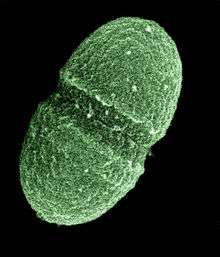

Enterococcus faecalis

| Enterococcus faecalis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Kingdom: | Eubacteria |

| Phylum: | Firmicutes |

| Class: | Bacilli |

| Order: | Lactobacillales |

| Family: | Enterococcaceae |

| Genus: | Enterococcus |

| Species: | E. faecalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Enterococcus faecalis (Andrewes and Horder, 1906) Schleifer and Kilpper-Bälz, 1984 | |

Enterococcus faecalis – formerly classified as part of the group D Streptococcus system – is a Gram-positive, commensal bacterium inhabiting the gastrointestinal tracts of humans and other mammals.[1] Like other species in the genus Enterococcus, E. faecalis can cause life-threatening infections in humans, especially in the nosocomial (hospital) environment, where the naturally high levels of antibiotic resistance found in E. faecalis contribute to its pathogenicity.[1] E. faecalis has been frequently found in root canal-treated teeth in prevalence values ranging from 30% to 90% of the cases.[2] Root canal-treated teeth are about nine times more likely to harbor E. faecalis than cases of primary infections.[3]

Physiology

E. faecalis is a nonmotile microbe; it ferments glucose without gas production, and does not produce a catalase reaction with hydrogen peroxide. It can produce a pseudocatalase reaction if grown on blood agar. The reaction is usually weak. It produces a reduction of litmus milk, but does not liquefy gelatin. It shows consistent growth throughout nutrient broth which is consistent with being an Facultative anaerobe. They catabolize a variety of energy sources including glycerol, lactate, malate, citrate, arginine, agmatine, and many keto acids. Enterococci survive very harsh environments including extremely alkaline pH (9.6) and salt concentrations. They resist bile salts, detergents, heavy metals, ethanol, azide, and desiccation. They can grow in the range of 10 to 45 °C and survive at temperatures of 60 °C for 30 min.[4]

Pathogenesis

E. faecalis can cause endocarditis and septicemia, urinary tract infections, meningitis, and other infections in humans.[5][6] Several virulence factors are thought to contribute to E. faecalis infections. A plasmid-encoded hemolysin, called the cytolysin, is important for pathogenesis in animal models of infection, and the cytolysin in combination with high-level gentamicin resistance is associated with a five-fold increase in risk of death in human bacteremia patients.[7][8][9] A plasmid-encoded adhesin[10] called "aggregation substance" is also important for virulence in animal models of infection.[8][11]

Antibacterial resistance

E. faecalis is resistant to many commonly used antimicrobial agents (aminoglycosides, aztreonam, cephalosporins, clindamycin, the semisynthetic penicillins nafcillin and oxacillin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole). Resistance to vancomycin in E. faecalis is becoming more common.[12][13] Treatment options for vancomycin-resistant E. faecalis include nitrofurantoin (in the case of uncomplicated UTIs),[14] linezolid, and daptomycin, although ampicillin is preferred if the bacteria are susceptible.[15] Quinupristin/dalfopristin can be used to treat Enterococcus faecium but not E. faecalis.[15]

In root canal treatments, NaOCl and chlorhexidine (CHX) are used to fight E. faecalis before isolating the canal. However, recent studies determined that NaOCl or CHX showed low ability to eliminate E. faecalis.[16]

Survival and virulence factors

- Endures prolonged periods of nutritional deprivation

- Binds to dentin and proficiently invades dentinal tubules

- Alters host responses

- Suppresses the action of lymphocytes

- Possesses lytic enzymes, cytolysin, aggregation substance,pheromones, and lipoteichoic acid

- Utilizes serum as a nutritional source

- Resists intracanal medicaments (i.e. Ca(OH)2)

- Maintains pH homeostasis

- Properties of dentin lessen the effect of calcium hydroxide

- Competes with other cells

- Forms a biofilm[4]

Historical

Prior to 1984, enterococci were members of the genus Streptococcus; thus, E. faecalis was known as Streptococcus faecalis.[17]

In 2013, a combination of cold denaturation and NMR spectroscopy was used to show detailed insights into the unfolding of the E. faecalis homodimeric repressor protein CylR2.[18]

Genome structure

The E. faecalis genome consists of 3.22 million base pairs with 3,113 protein-coding genes.[19]

Small RNA

Bacterial small RNAs play important roles in many cellular processes. 11 small RNAs have been experimentally characterised in E. faecalis V583 and detected in various growth phases.[20] Five of them have been shown to be involved in stress response and virulence.[21]

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Enterococcus faecalis. |

- 1 2 Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 294––5. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ Molander, A.; Reit, C.; Dahlén, G.; Kvist, T. (1998). "Microbiological status of root-filled teeth with apical periodontitis". International Endodontic Journal. 31 (1): 1–7. PMID 9823122. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2591.1998.t01-1-00111.x.

- ↑ Rocas, I.; Siqueira, J.; Santos, K. (2004). "Association of Enterococcus faecalis With Different Forms of Periradicular Diseases". Journal of Endodontics. 30 (5): 315–320. doi:10.1097/00004770-200405000-00004.

- 1 2 Stuart, C. H.; Schwartz, S. A.; Beeson, T. J.; Owatz, C. B. (2006). "Enterococcus faecalis: Its role in root canal treatment failure and current concepts in retreatment". Journal of endodontics. 32 (2): 93–8. PMID 16427453. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2005.10.049.

- ↑ Murray, BE. (Jan 1990). "The life and times of the Enterococcus". Clin Microbiol Rev. 3 (1): 46–65. PMC 358140

. PMID 2404568.

