Female infertility

| Female infertility | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | urology |

| ICD-10 | N97.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 628 |

| DiseasesDB | 4786 |

| MedlinePlus | 001191 |

| eMedicine | med/3535 |

| Patient UK | Female infertility |

| MeSH | D007247 |

Female infertility refers to infertility in female humans. It affects an estimated 48 million women[1] with the highest prevalence of infertility affecting people in South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa/Middle East, and Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia.[1] Infertility is caused by many sources, including nutrition, diseases, and other malformations of the uterus. Infertility affects women from around the world, and the cultural and social stigma surrounding it varies.

Definition

There is no unanimous definition of female infertility, because the definition depends on social and physical characteristics which may vary by culture and situation. NICE guidelines state that: "A woman of reproductive age who has not conceived after 1 year of unprotected vaginal sexual intercourse, in the absence of any known cause of infertility, should be offered further clinical assessment and investigation along with her partner."[2] It is recommended that a consultation with a fertility specialist should be made earlier if the woman is aged 36 years or over, or there is a known clinical cause of infertility or a history of predisposing factors for infertility.[2] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), infertility can be described as the inability to become pregnant, maintain a pregnancy, or carry a pregnancy to live birth.[3] A clinical definition of infertility by the WHO and ICMART is “a disease of the reproductive system defined by the failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse.” [4] Infertility can further be broken down into primary and secondary infertility. Primary infertility refers to the inability to give birth either because of not being able to become pregnant, or carry a child to live birth, which may include miscarriage or a stillborn child. [5][6] Secondary infertility refers to the inability to conceive or give birth when there was a previous pregnancy or live birth.[6][5]

Prevalence

Female infertility varies widely by geographic location around the world. In 2010, there was an estimated 48.5 million infertile couples worldwide, and from 1990 to 2010 there was little change in levels of infertility in most of the world.[1] In 2010, the countries with the lowest rates of female infertility included the South American countries of Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia, as well as in Poland, Kenya, and Republic of Korea.[1] The highest rate regions included Eastern Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, Oceania, and Sub-Saharan Africa.[1] The prevalence of primary infertility has increased since 1990, but secondary infertility has decreased overall. Rates decreased (although not prevalence) of female infertility in high-income, Central/Eastern Europe, and Central Asia regions.[1]

Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa has had decreasing levels of primary infertility from 1990 to 2010. Within the Sub-Saharan region, rates were lowest in Kenya, Zimbabwe, and Rwanda, while the highest rates were in Guinea, Mozambique, Angola, Gabon, and Cameroon along with Northern Africa near the Middle East.[1] According to a 2004 DHS report, rates in Africa were highest in Middle and Sub-Saharan Africa, with East Africa’s rates close behind.[6]

Asia

In Asia, the highest rates of combined secondary and primary infertility was in the South Central region, and then in the Southeast region, with the lowest rates in the Western areas.[6]

Latin America and Caribbean

The prevalence of female infertility in the Latin America/Caribbean region is typically lower than the global prevalence. However, the greatest rates occurred in Jamaica, Suriname, Haiti, and Trinidad and Tobago. Central and Western Latin America has some of the lowest rates of prevalence.[1] The highest regions in Latin America and the Caribbean was in the Caribbean Islands and in less developed countries.[6]

Causes and factors

Causes or factors of female infertility can basically be classified regarding whether they are acquired or genetic, or strictly by location.

Although factors of female infertility can be classified as either acquired or genetic, female infertility is usually more or less a combination of nature and nurture. Also, the presence of any single risk factor of female infertility (such as smoking, mentioned further below) does not necessarily cause infertility, and even if a woman is definitely infertile, the infertility cannot definitely be blamed on any single risk factor even if the risk factor is (or has been) present.

Acquired

According to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), Age, Smoking, Sexually Transmitted Infections, and Being Overweight or Underweight can all affect fertility.[7]

In broad sense, acquired factors practically include any factor that is not based on a genetic mutation, including any intrauterine exposure to toxins during fetal development, which may present as infertility many years later as an adult.

Age

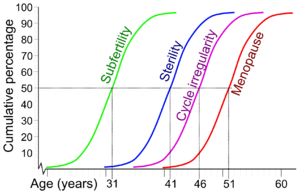

A woman's fertility is affected by her age. The average age of a girl's first period (menarche) is 12-13 (12.5 years in the United States,[9] 12.72 in Canada,[10] 12.9 in the UK[11]), but, in postmenarchal girls, about 80% of the cycles are anovulatory in the first year after menarche, 50% in the third and 10% in the sixth year.[12] A woman's fertility peaks in the early and mid 20s, after which it starts to decline, with this decline being accelerated after age 35. However, the exact estimates of the chances of a woman to conceive after a certain age are not clear, with research giving differing results. The chances of a couple to successfully conceive at an advanced age depend on many factors, including the general health of a woman and the fertility of the male partner.

