Still life (cellular automaton)

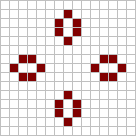

In Conway's Game of Life and other cellular automata, a still life is a pattern that does not change from one generation to the next. A still life can be thought of as an oscillator with unit period.[1]

Pseudo still lifes

A pseudo still life consists of two or more adjacent islands which can be partitioned (either individually or as sets) into non-interacting subparts, which are also still lifes. This compares with a strict still life, in which the islands depend on one another for stability, and thus cannot be decomposed. The distinction between the two is not always obvious, as a strict still life may have multiple connected components all of which are needed for its stability. However, it is possible to determine whether a still life pattern is a strict still life or a pseudo still life in polynomial time by searching for cycles in an associated skew-symmetric graph.[2]

|

|

In Conway's Game of Life

There are many naturally occurring still lifes in Conway's Game of Life. A random initial pattern will leave behind a great deal of debris, containing small oscillators and a large variety of still lifes.

Common examples

Blocks

The most common still life (i.e. that most likely to be generated from a random initial state) is the block.[3] A pair of blocks placed side-by-side (or bi-block) is the simplest pseudo still life. Blocks are used as components in many complex devices, an example being the Gosper glider gun.

| |

|

Hives

The second most common still life is the hive (or beehive).[3] Hives are frequently created in (non-interacting) sets of four, in a formation known as a honey farm.

| |

|

Loaves

The third most common still life is the loaf.[3] Loaves are often found together in a pairing known as a bi-loaf. Bi-loaves themselves are often created in a further (non-interacting) pairing known as a bakery. Two bakeries can extremely rarely form next to each other, forming a set of four loaves known as a tetraloaf alongside two more bi-loafs.

| |

|

|

Tubs, barges, boats and ships

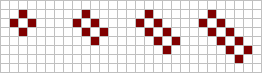

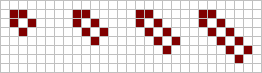

A tub consists of four live cells placed in a diamond shape around a central dead cell. Placing an extra live cell diagonally to the central cell gives another still life, known as a boat. Placing a further live cell on the opposite side gives yet another still life, known as a ship. A tub, a boat or a ship can be extended by adding a pair of live cells, to give a barge, a long-boat or a long-ship respectively. This extension can be repeated indefinitely, to give arbitrarily large structures.

|

|

|

A pair of boats can be combined to give another still life known as the boat tie (a pun on bow tie, which it superficially resembles). Similarly, a pair of ships can be combined into a ship tie.

|

|

Miscellaneous

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eaters and reflectors

Still lifes can be used to modify or destroy other objects. An eater is capable of absorbing a spaceship and returning to its original state after the collision. Many examples exist, with the most notable being the fish-hook (Also known as eater 1), which is capable of absorbing several types of spaceship. A similar device is the reflector, which alters the direction of an incoming spaceship. Eaters and reflectors are not necessarily still lifes, as the term may also apply to oscillators with similar properties.

|

|

Number of different patterns

The number of still lifes existing for a given number of live cells has been documented up to a value of 24 (sequence A019473 in the OEIS).[4][5]

| Live cells | Number of still lifes | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | |

| 2 | 0 | |

| 3 | 0 | |

| 4 | 2 | Block, Tub |

| 5 | 1 | Boat |

| 6 | 5 | Barge, Carrier, Hive, Ship, Snake |

| 7 | 4 | Fish-hook, Loaf, Long boat, Python |

| 8 | 9 | Canoe, Mango, Long barge, Pond |

| 9 | 10 | Integral sign |

| 10 | 25 | Boat tie |

| 11 | 46 | |

| 12 | 121 | Ship tie |

| 13 | 240 | |

| 14 | 619 | Bi-loaf |

| 15 | 1353 | |

| 16 | 3286 | |

| 17 | 7773 | |

| 18 | 19044 | |

| 19 | 45759 | Eater2 |

| 20 | 112243 | |

| 21 | 273188 | |

| 22 | 672172 | |

| 23 | 1646147 | |

| 24 | 4051711 |

Maximum density

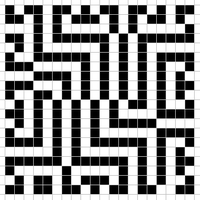

The problem of fitting an n×n region with a maximally dense still life has attracted attention as a test case for constraint programming.[6][7][8][9][10] In the limit of an infinitely large grid, no more than half of the cells in the plane can be live.[11] For finite square grids, greater densities can be achieved. For instance, the maximum density still life within an 8×8 square is a regular grid of nine blocks, with density 36/64 = 0.5625.[6] Optimal solutions are known for squares of all sizes.[12] Yorke-Smith provides a listing of known finite maximum-density patterns.[13]

A 19x19 maximum-density still life in Conway's game of life. |

A 20x20 maximum-density still life in Conway's game of life. |

References

- ↑ "Still Life - from Eric Weisstein's Treasure Trove of Life C.A.". Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- ↑ Cook, Matthew (2003). "Still life theory". New Constructions in Cellular Automata. Santa Fe Institute Studies in the Sciences of Complexity, Oxford University Press. pp. 93–118.

- 1 2 3 Achim Flammenkamp. "Top 100 of Game-of-Life Ash Objects". Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ↑ Niemiec, Mark D. "Life Still-Lifes". Archived from the original on January 21, 2013.

- ↑ Number of stable n-celled patterns ("still lifes") in Conway's game of Life (sequence A019473 in the OEIS).

- 1 2 Bosch, R. A. (1999). "Integer programming and Conway’s game of Life". SIAM Review. 41 (3): 594–604. doi:10.1137/S0036144598338252..

- ↑ Bosch, R. A. (2000). "Maximum density stable patterns in variants of Conway’s game of Life". Operations Research Letters. 27 (1): 7–11. doi:10.1016/S0167-6377(00)00016-X..

- ↑ Smith, Barbara M. (2002). "A dual graph translation of a problem in ‘Life’". Principles and Practice of Constraint Programming - CP 2002. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2470. Springer-Verlag. pp. 89–94. doi:10.1007/3-540-46135-3_27..

- ↑ Bosch, Robert; Trick, Michael (2004). "Constraint programming and hybrid formulations for three Life designs". Annals of Operations Research. 130 (1–4): 41–56. doi:10.1023/B:ANOR.0000032569.86938.2f..

- ↑ Cheng, Kenil C. K.; Yap, Roland H. C. (2006). "Applying ad-hoc global constraints with the case constraint to still-life". Constraints. 11 (2–3): 91–114. doi:10.1007/s10601-006-8058-9..

- ↑ Elkies, Noam D. (1998). "The still life density problem and its generalizations". Voronoi's Impact on Modern Science, Book I. Proc. Inst. Math. Nat. Acad. Sci. Ukraine, vol. 21. pp. 228–253. arXiv:math.CO/9905194

.

. - ↑ Chu, Geoffrey; Stuckey, Peter J. (2012-06-01). "A complete solution to the Maximum Density Still Life Problem". Artificial Intelligence. 184–185: 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.artint.2012.02.001.

- ↑ Neil Yorke-Smith. "Maximum Density Still Life". Artificial Intelligence Center. SRI International.