Streamline Moderne

Streamline Moderne, or Art Moderne, is a late type of the Art Deco architecture and design that emerged in the 1930s. Its architectural style emphasized curving forms, long horizontal lines, and sometimes nautical elements.[1]

Background

The first streamline buildings evolved from the work of New Objectivity artists, a movement connected to the German Werkbund, that was initiated by Hermann Muthesius (see e.g. Mossehaus).

As the Great Depression of the 1930s progressed, Americans saw a new aspect of Art Deco—i.e., streamlining, a concept first conceived by industrial designers who stripped Art Deco design of its ornament in favor of the aerodynamic pure-line concept of motion and speed developed from scientific thinking. Cylindrical forms and long horizontal windowing also may be influenced by constructivism. As a result, an array of designers quickly ultra-modernized and streamlined the designs of everyday objects. Manufacturers of clocks, radios, telephones, cars, furniture, and many other household appliances embraced the concept.

The style was the first to incorporate electric light into architectural structure. In the first-class dining room of the SS Normandie, fitted out 1933–35, twelve tall pillars of Lalique glass, and 38 columns lit from within illuminated the room. The Strand Palace Hotel foyer (1930), preserved from demolition by the Victoria and Albert Museum during 1969, was one of the first uses of internally lit architectural glass, and coincidentally was the first Moderne interior preserved in a museum.

The Streamline Moderne was both a reaction to Art Deco and a reflection of austere economic times; Sharp angles were replaced with simple, aerodynamic curves. Exotic woods and stone were replaced with cement and glass.

Art Deco and Streamline Moderne were not necessarily opposites. Streamline Moderne buildings with a few Deco elements were not uncommon but the prime movers behind streamline design (Raymond Loewy, Walter Dorwin Teague, Gilbert Rohde, Norman Bel Geddes) all disliked Art Deco, seeing it as effete and falsely modern—essentially a fraud.

PWA Moderne was a related style in the United States of buildings completed between 1933 and 1944 as part of relief projects sponsored by the Public Works Administration (PWA) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

Characteristics

Common characteristics of Streamline Moderne and Art Moderne

- Horizontal orientation

- Rounded edges, corner windows

- Glass brick walls

- Porthole windows

- Chrome hardware

- Smooth exterior wall surfaces, usually stucco (smooth plaster finish)

- Flat roof with coping

- Also no roof at all, with no coping.

- Horizontal grooves or lines in walls

- Subdued colors: base colors were typically light earth tones, off-whites, or beiges; and trim colors were typically dark colors (or bright metals) to contrast from the light base

The Normandie Hotel, which opened during 1942, is built in the stylized shape of the ocean liner SS Normandie, and it includes the ship's original sign. The Sterling Streamliner Diners were diners designed like streamlined trains.

Although Streamline Moderne houses are less common than streamline commercial buildings, residences do exist. The Lydecker House in Los Angeles, built by Howard Lydecker, is an example of Streamline Moderne design in residential architecture. In tract development, elements of the style were frequently used as a variation in postwar row housing in San Francisco's Sunset District.

Industrial design

The style was applied to appliances such as electric clocks, sewing machines, small radio receivers and vacuum cleaners. Their manufacturing processes exploited developments in materials science including aluminium and bakelite. Compared to Europe, the United States in the 1930s had a stronger focus on design as a means to increase sales of consumer products. Streamlining was associated with prosperity and an exciting future. This hope resonated with the American middle class, the major market for consumer products. A wide range of goods from refrigerators to pencil sharpeners was produced in streamlined designs.

Streamlining became a widespread design practice for automobiles, railroad cars, buses, and other vehicles in the 1930s. Notable automobile examples include the 1934 Chrysler Airflow, the 1950 Nash Ambassador "Airflyte" sedan with its distinctive low fender lines, as well as Hudson's postwar cars, such as the Commodore, that "were distinctive streamliners—ponderous, massive automobiles with a style all their own".[2]

Streamline style can be contrasted with functionalism, which was a leading design style in Europe at the same time. One reason for the simple designs in functionalism was to lower the production costs of the items, making them affordable to the large European working class.[3] Streamlining and functionalism represent two very different schools in modernistic industrial design, but both reflecting the intended consumer.

