Takotsubo cardiomyopathy

| Takotsubo cardiomyopathy | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Transient apical ballooning syndrome,[1] apical ballooning cardiomyopathy,[2] stress-induced cardiomyopathy, Gebrochenes-Herz-Syndrom, broken-heart syndrome |

| |

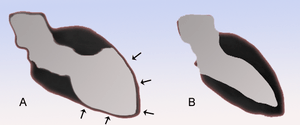

| Schematic representation of takotsubo cardiomyopathy (A) compared to a normal heart (B) | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, also known as stress cardiomyopathy, is a type of non-ischemic cardiomyopathy in which there is a sudden temporary weakening of the muscular portion of the heart.[3] This weakening may be triggered by emotional stress, such as the death of a loved one, a break-up, or constant anxiety. This leads to one of the common names, broken heart syndrome.[4] Stress cardiomyopathy is now a well-recognized cause of acute heart failure, lethal ventricular arrhythmias, and ventricular rupture.[5]

The name "Takotsubo syndrome" comes from the Japanese word for a kind of octopus trap (ja),[5] because the left ventricle takes on a shape resembling a fishing pot.

Signs and symptoms

The typical presentation of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is a sudden onset of chest pain associated with ECG changes mimicking a myocardial infarction of the anterior wall. During the course of evaluation of the patient, a bulging out of the left ventricular apex with a hypercontractile base of the left ventricle is often noted. It is the hallmark bulging out of the apex of the heart with preserved function of the base that earned the syndrome its name "tako tsubo", or octopus pot in Japan, where it was first described.[6]

Stress is the main factor in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, with more than 85% of cases set in motion by either a physically or emotionally stressful event that prefaces the start of symptoms.[7] Examples of emotional stressors include grief from the death of a loved one, fear of public speaking, arguing with a spouse, relationship disagreements, betrayal, and financial problems.[7] Acute asthma, surgery, chemotherapy, and stroke are examples of physical stressors.[7] In a few cases, the stress may be a happy event, such as a wedding, winning a jackpot, a sporting triumph, a reunion, or a birthday.[8][9]

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is more commonly seen in postmenopausal women.[10] Often there is a history of a recent severe (usually negative, sometimes happy) emotional or physical stress.[10]

Causes

The cause of takotsubo cardiomyopathy is not fully understood, but several mechanisms have been proposed.

- Wraparound LAD: The left anterior descending artery (LAD) supplies the anterior wall of the left ventricle in the majority of patients. If this artery also wraps around the apex of the heart, it may be responsible for blood supply to the apex and the inferior wall of the heart. Some researchers have noted a correlation between takotsubo and this type of LAD.[11] Other researchers have shown that this anatomical variant is not common enough to explain takotsubo cardiomyopathy.[12] This theory would also not explain documented variants where the midventricular walls or base of the heart does not contract (akinesis).

- Transient vasospasm: Some of the original researchers of takotsubo suggested that multiple simultaneous spasms of coronary arteries could cause enough loss of blood flow to cause transient stunning of the myocardium.[13] Other researchers have shown that vasospasm is much less common than initially thought.[14][15][16] It also has been noted that when there are vasospasms, even in multiple arteries, that they do not correlate with the areas of myocardium that are not contracting.[17]

- Microvascular dysfunction: The theory gaining the most traction is that there is dysfunction of the coronary arteries at the level where they are no longer visible by coronary angiography. This could include microvascular vasospasm, however, it may well also have some similarities to diseases such as diabetes mellitus. In such disease conditions the microvascular arteries fail to provide adequate oxygen to the myocardium.

- Mid-ventricular obstruction, apical stunning It also has been suggested that a mid-ventricular wall thickening with outflow obstruction is important in the pathophysiology.[18]

It is likely that there are multiple factors at play that could include some amount of vasospasm, failure of the microvasculature, and an abnormal response to catecholamines (such as epinephrine and norepinephrine, released in response to stress).[19] This heart dysfunction could be grouped within the psychosomatic disorders known as voodoo death.

