Street newspaper

Street newspapers (or street papers) are newspapers or magazines sold by homeless or poor individuals and produced mainly to support these populations. Most such newspapers primarily provide coverage about homelessness and poverty-related issues, and seek to strengthen social networks within homeless communities. Street papers aim to give these individuals both employment opportunities and a voice in their community. In addition to being sold by homeless individuals, many of these papers are partially produced and written by them.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries several publications by charity, religious, and labor organizations tried to draw attention to the homeless, but street newspapers only became common after the founding of New York City's Street News in 1989. Similar papers are now published in over 30 countries, with most located in the United States and Western Europe. They are supported by governments, charities, and coalitions such as the International Network of Street Papers and the North American Street Newspaper Association. Although street newspapers have multiplied, many still face challenges, including funding shortages, unreliable staff and difficulty in generating interest and maintaining an audience.

Street newspapers are sold mainly by homeless individuals, but the newspapers vary in how much content is submitted by them and how much of the coverage pertains to them: while some papers are written and published mainly by homeless contributors, others have a professional staff and attempt to emulate mainstream publications. These differences have caused controversy among street newspaper publishers over what type of material should be covered and to what extent the homeless should participate in writing and production. One popular street newspaper, The Big Issue, has been a focus of this controversy because it concentrates on attracting a large readership through coverage of mainstream issues and popular culture, whereas other newspapers emphasize homeless advocacy and social issues and earn less of a profit.

History

Historical foundations

Although the modern street newspaper began with the 1989 publication of Street News in New York City,[1][2] and the Street Sheet in San Francisco, 1989, newspapers sold by the poor and homeless to generate income and to bring attention to social problems date back to the late 19th century; journalism scholar Norma Fay Green has cited The War Cry, created by the Salvation Army in London in 1879, as an early form of "dissident, underground, alternative publication".[3] The War Cry was sold by Salvation Army officers and the working poor to draw people's attention to the poor living conditions of these individuals. Another precursor to the modern street newspaper was Cincinnati's[4][5] Hobo News, which ran from 1915 to 1930[note 1] and featured writing from prominent labor and social activists as well as Industrial Workers of the World members, alongside contributions of oral history, creative writing, and artwork from hoboes, or itinerant beggars.[6] Most street papers published before 1970, such as The Catholic Worker (founded in 1933[7]), were affiliated with religious organizations.[8] Like workers' papers and other forms of alternative media in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, early street newspapers were often created because the founders believed mainstream news did not cover issues that were relevant to ordinary people.[5]

Modern street newspapers

Modern street newspapers began to emerge in the United States in the late 1980s in response to increasing levels of homelessness and homeless advocates' dissatisfaction with the mainstream media's portrayals of the homeless.[9][10] At the time, many media outlets portrayed homeless people as being all criminals and drug addicts, and suggested that homelessness was a result of laziness rather than societal or political factors.[7] Thus, one motivation for the creation of the first street newspapers was to counter the negative coverage of homeless people that was coming from existing media.

Street News, founded in late 1989 in New York City, is frequently cited as the first modern street newspaper.[11][12] Street Sheet in San Francisco started organically around the same time, without the knowledge of Street News' existence, and is considered the longest-running continuously published street newspaper. While some small papers were already being published when it was founded, Street News attracted the most attention and became the "catalyst" for many other papers.[13] Many more street papers were launched in the early 1990s,[2][14][15] crediting the high-profile New York paper as their inspiration, such as Spare Change News in Boston founded in 1992. During this period, an average of five new papers were created every year.[1][8] This growth has been attributed both to changing attitudes and policies towards homeless individuals and to the ease of publishing provided by desktop computers;[1][8][16] After 1989, at least 100 papers[17] sprung up in over 30 countries.[18] By 2008, an estimated 32 million people worldwide read street newspapers, and 250,000 poor, disadvantaged, or homeless individuals sold or contributed to them.[16]

