techniques of persistent failure in state capability for implementation.” The Journal of Development Studies 49(1): 1-18.

- ↑ Moss, Todd, Gunilla Pettersson, and Nicolas Van de Walle. 2006. “An aid-institutions paradox? A review essay on aid dependency and state building in sub-Saharan Africa.” Center for Global Development Working Paper 74.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 July 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2009. Address by Mark Malloch Brown, UNDP Administrator, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda, 12 November 2002

- ↑ "Farm Subsidies That Kill", July 5, 2002, By NICHOLAS D. KRISTOF, New York Times

- ↑ Rajan, Raghuram; Subramanian, Arvind. "What Undermines Aid's Impact on Growth?" (PDF). doi:10.3386/w11657.

- ↑ Ferguson, James. "The Anti-Politics Machine" (PDF). colorado.edu.

- ↑ Burnside, Craig; Dollar, David (2000). "Aid, Policies, and Growth". The American Economic Review. 90 (4): 847–868.

- ↑ Collier, Paul Collier, Paul Dehn, Jan (2001-10-01). Aid, Shocks, and Growth. Policy Research Working Papers. The World Bank. doi:10.1596/1813-9450-2688.

- ↑ Sebastian, Galiani,; Stephen, Knack,; Ben, Zou,; Colin, Xu, Lixin (2014-05-01). "The effect of aid on growth : evidence from a quasi-experiment".

- ↑ Easterly, William (2003). "Can Foreign Aid Buy Growth?". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 17 (3): 23–48.

- ↑ Roodman, David (2007-01-01). "The Anarchy of Numbers: Aid, Development, and Cross-Country Empirics". The World Bank Economic Review. 21 (2): 255–277. ISSN 0258-6770. doi:10.1093/wber/lhm004.

- ↑ Svensson, Jakob (2000). "Foreign aid and rent-seeking". Journal of International Economics. 51 (2): 437–461. ISSN 0022-1996.

- 1 2 Thilo Thielke (interviewer), translated by Patrick Kessler. "For God's Sake, Please Stop the Aid!"

- ↑ Moyo, Dambisa (22 March 2009). "Why Foreign Aid Is Hurting Africa". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ Holloway, Richard. Towards Financial Self-reliance: A Handbook on Resource Mobilization for Civil Society Organizations in the South. Earthscan. ISBN 9781853837739. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ "Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 65: The Continuing Failure of Foreign Aid" (PDF). Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ Williamson, Claudia R. (11 July 2009). "Exploring the failure of foreign aid: The role of incentives and information" (PDF). The Review of Austrian Economics. 23 (1): 17–33. doi:10.1007/s11138-009-0091-7. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- 1 2 Bräutigam, Deborah (2002). "Building Leviathan: Revenue, State Capacity and Governance" (PDF). IDS Bulletin. 33 (3). Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- ↑ Besley, Timothy, and Torsten Persson. 2013. “Taxation and Development.” Handbook of Public Economics 5: 51.

- ↑ Moss, Todd, Pettersson Gelander, Gunilla and van de Walle, Nicolas, (2006), An Aid-Institutions Paradox? A Review Essay on Aid Dependency and State Building in Sub-Saharan Africa, No 74, Working Papers, Center for Global Development, http://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:cgd:wpaper:74.

- ↑ Alesina, Alberto; Dollar, David (2000). "Who Gives Foreign Aid to Whom and Why?". Journal of Economic Growth. 5 (1): 33–63.

- ↑ Mesquita, Bruce Bueno de; Smith, Alastair (2009-04-01). "A Political Economy of Aid". International Organization. 63 (2): 309–340. ISSN 1531-5088. doi:10.1017/S0020818309090109.

- ↑ S.K.B. Asante, "International Assistance and International Capitalism: Supportive or Counterproductive?", in Gwendolyn Carter and Patrick O'Meara (eds) African Independence: The First Twenty-Five Years, 1985; Bloomington, Indiana, USA; Indiana University Press. p. 249.

- ↑ Clapp, Jennifer (2012). Food. Polity. pp. ch. 2. ISBN 9780745649351.

- ↑ Asante, p. 251.

- ↑ Faye, Michael; Niehaus, Paul (December 2012). "Political Aid Cycles". The American Economic Review. 102: 3516–3530.

