Hindu temple architecture

The Hindu temple architecture is an open, symmetry driven structure, with many variations, on a square grid of padas, depicting perfect geometric shapes such as circles and squares.[2][3]

In ancient Indian texts, a temple is a place for Tirtha - pilgrimage.[4] It is a sacred site whose ambience and design attempts to symbolically condense the ideal tenets of Hindu way of life.[3] All the cosmic elements that create and celebrate life in Hindu pantheon, are present in a Hindu temple - from fire to water, from images of nature to deities, from the feminine to the masculine, from kama to artha, from the fleeting sounds and incense smells to Purusha - the eternal nothingness yet universality - is part of a Hindu temple architecture.[4]

The architectural principles of Hindu temples in India are described in Shilpa Shastras and Vastu Sastras.[5][6] The Hindu culture has encouraged aesthetic independence to its temple builders, and its architects have sometimes exercised considerable flexibility in creative expression by adopting other perfect geometries and mathematical principles in Mandir construction to express the Hindu way of life.[2]

Design

Susan Lewandowski states[7] that the underlying principle in a Hindu temple is built around the belief that all things are one, everything is connected. The pilgrim is welcomed through mathematically structured spaces, a network of art, pillars with carvings and statues that display and celebrate the four important and necessary principles of human life - the pursuit of artha (prosperity, wealth), the pursuit of kama (desire), the pursuit of dharma (virtues, ethical life) and the pursuit of moksha (release, self-knowledge).[8][9]

At the center of the temple, typically below and sometimes above or next to the deity, is mere hollow space with no decoration, symbolically representing Purusa, the Supreme Principle, the sacred Universal, one without form, which is present everywhere, connects everything, and is the essence of everyone. A Hindu temple is meant to encourage reflection, facilitate purification of one’s mind, and trigger the process of inner realization within the devotee.[4] The specific process is left to the devotee’s school of belief. The primary deity of different Hindu temples varies to reflect this spiritual spectrum.

The site

The appropriate site for a Mandir, suggest ancient Sanskrit texts, is near water and gardens, where lotus and flowers bloom, where swans, ducks and other birds are heard, where animals rest without fear of injury or harm.[4] These harmonious places were recommended in these texts with the explanation that such are the places where gods play, and thus the best site for Hindu temples.[4][7]

While major Hindu Mandirs are recommended at sangams (confluence of rivers), river banks, lakes and seashore, Brhat Samhita and Puranas suggest temples may also be built where a natural source of water is not present. Here too, they recommend that a pond be built preferably in front or to the left of the temple with water gardens. If water is neither present naturally nor by design, water is symbolically present at the consecration of temple or the deity. Temples may also be built, suggests Visnudharmottara in Part III of Chapter 93,[10] inside caves and carved stones, on hill tops affording peaceful views, mountain slopes overlooking beautiful valleys, inside forests and hermitages, next to gardens, or at the head of a town street.

The layout

A Hindu temple design follows a geometrical design called vastu-purusha-mandala. The name is a composite Sanskrit word with three of the most important components of the plan. Mandala means circle, Purusha is universal essence at the core of Hindu tradition, while Vastu means the dwelling structure.[11] Vastupurushamandala is a yantra.[12] The design lays out a Hindu temple in a symmetrical, self-repeating structure derived from central beliefs, myths, cardinality and mathematical principles.[2]