Street papers have been started in many major cities worldwide,[19] mainly in the United States and Western Europe.[20][21] They have especially proliferated in Germany, which in 1999 had more street newspapers than the rest of Europe combined,[21] and in Sweden, where the street papers Aluma, Situation Sthlm and Faktum won the 2006 grand prize award for journalism of the Swedish Publicists' Association.[22][23] Street papers have been established in some cities in Canada, Africa, South America, and Asia.[2][16] Even within the United States, some street newspapers (such as Chicago's bilingual Hasta Cuando) are published in languages other than English.[24]

In the mid-1990s, coalitions were established to strengthen the street newspaper movement. The International Network of Street Papers (INSP) (founded in 1994) and the North American Street Newspaper Association (NASNA) (founded in 1997) aim to provide support for street papers and to "uphold ethical standards".[25] In particular, the INSP was established to help groups that were starting new street newspapers, to bring more mainstream media attention to the street newspaper movement during the 1990s, and to support interaction and cross-talk between street paper publishers and staff from different countries.[26] The INSP and the NASNA voted to combine their resources in 2006;[27] they have collaborated to found the Street News Service, a project which collects articles from member papers and archives them on the internet.[25] National street paper coalitions have also been formed in Europe (there is a national coalition in Italy, and the Netherlands has the Straatmedia Groep Nederland).[21]

Description

Most street newspapers have three main purposes:[7][28]

- To provide income and job skills to the homeless and other marginalized individuals, who act as vendors of and often contributors to the newspapers

- To provide coverage of, and to educate the general public about, issues pertaining to homelessness and poverty

- To establish social networks within homeless communities and between homeless individuals and service providers

The defining characteristic of a street newspaper is that it is sold by homeless or marginalized vendors.[29] While many street newspapers aim to provide coverage of social issues and educate the public about homelessness, this goal is often secondary: many people who buy street newspapers do so to support and express solidarity with the homeless vendor, rather than to read the paper.[30]

The precise demographics of the readership of street newspapers is unclear. A pair of 1993 surveys conducted by Chicago's StreetWise suggested that the paper's readers at the time tended to be college-educated, with slightly over half being female, and slightly over half unmarried.[31]

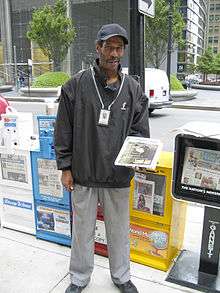

Operations and business

Most street newspapers operate by selling the papers to homeless vendors for a fraction of the retail price (usually between 10% and 50%), after which the vendors sell the papers for the retail price and retain all the proceeds from street sales.[1][8][20][note 2] The income vendors earn from sales is intended to help them "get back on their feet".[8] The purpose of requiring vendors to purchase papers up front and earn back the money by selling them is to help them develop skills in financial management.[32] Vendors for most newspapers are identifiable by badges[33][34] or messenger bags.[33] Many newspapers require that vendors sign a code of conduct[35] or otherwise "clean up their act".[1]

Most street newspaper vendors in the United States and United Kingdom are homeless individuals, although in several other countries (especially in Europe) papers are mainly sold by refugees.[36] Nevertheless, not all vendors are homeless; some have stable housing situations but are unable to hold other jobs, while others started out homeless but were eventually able to use their income from sales to find housing. In general, the major American street newspapers do not require prospective vendors to show proof of homelessness or poverty, and they do not require vendors to retire once they find stable housing.[37] In the United States, since 2008 there have been a growing number of vendors who are "newly needy"—only recently homeless, or with only temporary financial difficulty—as opposed to the "chronically homeless" who have traditionally made up the majority of the vendor force. These vendors are often well-educated and have extensive work experience, but lost their jobs in the 2008 financial crisis.[38]