Tobacco smoking

Tobacco smoking is harmful to the ovaries, and the degree of damage is dependent upon the amount and length of time a woman smokes or is exposed to a smoke-filled environment. Nicotine and other harmful chemicals in cigarettes interfere with the body’s ability to create estrogen, a hormone that regulates folliculogenesis and ovulation. Also, cigarette smoking interferes with folliculogenesis, embryo transport, endometrial receptivity, endometrial angiogenesis, uterine blood flow and the uterine myometrium.[13] Some damage is irreversible, but stopping smoking can prevent further damage.[14][15] Smokers are 60% more likely to be infertile than non-smokers.[16] Smoking reduces the chances of IVF producing a live birth by 34% and increases the risk of an IVF pregnancy miscarrying by 30%.[16] Also, female smokers have an earlier onset of menopause by approximately 1–4 years.[17]

Sexually transmitted infections

Sexually transmitted infections are a leading cause of infertility. They often display few, if any visible symptoms, with the risk of failing to seek proper treatment in time to prevent decreased fertility.[14]

Body weight and eating disorders

Twelve percent of all infertility cases are a result of a woman either being underweight or overweight. Fat cells produce estrogen,[18] in addition to the primary sex organs. Too much body fat causes production of too much estrogen and the body begins to react as if it is on birth control, limiting the odds of getting pregnant.[14] Too little body fat causes insufficient production of estrogen and disruption of the menstrual cycle.[14] Both under and overweight women have irregular cycles in which ovulation does not occur or is inadequate.[14] Proper nutrition in early life is also a major factor for later fertility.[19]

A study in the US indicated that approximately 20% of infertile women had a past or current eating disorder, which is five times higher than the general lifetime prevalence rate.[20]

A review from 2010 concluded that overweight and obese subfertile women have a reduced probability of successful fertility treatment and their pregnancies are associated with more complications and higher costs.[21] In hypothetical groups of 1000 women undergoing fertility care, the study counted approximately 800 live births for normal weight and 690 live births for overweight and obese anovulatory women. For ovulatory women, the study counted approximately 700 live births for normal weight, 550 live births for overweight and 530 live births for obese women. The increase in cost per live birth in anovulatory overweight and obese women were, respectively, 54 and 100% higher than their normal weight counterparts, for ovulatory women they were 44 and 70% higher, respectively.[22]

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy poses a high risk of infertility. Chemotherapies with high risk of infertility include procarbazine and other alkylating drugs such as cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, busulfan, melphalan, chlorambucil and chlormethine.[23] Drugs with medium risk include doxorubicin and platinum analogs such as cisplatin and carboplatin.[23] On the other hand, therapies with low risk of gonadotoxicity include plant derivatives such as vincristine and vinblastine, antibiotics such as bleomycin and dactinomycin and antimetabolites such as methotrexate, mercaptopurine and 5-fluorouracil.[23]

Female infertility by chemotherapy appears to be secondary to premature ovarian failure by loss of primordial follicles.[24] This loss is not necessarily a direct effect of the chemotherapeutic agents, but could be due to an increased rate of growth initiation to replace damaged developing follicles.[24] Antral follicle count decreases after three series of chemotherapy, whereas follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) reaches menopausal levels after four series.[25] Other hormonal changes in chemotherapy include decrease in inhibin B and anti-Müllerian hormone levels.[25]

Women may choose between several methods of fertility preservation prior to chemotherapy, including cryopreservation of ovarian tissue, oocytes or embryos.[26]

Other acquired factors

- Adhesions secondary to surgery in the peritoneal cavity is the leading cause of acquired infertility.[27] A meta-analysis in 2012 came to the conclusion that there is only little evidence for the surgical principle that using less invasive techniques, introducing less foreign bodies or causing less ischemia reduces the extent and severity of adhesions.[27]

- Diabetes mellitus. A review of type 1 diabetes came to the result that, despite modern treatment, women with diabetes are at increased risk of female infertility, such as reflected by delayed puberty and menarche, menstrual irregularities (especially oligomenorrhoea), mild hyperandrogenism, polycystic ovarian syndrome, fewer live born children and possibly earlier menopause.[28] Animal models indicate that abnormalities on the molecular level caused by diabetes include defective leptin, insulin and kisspeptin signalling.[28]

- Coeliac disease. Non-gastrointestinal symptoms of coeliac disease may include disorders of fertility, such as delayed menarche, amenorrea, infertility or early menopause; and pregnancy complications, such as intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), small for gestational age (SGA) babies, recurrent abortions, preterm deliveries or low birth weight (LBW) babies. Nevertheless, gluten-free diet reduces the risk. Some authors suggest that physicians should investigate the presence of undiagnosed coeliac disease in women with unexplained infertility, recurrent miscarriage or IUGR.[29][30]

- Significant liver or kidney disease

- Thrombophilia[31][32]

- Cannabis smoking, such as of marijuana causes disturbances in the endocannabinoid system, potentially causing infertility[33]

- Radiation, such as in radiation therapy. The radiation dose to the ovaries that generally causes permanent female infertility is 20.3 Gy at birth, 18.4 Gy at 10 years, 16.5 Gy at 20 years and 14.3 Gy at 30 years.[34] After total body irradiation, recovery of gonadal function occurs in 10−14% of cases, and the number of pregnancies observed after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation involving such as procedure is lower than 2%.[35][36]

Genetic factors

There are many genes wherein mutation causes female infertility, as shown in table below. Also, there are additional conditions involving female infertility which are believed to be genetic but where no single gene has been found to be responsible, notably Mayer-Rokitansky-Küstner-Hauser Syndrome (MRKH).[37] Finally, an unknown number of genetic mutations cause a state of subfertility, which in addition to other factors such as environmental ones may manifest as frank infertility.