The four cardinal directions help create the axis of a Hindu temple, around which is formed a perfect square in the space available. The circle of mandala circumscribes the square. The square is considered divine for its perfection and as a symbolic product of knowledge and human thought, while circle is considered earthly, human and observed in everyday life (moon, sun, horizon, water drop, rainbow). Each supports the other.[4] The square is divided into perfect square grids. In large temples, this is often a 8x8 or 64 grid structure. In ceremonial temple superstructures, this is an 81 sub-square grid. The squares are called ‘‘padas’’.[2][13] The square is symbolic and has Vedic origins from fire altar, Agni. The alignment along cardinal direction, similarly is an extension of Vedic rituals of three fires. This symbolism is also found among Greek and other ancient civilizations, through the gnomon. In Hindu temple manuals, design plans are described with 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81 up to 1024 squares; 1 pada is considered the simplest plan, as a seat for a hermit or devotee to sit and meditate on, do yoga, or make offerings with Vedic fire in front. The second design of 4 padas has a symbolic central core at the diagonal intersection, and is also a meditative layout. The 9 pada design has a sacred surrounded center, and is the template for the smallest temple. Older Hindu temple vastumandalas may use the 9 through 49 pada series, but 64 is considered the most sacred geometric grid in Hindu temples. It is also called Manduka, Bhekapada or Ajira in various ancient Sanskrit texts. Each pada is conceptually assigned to a symbolic element, sometimes in the form of a deity or to a spirit or apasara. The central square(s) of the 64 is dedicated to the Brahman (not to be confused with Brahmin), and are called Brahma padas.

In a Hindu temple’s structure of symmetry and concentric squares, each concentric layer has significance. The outermost layer, Paisachika padas, signify aspects of Asuras and evil; the next inner concentric layer is Manusha padas signifying human life; while Devika padas signify aspects of Devas and good. The Manusha padas typically houses the ambulatory.[4] The devotees, as they walk around in clockwise fashion through this ambulatory to complete Parikrama (or Pradakshina), walk between good on inner side and evil on the outer side. In smaller temples, the Paisachika pada is not part of the temple superstructure, but may be on the boundary of the temple or just symbolically represented.

The Paisachika padas, Manusha padas and Devika padas surround Brahma padas, which signifies creative energy and serves as the location for temple’s primary idol for darsana. Finally at the very center of Brahma padas is Garbhagruha(Garbha- Centre, gruha- house; literally the center of the house) (Purusa Space), signifying Universal Principle present in everything and everyone.[4] The spire of a Hindu temple, called Shikhara in north India and Vimana in south India, is perfectly aligned above the Brahma pada(s).

Beneath the mandala's central square(s) is the space for the formless shapeless all pervasive all connecting Universal Spirit, the Purusha. This space is sometimes referred to as garbha-griya (literally womb house) - a small, perfect square, windowless, enclosed space without ornamentation that represents universal essence.[11] In or near this space is typically a murti (idol). This is the main deity idol, and this varies with each temple. Often it is this idol that gives it a local name, such as Visnu temple, Krishna temple, Rama temple, Narayana temple, Siva temple, Lakshmi temple, Ganesha temple, Durga temple, Hanuman temple, Surya temple, and others.[3] It is this garbha-griya which devotees seek for ‘‘darsana’’ (literally, a sight of knowledge,[15] or vision[11]).

Above the vastu-purusha-mandala is a superstructure with a dome called Shikhara in north India, and Vimana in south India, that stretches towards the sky.[11] Sometimes, in makeshift temples, the dome may be replaced with symbolic bamboo with few leaves at the top. The vertical dimension's cupola or dome is designed as a pyramid, conical or other mountain-like shape, once again using principle of concentric circles and squares (see below).[4] Scholars suggest that this shape is inspired by cosmic mountain of Meru or Himalayan Kailasa, the abode of gods according to Vedic mythology.[11]

In larger temples, the outer three padas are visually decorated with carvings, paintings or images meant to inspire the devotee.[4] In some temples, these images or wall reliefs may be stories from Hindu Epics, in others they may be Vedic tales about right and wrong or virtues and vice, in some they may be idols of minor or regional deities. The pillars, walls and ceilings typically also have highly ornate carvings or images of the four just and necessary pursuits of life - kama, artha, dharma and moksa. This walk around is called pradakshina.[11]