. PMID 2404568. - ↑ Hidron AI, Edwards JR, Patel J, et al. (November 2008). "NHSN annual update: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006-2007". Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 29 (11): 996–1011. PMID 18947320. doi:10.1086/591861.

- ↑ Huycke, MM.; Spiegel, CA.; Gilmore, MS. (Aug 1991). "Bacteremia caused by hemolytic, high-level gentamicin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis". Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 35 (8): 1626–34. PMC 245231

. PMID 1929336. doi:10.1128/aac.35.8.1626.

. PMID 1929336. doi:10.1128/aac.35.8.1626. - 1 2 Chow, JW.; Thal, LA.; Perri, MB.; Vazquez, JA.; Donabedian, SM.; Clewell, DB.; Zervos, MJ. (Nov 1993). "Plasmid-associated hemolysin and aggregation substance production contribute to virulence in experimental enterococcal endocarditis". Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 37 (11): 2474–7. PMC 192412

. PMID 8285637. doi:10.1128/aac.37.11.2474.

. PMID 8285637. doi:10.1128/aac.37.11.2474. - ↑ Ike, Y.; Hashimoto, H.; Clewell, DB. (Aug 1984). "Hemolysin of Streptococcus faecalis subspecies zymogenes contributes to virulence in mice". Infect Immun. 45 (2): 528–30. PMC 263283

. PMID 6086531.

. PMID 6086531. - ↑ http://iai.asm.org/content/60/1/25

- ↑ Hirt, H.; Schlievert, PM.; Dunny, GM. (Feb 2002). "In vivo induction of virulence and antibiotic resistance transfer in Enterococcus faecalis mediated by the sex pheromone-sensing system of pCF10". Infect Immun. 70 (2): 716–23. PMC 127697

. PMID 11796604. doi:10.1128/iai.70.2.716-723.2002.

. PMID 11796604. doi:10.1128/iai.70.2.716-723.2002. - ↑ Amyes SG (May 2007). "Enterococci and streptococci". Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 29 Suppl 3: S43–52. PMID 17659211. doi:10.1016/S0924-8579(07)72177-5.

- ↑ Courvalin P (January 2006). "Vancomycin resistance in Gram-positive cocci". Clin. Infect. Dis. 42 Suppl 1: S25–34. PMID 16323116. doi:10.1086/491711.

- ↑ Zhanel GG, Hoban DJ, Karlowsky JA (January 2001). "Nitrofurantoin is active against vancomycin-resistant enterococci". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45 (1): 324–6. PMC 90284

. PMID 11120989. doi:10.1128/AAC.45.1.324-326.2001.

. PMID 11120989. doi:10.1128/AAC.45.1.324-326.2001. - 1 2 Arias, CA.; Contreras, GA.; Murray, BE. (Jun 2010). "Management of multidrug-resistant enterococcal infections". Clin Microbiol Infect. 16 (6): 555–62. PMID 20569266. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03214.x.

- ↑ Estrela, C; Silva, J. A.; De Alencar, A. H.; Leles, C. R.; Decurcio, D. A. (2008). "Efficacy of sodium hypochlorite and chlorhexidine against Enterococcus faecalis--a systematic review". Journal of applied oral science : revista FOB. 16 (6): 364–8. PMC 4327704

. PMID 19082392. doi:10.1590/s1678-77572008000600002.

. PMID 19082392. doi:10.1590/s1678-77572008000600002. - ↑ Schleifer KH, Kilpper-Balz R (1984). "Transfer of Streptococcus faecalis and Streptococcus faecium to the genus Enterococcus nom. rev. as Enterococcus faecalis comb. nov. and Enterococcus faecium comb. nov". Int. J. Sys. Bacteriol. 34: 31–34. doi:10.1099/00207713-34-1-31.

- ↑ Jaremko M, Jaremko L, Kim HY, Cho MK, Schwieters CD, Giller K, Becker S, Zweckstetter M (2013). "Cold denaturation of a protein dimer monitored at atomicresolution". Nat. Chem. Biol. 9 (4): 264–270. PMID 23396077. doi:10.1038/nchembio.1181.

- ↑ Paulsen, IT.; Banerjei, L.; Myers, GS.; Nelson, KE.; Seshadri, R.; Read, TD.; Fouts, DE.; Eisen, JA.; et al. (Mar 2003). "Role of mobile DNA in the evolution of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis". Science. 299 (5615): 2071–4. PMID 12663927. doi:10.1126/science.1080613.

- ↑ Shioya, Kouki; Michaux, Charlotte; Kuenne, Carsten; Hain, Torsten; Verneuil, Nicolas; Budin-Verneuil, Aurélie; Hartsch, Thomas; Hartke, Axel; Giard, Jean-Christophe (2011-01-01). "Genome-wide identification of small RNAs in the opportunistic pathogen Enterococcus faecalis V583". PloS One. 6 (9): e23948. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3166299

. PMID 21912655. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023948.

. PMID 21912655. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023948. - ↑ Michaux, Charlotte; Hartke, Axel; Martini, Cecilia; Reiss, Swantje; Albrecht, Dirk; Budin-Verneuil, Aurélie; Sanguinetti, Maurizio; Engelmann, Susanne; Hain, Torsten (2014-09-01). "Involvement of Enterococcus faecalis Small RNAs in Stress Response and Virulence". Infection and Immunity. 82 (9): 3599–3611. ISSN 0019-9567. PMC 4187846

. PMID 24914223. doi:10.1128/IAI.01900-14.

. PMID 24914223. doi:10.1128/IAI.01900-14.