Chromosomal abnormalities causing female infertility include Turner syndrome. Oocyte donation is an alternative for patients with Turner syndrome.[38]

Some of these gene or chromosome abnormalities cause intersexed conditions, such as androgen insensitivity syndrome.

| Gene | Encoded protein | Effect of deficiency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMP15 | Bone morphogenetic protein 15 | Hypergonadotrophic ovarian failure (POF4) | |

| BMPR1B | Bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1B | Ovarian dysfunction, hypergonadotrophic hypogonadism and acromesomelic chondrodysplasia | |

| CBX2; M33 | Chromobox protein homolog 2 ; Drosophila polycomb class |

Autosomal 46,XY, male-to-female sex reversal (phenotypically perfect females) | |

| CHD7 | Chromodomain-helicase-DNA-binding protein 7 | CHARGE syndrome and Kallmann syndrome (KAL5) | |

| DIAPH2 | Diaphanous homolog 2 | Hypergonadotrophic, premature ovarian failure (POF2A) | |

| FGF8 | Fibroblast growth factor 8 | Normosmic hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism and Kallmann syndrome (KAL6) | |

| FGFR1 | Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 | Kallmann syndrome (KAL2) | |

| HFM1 | Primary ovarian failure[40] | ||

| FSHR | FSH receptor | Hypergonadotrophic hypogonadism and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome | |

| FSHB | Follitropin subunit beta | Deficiency of follicle-stimulating hormone, primary amenorrhoea and infertility | |

| FOXL2 | Forkhead box L2 | Isolated premature ovarian failure (POF3) associated with BPES type I; FOXL2

402C --> G mutations associated with human granulosa cell tumours | |

| FMR1 | Fragile X mental retardation | Premature ovarian failure (POF1) associated with premutations | |

| GNRH1 | Gonadotropin releasing hormone | Normosmic hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism | |

| GNRHR | GnRH receptor | Hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism | |

| KAL1 | Kallmann syndrome | Hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism and insomnia, X-linked Kallmann syndrome (KAL1) | |

| KISS1R ; GPR54 | KISS1 receptor | Hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism | |

| LHB | Luteinizing hormone beta polypeptide | Hypogonadism and pseudohermaphroditism | |

| LHCGR | LH/choriogonadotrophin receptor | Hypergonadotrophic hypogonadism (luteinizing hormone resistance) | |

| DAX1 | Dosage-sensitive sex reversal, adrenal hypoplasia critical region, on chromosome X, gene 1 | X-linked congenital adrenal hypoplasia with hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism; dosage-sensitive male-to-female sex reversal | |

| NR5A1; SF1 | Steroidogenic factor 1 | 46,XY male-to-female sex reversal and streak gonads and congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia; 46,XX gonadal dysgenesis and 46,XX primary ovarian insufficiency | |

| POF1B | Premature ovarian failure 1B | Hypergonadotrophic, primary amenorrhea (POF2B) | |

| PROK2 | Prokineticin | Normosmic hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism and Kallmann syndrome (KAL4) | |

| PROKR2 | Prokineticin receptor 2 | Kallmann syndrome (KAL3) | |

| RSPO1 | R-spondin family, member 1 | 46,XX, female-to-male sex reversal (individuals contain testes) | |

| SRY | Sex-determining region Y | Mutations lead to 46,XY females; translocations lead to 46,XX males | |

| SOX9 | SRY-related HMB-box gene 9 | Autosomal 46,XY male-to-female sex reversal (campomelic dysplasia) | |

| STAG3 | Stromal antigen 3 | Premature ovarian failure[41] | |

| TAC3 | Tachykinin 3 | Normosmic hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism | |

| TACR3 | Tachykinin receptor 3 | Normosmic hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism | |

| ZP1 | zona pellucida glycoprotein 1 | Dysfunctional zona pellucida formation[42] |

By location

Hypothalamic-pituitary factors

Ovarian factors

- Chemotherapy (as detailed previously) with certain agents have a high risk of toxicity on the ovaries.

- Many genetic defects (as also detailed previously) also disturb ovarian function.

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (also see infertility in polycystic ovary syndrome)

- Anovulation. Female infertility caused by anovulation is called "anovulatory infertility", as opposed to "ovulatory infertility" in which ovulation is present.[44]

- Diminished ovarian reserve, also see Poor Ovarian Reserve

- Premature menopause

- Menopause

- Luteal dysfunction[45]

- Gonadal dysgenesis (Turner syndrome)

- Ovarian cancer

Tubal (ectopic)/peritoneal factors

- Endometriosis (also see endometriosis and infertility)

- Pelvic adhesions

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID, usually due to chlamydia)[46]

- Tubal occlusion[47]

- Tubal dysfunction

- Previous ectopic pregnancy. A randomized study in 2013 came to the result that the rates of intrauterine pregnancy 2 years after treatment of ectopic pregnancy are approximately 64% with radical surgery, 67% with medication, and 70% with conservative surgery.[48] In comparison, the cumulative pregnancy rate of women under 40 years of age in the general population over 2 years is over 90%.[2]

Uterine factors

- Uterine malformations[49]

- Uterine fibroids

- Asherman's Syndrome[50]

- Implantation failure without any known primary cause. It results in negative pregnancy test despite having performed e.g. embryo transfer.