Case series looking at large groups of patients report that some patients develop Takotsubo cardiomyopathy after an emotional stress, while others have a preceding clinical stressor (such as an asthma attack or sudden illness). Roughly one-third of patients have no preceding stressful event.[20] A recent large case series from Europe found that Takotsubo cardiomyopathy was slightly more frequent during the winter season. This may be related to two different possible/suspected pathophysiological causes: coronary spasms of microvessels, which are more prevalent in cold weather, and viral infections – such as Parvovirus B19 – which occur more frequently during the winter season.[1]

Diagnosis

Transient apical ballooning syndrome or Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is found in 1.7–2.2% of patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome.[1] While the original case studies reported on individuals in Japan, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy has been noted more recently in the United States and Western Europe. It is likely that the syndrome previously went undiagnosed before it was described in detail in the Japanese literature. Evaluation of individuals with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy typically includes a coronary angiogram, which will not reveal any significant blockages that would cause the left ventricular dysfunction. Provided that the individual survives their initial presentation, the left ventricular function improves within two months.

The diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy may be difficult upon presentation. The ECG findings often are confused with those found during an acute anterior wall myocardial infarction.[10][21] It classically mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, and is characterised by acute onset of transient ventricular apical wall motion abnormalities (ballooning) accompanied by chest pain, shortness of breath, ST-segment elevation, T-wave inversion or QT-interval prolongation on ECG. Cardiac enzymes are usually negative and are moderate at worst, and cardiac catheterization usually shows absence of significant coronary artery disease.[1]

The diagnosis is made by the pathognomonic wall motion abnormalities, in which the base of the left ventricle is contracting normally or is hyperkinetic while the remainder of the left ventricle is akinetic or dyskinetic. This is accompanied by the lack of significant coronary artery disease that would explain the wall motion abnormalities. Although apical ballooning has been described classically as the angiographic manifestation of takotsubo, it has been shown that left ventricular dysfunction in this syndrome includes not only the classic apical ballooning, but also different angiographic morphologies such as mid-ventricular ballooning and, rarely, local ballooning of other segments.[1][22][23][24][25]

The ballooning patterns were classified by Shimizu et al. as Takotsubo type for apical akinesia and basal hyperkinesia, reverse Takotsubo for basal akinesia and apical hyperkinesia, mid-ventricular type for mid-ventricular ballooning accompanied by basal and apical hyperkinesia, and localised type for any other segmental left ventricular ballooning with clinical characteristics of Takotsubo-like left ventricular dysfunction.[23]

Focal myocytolysis is reported as an origin of this cardiomyopathy. No microbiological agent has been associated so far with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Kloner et al. reported that a pathological change in the myocardium was not demonstrated in the stunned myocardium. Infiltration of small mononuclear cells has been documented in some cases; these pathological findings suggest that this cardiomyopathy is a kind of inflammatory heart disease, but not a coronary heart disease. There is also a report describing histologic myocardial damage without coronary heart disease.[26]

In short, the main criteria for the diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy are: the patient must have experienced a stressor before the symptoms began to arise; the patient’s ECG reading must show abnormalities from a normal heart; the patient must not show signs of coronary blockage or other common causes of heart troubles; the levels of cardiac enzymes in the heart must be elevated or irregular; and the patient must recover complete contraction and be functioning normally in a short amount of time.[27]

Left ventriculography during systole showing apical ballooning akinesis with basal hyperkinesis in a characteristic Takotsubo ventricle

Left ventriculography during systole showing apical ballooning akinesis with basal hyperkinesis in a characteristic Takotsubo ventricle Left ventriculogram during systole displaying the characteristic apical ballooning with apical motionlessness in a patient with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy

Left ventriculogram during systole displaying the characteristic apical ballooning with apical motionlessness in a patient with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (A) Echocardiogram showing dilatation of the left ventricle in the acute phase (B) Resolution of left ventricular function on repeat echocardiogram six days later

(A) Echocardiogram showing dilatation of the left ventricle in the acute phase (B) Resolution of left ventricular function on repeat echocardiogram six days later- ECG showing sinus tachycardia and non-specific ST and T wave changes from a person with confirmed takotsubo cardiomyopathy

- Echocardiogram showing the effects of the disease[28]