Street papers start in a variety of ways. Some, such as Street Sense,[17] are begun by homeless or formerly homeless individuals, whereas others are more professional ventures.[20] Many, particularly in the United States, receive aid from local government and charities,[20][39] and coalitions such as the International Network of Street Papers and the North American Street Newspaper Association provide workshops and support for new street papers.[25] Many develop in a bottom-up fashion, starting up through volunteer work and "newcomers to the media business" and gradually expanding to include professionals.[20][40] For most papers, the majority of revenue comes from sales, donations, and government grants, while some receive advertising revenue from local businesses.[20][24][41] There has been some disagreement among street newspaper publishers and supporters over whether papers should accept advertising, with some arguing that advertising is practical and helps support the paper, and others claiming that many kinds of advertisements are inappropriate in a paper that is mainly geared towards the poor.[42]

Specific business models for street newspapers vary widely, ranging from vendor-managed papers that place the highest value upon homeless empowerment and involvement to highly professionalized and commercialized weeklies.[2] Some papers (especially in Europe) operate as autonomous businesses, while others operate as parts of existing organizations or projects.[43] There are papers that are very successful, such as the UK-based The Big Issue, which in 2001 sold nearly 300,000 copies a week and earned the equivalent of 1 million[44]USD in profits, but many papers sell as few as 3,000 copies a month and barely generate a profit at all for the publishers.[2]

Coverage

Most street newspapers report on issues regarding homelessness and poverty,[2] sometimes functioning as a main source of information on policy changes and other practical issues that are relevant to the homeless but may go unreported in mainstream media.[45] Many feature contributions from the homeless and the poor in addition to articles by activists and community organizers,[6][8] including profiles of individual street newspaper vendors.[24][42][46] For example, the first edition of Washington, D.C.'s Street Sense included a description of a prominent homeless community, an interview with a congresswoman, an editorial about the costs and benefits of taking a job, several poems about homelessness, a how-to column, and a section for recipes.[1] A 2009 issue of the Lawrence, Kansas-based Change of Heart included a story on the recent bulldozing of a homeless camp, a review of a book on homelessness, a description of the Family Promise organization for homeless support, and a list of community resources;[47] much of this content was submitted by the homeless.[33] The writing style is often simple and clear; social scientist Kevin Howley describes street newspapers as having a "native eloquence".[48]

According to Howley, street newspapers are similar to citizen journalism in that both are a response to the perceived shortcomings of the mainstream media and both encourage involvement by non-professionals. A major difference between the two, however, is that the citizen journalism movement does not necessarily advocate a particular position, whereas street newspapers openly advocate for the homeless and poor.[49]

Unlike most street newspapers, the UK-based The Big Issue focuses mostly on celebrity news and interviews, rather than coverage of homelessness and poverty.[1] It is still sold by homeless vendors and uses the bulk of its proceeds to support homeless individuals and advocacy organizations for the homeless, but the paper's content is mostly written by professional staff and geared towards a broad audience.[11] Because of its professional nature and high production values, it has been a frequent target of criticism in an ongoing debate between adherents of professional and grassroots ideals of how street newspapers should work.[20][50]

Social benefits

In addition to providing some individuals with income and employment, street newspapers are intended to give homeless participants responsibility and independence, and to create a tight-knit homeless community.[1][51] Many offer additional programs to vendors, such as job training, housing placement assistance, and referral to other direct services. Others operate as a program of a larger social services organization—for instance, Chicago's StreetWise can refer vendors to providers of "drug and alcohol treatment, high school equivalency classes, career counseling, and permanent housing".[1] Most are engaged in some form of organizing and advocacy regarding homelessness and poverty, and many function as "watchdogs" for the local homeless communities.[2] Howley has described street newspapers as a means of mobilizing the networks of "formal and informal relationships that exist between the homeless, the unemployed, and the working poor, and shelter managers, healthcare workers, community organizers, and others who work on their behalf".[6]