Previously, a bicornuate uterus was thought to be associated with infertility,[51] but recent studies have not confirmed such an association.[52]

Cervical factors

- Cervical stenosis[53]

- Antisperm antibodies[54]

- Non-receptive cervical mucus[55]

Vaginal factors

- Vaginismus

- Vaginal obstruction

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of infertility begins with a medical history and physical exam. The healthcare provider may order tests, including the following:

- Lab tests

- hormone testing, to measure levels of female hormones at certain times during a menstrual cycle

- day 2 or 3 measure of FSH and estrogen, to assess ovarian reserve

- measurements of thyroid function[56] (a thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level of between 1 and 2 is considered optimal for conception)

- measurement of progesterone in the second half of the cycle to help confirm ovulation

- Anti-Müllerian hormone to estimate ovarian reserve.[57]

- Examination and imaging

- an endometrial biopsy, to verify ovulation and inspect the lining of the uterus

- laparoscopy, which allows the provider to inspect the pelvic organs

- fertiloscopy, a relatively new surgical technique used for early diagnosis (and immediate treatment)

- Pap smear, to check for signs of infection

- pelvic exam, to look for abnormalities or infection

- a postcoital test, which is done soon after intercourse to check for problems with sperm surviving in cervical mucous (not commonly used now because of test unreliability)

- Hysterosalpingography or sonosalpingography, to check for tube patency

- Sonohysterography to check for uterine abnormalities.

There are genetic testing techniques under development to detect any mutation in genes associated with female infertility.[39]

Initial diagnosis and treatment of infertility is usually made by obstetrician/gynecologists or women's health nurse practitioners. If initial treatments are unsuccessful, referral is usually made to physicians who are fellowship trained as reproductive endocrinologists. Reproductive endocrinologists are usually obstetrician/gynecologists with advanced training in reproductive endocrinology and infertility (in North America). These physicians treat reproductive disorders affecting not only women but also men, children, and teens.

Usually reproductive endocrinology & infertility medical practices do not see women for general maternity care. The practice is primarily focused on helping their women to conceive and to correct any issues related to recurring pregnancy loss.

Prevention

Acquired female infertility may be prevented through identified interventions:

- Maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Excessive exercise, consumption of caffeine and alcohol, and smoking have all been associated with decreased fertility. Eating a well-balanced, nutritious diet, with plenty of fresh fruits and vegetables, and maintaining a normal weight, on the other hand, have been associated with better fertility prospects.

- Treating or preventing existing diseases. Identifying and controlling chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypothyroidism increases fertility prospects. Lifelong practice of safer sex reduces the likelihood that sexually transmitted diseases will impair fertility; obtaining prompt treatment for sexually transmitted diseases reduces the likelihood that such infections will do significant damage. Regular physical examinations (including pap smears) help detect early signs of infections or abnormalities.

- Not delaying parenthood. Fertility does not ultimately cease before menopause, but it starts declining after age 27 and drops at a somewhat greater rate after age 35.[58] Women whose biological mothers had unusual or abnormal issues related to conceiving may be at particular risk for some conditions, such as premature menopause, that can be mitigated by not delaying parenthood.

- Egg freezing. A woman can freeze her eggs preserve her fertility. By using egg freezing while in the peak reproductive years, a woman's oocytes are cryogenically frozen and ready for her use later in life, reducing her chances of female infertility.[59]

Society and culture

Social stigma

Social stigma due to infertility is seen in many cultures throughout the world in varying forms. Often, when women cannot conceive, the blame is put on them, even when approximately 50% of infertility issues come from the man .[60] In addition, many societies only tend to value a woman if she is able to produce at least one child, and a marriage can be considered a failure when the couple cannot conceive.[60] The act of conceiving a child can be linked to the couple’s consummation of marriage, and reflect their social role in society.[61] This is seen in the "African infertility belt", where infertility is prevalent in Africa which includes countries spanning from Tanzania in the east to Gabon in the west.[60] In this region, infertility is highly stigmatized and can be considered a failure of the couple to their societies.[60][62] This is demonstrated in Uganda and Nigeria where there is a great pressure put on childbearing and its social implications.[61] This is also seen in some Muslim societies including Egypt [63] and Pakistan.[64]

Wealth is sometimes measured by the number of children a woman has, as well as inheritance of property.[61][64] Children can influence financial security in many ways. In Nigeria and Cameroon, land claims are decided by the number of children. Also, in some Sub-Saharan countries women may be denied inheritance if she did not bear any children [64] In some African and Asian countries a husband can deprive his infertile wife of food, shelter and other basic necessities like clothing.[64] In Cameroon, a woman may lose access to land from her husband and left on her own in old age.[61]

