Taxonomic rank

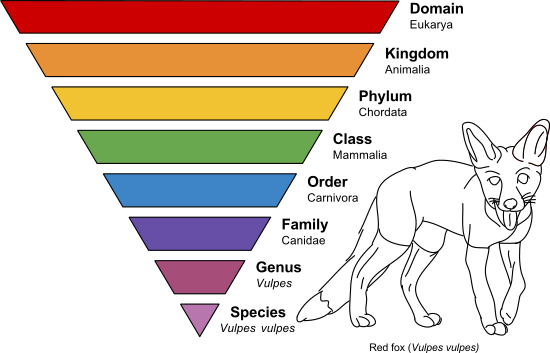

In biological classification, taxonomic rank is the relative level of a group of organisms (a taxon) in a taxonomic hierarchy. Examples of taxonomic ranks are species, genus, family, order, class, phylum, kingdom, domain, etc.

A given rank subsumes under it less general categories, that is, more specific descriptions of life forms. Above it, each rank is classified within more general categories of organisms and groups of organisms related to each other through inheritance of traits or features from common ancestors. The rank of any species and the description of its genus is basic; which means that to identify a particular organism, it is usually not necessary to specify ranks other than these first two.[2]

Consider a particular species, the red fox, Vulpes vulpes: its next rank, the genus Vulpes, comprises all the 'true foxes'. Their closest relatives are in the immediately higher rank, the family Canidae, which includes dogs, wolves, jackals, all foxes, and other caniforms such as bears, badgers and seals; the next higher rank, the order Carnivora, includes feliforms and caniforms (lions, tigers, hyenas, wolverines, and all those mentioned above), plus other carnivorous mammals. As one group of the class Mammalia, all of the above are classified among those with backbones in the Chordata phylum rank, and with them among all the animals in the Animalia kingdom rank. Finally, all of the above will find their earliest relatives somewhere in their domain rank Eukarya.

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature defines rank as:

- The level, for nomenclatural purposes, of a taxon in a taxonomic hierarchy (e.g. all families are for nomenclatural purposes at the same rank, which lies between superfamily and subfamily)[3]

Main ranks

In his landmark publications, such as the Systema Naturae, Carl Linnaeus used a ranking scale limited to: kingdom, class, order, genus, species, and one rank below species. Today, nomenclature is regulated by the nomenclature codes. There are seven main taxonomic ranks: kingdom, phylum or division, class, order, family, genus, species. In addition, the domain (proposed by Carl Woese) is now widely used as one of the fundamental ranks, although it is not mentioned in any of the nomenclature codes. Also, this term represents a synonym for the category of dominion (lat. dominium), introduced by Moore in 1974.[4] Unlike Moore, Whoese et al. (1990) did not suggest a Latin term for this category, which represents a further argument supporting the accurately introduced term dominion.[5]

| Main taxonomic ranks | |

| Latin | English |

| vitae | life |

| regio | domain |

| regnum | kingdom |

| phylum | phylum (in zoology) |

| classis | class |

| ordo | order |

| familia | family |

| genus | genus |

| species | species |

A taxon is usually assigned a rank when it is given its formal name. The basic ranks are species and genus. When an organism is given a species name it is assigned to a genus, and the genus name is part of the species name.

The species name is also called a binomial, that is, a two-term name. For example, the zoological name for the human species is Homo sapiens. This is usually italicized in print and underlined when italics are not available. In this case, Homo is the generic name and it is capitalized; sapiens indicates the species and it is not capitalized.

Ranks in zoology

There are definitions of the following taxonomic ranks in the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature: superfamily, family, subfamily, tribe, subtribe, genus, subgenus, species, subspecies.

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature divides names into "family-group names", "genus-group names" and "species-group names". The Code explicitly mentions:

- Superfamily

The rules in the Code apply to the ranks of superfamily to subspecies, and only to some extent to those above the rank of superfamily. In the "genus group" and "species group" no further ranks are allowed. Among zoologists, additional terms such as species group, species subgroup, species complex and superspecies are sometimes used for convenience as extra, but unofficial, ranks between the subgenus and species levels in taxa with many species (e.g. the genus Drosophila).

At higher ranks (family and above) a lower level may be denoted by adding the prefix "infra", meaning lower, to the rank. For example, infraorder (below suborder) or infrafamily (below subfamily).

Names of zoological taxa

- A taxon above the rank of species has a scientific name in one part (a uninominal name).

- A species has a name composed of two parts (a binomial name or binomen): generic name + specific name; for example Canis lupus.