Treatment

The treatment of takotsubo cardiomyopathy is generally supportive in nature. Although patients with takotsubo heart disease may have low blood pressure, treatment with inotropes will usually exacerbate the disease. Since the disease is due to a high catecholamine state, patients should not be given inotropes. Treatment recommendations include intra-aortic balloon pump, fluids, and negative inotropes such as beta blockers or calcium channel blockers. In many individuals, left ventricular function normalizes within two months.[29][30] Aspirin and other heart drugs also appear to help in the treatment of this disease, even in extreme cases.[31][32] After the patient has been diagnosed, and myocardial infarction (heart attack) ruled out, the aspirin regimen may be discontinued, and treatment becomes that of supporting the patient.[33]

While medical treatments are important to address the acute symptoms of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, further treatment includes lifestyle changes.[34] It is important that the individual stay physically healthy while learning and maintaining methods to manage stress, and to cope with future difficult situations.

Prognosis

Despite the grave initial presentation in some of the patients, most of the patients survive the initial acute event, with a very low rate of in-hospital mortality or complications. Once a patient has recovered from the acute stage of the syndrome, they can expect a favorable outcome and the long-term prognosis is excellent.[1][6][22] Even when ventricular systolic function is heavily compromised at presentation, it typically improves within the first few days and normalises within the first few months.[1][14][15][16] Although infrequent, recurrence of the syndrome has been reported and seems to be associated with the nature of the trigger.[1][20]

Epidemiology

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is rare, affecting between 1.2% and 2.2% of people in Japan and 2% to 3% in western countries who suffer a myocardial infarction. It also affects far more women than men with 90% of cases being women, most postmenopausal. Scientists believe one reason is that estrogen causes the release of catecholamine and glucocorticoid in response to mental stress. It is not likely for the same recovered patient to experience the syndrome twice, although it has happened in rare cases.[35] The average ages at onset are between 58 and 75 years. Less than 3% of cases occurred in patients under age 50.[36]

History

Although the first scientific description of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy was not until the 1990s, Cebelin and Hirsch wrote about human stress cardiomyopathy in 1980. The two looked at homicidal assaults that had happened in Cuyahoga County, Ohio the past 30 years, specifically those with autopsies who had no internal injury, but had died of physical assault. They found that 11 of 15 had myofibrillar degeneration similar to animal stress studies. In the end, they concluded their data supported "the theory of catecholamine mediation of these myocardial changes in man and of the lethal potential of stress through its effect on the heart".[37]

The first studied case of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy was in Japan in 1991 by Sato et al. More cases of the syndrome appeared in Japan within the next decade, although western medicine had still not acknowledged it. The syndrome finally occurred in 1997 when Pavin et al. wrote about two cases of "reversible LV dysfunction precipitated by acute emotional stress." The western world had not heard of such a thing at the time, as it was incredibly rare and often misdiagnosed. The Japanese at last reported about the syndrome to the west in 2001 under the name "transient LV apical ballooning" though at this point the west had already heard of numerous cases. The syndrome reached international audiences through the media in 2005 when the New England Journal of Medicine wrote about the syndrome.[38]

Cultural references

A case of what is evidently takotsubo syndrome is a central motif of the end of the novel Blossoms in Autumn (Slovene: Cvetje v jeseni: 1917) by Slovene writer Ivan Tavčar and the film Blossoms in Autumn (1973) shot after it. A village girl named Meta suddenly dies after she had been asked by Janez, a lawyer from Ljubljana that she had spent summer with, to marry him. At her funeral, her father states that she was never very healthy, and that she had a heart defect. Her mother states: "She has died from happiness."[39][40]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Eshtehardi P, Koestner SC, Adorjan P, Windecker S, Meier B, Hess OM, Wahl A, Cook S (July 2009). "Transient apical ballooning syndrome--clinical characteristics, ballooning pattern, and long-term follow-up in a Swiss population". Int. J. Cardiol. 135 (3): 370–5. PMID 18599137. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.03.088.

- ↑ Bergman BR, Reynolds HR, Skolnick AH, Castillo D (August 2008). "A case of apical ballooning cardiomyopathy associated with duloxetine". Ann. Intern. Med. 149 (3): 218–9. PMID 18678857. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-149-3-200808050-00021.