Challenges and criticisms

In the early days of street newspapers, people were often reluctant to buy from homeless vendors for fear that they were being scammed.[53] Furthermore, many of the more activist papers fail to sell well because their writing and production are perceived to be unprofessional and lackluster. Topics covered are sometimes seen as lacking newsworthy content, and of little relevance or interest to the general public or the homeless community.[11][54] Organizations in Montreal[11] and San Francisco[54] have responded to these criticisms by offering workshops in writing and journalism for homeless contributors. Papers such as StreetWise have in the past been criticized as "grim" and for having vendors that are too loud and intrusive.[55] Some newspapers sell well but may not be widely read, as many people will donate to vendors without buying, or buy the newspaper and then throw it away.[30][52][56] Howley has described readers' hesitance or unwillingness to read the papers as "compassion fatigue".[57] On the other hand, those papers that do sell well and are widely read, such as The Big Issue, are often targets of criticism for being too "mainstream" or commercial.[11][58]

Other difficulties street newspapers face include high turnover of "transient" or unreliable staff,[11][57][59] lack of adequate funding,[11][24][41] lack of journalistic freedom for papers that are funded by local government, and, among some demographics, lack of interest in homeless issues. For example, journalism professor Jim Cunningham has attributed the difficulties in selling Calgary's Calgary Street Talk to the fact that the mostly middle-class, conservative population has "not enough sensitivity to the causes of homelessness".[11] Finally, anti-homeless legislation often targets street newspapers and vendors; for example, in New York City and Cleveland, laws have prevented vendors from selling papers on public transit or other high-traffic areas, making it difficult for the papers Street News and Homeless Grapevine to earn revenue.[24]

Differing approaches

Among proponents and publishers of street newspapers there is disagreement over how street newspapers should be run and what their goals should be, reflecting a "clash between two philosophies for advocating social change".[50] On one side of the debate are papers that seek to function like a business and generate a profit and a wide readership in order to benefit the homeless in a practical way; on the other are papers that seek to provide a "voice" to the homeless and poor without watering down their message for a broad readership.[50] Timothy Harris, the director of Real Change, has described the two camps as "liberal entrepreneurial" and "radical, grassroots activist".[13]

Controversy surrounding The Big Issue, the world's most widely circulated street newspaper,[11][12] is a good example of these two schools of thought.[note 3] The Big Issue is mostly a tabloid covering celebrity news; while it is sold by the homeless and generates a profit that is used to benefit the homeless, the content is not written by them and there is little coverage of social issues that are relevant to them.[1] In the late 1990s when the London-based paper began making plans to enter markets in the United States, many American street newspaper publishers reacted defensively, saying they could not compete with the production values and mainstream appeal of the professionally produced The Big Issue[2][50] or that The Big Issue did not do enough to provide a voice to the homeless.[60] The reaction to The Big Issue raised what is now an ongoing conflict between commercialized, professional papers and more grassroots-style ones,[12][20] with papers such as The Big Issue emulating mainstream papers and magazines in order to generate a large profit to invest in homeless issues and others focusing on political and social issues rather than on content that will generate money.[2] Some street newspaper proponents believe that the primary aim of the papers should be to give homeless individuals a voice and to "fill the void"[10] in mainstream media coverage, whereas others believe it should be to provide homeless individuals with jobs and an income.[50]

Other frequent areas of disagreement include the extent that the homeless should participate in the writing and printing of street newspapers,[11] and whether street newspapers should accept advertising to generate revenue.[42] Kevin Howley sums up the division between different street newspaper models when he questions if it is "possible (or desirable for that matter) to publish a dissident newspaper—that is, a publication committed to progressive social change—and still attract a wide audience".[50]

List of street newspapers

Notes

- ↑ Another author claims the paper had a shorter lifespan, running "from the late 1910s to the early 1920s" (Heinz 2004, p. 534).

- ↑ Some street newspapers, however, work differently, having vendors pay back a portion of the proceeds after selling the paper (Corporal 2008).