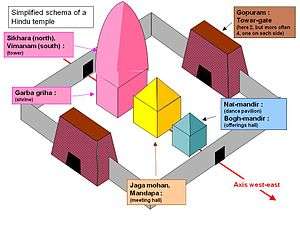

Large temples also have pillared halls called mandapa. One on the east side, serves as the waiting room for pilgrims and devotees. The mandapa may be a separate structure in older temples, but in newer temples this space is integrated into the temple superstructure. Mega temple sites have a main temple surrounded by smaller temples and shrines, but these are still arranged by principles of symmetry, grids and mathematical precision. An important principle found in the layout of Hindu temples is mirroring and repeating fractal-like design structure,[16] each unique yet also repeating the central common principle, one which Susan Lewandowski refers to as “an organism of repeating cells”.[17]

- Exceptions to the square grid principle

Predominant number of Hindu temples exhibit the perfect square grid principle.[18] However, there are some exceptions. For example, the Teli-ka-mandir in Gwalior, built in the 8th century CE is not a square but is a rectangle in 2:3 proportion. Further, the temple explores a number of structures and shrines in 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, 2:5, 3:5 and 4:5 ratios. These ratios are exact, suggesting the architect intended to use these harmonic ratios, and the rectangle pattern was not a mistake, nor an arbitrary approximation. Other examples of non-square harmonic ratios are found at Naresar temple site of Madhya Pradesh and Nakti-Mata temple near Jaipur, Rajasthan. Michael Meister suggests that these exceptions mean the ancient Sanskrit manuals for temple building were guidelines, and Hinduism permitted its artisans flexibility in expression and aesthetic independence.[2]

Different styles of architecture

Nagara architecture

Nagara temples have two distinct features :

- In plan, the temple is a square with a number of graduated projections in the middle of each side giving a cruciform shape with a number of re-entrant angles on each side.

- In elevation, a Shikhara, i.e., tower gradually inclines inwards in a convex curve, using a concentric rotating-squares and circles principle.

Temples built between the 7th and the 14th centuries CE in the nagara style had mandapas (pavilions)

The projections in the plan are also carried upwards to the top of the Shikhara and, thus, there is strong emphasis on vertical lines in elevation. The Nagara style is widely distributed over a greater part of India, exhibiting distinct varieties and ramifications in lines of evolution and elaboration according to each locality. An example of Nagara architecture is the Kandariya Mahadeva Temple.

Dravidian architecture (South India)

Dravidian style temples consist almost invariably of the four following parts, differing only according to the age in which they were executed:[19]

- The principle part, the temple itself, is called the Vimana (or vimana). It is always square in plan and surmounted by a pyramidal roof of one or more stories; it contains the cell where the image of the god or his emblem is placed.

- The porches or Mandapas (or Mantapams), which always cover and precede the door leading to the cell.

- Gate-pyramids, Gopurams, which are the principal features in the quadrangular enclosures that surround the more notable temples.

- Pillared halls or Chaultris—properly Chawadis -- used for various purposes, and which are the invariable accompaniments of these temples.

Besides these, a temple always contains temple tanks or wells for water (used for sacred purposes or the convenience of the priests), dwellings for all grades of the priesthood are attached to it, and other buildings for state or convenience.[19]

Badami Chalukya architecture

The Badami Chalukya Architecture|Chalukya style originated during 450 CE in Aihole and perfected in Pattadakal and Badami.[20]

The period of Badami Chalukyas was a glorious era in the history of Indian architecture. The capital of the Chalukyas, Vatapi (Badami, in Bagalkot district, in Karnataka) is situated at the mouth of a ravine between two rocky hills. Between 500 and 757 CE, Badami Chalukyas established the foundations of cave temple architecture, on the banks of the Malaprabha River. Those styles mainly include Aihole, Pattadakal and Badami. The sites were built out of sandstone cut into enormous blocks from the outcrops in the chains of the Kaladgi hills.

At Badami, Chalukyas carved some of the finest cave temples. Mahakuta, the large trees under which the shrine nestles.