1921 The Rumpler Tropfenwagen was to be the first streamlined car.

1921 The Rumpler Tropfenwagen was to be the first streamlined car. 1922 Aurel Persu automobile was the first car to have the wheels inside its aerodynamic line.

1922 Aurel Persu automobile was the first car to have the wheels inside its aerodynamic line.- 1934 Tatra 77 is the first serial-produced truly aerodynamically designed automobile.

1939 Schlörwagen - Subsequent wind tunnel tests yielded a drag coefficient of only 0.113. Incredible then and still extremely impressive today.

1939 Schlörwagen - Subsequent wind tunnel tests yielded a drag coefficient of only 0.113. Incredible then and still extremely impressive today. 1929: The Schienenzeppelin or rail zeppelin was an experimental railcar which resembled a zeppelin airship in appearance. It accelerated the railcar to 230.2 km/h (143 mph) setting the land speed record for a petrol powered rail vehicle.

1929: The Schienenzeppelin or rail zeppelin was an experimental railcar which resembled a zeppelin airship in appearance. It accelerated the railcar to 230.2 km/h (143 mph) setting the land speed record for a petrol powered rail vehicle. 1934 Chrysler Airflow

1934 Chrysler Airflow 1948 Hudson Commodore

1948 Hudson Commodore

1958 Airstream travel trailer

1958 Airstream travel trailer New York Central steam locomotive restyled by industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss, 1938

New York Central steam locomotive restyled by industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss, 1938- Santa Fe Railway's San Francisco Chief, a late 1940s streamlined design with paint scheme dating from the late 1930s

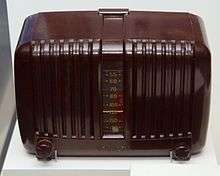

Bakelite radio

Bakelite radio.jpg)

Notable examples

In architecture and design

- 1923 Mossehaus, Berlin. Reconstruction by Erich Mendelsohn and Richard Neutra

- 1926: Long Beach Airport Main Terminal, Long Beach, California

- 1928: Lockheed Vega, designed by John Knudsen Northrop, a six-passenger, single-engine aircraft used by Amelia Earhart

- 1928-1930: Canada Permanent Trust Building, Toronto

- 1930: Strand Palace Hotel, London; foyer designed by Oliver Percy Bernard

- 1930: Maison de la radio, Place Flagey, Brussels, by Joseph Diongre

- 1930-1934: Broadway Mansions, Shanghai, designed by B. Flazer of Palmer and Turner

- 1931: The Eaton's Seventh Floor in Toronto, Canada, designed by Jacques Carlu, in the former Eaton's department store

- 1931: Napier, New Zealand, rebuilt in Art Deco and Streamline Moderne styles after a major earthquake

- 1931-1933: Hamilton GO Station, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada by Alfred T. Fellheimer

- 1932: Edifício Columbus, São Paulo, Brazil (demolished 1971)

- 1933: Casa della Gioventù del Littorio, designed by Luigi Moretti, Rome

- 1933: Ty Kodak building in Quimper, France, designed by Olier Mordrel

- 1933: Southgate tube station, London

- 1933: Burnham Beeches in Sherbrooke, Victoria, Australia. Harry Norris architect

- 1933: Merle Norman Building, Santa Monica, California See also History of Santa Monica, California

- 1933: Midland Hotel, Morecambe, Morecambe, England

- 1933: Edificio Lapido, Montevideo, Uruguay

- 1933–1940: Interior of Chicago's Museum of Science and Industry, designed by Alfred Shaw

- 1934: Pioneer Zephyr, the first of Edward G. Budd's streamlined stainless-steel locomotives

