Watling Street

Coordinates: 52°39′22.5″N 1°55′37.7″W / 52.656250°N 1.927139°W

| Watling Street | |

|---|---|

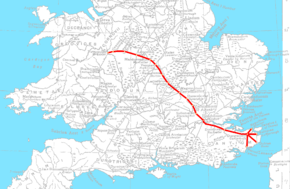

|

A map of the Saxon Watling Street overlaid on the Roman road network | |

| Route information | |

| Length: |

276 mi (444 km) [230 mi (370 km) Rutupiae to Viroconium |

| Time period: |

Roman Britain Saxon Britain |

| Major junctions | |

| From: | The Kentish ports |

| Canterbury, London, St Albans | |

| To: | Wroxeter |

Watling Street is a route in England and Wales that began as an ancient trackway first used by the Britons, mainly between the areas of modern Canterbury and St Albans using a natural ford near Westminster. The Romans later paved the route, which then connected the Kentish ports of Dubris (Dover), Rutupiae (Richborough), Lemanis (Lympne), and Regulbium (Reculver) to their bridge over the Thames at Londinium (London). The route continued northwest past Verulamium (St Albans) on its way to Viroconium (Wroxeter). The Romans considered the continuation on to Blatobulgium (Birrens) beyond Hadrian's Wall to be part of the same route, leading some scholars to call this Watling Street as well, although others restrict it to the southern leg. Watling Street was the site of Boudica's defeat by the Romans and was later the southwestern border of the Danelaw. In the early 19th century, the course between London and the Channel was paved and became known as the Great Dover Road: today, the route from Dover to London forms part of the A2 road. The route from London to Wroxeter forms much of the A5 road. At various points along the historic route, the name Watling Street remains in modern use.

Name

The original Celtic and Roman name for the road is unknown and the Romans may not have viewed it as a single path at all, dividing it amongst two separate itineraries in one 2nd-century list. The modern name instead derives from the Old English Wæcelinga Stræt, from a time when "street" (Latin: via strata) referred to any paved road and had no particular association with urban thoroughfares. The Waeclingas ("people of Waecla")[1] were a tribe in the St Albans area in the early medieval period[1][2] with an early name of the town being ‘Waetlingacaester’ which would translate into modern English as ‘Watlingchester’.

It is uncertain whether they were considered part of Middlesex or Essex or a British remnant (wæcla being a possible variation of Old English wealhas, "foreigners", which gave the Welsh their English name).

The original Anglo-Saxon name for the section of the route between Canterbury and London was Casingc Stræt or Key Street, a name still borne by a hamlet on the road near Sittingbourne.[3] This section only later became considered part of Watling Street.[3]

Used as a boundary

Watling Street has been used as a boundary of many historic administrative units, and some of these are still in existence today, either through continuity or the adoption of these as by successor areas. Examples include:

- Watling Street was used as a boundary in the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum and it is often inferred that this made the road the SW boundary of the Danelaw

- It is the boundary of Leicestershire and Warwickshire, this may be a legacy of the treaty described above.

- Watling Street forms part of the boundary of four London Boroughs (Harrow, Brent, Camden and Barnet) and is sometimes described as the boundary of West and North London.

History

British

The broad, grassy trackway found by the Romans had already been used by the Britons for centuries. The main path led from Richborough on the English Channel to a natural ford in the Thames at Thorney Island[4] near Westminster to a site near Wroxeter, where it split. The western continuation went on to Holyhead while the northern ran to Chester and on to the Picts in Scotland.[5]

Roman

The Romans began constructing paved roads shortly after their invasion in AD 43. The London portion of Watling Street was rediscovered during Christopher Wren's rebuilding of St Mary-le-Bow in 1671–73, following the Great Fire. Modern excavations date its construction to the winter from AD 47 to 48. Around London, it was 7.5–8.7 m (25–29 ft) wide and paved with gravel. It was repeatedly redone, including at least twice before the sack of London by Boudica's troops in 60 or 61.[6] The road ran straight from the bridgehead on the Thames[7] to what would become Newgate on the London Wall before passing over Ludgate Hill and the Fleet and dividing into Watling Street and the Devil's Highway west to Calleva (Silchester). Some of this route is preserved beneath Old Kent Road.[8]

The 2nd-century Antonine Itinerary gives the course of Watling Street from "Urioconium" (Wroxeter) to "Portus Ritupis" (Richborough) as a part of its Second Route (Iter II), which runs for 501 MP from Hadrian's Wall to Richborough:[9][10]

Battle

Some site in the middle section of this route is assumed by most historians to have been the location of G. Suetonius Paulinus's victory over Boudica's Iceni in AD 61.