In many cases, a woman who cannot bear children is excluded from social and cultural events including traditional ceremonies. This stigmatization is seen in Mozambique and Nigeria where infertile women have been treated as outcasts to society.[61] This is a humiliating practice which devalues infertile women in society.[65][66] In the Macua tradition, pregnancy and birth are considered major life events for a woman, with the ceremonies of nthaa´ra and ntha´ara no mwana, which can only be attended by women who have been pregnant and have had a baby.[65]

The effect of infertility can lead to social shaming from internal and social norms surrounding pregnancy, which affects women around the world.[66] When pregnancy is considered such an important event in life, and considered a “socially unacceptable condition”, it can lead to a search for treatment in the form of traditional healers and expensive Western treatments.[63] The limited access to treatment in many areas can lead to extreme and sometimes illegal acts in order to produce a child.[61][63]

Marital role

Men in some countries may find another wife when their first cannot produce a child, hoping that by sleeping with more women he will be able to produce his own child.[61][63][64] This can be prevalent in some societies, including Cameroon,[61][64] Nigeria,[61] Mozambique,[65] Egypt,[63] Botswana,[67] and Bangladesh,[64] among many more where polygamy is more common and more socially acceptable.

In some cultures, including Botswana [67] and Nigeria,[61] women can select a woman with whom she allows her husband to sleep with in hopes of conceiving a child.[61] Women who are desperate for children may compromise with her husband to select a woman and accept duties of taking care of the children to feel accepted and useful in society.[67]

Women may also sleep with other men in hopes of becoming pregnant.[65] This can be done for many reasons including advice from a traditional healer, or finding if another man was "more compatible". In many cases, the husband was not aware of the extra sexual relations and would not be informed if a woman became pregnant by another man.[65] This is not as culturally acceptable however, and can contribute to the gendered suffering of women who have fewer options to become pregnant on their own as opposed to men.[63]

Men and women can also turn to divorce in attempt to find a new partner with whom to bear a child. Infertility in many cultures is a reason for divorce, and a way for a man or woman to increase his/her chances of producing an heir.[61][63][65][67] When a woman is divorced, she can lose her security that often comes with land, wealth, and a family.[67] This can ruin marriages and can lead to distrust in the marriage. The increase of sexual partners can potentially result with the spread of disease including HIV/AIDS, and can actually contribute to future generations of infertility.[67]

Domestic abuse

The emotional strain and stress that comes with infertility in the household can lead to the mistreatment and domestic abuse of a woman. The devaluation of a wife due to her inability to conceive can lead to domestic abuse and emotional trauma such as victim blaming. Women are sometimes or often blamed as the cause of a couples' infertility, which can lead to emotional abuse, anxiety, and shame.[61] In addition, blame for not being able to conceive is often put on the female, even if it is the man who is infertile.[60] Women who are not able to conceive can be starved, beaten, and may be neglected financially by her husband as if she had no child bearing use to him.[64] The physical abuse related to infertility may result from this and the emotional stress that comes with it. In some countries, the emotional and physical abuses that come with infertility can potentially lead to assault, murder, and suicide.[68]

Mental and psychological impact

Many infertile women tend to cope with immense stress and social stigma behind their condition, which can lead to considerable mental distress.[69] The long-term stress involved in attempting to conceive a child and the social pressures behind giving birth can lead to emotional distress that may manifest as mental disease.[70] Women who suffer from infertility might deal with psychological stressors such as denial, anger, grief, guilt, and depression.[71] There can be considerable social shaming that can lead to intense feelings of sadness and frustration that potentially contribute to depression and suicide.[67] The implications behind infertility bear huge consequences for the mental health of an infertile woman because of the social pressures and personal grief behind being unable to bear children.

See also

- Infertility

- Male infertility

- Meiosis

- Oncofertility

- Primary infertility

- Secondary infertility

- Fertility

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mascarenhas M.N.; Flaxman S.R.; Boerma T.; Vanderpoel S.; Stevens G.A. (2012). "National, Regional, and Global Trends in Infertility Prevalence Since 1990: A Systematic Analysis of 277 Health Surveys". PLOS Med. 9 (12): e1001356. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001356.

- 1 2 3 Fertility: assessment and treatment for people with fertility problems. NICE clinical guideline CG156 - Issued: February 2013

- ↑ World Health Organization 2013. "Health Topics: Infertility". Available http://www.who.int/topics/infertility/en/. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ↑ Zegers-Hochschild F.; Adamson G.D.; de Mouzon J.; Ishihara O.; Mansour R.; Nygren K.; Sullivan E.; van der Poel S. (2009). "The International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) Revised Glossary on ART Terminology, 2009". Human Reproduction. 24 (11): 2683–2687. doi:10.1093/humrep/dep343.

- 1 2 World Health Organization 2013."Sexual and reproductive health: Infertility definitions and terminology". Available http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/infertility/definitions/en/.Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rutstein, Shea O., and Iqbal H. Shah. "Infecundity, Infertility, and Childlessness in Developing Countries." DHS Comparative Reports No. 9 (2004): 1-57.

- ↑ http://www.fertilityfaq.org/_pdf/magazine1_v4.pdf

- ↑ te Velde, E. R. (2002). "The variability of female reproductive ageing". Human Reproduction Update. 8 (2): 141–154. ISSN 1355-4786. doi:10.1093/humupd/8.2.141.