- ↑ Zamir, M (2005). The Physics of Coronary Blood Flow. Springer Science and Business Media. p. 387. ISBN 978-0387-25297-1.

- ↑ "Mayo Clinic Research Reveals 'Broken Heart Syndrome' Recurs In 1 Of 10 Patients". Medical News Today, MediLexicon International Ltd.

- 1 2 Akashi YJ, Nef HM, Möllmann H, Ueyama T (2010). "Stress cardiomyopathy". Annu. Rev. Med. 61: 271–86. PMID 19686084. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.041908.191750.

- 1 2 Gianni M, Dentali F, et al. (December 2006). "Apical ballooning syndrome or takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a systematic review". European Heart Journal. Oxford University Press. 27 (13): 1523–1529. PMID 16720686. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehl032. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- 1 2 3 Sharkey, S., Lesser, J., & Maron, B. (2011). Takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. American Heart Association. Retrieved from http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/124/18/e460.full

- ↑ "Shock of good news can hurt your heart as much as grief". New Scientist. March 12, 2016.

- ↑ Jelena Ghadri; et al. (March 2016). "Happy heart syndrome: role of positive emotional stress in takotsubo syndrome". European Heart Journal: ehv757. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv757.

- 1 2 3 Azzarelli S, Galassi AR, Amico F, Giacoppo M, Argentino V, Tomasello SD, Tamburino C, Fiscella A (2006). "Clinical features of transient left ventricular apical ballooning". Am J Cardiol. 98 (9): 1273–6. PMID 17056345. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.05.065.

- ↑ Ibáñez B, Navarro F, Farré J, et al. (2004). "[Tako-tsubo syndrome associated with a long course of the left anterior descending coronary artery along the apical diaphragmatic surface of the left ventricle.]". Revista española de cardiología (in Spanish). 57 (3): 209–16. PMID 15056424. doi:10.1016/S1885-5857(06)60138-2.

- ↑ Inoue M, Shimizu M, et al. (2005). "Differentiation between patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy and those with anterior acute myocardial infarction". Circ. J. 69 (1): 89–94. PMID 15635210. doi:10.1253/circj.69.89.

- ↑ Kurisu S, Sato H, Kawagoe T, et al. (2002). "Tako-tsubo-like left ventricular dysfunction with ST-segment elevation: a novel cardiac syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction". American Heart Journal. 143 (3): 448–55. PMID 11868050. doi:10.1067/mhj.2002.120403.

- 1 2 Tsuchihashi K, Ueshima K, Uchida T, Oh-mura N, Kimura K, Owa M, Yoshiyama M, Miyazaki S, Haze K, Ogawa H, Honda T, Hase M, Kai R, Morii I (July 2001). "Transient left ventricular apical ballooning without coronary artery stenosis: a novel heart syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Angina Pectoris-Myocardial Infarction Investigations in Japan". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 38 (1): 11–8. PMID 11451258. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01316-X.

- 1 2 Kawai et al. JPJ 2000

- 1 2 Desmet, WJ; Adriaenssens, BF; Dens, JA (September 2003). "Apical ballooning of the left ventricle: first series in white patients". Heart (British Cardiac Society). 89 (9): 1027–31. PMC 1767823

. PMID 12923018. doi:10.1136/heart.89.9.1027.

. PMID 12923018. doi:10.1136/heart.89.9.1027. - ↑ Abe, Y; Kondo, M; Matsuoka, R; Araki, M; Dohyama, K; Tanio, H (2003-03-05). "Assessment of clinical features in transient left ventricular apical ballooning". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 41 (5): 737–42. PMID 12628715. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02925-X.

- ↑ Merli, E; Sutcliffe, S; Gori, M; Sutherland, GG (January 2006). "Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy: new insights into the possible underlying pathophysiology". European Journal of Echocardiography. 7 (1): 53–61. PMID 16182610. doi:10.1016/j.euje.2005.08.003.

- ↑ Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA, et al. (February 2005). "Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress". N. Engl. J. Med. 352 (6): 539–48. PMID 15703419. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043046.