- 1934: Tatra 77, the first mass-market streamline automotive design

- 1934: Chrysler Airflow, the second mass-market streamline automotive design

- 1934: Hotel Shangri-La (Santa Monica), California

- 1934: Edifício Nicolau Schiesser, São Paulo, Brazil (demolished 2014)

- 1935: Jubilee Pool (Penzance, Cornwall), England

- 1935: Ford Building (San Diego, California), Balboa Park

- 1935: The De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea, England

- 1935: Pan Pacific Auditorium, Los Angeles

- 1935: Edificio Internacional de Capitalización, Mexico City, Mexico

- 1935: The Hindenburg, Zeppelin passenger accommodations

- 1935: The interior of Lansdowne House on Berkeley Square in Mayfair, London

- 1935: The Hamilton Hydro-Electric System Building, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

- 1935: MV Kalakala, the world's first streamlined ferry

- 1935-1956: High Tower Court, Hollywood Heights, Los Angeles[7]

- 1936: Lasipalatsi, in Helsinki, Finland, functionalist office building and now a cultural and media center

- 1936: Florin Court, on Charterhouse Square in London, built by Guy Morgan and Partners

- 1936: Campana Factory, historic factory in Batavia, Illinois.

- 1936: Edifício Guarani, São Paulo, Brazil

- 1937: Regent Court, residential apartments on Bradfield Road, Hillsborough, Sheffield

- 1937: Malloch Building, residential apartments at 1360 Montgomery Street in San Francisco

- 1937: B and B Chemical Company, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, built by Coolidge, Shepley, Bulfinch & Abbott

- 1937: Belgium Pavilion, at the Exposition Internationale, Paris

- 1937: TAV Studios (Brenemen's Restaurant), Hollywood

- 1937: Hecht Company Warehouse, Washington, D.C.

- 1937: Minerva (or Metro) Theatre and the Minerva Building, Potts Point, New South Wales, Australia

- 1937: Bather's Building in the Aquatic Park Historic District, now the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park Maritime Museum

- 1937: Barnum Hall (High School auditorium), Santa Monica, California

- 1937: J.W. Knapp Company Building (department store) Lansing, Michigan

- 1937: Wan Chai Market, Wan Chai, Hong Kong

- 1937: River Oaks Shopping Center, Houston

- 1937: Toronto Stock Exchange Building, mix of Art Deco and Streamline Moderne

- 1937: Pittsburgh Plate Glass Enamel Plant, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, by Alexander C. Eschweiler

- 1938: Mark Keppel High School, Alhambra, California

- 1938: Normandie building, Mar del Plata

- 1938: Danum House, Doncaster, England

- 1938: 20th Century Limited, New York City

- 1938: Jones Dog & Cat Hospital, West Hollywood, California, by Wurdeman & Beckett (remodel of 1928 original construction)[8]

- 1939: Bartlesville High School, Bartlesville, Oklahoma

- 1939: Coca-Cola Building (Los Angeles), California

- 1939: First Church of Deliverance, Chicago, Illinois

- 1939: Marine Air Terminal, LaGuardia Airport, New York City

- 1939: Road Island Diner, Oakley, Utah

- 1939: Pennsylvania Railroad PRR S1 streamlined steam train, designed by Raymond Loewy

- 1939: New York World's Fair

- 1939: Cardozo Hotel, Ocean Drive, South Beach, Miami Beach, Florida

- 1939: Royer Building in Ephrata, Pennsylvania

- 1939: Daily Express Building, Manchester, England

- 1939: East Finchley tube station, London, England

- 1940: Gabel Kuro jukebox designed by Brooks Stevens

- 1940: Ann Arbor Bus Depot, Michigan

- 1940: Jai Alai Building, Taft Avenue Manila, Philippines (demolished 2000)