- ↑ Anderson SE, Dallal GE, Must A (April 2003). "Relative weight and race influence average age at menarche: results from two nationally representative surveys of US girls studied 25 years apart". Pediatrics. 111 (4 Pt 1): 844–50. PMID 12671122. doi:10.1542/peds.111.4.844.

- ↑ Al-Sahab B, Ardern CI, Hamadeh MJ, Tamim H (2010). "Age at menarche in Canada: results from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children & Youth". BMC Public Health. 10: 736. PMC 3001737

. PMID 21110899. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-736.

. PMID 21110899. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-736. - ↑ http://vstudentworld.yolasite.com/resources/final_yr/gynae_obs/Hamilton%20Fairley%20Obstetrics%20and%20Gynaecology%20Lecture%20Notes%202%20Ed.pdf

- ↑ Apter D (February 1980). "Serum steroids and pituitary hormones in female puberty: a partly longitudinal study". Clinical Endocrinology. 12 (2): 107–20. PMID 6249519. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1980.tb02125.x.

- ↑ Dechanet C, Anahory T, Mathieu Daude JC, Quantin X, Reyftmann L, Hamamah S, Hedon B, Dechaud H (2011). "Effects of cigarette smoking on reproduction". Hum. Reprod. Update. 17 (1): 76–95. PMID 20685716. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq033.

- 1 2 3 4 5 FERTILITY FACT > Female Risks Archived September 22, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. By the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM). Retrieved on Jan 4, 2009

- ↑ http://dl.dropbox.com/u/8256710/ASRM%20Protect%20Your%20Fertility%20newsletter.pdf

- 1 2 Regulated fertility services: a commissioning aid - June 2009, from the Department of Health UK

- ↑ Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine (2008). "Smoking and Infertility". Fertil Steril. 90 (5 Suppl): S254–9. PMID 19007641. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.035.

- ↑ Nelson LR, Bulun SE (September 2001). "Estrogen production and action". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 45 (3 Suppl): S116–24. PMID 11511861. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.117432.

- ↑ Sloboda, D. M.; Hickey, M.; Hart, R. (2010). "Reproduction in females: the role of the early life environment". Human Reproduction Update. 17 (2): 210–227. PMID 20961922. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq048.

- ↑ Freizinger M, Franko DL, Dacey M, Okun B, Domar AD (November 2008). "The prevalence of eating disorders in infertile women". Fertil. Steril. 93 (1): 72–8. PMID 19006795. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.055.

- ↑ "Fertility of male and female and treatment". Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ↑ Koning AM, Kuchenbecker WK, Groen H, et al. (2010). "Economic consequences of overweight and obesity in infertility: a framework for evaluating the costs and outcomes of fertility care". Hum. Reprod. Update. 16 (3): 246–54. PMID 20056674. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmp053.

- 1 2 3 Brydøy M, Fosså SD, Dahl O, Bjøro T (2007). "Gonadal dysfunction and fertility problems in cancer survivors". Acta Oncol. 46 (4): 480–9. PMID 17497315. doi:10.1080/02841860601166958.

- 1 2 Morgan, S.; Anderson, R. A.; Gourley, C.; Wallace, W. H.; Spears, N. (2012). "How do chemotherapeutic agents damage the ovary?". Human Reproduction Update. 18 (5): 525–35. PMID 22647504. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms022.

- 1 2 Rosendahl, M.; Andersen, C.; La Cour Freiesleben, N.; Juul, A.; Løssl, K.; Andersen, A. (2010). "Dynamics and mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced ovarian follicular depletion in women of fertile age". Fertility and Sterility. 94 (1): 156–166. PMID 19342041. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.043.

- ↑ Gurgan T, Salman C, Demirol A (October 2008). "Pregnancy and assisted reproduction techniques in men and women after cancer treatment". Placenta. 29 (Suppl B): 152–9. PMID 18790328. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2008.07.007.

- 1 2 Ten Broek, R. P. G.; Kok- Krant, N.; Bakkum, E. A.; Bleichrodt, R. P.; Van Goor, H. (2012). "Different surgical techniques to reduce post-operative adhesion formation: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update. 19 (1): 12–25. PMID 22899657. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms032.

- 1 2 Codner, E.; Merino, P. M.; Tena-Sempere, M. (2012). "Female reproduction and type 1 diabetes: From mechanisms to clinical findings". Human Reproduction Update. 18 (5): 568–585. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms024.

- ↑ Tersigni C, Castellani R, de Waure C, Fattorossi A, De Spirito M, Gasbarrini A, Scambia G, Di Simone N (2014). "Celiac disease and reproductive disorders: meta-analysis of epidemiologic associations and potential pathogenic mechanisms". Hum Reprod Update (Meta-Analysis. Review). 20 (4): 582–93. PMID 24619876. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu007.

- ↑ Lasa, JS; Zubiaurre, I; Soifer, LO (2014). "Risk of infertility in patients with celiac disease: a meta-analysis of observational studies". Arq Gastroenterol (Meta-Analysis. Review). 51 (2): 144–50. PMID 25003268. doi:10.1590/S0004-28032014000200014.