- 1 2 Elesber, AA; Prasad, A; Lennon, RJ; Wright, RS; Lerman, A; Rihal, CS (July 2007). "Four-Year Recurrence Rate and Prognosis of the Apical Ballooning Syndrome". J Amer Coll Card. 50 (5): 448–52. PMID 17662398. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.050.

- ↑ Bybee KA, Motiei A, Syed IS, Kara T, Prasad A, Lennon RJ, Murphy JG, Hammill SC, Rihal CS, Wright RS (2006). "Electrocardiography cannot reliably differentiate transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome from anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction". J Electrocardiol. 40 (1): 38.e1–6. PMID 17067626. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2006.04.007.

- 1 2 Pilgrim TM, Wyss TR (March 2008). "Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome: A systematic review". Int. J. Cardiol. 124 (3): 283–92. PMID 17651841. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.07.002.

- 1 2 Shimizu M, Kato Y, Masai H, Shima T, Miwa Y (August 2006). "Recurrent episodes of takotsubo-like transient left ventricular ballooning occurring in different regions: a case report". J. Cardiol. 48 (2): 101–7. PMID 16948453.

- ↑ Hurst RT, Askew JW, Reuss CS, Lee RW, Sweeney JP, Fortuin FD, Oh JK, Tajik AJ (August 2006). "Transient midventricular ballooning syndrome: a new variant". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 48 (3): 579–83. PMID 16875987. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.015.

- ↑ Yasu T, Tone K, Kubo N, Saito M (June 2006). "Transient mid-ventricular ballooning cardiomyopathy: a new entity of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy". Int. J. Cardiol. 110 (1): 100–1. PMID 15996774. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.05.060.

- ↑ Dhar S, Koul D, Subramanian S, Bakhshi M (2007). "Transient apical ballooning: sheep in wolves' garb". Cardiol. Rev. 15 (3): 150–3. PMID 17438381. doi:10.1097/01.crd.0000262752.74597.15.

- ↑ Golabchi, A; Sarrafzadegan, N. (2011). "Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or broken heart syndrome: A review article". J. Res. Med. Sci. 16 (3): 340–345.

- ↑ "UOTW #74 - Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. 20 September 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ↑ Akashi YJ, Nakazawa K, Sakakibara M, Miyake F, Koike H, Sasaka K (2003). "The clinical features of takotsubo cardiomyopathy". QJM. 96 (8): 563–73. PMID 12897341. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcg096.

- ↑ Nyui N, Yamanaka O, Nakayama R, Sawano M, Kawai S (2000). "'Tako-Tsubo' transient ventricular dysfunction: a case report". Jpn Circ J. 64 (9): 715–9. PMID 10981859. doi:10.1253/jcj.64.715.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS | Health | Medics 'can mend a broken heart'". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- ↑ Shah, Sandy; Bhimji, Steve (2017). StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 28613549.

- ↑ Derrick, Dawn. "The "Broken Heart Syndrome": Understanding Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy.". Critical Care Nurse.

- ↑ http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/broken-heart-syndrome/treatment

- ↑ Schneider B.; Athanasiadis A.; Sechtem U. (2013). "Gender-Related differences in Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy". Heart Failure Clinics. 9 (2): 137–146. doi:10.1016/j.hfc.2012.12.005.

- ↑ Prasad A, Lerman A, Rihal CS (March 2008). "Apical ballooning syndrome (Tako-Tsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): A mimic of acute myocardial infarction". American Heart Journal. 155 (3): 408–17. PMID 18294473. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2007.11.008.

- ↑ Cebelin, Hirsch (1980). "Human stress cardiomyopathy. Myocardial lesions in victims of homicidal assaults without internal injuries". Human Pathology. 11 (2): 123–32. PMID 7399504.

- ↑ Wittstein I (2007). "The broken heart syndrome". Cleveland Clinical Journal of Medicine. 74 (1): S17–S22. doi:10.3949/ccjm.74.Suppl_1.S17.

- ↑ Tavčar, Ivan (1917). "Cvetje v jeseni" [Blossoms in Autumn] (in Slovene).

- ↑ "Cvetje v jeseni" [Blossoms in Autumn] (in Slovene). 1973.

External links

| Classification |

V · T · D |

|---|---|

| External resources |