- A subspecies has a name composed of three parts (a trinomial name or trinomen): generic name + specific name + subspecific name; for example Canis lupus familiaris. As there is only one possible rank below that of species, no connecting term to indicate rank is needed or used.

Ranks in botany

According to Art 3.1 of the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN) the most important ranks of taxa are: kingdom, division or phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. According to Art 4.1 the secondary ranks of taxa are tribe, section, series, variety and form. There is an indeterminate number of ranks. The ICN explicitly mentions:[6]

primary ranks

- secondary ranks

- further ranks

kingdom (regnum)

- subregnum

division or phylum (divisio, phylum)

- subdivisio or subphylum

class (classis)

- subclassis

order (ordo)

- subordo

family (familia)

- subfamilia

- tribe (tribus)

- subtribus

genus (genus)

- subgenus

- section (sectio)

- subsection

- series (series)

- subseries

species (species)

- subspecies

- variety (varietas)

- subvarietas

- form (forma)

- subforma

There are definitions of the following taxonomic categories in the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants: cultivar group, cultivar, grex.

The rules in the ICN apply primarily to the ranks of family and below, and only to some extent to those above the rank of family. Also see descriptive botanical names.

Names of botanical taxa

Taxa at the rank of genus and above have a botanical name in one part (unitary name); those at the rank of species and above (but below genus) have a botanical name in two parts (binary name); all taxa below the rank of species have a botanical name in three parts (an infraspecific name). To indicate the rank of the infraspecific name, a "connecting term" is needed. Thus Poa secunda subsp. juncifolia, where "subsp." is an abbreviation for "subspecies", is the name of a subspecies of Poa secunda.

Hybrids can be specified either by a "hybrid formula" that specifies the parentage, or may be given a name. For hybrids getting a hybrid name, the same ranks apply, prefixed with notho (Greek: 'bastard'), with nothogenus as the highest permitted rank.

Outdated names for botanical ranks

If a different term for the rank was used in an old publication, but the intention is clear, botanical nomenclature specifies certain substitutions:

- If names were "intended as names of orders, but published with their rank denoted by a term such as": "cohors" [Latin for "cohort";[7] see also cohort study for the use of the term in ecology], "nixus", "alliance", or "Reihe" instead of "order" (Article 17.2), they are treated as names of orders.

- "Family" is substituted for "order" (ordo) or "natural order" (ordo naturalis) under certain conditions where the modern meaning of "order" was not intended. (Article 18.2)

- "Subfamily is substituted for "suborder" (subordo) under certain conditions where the modern meaning of "suborder" was not intended. (Article 19.2)

- In a publication prior to 1 January 1890, if only one infraspecific rank is used, it is considered to be that of variety. (Article 37.4) This commonly applies to publications that labelled infraspecific taxa with Greek letters, α, β, γ, ...

Examples

Classifications of five species follow: the fruit fly so familiar in genetics laboratories (Drosophila melanogaster), humans (Homo sapiens), the peas used by Gregor Mendel in his discovery of genetics (Pisum sativum), the "fly agaric" mushroom Amanita muscaria, and the bacterium Escherichia coli. The eight major ranks are given in bold; a selection of minor ranks are given as well.

| Rank | Fruit fly | Human | Pea | Fly agaric | E. coli |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Eukarya | Eukarya | Eukarya | Eukarya | Bacteria |

| Kingdom | Animalia | Animalia | Plantae | Fungi | Bacteria |

| Phylum or Division | Arthropoda | Chordata | Magnoliophyta (Tracheophyta) | Basidiomycota | Proteobacteria |

| Subphylum or subdivision | Hexapoda | Vertebrata | Magnoliophytina (Euphyllophytina) | Agaricomycotina | |

| Class | Insecta | Mammalia | Magnoliopsida (Equisetopsida) | Agaricomycetes | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Subclass | Pterygota | Theria | Rosidae (Magnoliidae) | Agaricomycetidae | |

| Superorder | Euarchontoglires | Rosanae | |||

| Order | Diptera | Primates | Fabales | Agaricales | Enterobacteriales |

| Suborder | Brachycera | Haplorrhini | Fabineae | Agaricineae | |

| Family | Drosophilidae | Hominidae | Fabaceae | Amanitaceae | Enterobacteriaceae |