- ↑ Middeldorp S (2007). "Pregnancy failure and heritable thrombophilia". Semin. Hematol. 44 (2): 93–7. PMID 17433901. doi:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2007.01.005.

- ↑ Qublan HS, Eid SS, Ababneh HA, et al. (2006). "Acquired and inherited thrombophilia: implication in recurrent IVF and embryo transfer failure". Hum. Reprod. 21 (10): 2694–8. PMID 16835215. doi:10.1093/humrep/del203.

- ↑ Karasu, T.; Marczylo, T. H.; MacCarrone, M.; Konje, J. C. (2011). "The role of sex steroid hormones, cytokines and the endocannabinoid system in female fertility". Human Reproduction Update. 17 (3): 347–361. PMID 21227997. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq058.

- ↑ Tichelli André; Rovó Alicia (2013). "Fertility Issues Following Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation". Expert Rev Hematol. 6 (4): 375–388. PMID 23991924. doi:10.1586/17474086.2013.816507.

In turn citing: Wallace WH, Thomson AB, Saran F, Kelsey TW (2005). "Predicting age of ovarian failure after radiation to a field that includes the ovaries". Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 62 (3): 738–744. - ↑ Tichelli André; Rovó Alicia (2013). "Fertility Issues Following Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation". Expert Rev Hematol. 6 (4): 375–388. PMID 23991924. doi:10.1586/17474086.2013.816507.

- ↑

In turn citing: Salooja N, Szydlo RM, Socie G, et al. "Pregnancy outcomes after peripheral blood or bone marrow transplantation: a retrospective survey". Lancet. 358 (9278): 271–276. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05482-4. - ↑ Sultan C, Biason-Lauber A, Philibert P (January 2009). "Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome: recent clinical and genetic findings". Gynecol Endocrinol. 25 (1): 8–11. PMID 19165657. doi:10.1080/09513590802288291.

- ↑ Bodri D, Vernaeve V, Figueras F, Vidal R, Guillén JJ, Coll O (March 2006). "Oocyte donation in patients with Turner's syndrome: a successful technique but with an accompanying high risk of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy". Hum Reprod. 2006 Mar;21(3). 21: 829–832. PMID 16311294. doi:10.1093/humrep/dei396.

- 1 2 Unless otherwise specified in boxes, then reference is: The Evian Annual Reproduction (EVAR) Workshop Group 2010; Fauser, B. C. J. M.; Diedrich, K.; Bouchard, P.; Domínguez, F.; Matzuk, M.; Franks, S.; Hamamah, S.; Simón, C.; Devroey, P.; Ezcurra, D.; Howles, C. M. (2011). "Contemporary genetic technologies and female reproduction". Human Reproduction Update. 17 (6): 829–847. PMC 3191938

. PMID 21896560. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr033.

. PMID 21896560. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr033. - ↑ Wang, Jian; Zhang, Wenxiang; Jiang, Hong; Wu, Bai-Lin (2014). "Mutations inHFM1in Recessive Primary Ovarian Insufficiency". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (10): 972–974. ISSN 0028-4793. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1310150.

- ↑ Caburet, Sandrine; Arboleda, Valerie A.; Llano, Elena; Overbeek, Paul A.; Barbero, Jose Luis; Oka, Kazuhiro; Harrison, Wilbur; Vaiman, Daniel; Ben-Neriah, Ziva; García-Tuñón, Ignacio; Fellous, Marc; Pendás, Alberto M.; Veitia, Reiner A.; Vilain, Eric (2014). "Mutant Cohesin in Premature Ovarian Failure". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (10): 943–949. ISSN 0028-4793. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1309635.

- ↑ Huang, Hua-Lin; Lv, Chao; Zhao, Ying-Chun; Li, Wen; He, Xue-Mei; Li, Ping; Sha, Ai-Guo; Tian, Xiao; Papasian, Christopher J.; Deng, Hong-Wen; Lu, Guang-Xiu; Xiao, Hong-Mei (2014). "Mutant ZP1 in Familial Infertility". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (13): 1220–1226. ISSN 0028-4793. PMC 4076492

. PMID 24670168. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1308851.

. PMID 24670168. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1308851. - ↑ Female Infertility

- ↑ Hull MG, Savage PE, Bromham DR (June 1982). "Anovulatory and ovulatory infertility: results with simplified management". Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 284 (6330): 1681–5. PMC 1498620

. PMID 6805656. doi:10.1136/bmj.284.6330.1681.

. PMID 6805656. doi:10.1136/bmj.284.6330.1681. - ↑ Luteal Phase Dysfunction at eMedicine

- ↑ Guven MA, Dilek U, Pata O, Dilek S, Ciragil P (2007). "Prevalence of Chlamydia trochomatis, Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis infections in the unexplained infertile women". Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 276 (3): 219–23. PMID 17160569. doi:10.1007/s00404-006-0279-z.

- ↑ García-Ulloa AC, Arrieta O (2005). "Tubal occlusion causing infertility due to an excessive inflammatory response in patients with predisposition for keloid formation". Med. Hypotheses. 65 (5): 908–14. PMID 16005574. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2005.03.031.