In Aihole, known as the "Cradle of Indian architecture," there are over 150 temples scattered around the village. The Lad Khan Temple is the oldest. The Durga Temple is notable for its semi-circular apse, elevated plinth and the gallery that encircles the sanctum sanctorum. A sculpture of Vishnu sitting atop a large cobra is at Hutchimali Temple. The Ravalphadi cave temple celebrates the many forms of Shiva. Other temples include the Konthi temple complex and the Meguti Jain temple.

Pattadakal is a (World Heritage Site), where one finds the Virupaksha temple; it is the biggest temple, having carved scenes from the great epics of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Other temples at Pattadakal are Mallikarjuna, Kashivishwanatha, Galaganatha and Papanath.

Gadag architecture

The Gadag style of architecture is also called Western Chalukya architecture.[21] The style flourished for 150 years (1050 to 1200 CE); in this period, about 50 temples were built. Some examples are the Saraswati temple in the Trikuteshwara temple complex at Gadag, the Doddabasappa Temple at Dambal, the Kasivisvesvara Temple at Lakkundi, and the Amriteshwara temple at Annigeri. which is marked by ornate pillars with intricate sculpture.[22] This style originated during the period of the Kalyani Chalukyas (also known as Western Chalukya) Someswara I.

- Gadag/Western Chalukya style Architecture of temples

Stepped floorplan of Dattatreya Temple (one side of the shrine) with five projections at Chattarki in Gulbarga district, 12th century CE

Stepped floorplan of Dattatreya Temple (one side of the shrine) with five projections at Chattarki in Gulbarga district, 12th century CE Shrine wall and superstructure in Kasivisvesvara temple at Lakkundi

Shrine wall and superstructure in Kasivisvesvara temple at Lakkundi- Ornate Gadag style pillars at Sarasvati Temple, Trikuteshwara temple complex at Gadag

- Mahadeva Temple at Itagi, Koppal district in Karnataka, also called Devalaya Chakravarti,[23][24][25] 1112 CE, an example of dravida articulation with a nagara superstructure.

Kalinga architecture

The design which flourished in eastern Indian state of Odisha and Northern Andhra Pradesh are called Kalinga style of architecture. The style consists of three distinct type of temples namely Rekha Deula, Pidha Deula and Khakhara Deula. Deula means "temple" in the local language. The former two are associated with Vishnu, Surya and Shiva temple while the third is mainly with Chamunda and Durga temples. The Rekha deula and Khakhara deula houses the sanctum sanctorum while the Pidha Deula constitutes outer dancing and offering halls.

The prominent examples of Rekha Deula are Lingaraj Temple of Bhubaneswar and Jagannath Temple of Puri. One of the prominent example of Khakhara Deula is Vaital Deula. The Konark Sun Temple is a living example of Pidha Deula.

Māru-Gurjara temple architecture

Māru-Gurjara temple architecture originated somewhere in the 6th century in and around areas of Rajasthan. Māru-Gurjara architecture show the deep understanding of structures and refined skills of Rajasthani craftmen of bygone era. Māru-Gurjara architecture has two prominent styles: Maha-Maru and Maru-Gurjara. According to Madhusudan Dhaky, Maha-Maru style developed primarily in Marudesa, Sapadalaksha, Surasena and parts of Uparamala whereas Maru-Gurjara originated in Medapata, Gurjaradesa-Arbuda, Gurjaradesa-Anarta and some areas of Gujarat.[26] Scholars such as George Michell, Dhaky, Michael W. Meister and U.S. Moorti believe that Māru-Gurjara temple architecture is entirely Western Indian architecture and is quite different from the North Indian temple architecture.[27]

This further shows the cultural and ethnic separation of Rajasthanis from north Indian culture. There is a connecting link between Māru-Gurjara architecture and Hoysala temple architecture. In both of these styles architecture is treated sculpturally.[28]