Subsidiary routes

The two routes of the Antonine Itinerary immediately following (Iter III & IV) list the stations from Londinium to "Portus Dubris" (Dover) and to "Portus Lemanis" (Lympne) at the western edge of the Romney Marsh, suggesting that they may have been considered interchangeable terminuses. They only differ in the distance to Durovernum: 14 and 17 Roman miles, respectively.[9][10] The route to Lemanis was sometimes distinguished by the name "Stone Street"; it now forms most of the B2068 road that runs from the M20 motorway to Canterbury. The route between Durovernum and the fortress and port at Regulbium (Reculver) on Kent's northern shore is not given in these itineraries but was also paved and is sometimes taken as a fourth terminus for Watling Street. The Sixth Route (Iter VI) also recorded an alternate path stopping at Tripontium (Newton and Biggin) between Venonis (High Cross) and Bannaventa (Norton); it is listed as taking 24 Roman miles rather than 17.[9][10]

The more direct route north from Londinium (London) to Eboracum (York) was Ermine Street. The stations between Eboracum and Cataractonium (Catterick) were shared with Dere Street, which then branched off to the northeast. Durocobrivis (Dunstable) was the site of the path's intersection with the Icknield Way. The Maiden Way ran from Bravoniacum (Kirkby Thore) to the lead and silver mines at Epiacum (Whitley Castle) and on to Hadrian's Wall.

Saxon

By the time of the Saxon invasions, the Roman bridge across the Thames had presumably fallen into disrepair or been destroyed. The Saxons abandoned the walled Roman site in favour of Lundenwic to its west, presumably because of its more convenient access to the ford on the Thames. They did not return to Lundenburh (the City of London) until forced to do so by the Vikings in the late 9th century. Over time, the graveling and paving itself fell into disrepair, although the road's course continued to be used in many places as a public right of way. "Watlingestrate" was one of the four roads (Latin: chemini) protected by the king's peace in the Laws of Edward the Confessor.[11][12]

A number of Old English names testify to route of Watling Street at this time: Boughton Street in Kent; Colney Street in Hertfordshire; Fenny Stratford and Stony Stratford in Buckinghamshire; Old Stratford in Northamptonshire; Stretton under Fosse and Stretton Baskerville in Warwickshire; the three adjacent settlements of All Stretton, Church Stretton, and Little Stretton in Shropshire; and Stretton Sugwas in Herefordshire.

Viking

Following the Viking invasions, the 9th-century Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum mentions Watling Street as a boundary.

Norman

It is assumed that the pilgrims in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales used the southeastern stretch of Watling Street when journeying from Southwark to Canterbury.

Modernity

The first turnpike trust in England was established over Watling Street northwest of London by an Act of Parliament on 4 March 1707 in order to provide a return on the investment required to once more pave the road.[13] The section from Fourne Hill north of Hockliffe to Stony Stratford was paved at a cost of £7000[lower-alpha 1] over the next two years. Revenue was below expectations; in 1709, the trust succeeded in getting a new act extending the term of their monopoly but not permitting their tolls to be increased. In 1711, the trust's debts had not been discharged and the creditors took over receivership of the tolls. In 1716, a new act restored the authority of the trust under the supervision of another group appointed by the Buckinghamshire justices of the peace. The trust failed to receive a further extension of their rights in 1736 and their authority ended at the close of 1738. In 1740, a new act named new trustees to oversee the road, which the residents of Buckinghamshire described as being "ruined".[14]

The road was again paved in the early 19th century at the expense of Thomas Telford. He operated it as a turnpike road for mail coaches from Ireland. To this purpose, he extended it to the port of Holyhead on Anglesey in Wales. During this time, the section southeast of London became known as the Great Dover Road. The tolls ended in 1875.

Much of the road is still in use today, apart from a few sections where it has been diverted. The A2 road between Dover and London runs over or parallel to the old path. A section of Watling Street still exists in the City of London close to Mansion House underground station on the route of the original Roman road which traversed the River Thames via the first London Bridge and ran through the City in a straight line from London Bridge to Newgate.[15] The sections of the road in Central London possess a variety of names, including Edgware Road and Maida Vale. At Blackheath, the Roman road ran along Old Dover Road, turning and running through the area of present-day Greenwich Park to a location perhaps a little north of the current Deptford Bridge. The stretch between London and Shrewsbury (continuing to Holyhead) is known as the A5. Through Milton Keynes, the A5 is diverted onto a new dual carriageway; Watling Street proper remains and forms part of the Milton Keynes grid road system.