- ↑ Fernandez, H.; Capmas, P.; Lucot, J. P.; Resch, B.; Panel, P.; Bouyer, J. (2013). "Fertility after ectopic pregnancy: The DEMETER randomized trial". Human Reproduction. 28 (5): 1247–1253. PMID 23482340. doi:10.1093/humrep/det037.

- ↑ Raga F, Bauset C, Remohi J, Bonilla-Musoles F, Simón C, Pellicer A (1997). "Reproductive impact of congenital Müllerian anomalies". Hum. Reprod. 12 (10): 2277–81. PMID 9402295. doi:10.1093/humrep/12.10.2277.

- ↑ Magos A (2002). "Hysteroscopic treatment of Asherman's syndrome". Reprod. Biomed. Online. 4 (Suppl 3): 46–51. PMID 12470565. doi:10.1016/s1472-6483(12)60116-3.

- ↑ Shuiqing M, Xuming B, Jinghe L (2002). "Pregnancy and its outcome in women with malformed uterus". Chin. Med. Sci. J. 17 (4): 242–5. PMID 12901513.

- ↑ Proctor JA, Haney AF (2003). "Recurrent first trimester pregnancy loss is associated with uterine septum but not with bicornuate uterus". Fertil. Steril. 80 (5): 1212–5. PMID 14607577. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(03)01169-5.

- ↑ Tan Y, Bennett MJ (2007). "Urinary catheter stent placement for treatment of cervical stenosis". The Australian & New Zealand journal of obstetrics & gynaecology. 47 (5): 406–9. PMID 17877600. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2007.00766.x.

- ↑ Francavilla F, Santucci R, Barbonetti A, Francavilla S (2007). "Naturally-occurring antisperm antibodies in men: interference with fertility and clinical implications. An update". Front. Biosci. 12 (8–12): 2890–911. PMID 17485267. doi:10.2741/2280.

- ↑ Farhi J, Valentine A, Bahadur G, Shenfield F, Steele SJ, Jacobs HS (1995). "In-vitro cervical mucus-sperm penetration tests and outcome of infertility treatments in couples with repeatedly negative post-coital tests". Hum. Reprod. 10 (1): 85–90. PMID 7745077. doi:10.1093/humrep/10.1.85.

- ↑ Wartofsky L, Van Nostrand D, Burman KD (2006). "Overt and 'subclinical' hypothyroidism in women". Obstetrical & gynecological survey. 61 (8): 535–42. PMID 16842634. doi:10.1097/01.ogx.0000228778.95752.66.

- ↑ Broer, S. L.; Broekmans, F. J. M.; Laven, J. S. E.; Fauser, B. C. J. M. (2014). "Anti-Mullerian hormone: ovarian reserve testing and its potential clinical implications". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (5): 688–701. ISSN 1355-4786. PMID 24821925. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu020.

- ↑ Hall, Carl T. (April 30, 2002). "Study speeds up biological clocks / Fertility rates dip after women hit 27". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Information on Egg Freezing". Egg Freezing. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 WHO (2010). "Mother or nothing: the agony of infertility". Bulletin World Health Organization. 88: 881–882. doi:10.2471/BLT.10.011210.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Araoye, M. O. (2003). "Epidemiology of infertility: social problems of the infertile couples." West African journal of medicine (22;2): 190-196.

- ↑ Robert J. Leke, Jemimah A. Oduma, Susana Bassol-Mayagoitia, Angela Maria Bacha, and Kenneth M. Grigor. "Regional and Geographical Variations in Infertility: Effects of Environmental, Cultural, and Socioeconomic Factors" Environmental Health Perspectives Supplements (101) (Suppl. 2): 73-80 (1993).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Inhorn, M. C. (2003). "Global infertility and the globalization of new reproductive technologies: illustrations from Egypt." Social Science & Medicine (56): 1837 - 1851.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Dyer, S. J. (2012). "The economic impact of infertility on women in developing countries – a systematic review." FVV in ObGyn: 38-45.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gerrits, T. (1997). "Social and cultural aspects of infertility in Mozambique." Patient Education and Counseling (31): 39-48.

- 1 2 Whiteford, L. M. (1995). "STIGMA: THE HIDDEN BURDEN OF INFERTILITY." Sot. Sci. Med. (40;1): 27-36.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mogobe, D. K. (2005). "Denying and Preserving Self: Batswana Women's Experiences of Infertility." African Journal of Reproductive Health (9;2): 26-37.

- ↑ Omberlet, W. (2012). "Global access to infertility care in developing countries: a case of human rights, equity and social justice " FVV in ObGyn: 7-16.

- ↑ McQuillian, J., Greil, A.L., White, L., Jacob, M.C. (2003). "Frustrated Fertility: Infertility and Psychological Distress among Women." Journal of Marriage and Family (65;4): 1007-1018.

- ↑ Reproductive Health Outlook (2002). "Infertility: Overview and lessons learned."

- ↑ Matthews A. M.; Matthews R. (1986). "Beyond the Mechanics of Infertility: Perspectives on the Social Psychology of Infertility and Involuntary Childlessness". Family Relations. 35 (4): 479–487. doi:10.2307/584507.