Indonesian architecture

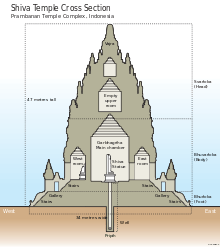

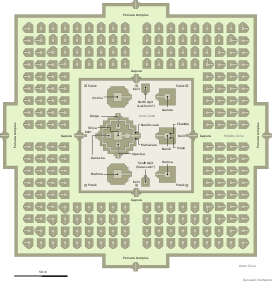

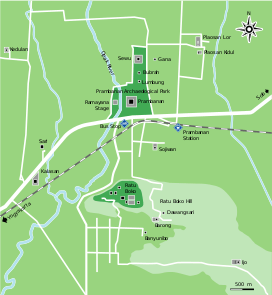

A candi (pronounced [tʃandi]) is a Hindu or Buddhist temple in Indonesia, it refers to a structure based on the Indian type of single-celled shrine, with a pyramidal tower above it, and a portico for entrance,[29] mostly built during the Indianized period, between the 7th to 15th centuries.[30][31] In Hindu Balinese architecture, a candi shrine can be found within a pura compound. The best example of Indonesian Javanese Hindu temple architecture is the 9th century Prambanan (Shivagrha) temple compound, located in Central Java, near Yogyakarta. This largest Hindu temple in Indonesia has three main prasad towers, dedicated to Trimurti gods. Shiva temple, the largest main temple is towering to 47 metre-high (154 ft).

The term "candi" itself is believed was derived from Candika, one of the manifestations of the goddess Durga as the goddess of death.[32] This suggests that in ancient Indonesia the "candi" had mortuary functions as well as connections with the afterlife. Historians suggest that the temples of ancient Java were also used to store the ashes of cremated deceased kings. The statue of god stored inside the garbhagriha of the temple is often modeled after the deceased king and considered to be the deified person of the king portrayed as Vishnu or Shiva according to the concept of devaraja. The example is the statue of king Airlangga from Belahan temple portrayed as Vishnu riding Garuda.

The candi architecture follows the typical Hindu architecture traditions based on Vastu Shastra. The temple layout, especially in central Java period, incorporated mandala temple plan arrangements and also the typical high towering spires of Hindu temples. The candi was designed to mimic Meru, the holy mountain the abode of gods. The whole temple is a model of Hindu universe according to Hindu cosmology and the layers of Loka.[33]

The candi structure and layout recognize the hierarchy of the zones, spanned from the less holy to the holiest realms. The Indic tradition of Hindu-Buddhist architecture recognize the concept of arranging elements in three parts or three elements. Subsequently, the design, plan and layout of the temple follows the rule of space allocation within three elements; commonly identified as foot (base), body (center), and head (roof). They are Bhurloka represented by the outer courtyard and the foot (base) part of each temples, Bhuvarloka represented by the middle courtyard and the body of each temples, and Svarloka which symbolized by the roof of Hindu structure usually crowned with ratna (sanskrit: jewel) or vajra.

Khmer architecture

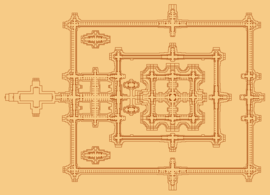

Between the 9th and the 14th century, the Khmer Empire flourished in present-day Cambodia with its influence extended to most of mainland Southeast Asia. Its great capital, Angkor (Khmer: អង្គរ, "Capital City", derived from Sanskrit "nagara"), contains some of the most important and the most magnificent example of Khmer temple architecture. The classic style of Angkorian temple is demonstrated by the 12th century Angkor Wat. Angkorian builders mainly used sandstone and laterite as temple building materials.