| Subfamily | Drosophilinae | Homininae | Faboideae | Amanitoideae | |

| Genus | Drosophila | Homo | Pisum | Amanita | Escherichia |

| Species | D. melanogaster | H. sapiens | P. sativum | A. muscaria | E. coli |

- Table notes

- The ranks of higher taxa, especially intermediate ranks, are prone to revision as new information about relationships is discovered. For example, the flowering plants have been downgraded from a division (Magnoliophyta) to a subclass (Magnoliidae), and the superorder has become the rank that distinguishes the major groups of flowering plants.[8] The traditional classification of primates (class Mammalia—subclass Theria—infraclass Eutheria—order Primates) has been modified by new classifications such as McKenna and Bell (class Mammalia—subclass Theriformes—infraclass Holotheria) with Theria and Eutheria assigned lower ranks between infraclass and the order Primates. See mammal classification for a discussion. These differences arise because there are only a small number of ranks available and a large number of branching points in the fossil record.

- Within species further units may be recognised. Animals may be classified into subspecies (for example, Homo sapiens sapiens, modern humans) or morphs (for example Corvus corax varius morpha leucophaeus, the Pied Raven). Plants may be classified into subspecies (for example, Pisum sativum subsp. sativum, the garden pea) or varieties (for example, Pisum sativum var. macrocarpon, snow pea), with cultivated plants getting a cultivar name (for example, Pisum sativum var. macrocarpon 'Snowbird'). Bacteria may be classified by strains (for example Escherichia coli O157:H7, a strain that can cause food poisoning).

- Mnemonics are available at mnemonic-device.eu and thefreedictionary.com.

Terminations of names

Taxa above the genus level are often given names based on the type genus, with a standard termination. The terminations used in forming these names depend on the kingdom (and sometimes the phylum and class) as set out in the table below.

Pronunciations given are the most Anglicized. More Latinate pronunciations are also common, particularly /ɑː/ rather than /eɪ/ for stressed a.

| Rank | Bacteria[9] | Plants | Algae | Fungi | Animals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division/Phylum | -phyta /ˈfaɪtə/ | -phycota /ˈfaɪkoʊtə/ | -mycota /maɪˈkoʊtə/ | ||

| Subdivision/Subphylum | -phytina /fɪˈtaɪnə/ | -phycotina /fɪkoʊˈtaɪnə/ | -mycotina /maɪkoʊˈtaɪnə/ | ||

| Class | -ia /iə/ | -opsida /ˈɒpsɪdə/ | -phyceae /ˈfaɪʃiː/ | -mycetes /maɪˈsiːtiːz/ | |

| Subclass | -idae /ɪdiː/ | -phycidae /ˈfɪsɪdiː/ | -mycetidae /maɪˈsɛtɪdiː/ | ||

| Superorder | -anae /ˈeɪniː/ | ||||

| Order | -ales /ˈeɪliːz/ | ||||

| Suborder | -ineae /ˈɪnɪ.iː/ | ||||

| Infraorder | -aria /ˈɛəriə/ | ||||

| Superfamily | -acea /ˈeɪʃə/ | -oidea /ˈɔɪdiə/ | |||

| Epifamily | -oidae /ˈɔɪdiː/ | ||||

| Family | -aceae /ˈeɪʃiː/ | -idae /ɪdiː/ | |||

| Subfamily | -oideae /ˈɔɪdɪiː/ | -inae /ˈaɪniː/ | |||

| Infrafamily | -odd /ɒd/[10] | ||||

| Tribe | -eae /ɪiː/ | -ini /ˈaɪnaɪ/ | |||

| Subtribe | -inae /ˈaɪniː/ | -ina /ˈaɪnə/ | |||

| Infratribe | -ad /æd/ or -iti /ˈaɪti/ | ||||

- Table notes

- In botany and mycology names at the rank of family and below are based on the name of a genus, sometimes called the type genus of that taxon, with a standard ending. For example, the rose family Rosaceae is named after the genus Rosa, with the standard ending "-aceae" for a family. Names above the rank of family are also formed from a generic name, or are descriptive (like Gymnospermae or Fungi).

- For animals, there are standard suffixes for taxa only up to the rank of superfamily.[11]

- Forming a name based on a generic name may be not straightforward. For example, the Latin "homo" has the genitive "hominis", thus the genus "Homo" (human) is in the Hominidae, not "Homidae".

- The ranks of epifamily, infrafamily and infratribe (in animals) are used where the complexities of phyletic branching require finer-than-usual distinctions. Although they fall below the rank of superfamily, they are not regulated under the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature and hence do not have formal standard endings. The suffixes listed here are regular, but informal.[12]

All ranks

There is an indeterminate number of ranks, as a taxonomist may invent a new rank at will, at any time, if they feel this is necessary. In doing so, there are some restrictions, which will vary with the nomenclature code which applies.