- ↑ Qian N. 2014. Making Progress on Foreign Aid. Annu. Rev. Econ. 3: Submitted. Doi:10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115553

- ↑ Schraeder P J, Hook S W, Taylor B. 1998. Clarifying the Foreign Aid Puzzle: A Comparison of American, Japanese, French, and Swedish Aid Flows. World Pol. 50:294–323

- ↑ Nunn N, Qian N. 2014. The Determinants of Food Aid Provisions to Africa and the Developing World. In: S. Edwards, S. Johnson and D. Weil, ed., National Bureau of Economic Research Conference Report: African Successes, Volume IV Sustainable Growth: University of Chicago Press

- 1 2 "Africa: Why Are Africans for Norway?". Africa: AllAfrica.com. 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2012

- ↑ The cartel of good intentions, Foreign Policy, Washington, Jul/Aug 2002, Authors: William Easterly, Issue: 131, Pagination: 40–49, ISSN 0015-7228

- ↑ Loewenberg, Samuel (10 June 2008) Coalition seeks cabinet-level foreign aid. Politico.com. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- 1 2 Alan Hudson and Linnea Jonsson (2009) ‘Beyond Aid’ for sustainable development London: Overseas Development Institute

- ↑ Meyer, Jared. "Foreign Aid's Real Winners Aren't The Poor". Forbes. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ Zhenbo Hou and Jane Kennan, Graduation out of aid research, ECONOMIC AND PRIVATE SECTOR PROFESSIONAL EVIDENCE AND APPLIED KNOWLEDGE SERVICES, http://www.partnerplatform.org/?kr890w41

- ↑ "About". William Easterly. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ↑ http://www.earth.columbia.edu/articles/view/1770

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Easterly, William (2007). The White Man's Burden. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-922611-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sachs, Jeffrey (2005). The End of Poverty. Penguin Group.

- ↑ "Aid allocation and poverty reduction". European Economic Review. 46: 1475–1500. doi:10.1016/S0014-2921(01)00187-8.

- ↑ Mosley, Paul; Hudson, John; Verschoor, Arjan (1 June 2004). "Aid, Poverty Reduction and the ‘New Conditionality’*". The Economic Journal. 114 (496): F217–F243. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2004.00220.x. Retrieved 14 July 2017 – via Wiley Online Library.

- ↑ http://www.ineesite.org/uploads/documents/store/doc_1_Aid_Allocation_and_FS.pdf

- Håkan Malmqvist (2000), Development Aid, Humanitarian Assistance and Emergency Relief, Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Sweden.

- Andrew Rogerson with Adrian Hewitt and David Waldenberg (2004), The International Aid System 2005–2010 Forces For and Against Change, ODI Working Paper 235.

- Easterly, William (2006). The White Man's Burden: Why the West's Effort to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good. Penguin. ISBN 1-59420-037-8.

- Anup Shah, US and Foreign Aid Assistance, GlobalIssues.org, Last updated: Sunday, 27 April 2008.

- Millions Saved A compilation of case studies of successful foreign assistance by the Center for Global Development.

- ActionAid, May 2005, "Real Aid" – analysis of the proportion of aid wasted on consultants, tied aid, etc.

- Mousseau, Frederic; Mittal, Anuradha. "Food Sovereignty: Ending World Hunger in Our Time". The Humanist. 2006: 35–40.

- Lancaster, Carol; Van Dusen, Ann (2005). Organizing Foreign Aid: Confronting the Challenges of the 21st Century. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 0-8157-5113-3.

- Ali, Abdiweli M.; Said Isse, Hodan (2007). "Foreign Aid and Free Trade and their Effect on Income: A Panel Analysis". The Journal of Developing Areas. 41 (1): 127–142. doi:10.1353/jda.2008.0016.

Further reading

- Calderisi, Robert (2006). The Trouble with Africa: Why Foreign Aid Isn't Working. Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-7125-0.

- Oxfam America (2008). Smart Development: Why US foreign aid demands major reform. Oxfam America, Inc.

- The cartel of good intentions, Foreign Policy, Washington, Jul/Aug 2002, Authors: William Easterly, Issue: 131, Pagination: 40–49, ISSN 0015-7228

- Development Assistance Committee, Glossary, OECD, Paris.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Aid |