- ↑ Although The Big Issue has attracted attention and controversy because of its stature, it is not the only street newspaper that follows a business-oriented model. Numerous street newspapers work in a similar way, with The Big Issue being the most well-known example of a whole category of street newspapers (Green 1998, p. 47).

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Harman, Danna (17 November 2003). "Read all about it: street papers flourish across the US". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 13 January 2009. Archived version

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Boukhari, Sophie (1999). "The press takes to the street". The UNESCO Courier. UNESCO. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- ↑ Howley 2005, p. 62

- ↑ Dodge, Chris (1999). "Words on the Street: Homeless People's Newspapers". American Libraries. Archived from the original on 2009-03-17. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- 1 2 Heinz 2004, p. 534

- 1 2 3 Howley 2005, p. 63

- 1 2 3 Heinz 2004, p. 535

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "About Street Papers". North American Street Newspaper Association. 7 November 2008. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ↑ Howley 2003, p. 1

- 1 2 Green 1998, p. 47

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Brown 2002

- 1 2 3 Heinz 2004, p. 536

- 1 2 Harris, Timothy (14 September 1997). "Strength in Unity: Street Newspaper Must Not Be Its Own Enemy". Founding Conference of the North American Street Newspaper Association. Real Change. Archived from the original on 3 November 2005. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- ↑ "Get Acquainted". Coalition on Homelessness, San Francisco. Retrieved 13 January 2009.

- ↑ "The Big Issue History". The Big Issue. Archived from the original on 1 March 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2009.

- 1 2 3 Corporal, Lynette Lee (13 November 2008). "Jobs Come Aboard ‘Jeepney’ Street Paper". Asia Media Forum. Retrieved 12 February 2009. Alternate link Archived 2009-01-14 at the Wayback Machine..

- 1 2 "Street News (transcript)". The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer. Public Broadcasting Service. 15 December 2004. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ↑ The International Network of Street Papers alone has 94 member papers across 36 countries. "Our Street Papers". International Network of Street Papers. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ↑ Howley 2003, p. 2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Magnusson, Jan A. "The transnational street paper movement". Situation Sthlm. Archived from the original on 29 June 2006. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- 1 2 3 Hanks & Swithinbank 1999, p. 154

- ↑ Holender, Robert (22 May 2006). "De hemlösas tidningar prisades". Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ↑ "Röster åt utsatta fick publicistpris". Ekot (in Swedish). Sveriges Radio. 22 May 2006. Archived from the original on 14 June 2006. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Heinz 2004, p. 538

- 1 2 3 Heinz 2004, p. 539

- ↑ Hanks & Swithinbank 1999, pp. 155–6

- ↑ Harris, Timothy (5 October 2006). "Director's Corner". Real Change News. Archived from the original on September 29, 2006. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ↑ "The street paper concept". International Network of Street Papers. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ↑ Calhoun, Patricia (18 February 2009). "Meet the MasterMind Class of 2009". Westword. Retrieved 12 March 2009.

- 1 2 Torck 2001, p. 372

- ↑ Green 1998, p. 42

- ↑ "How We Work". The Big Issue. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- 1 2 3 Condron, Courtney (23 August 2007). "Lawrence Streetpaper receives grant". University Daily Kansan. Retrieved 13 January 2009.

- ↑ "About StreetWise Vendors". StreetWise. Archived from the original on February 9, 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2009.

- ↑ Such as The Big Issue: "How We Work". The Big Issue. Retrieved 13 January 2009.

- ↑ Hanks & Swithinbank 1999, pp. 153–4

- ↑ Hsu, Huan (10 April 2007). "Not All the Peddlers of Seattle's Homeless Paper Are Homeless". Seattle Weekly. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ↑ Lorber, Janie (12 April 2009). "Extra, Extra! Homeless Lift Street Papers, and Attitudes". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 April 2009.