The following is an artificial synthesis, solely for purposes of demonstration of relative rank (but see notes), from most general to most specific:[13]

- Domain or Empire

- Hyperkingdom

- Superkingdom

- Kingdom

- Subkingdom

- Infrakingdom

- Parvkingdom

- Infrakingdom

- Subkingdom

- Kingdom

- Superkingdom

- Superphylum (or Superdivision in botany)

- Phylum (or Division in botany)

- Subphylum (or Subdivision in botany)

- Infraphylum (or Infradivision in botany)

- Subphylum (or Subdivision in botany)

- Phylum (or Division in botany)

- Superclass

- Superdivision (zoology)[14]

- Superlegion (zoology)

- Legion (zoology)

- Sublegion (zoology)

- Infralegion (zoology)

- Sublegion (zoology)

- Legion (zoology)

- Supercohort (zoology)[15]

- Gigaorder (zoology)[16]

- Magnorder or Megaorder (zoology)[16]

- Grandorder or Capaxorder (zoology)[16]

- Mirorder or Hyperorder (zoology)[16]

- Grandorder or Capaxorder (zoology)[16]

- Magnorder or Megaorder (zoology)[16]

- Section (zoology)

- Subsection (zoology)

- Gigafamily (zoology)

- Supertribe

- Genus

- Subgenus

- Section (botany)

- Subsection (botany)

- Series (botany)

- Subseries (botany)

- Series (botany)

- Subsection (botany)

- Section (botany)

- Subgenus

- Superspecies or Species-group

- Species

- Subspecies (or Forma Specialis for fungi, or Variety for bacteria[17])

- Variety (botany) or Form/Morph (zoology)

- Subvariety (botany)

- Form (botany)

- Subform (botany)

- Form (botany)

- Subvariety (botany)

- Variety (botany) or Form/Morph (zoology)

- Subspecies (or Forma Specialis for fungi, or Variety for bacteria[17])

- Species

Significance and problems

Ranks are assigned based on subjective dissimilarity, and do not fully reflect the gradational nature of variation within nature. In most cases, higher taxonomic groupings arise further back in time: not because the rate of diversification was higher in the past, but because each subsequent diversification event results in an increase of diversity and thus increases the taxonomic rank assigned by present-day taxonomists.[18] Furthermore, some groups have many described species not because they are more diverse than other species, but because they are more easily sampled and studied than other group.

Of these many ranks, the most basic is species. However, this is not to say that a taxon at any other rank may not be sharply defined, or that any species is guaranteed to be sharply defined. It varies from case to case. Ideally, a taxon is intended to represent a clade, that is, the phylogeny of the organisms under discussion, but this is not a requirement.

Classification, in which all taxa have formal ranks, cannot adequately reflect knowledge about phylogeny; at the same time, if taxon names are dependent on ranks, rank-free taxa can't be supplied with names. This problem is dissolved in cladoendesis, where the specially elaborated rank-free nomenclatures are used.[19][20]

There are no rules for how many species should make a genus, a family, or any other higher taxon (that is, a taxon in a category above the species level).[21][22] It should be a natural group (that is, non-artificial, non-polyphyletic), as judged by a biologist, using all the information available to them. Equally ranked higher taxa in different phyla are not necessarily equivalent (e.g., it is incorrect to assume that families of insects are in some way evolutionarily comparable to families of mollusks).[22] For animals, at least the phylum rank is usually associated with a certain body plan, which is also, however, an arbitrary criterion.

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.123rf.com /clipart-vector/vulpes_vulpes.html

- ↑ International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants, Melbourne Code, 2012, articles 2 and 3

- ↑ International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (1999), International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. Fourth Edition, International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature

- ↑ Moore R.T. (1974). "Proposal for the recognition of super ranks" (PDF). Taxon. 23 (4): 650–652.

- ↑ Luketa S. (2012). "New views on the megaclassification of life" (PDF). Protistology. 7 (4): 218–237.

- ↑ International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants, Melbourne Code, 2012, articles 3 and 4

- ↑ Stearn, W.T. 1992. Botanical Latin: History, grammar, syntax, terminology and vocabulary, Fourth edition. David and Charles.

- ↑ Chase, M.W.; Reveal, J.L. (2009), "A phylogenetic classification of the land plants to accompany APG III", Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 161 (2): 122–127, doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.01002.x

- ↑ Bacteriologocal Code (1990 Revision)

- ↑ For example, the chelonian infrafamilies Chelodd (Gaffney & Meylan 1988: 169) and Baenodd (ibid., 176).