- 1940: Hollywood Palladium, Los Angeles, California

- 1940: Las Vegas Union Pacific Station, Las Vegas, Nevada

- 1941: Avalon Hotel, Ocean Drive, South Beach, Miami Beach, Florida

- 1942: Normandie Hotel in San Juan, Puerto Rico

- 1942: Mercantile National Bank Building, Dallas

- 1943: Edifício Trussardi in São Paulo, Brazil

- 1944: Huntridge Theater, Las Vegas, Nevada

- 1946: Gerry Building, Los Angeles, California

- 1946: Canada Dry Bottling Plant, Silver Spring, Maryland

- 1946: Broadway Theatre, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

- 1947: Sears Building, Santa Monica, California

- 1948: Greyhound Bus Station, Cleveland

- 1949: Sault Memorial Gardens, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario

- 1949: Varsity Theatre, Davis, California

- 1950: Ocean Terminal, Southampton, England (demolished 1983)

- 1951: Federal Reserve Bank Building, Seattle, Washington

- 1954: Poitiers Theater designed by Edouard Lardillier

- 1955: Iowa State Bank & Trust Building, Fairfield[9]

- 1955: Aetna Building (former Prudential Life Insurance Building), Jacksonville, Florida, designed by KBJ Architects

- 1957–2006: Star Ferry Pier, Central, Hong Kong (demolished)

- 1957: Tsim Sha Tsui Ferry Pier, Hong Kong

- 1965: Hung Hom Ferry Pier, Hong Kong

- 1968-2014: Wan Chai Pier, Hong Kong (demolished)

In motion pictures

- Aircraft and buildings in William Cameron Menzies's 1936 movie Things to Come

- The buildings in Frank Capra's 1937 movie Lost Horizon, designed by Stephen Goosson

- The design of the "Emerald City" in the 1939 movie The Wizard of Oz

- The main character's helmet and rocket pack in the 1991 movie The Rocketeer

- The High Tower apartments, featured in the 1973 film The Long Goodbye and 1991 film Dead Again[7]

- The Malloch Apartment Building at 1360 Montgomery St, San Francisco that serves as apartment for Lauren Bacall's character in Dark Passage

See also

- Art Deco

- Constructivist architecture

- Raygun Gothic

- Googie architecture

- Century of Progress Chicago's second World's Fair (1933–34)

- Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (1937) (1937 Paris Exposition)

- PWA Moderne - a Moderne style in the United States completed between 1933 and 1944 as part of relief projects sponsored by the Public Works Administration (PWA) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA)

References

- ↑ "A true example of Streamline Moderne". Times of Malta. 6 September 2012. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016.

- ↑ Reed, Robert C. (1975). The Streamline Era. San Marino, CA: Golden West Books. ISBN 0-87095-053-3. OCLC 1339849.

- ↑ Nickelsen, Trine (15 June 2010). "Aluminium – en kulturhistorie" (in Norwegian). Apollon. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ↑ "Why Nash?". N.A.D.A. Magazine: 28–29 and 45. 1949. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

Nash has gone farthest in functional design, to derive the fullest benefits of modern streamlining principles.

- ↑ Mcclurg, Bob (2016). History of AMC motorsports. Car Tech. p. 18. ISBN 9781613251775. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

- ↑ "20.7% Less Air Drag! (Nash Airflyte advertisement)". Life. 28 (2). January 9, 1950. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

- 1 2 Bettsky, Aaron (15 July 1993). "A Hollywood Ending for Those Who Take This Elevator to the Top". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ↑ Bos, Sascha (16 July 2014). "Historic 1938 Building Could Complicate Massive WeHo Development". LA Weekly. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ↑ Lipman, Jonathan; Wright, Frank Lloyd (2003). Frank Lloyd Wright and the Johnson Wax Buildings. Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486427485. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Streamline Moderne architecture. |

- Streamline Moderne, Flickr

- Streamline Moderne, Decopix

- "Streamline Moderne & Nautical Moderne Architecture in Miami Beach", Miami Beach Magazine

- "San Francisco 1939 Modern 'Wedding Cake'", HGTV.com