The main super structure of typical Khmer temple is a towering prasat called prang which houses the garbhagriha inner chamber, where the murti of Vishnu or Shiva, or a lingam resides. Khmer temples were typically enclosed by a concentric series of walls, with the central sanctuary in the middle; this arrangement represented the mountain ranges surrounding Mount Meru, the mythical home of the gods. Enclosures are the spaces between these walls, and between the innermost wall and the temple itself. The walls defining the enclosures of Khmer temples are frequently lined by galleries, while passage through the walls is by way of gopuras located at the cardinal points. The main entrance usually adorned with elevated causeway with cruciform terrace.[34]

Champa architecture

Between the 6th and the 16th century, the Kingdom of Champa flourished in present-day central and southern Vietnam. Unlike the Javanese that mostly used volcanic andesite stone for their temples, and Khmer of Angkor which mostly employed grey sandstones to construct their religious buildings, the Cham built their temples from reddish bricks. The most important remaining sites of Cham bricks temple architecture include Mỹ Sơn near Da Nang, Po Nagar near Nha Trang, and Po Klong Garai near Phan Rang.

Typically, a Cham temple complex consisted of several different kinds of buildings.[35] They are kalan, a brick sanctuary, typically in the form of a tower with garbahgriha used to host the murti of deity. A mandapa is an entry hallway connected with a sanctuary. A kosagrha or "fire-house" is a temple construction typically with a saddle-shaped roof, used to house the valuables belonging to the deity or to cook for the deity. The gopura was a gate-tower leading into a walled temple complex. These building types are typical for Hindu temples in general; the classification is valid not only for the architecture of Champa, but also for other architectural traditions of Greater India.

Chronology

The Magadha empire rose with the Shishunaga dynasty in around 650 BCE. The Ashtadhyayi of Panini, a grammarian of the 5th century BCE speaks of images that were used in Hindu temple worship. The ordinary images were called pratikriti and the images for worship were called archa (see As. 5.3.96–100). Patanjali, the 2nd-century BCE author of the Mahabhashya commentary on the Ashtadhyayi, tells us more about the images.

Deity images for sale were called Shivaka etc., but an archa of Shiva was just called Shiva. Patanjali mentions Shiva and Skanda deities. There is also mention of the worship of Vasudeva (Krishna). We are also told that some images could be moved and some were immoveable. Panini also says that an archa was not to be sold and that there were people (priests) who obtained their livelihood by taking care of it.

Panini and Patanjali mention temples which were called prasadas.

The earlier Shatapatha Brahmana of the period of the Vedas, informs us of an image in the shape of Purusha which was placed within the altar. The Vedic books describe the plan of the temple to be square. This plan is divided into 64 or 81 smaller squares, where each of these represent a specific divinity.

Historical chronology

Early temples in approximate chronological order:[36]

- Gupta period temples (320 - 550 CE) at Sanchi, Tigawa, Eran, Bhumra, Nachna

- Deogarh, Lalitpur District, 500-525 CE

- Bhitargaon, Kanpur Nagar District, Brick temple, 6th century

- Mahabodhi Temple, Bodh Gaya, 234 BC onwards

- Lakshman Brick Temple, Sirpur 600-625 CE

- Parsurameswar Temple, Bhubaneshwar 600-650 CE

- Mahabalipuram 650-675 CE

- Rajiv Lochan temple, Rajim, 600 CE[37]

- Aihole Meguti Temple 634 CE, Lad Khan and Durga Temples, 7th century

- Alampur Garuda-brahma 696-734 CE, Svarga brahma 681-696 CE, Visva-Brahma 700 CE

- Badami Chalukya architecture, 400-700 CE, Malegutti, Bhutanath

- Ellora, Kailas 750-775 CE, cave 32, 800-825 CE

- Pattadakal Virupaksh, Mallikarjuna, 745 CE

- Temples at Mahua, Amril, Naresar, Batesar: 8th century

- Osian Surya 700-725 CE, Harihar 775-800 CE

- Gwalior Teli Ka Mandir 725-750 CE

- Vaital Deula, Bhubaneshwar, 750-800 CE

- Madhakheda Madhaya Pradesh, 825 CE

Glossary

In design/plan of a temple, several parts of Temple architecture are considered, most common amongst these are:

Jagati

Jagati is a term used to refer a raised surface, platform or terrace upon which the temple is placed.[38]

Antarala

Antarala is a small antechamber or foyer between the garbhagriha/ garbha graha (shrine) and the mandapa, more typical of north Indian temples.[39][40]

Mandapa

Mandapa (or Mandapam) (मंडप in Hindi/Sanskrit, also spelled mantapa or mandapam) is a term to refer to pillared outdoor hall or pavilion for public rituals.[41]

- Ardha Mandapam — intermediary space between the temple exterior and the garba griha (sanctum sanctorum) or the other mandapas of the temple

- Asthana Mandapam — assembly hall

- Kalyana Mandapam — dedicated to ritual marriage celebration of the Lord with Goddess

- Maha Mandapam — (Maha=big) When there are several mandapas in the temple, it is the biggest and the tallest. It is used for conducting religious discourses.

- Nandi Mandapam (or Nandi mandir) - In the Shiva temples, pavilion with a statue of the sacred bull Nandi, looking at the statue or the lingam of Shiva.

Sreekovil or Garbhagriha

Sreekovil or Garbhagriha the part in which the idol of the deity in a Hindu temple is installed i.e. Sanctum sanctorum. The area around is referred as to the Chuttapalam, which generally includes other deities and the main boundary wall of the temple. Typically there is also a Pradakshina area in the Sreekovil and one outside, where devotees can take Pradakshinas.[40]

Shikhara

Shikhara or vimanam literally means "mountain peak", refer to the rising tower over the sanctum sanctorum where the presiding deity is enshrined is the most prominent and visible part of a Hindu temples.

Amalaka

An amalaka is a stone disk, often with ridges, that sits on a temple's main tower (Shikhara).[40]

Gopuram

Gopuras (or Gopurams) are the elaborate gateway-towers of south Indian temples, not to be confused with Shikharas.

Urushringa

An urushringa is a subsidiary Shikhara, lower and narrower, tied against the main shikhara.[40]

Gallery

Muktesvara deula Panoramic View, Odisha

Muktesvara deula Panoramic View, Odisha Lingaraja Temple Panoramic View, Odisha

Lingaraja Temple Panoramic View, Odisha Rajarani Temple Panoramic View, Odisha

Rajarani Temple Panoramic View, Odisha Harishankar Temple Panoramic View, Odisha

Harishankar Temple Panoramic View, Odisha Manikeshwari Temple Panoramic View, Odisha

Manikeshwari Temple Panoramic View, Odisha

The Kalayar Kovilat Sivganga.

The Kalayar Kovilat Sivganga. Mandasa Basudeva Temple, Andhra Pradesh

Mandasa Basudeva Temple, Andhra Pradesh Vadakkunnathan Temple, Thrissur, Kerala

Vadakkunnathan Temple, Thrissur, Kerala Madurai Meenakshi Temple, Tamil Nadu

Madurai Meenakshi Temple, Tamil Nadu

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Temple architecture of India. |

- Vastu Shastra

- Shilpa Shastras

- Temple tank

- Vedic altars

- Indian architecture

- Hoysala architecture

- Western Chalukya architecture / Gadag Style of architecture

- Chola art

- Indonesian architecture, Candi of Indonesia

- Rock-cut architecture

- Indian rock-cut architecture

- Architecture of Angkor

- Hemadpanthi architecture Style

- Dwajasthambam (flagstaff)

References

- ↑ "Angkor Temple Guide". Angkor Temple Guide. 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Meister, Michael (1983). "Geometry and Measure in Indian Temple Plans: Rectangular Temples". Artibus Asiae. 44 (4): 266–296. JSTOR 3249613. doi:10.2307/3249613.