- ↑ ICZN article 29.2

- ↑ As supplied by Gaffney & Meylan (1988).

- ↑ For the general usage and coordination of zoological ranks between the phylum and family levels, including many intercalary ranks, see Carroll (1988). For additional intercalary ranks in zoology, see especially Gaffney & Meylan (1988); McKenna & Bell (1997); Milner (1988); Novacek (1986, cit. in Carroll 1988: 499, 629); and Paul Sereno's 1986 classification of ornithischian dinosaurs as reported in Lambert (1990: 149, 159). For botanical ranks, including many intercalary ranks, see Willis & McElwain (2002).

- 1 2 3 4 These are movable ranks, most often inserted between the class and the legion or cohort. Nevertheless, their positioning in the zoological hierarchy may be subject to wide variation. For examples, see the Benton classification of vertebrates (2005).

- 1 2 3 4 In zoological classification, the cohort and its associated group of ranks are inserted between the class group and the ordinal group. The cohort has also been used between infraorder and family in saurischian dinosaurs (Benton 2005). In botanical classification, the cohort group has sometimes been inserted between the division (phylum) group and the class group: see Willis & McElwain (2002: 100–101), or has sometimes been used at the rank of order, and is now considered to be an obsolete name for order: See International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants, Melbourne Code 2012, Article 17.2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 The supra-ordinal sequence gigaorder-megaorder-capaxorder-hyperorder (and the microorder, in roughly the position most often assigned to the parvorder) has been employed in turtles at least (Gaffney & Meylan 1988), while the parallel sequence magnorder-grandorder-mirorder figures in recently influential classifications of mammals. It is unclear from the sources how these two sequences are to be coordinated (or interwoven) within a unitary zoological hierarchy of ranks. Previously, Novacek (1986) and McKenna-Bell (1997) had inserted mirorders and grandorders between the order and superorder, but Benton (2005) now positions both of these ranks above the superorder.

- ↑ Additionally, the terms biovar, morphovar and serovar designate bacterial strains (genetic variants) that are physiologically or biochemically distinctive. These are not taxonomic ranks, but are groupings of various sorts which may define a bacterial subspecies.

- ↑ Gingerich, P. D. (1987). "Evolution and the fossil record: patterns, rates, and processes". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 65 (5): 1053–1060. doi:10.1139/z87-169.

- ↑ Kluge N.J. 1999. A system of alternative nomenclatures of supra-species taxa. Linnaean and post-Linnaean principles of systematics. // Entomological Review 79(2): 133-147

- ↑ Kluge N.J. 2010. Circumscriptional names of higher taxa in Hexapoda. // Bionomina 1: 15–55

- ↑ Stuessy, T.F. (2009). Plant Taxonomy: The Systematic Evaluation of Comparative Data. 2nd ed. Columbia University Press, p. 175.

- 1 2 Brusca, R.C. & Brusca, G.J. (2003). Invertebrates. 2nd ed. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates, pp. 26–27.

Bibliography

- Benton, Michael J. 2005. Vertebrate Palaeontology, 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-632-05637-1. ISBN 978-0-632-05637-8

- Brummitt, R.K., and C.E. Powell. 1992. Authors of Plant Names. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. ISBN 0-947643-44-3

- Carroll, Robert L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. New York: W.H. Freeman & Co. ISBN 0-7167-1822-7

- Gaffney, Eugene S., and Peter A. Meylan. 1988. "A phylogeny of turtles". In M.J. Benton (ed.), The Phylogeny and Classification of the Tetrapods, Volume 1: Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds, 157–219. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Haris Abba Kabara. Karmos hand book for botanical names.

- Lambert, David. 1990. Dinosaur Data Book. Oxford: Facts On File & British Museum (Natural History). ISBN 0-8160-2431-6

- McKenna, Malcolm C., and Susan K. Bell (editors). 1997. Classification of Mammals Above the Species Level. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11013-8

- Milner, Andrew. 1988. "The relationships and origin of living amphibians". In M.J. Benton (ed.), The Phylogeny and Classification of the Tetrapods, Volume 1: Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds, 59–102. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Novacek, Michael J. 1986. "The skull of leptictid insectivorans and the higher-level classification of eutherian mammals". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 183: 1–112.

- Sereno, Paul C. 1986. "Phylogeny of the bird-hipped dinosaurs (Order Ornithischia)". National Geographic Research 2: 234–56.

- Willis, K.J., and J.C. McElwain. 2002. The Evolution of Plants. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850065-3