- ↑ Roy, M.G. (7 December 2006). "Sweets on the Street: Change of Heart, Lawrence's homeless newspaper is ten years old this year". The Lawrencian. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ↑ Green 1998, p. 38

- 1 2 Green 1998, pp. 41–2

- 1 2 3 Howley 2003, p. 9

- ↑ Hanks & Swithinbank 1999, p. 155

- ↑ https://beta.companieshouse.gov.uk/company/06771432/filing-history

- ↑ Howley 2003, p. 8

- ↑ Green 1998, pp. 43–4

- ↑ Ed. Craig Sweets. Change of Heart: A voice for Lawrence's Homeless People. Vol. 12, no. 1 (Winter 2009).

- ↑ Howley 2005, p. 64

- ↑ Howley 2003, pp. 1–2; 7

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Howley 2003, p. 11

- ↑ Stringer, Lee, Grand Central Winter: Stories from the Street, 1st ed., New York : Seven Stories Press, 1998. ISBN 1-888363-57-6. Cf. Chapter 6, "West Forty-sixth Street, Winter 1989" which is about his experiences as a vendor of Street News. "But it's not just the easy money. For most of us vendors this old Blimpie's was like our clubhouse. We lingered here when we came for papers, milled around, worked the winter chill from our bones, traded stories of the street."

- 1 2 Green, Sara Jean (1 February 2005). "Real Change's transformation includes plan to reach readers". Seattle Times. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- ↑ Green 1998, p. 36

- 1 2 "Homeless Journalists Hone Their Reporting Skills". American News Service, n.d. in Heinz 2004.

"[Street newspapers] have traditionally been long on personal essays and short on hard news". - ↑ Green 1998, pp. 40–1

- ↑ Green 1998, pp. 36; 40

- 1 2 Howley 2003, p. 10

- ↑ Jacobs, Sally, "News is Uplifting for Homeless in N.Y.", The Boston Globe, May 7, 1990

- ↑ Green 1998, p. 46

- ↑ Messman, Terry (10 February 1998). "The Big Issue means big business as usual". Street Spirit. Homeless People's Network. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

Bibliography

- Brown, Ann M. (2002). "Small Papers, Big Issues". Ryerson Review of Journalism. Archived from the original on September 11, 2007. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- Green, Norma Fay (1998). "Chicago's StreetWise at the Crossroads: A Case Study of a Newspaper to Empower the Homeless in the 1990s". Print Culture in a Diverse America. eds. James Philip Danky, Wayne A. Wiegand. University of Illinois Press. pp. 34–55. ISBN 0-252-06699-5.

- Green, Norma Fay (23 July 1999). "Trying to write a history of the role of street newspapers in the social movement to alleviate poverty and homelessness". 4th conference of North American Street Newspaper Association. Street Paper Focus Group. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- Hanks, Sinead; Swithinbank, Tessa (1999). "The Big Issue and other street papers: a response to homelessness". Environment and Urbanization. 9 (1): 149–158. doi:10.1177/095624789700900112.

- Heinz, Teresa L. (2004). "Street Newspapers". In David Levinson. Encyclopedia of Homelessness. SAGE Publications. pp. 534–9. ISBN 0-7619-2751-4.

- Howley, Kevin (2003). "A Poverty of Voices: Street Papers as Communicative Democracy". Journalism. 4 (3): 273–292. doi:10.1177/14648849030043002.

- Howley, Kevin (2005). Community Media: People, Places, and Communication Technologies. Cambridge University Press. pp. 62–4. ISBN 0-521-79228-2.

- Jefferson, David J. (March 11, 2010). "Spare Change's Most Insidious Myths". Spare Change News. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Homeless Empowerment Project. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011.

- Torck, Danièle (2001). "Voices of Homeless People in Street Newspapers: A Cross-Cultural Exploration". Discourse and Society. 12 (3): 271–392. doi:10.1177/0957926501012003005.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Street papers. |

- Street News Service, aggregator of articles from street newspapers

- International Network of Street Papers

- North American Street Newspaper Association

- Street Paper Focus Group at the University of Washington