The name Watling Street is still used along the ancient road in many places, for instance in Bexleyheath in southeast London and in Canterbury, Gillingham, Strood, Gravesend, and Dartford in Kent. A major road joining the A5 in northwest London is called Watling Avenue. North of London, the name Watling Street still occurs in Hertfordshire (including St Albans), Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire (including Milton Keynes), Northamptonshire (including Towcester), Leicestershire (Hinckley), Warwickshire (including Nuneaton and Atherstone), Staffordshire (including Cannock, Wall, Tamworth and Lichfield), Shropshire (including in Church Stretton along the A49),[16] and even Gwynedd in north Wales.

Other Watling Streets

Dere Street, the Roman road from Cataractonium (Catterick in Yorkshire) to Corstopitum (now Corbridge, Northumberland) to the Antonine Wall, was also sometimes known as Watling Street. A third Watling Street was the Roman road from Mamucium (Manchester) to Bremetennacum (Ribchester) to Cumbria. Preston, Lancashire, preserved a Watling Street Road between Ribbleton and Fulwood, passing the Sharoe Green Hospital.[17] Both of these may preserve a separate derivation from the Old English wealhas ("foreigner") or may have preserved the memory of the long Roman road while misattributing its upper stages to better-preserved roads.

A detail from a 1910 map displaying the Welsh "Watling Street"

A detail from a 1910 map displaying the Welsh "Watling Street" A detail from the same map displaying the Midlands "Watling Street"

A detail from the same map displaying the Midlands "Watling Street" A detail from the same map misattributing Dere Street as "Watling Street"

A detail from the same map misattributing Dere Street as "Watling Street"

See also

Bibliography

- Margary, Ivan (1973), Roman Roads in Britain (3rd ed.), London: John Baker, ISBN 0212970011

- Roucoux, O. (1984), The Roman Watling Street: from London to High Cross, Dunstable Museum Trust, ISBN 0-9508406-2-9.

- John Higgs, (2017). Watling Street: Travels Through Britain and Its Ever-Present Past. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-1-4746-0347-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Watling Street. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Watling Street. |

- The Antonine Itinerary at Roman Britain Online

- "Watling Street – A Journey through Roman Britain" by the BBC

- "Stone Street, Suffolk", at the University of Chicago

References

- 1 2 Williamson, Tom (2000). The Origins of Hertfordshire. Manchester University Press. p. 64. ISBN 071904491X. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ↑ John Cannon, A Dictionary of British History, 2009.

- 1 2 Margary 1973, p. 34.

- ↑ "Loftie's Historic London (review)". The Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art. 63 (1,634): 271. 19 February 1887. Retrieved October 2015. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Ditchfield, Peter Hampson (1901). English Villages. London: Methuen. p. 33.

- 1 2 Wallace, Lacey. The Origin of Roman London. p. 41.

- ↑ Although it is possible the Romans used a ferry prior to the expansion of Londinium in the rebuilding following Boudica's sack of the city in the year 60 or 61.[6]

- ↑ Margary, Ivan D. (1948). Roman Ways in the Weald (third ed.). London: J. M. Dent. p. 126.

- 1 2 3 Itinerarium Antonini Augusti. Hosted at Latin Wikisource. (in Latin)

- 1 2 3 Togodumnus (2011). "The Antonine Itinerary". Roman Britain Online. Retrieved 20 February 2015. (in Latin) & (in English)

- 1 2 "Leges Edwardi Confessoris (ECf1), §12", Early English Laws (in Latin), London: University of London, 2015, retrieved 20 February 2015

- ↑ The other three were "Fosse", "Hikenildestrate" (Icknield Street), and "Herningestrate" (Ermine Street).[11]

- ↑ "House of Lords Journal". British History Online. University of London. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- ↑ Bogart, Dan (2007). "Evidence from Road and River Improvement Authorities, 1600–1750" (PDF). Political Institutions and the Emergence of Regulatory Commitment in England. University of California. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- ↑ Britain's hidden history – London's missing Roman road.

- ↑ Victoria County History - Shropshire A History of the County of Shropshire: Volume 10, Munslow Hundred (Part), the Liberty and Borough of Wenlock, Church Stretton

- ↑ "Bury Metropolitan Council—History"..

Footnotes

- ↑ equivalent to £1,062,218 in 2015 money.