- 1 2 3 George Michell (1988), The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to Its Meaning and Forms, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226532301, Chapter 1

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, Vol 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0222-3

- ↑ Jack Hebner (2010), Architecture of the Vastu Sastra - According to Sacred Science, in Science of the Sacred (Editor: David Osborn), ISBN 978-0557277247, pp 85-92; N Lahiri (1996), Archaeological landscapes and textual images: a study of the sacred geography of late medieval Ballabgarh, World Archaeology, 28(2), pp 244-264

- ↑ BB Dutt (1925), Town planning in Ancient India at Google Books, ISBN 978-81-8205-487-5

- 1 2 Susan Lewandowski, The Hindu Temple in South India, in Buildings and Society: Essays on the Social Development of the Built Environment, Anthony D. King (Editor), ISBN 978-0710202345, Routledge, Chapter 4

- ↑ Alain Daniélou (2001), The Hindu Temple: Deification of Eroticism, Translated from French to English by Ken Hurry, ISBN 0-89281-854-9, pp 101-127

- ↑ Samuel Parker (2010), Ritual as a Mode of Production: Ethnoarchaeology and Creative Practice in Hindu Temple Arts, South Asian Studies, 26(1), pp 31-57; Michael Rabe, Secret Yantras and Erotic Display for Hindu Temples, (Editor: David White), ISBN 978-8120817784, Princeton University Readings in Religion (Motilal Banarsidass Publishers), Chapter 25, pp 435-446

- ↑ Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, Vol 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0222-3, page 5-6

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Susan Lewandowski, The Hindu Temple in South India, in Buildings and Society: Essays on the Social Development of the Built Environment, Anthony D. King (Editor), ISBN 978-0710202345, Routledge, pp 68-69

- ↑ Stella Kramrisch (1976), The Hindu Temple Volume 1 & 2, ISBN 81-208-0223-3

- ↑ In addition to square (4) sided layout, Brhat Samhita also describes Vastu and mandala design principles based on a perfect triangle (3), hexagon (6), octagon (8) and hexadecagon (16) sided layouts, according to Stella Kramrisch. The 49 grid design is called Sthandila and of great importance in creative expressions of Hindu temples in South India, particularly in ‘‘Prakaras’’.

- ↑ Meister, Michael W. (March 2006). "Mountain Temples and Temple-Mountains: Masrur". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 65 (1): 26–49. JSTOR 25068237. doi:10.2307/25068237.

- ↑ Stella Kramrisch (1976), The Hindu Temple Volume 1, ISBN 81-208-0223-3, pp 8

- ↑ Trivedi, K. (1989). Hindu temples: models of a fractal universe. The Visual Computer, 5(4), 243-258

- ↑ Susan Lewandowski, The Hindu Temple in South India, in Buildings and Society: Essays on the Social Development of the Built Environment, Anthony D. King (Editor), ISBN 978-0710202345, Routledge, pp 71-73

- ↑ Meister, Michael W. (April–June 1979). "Maṇḍala and Practice in Nāgara Architecture in North India". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 99 (2): 204–219. JSTOR 602657. doi:10.2307/602657.

- 1 2 Fergusson, James (1997) [1910]. History of Indian and Eastern Architecture (3rd ed.). mumbai: Low Price Publications. p. 408.

- ↑ "Echoes from Chalukya caves". Retrieved 2009-04-01.

- ↑ "In search of Indian records of Supernovae1" (PDF). Hrishikesh Jogleka1, Aniket Sule, M N Vahia. Retrieved 2009-04-03.

- ↑ "Kalyani Chalukyan temples, Temples of Karnataka". Retrieved 2009-04-03.

- ↑ Cousens (1926), p. 101

- ↑ Kamath (2001), pp. 117–118

- ↑ Rao, Kishan. "Emperor of Temples crying for attention". The Hindu, June 10, 2002. The Hindu. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- ↑ The sculpture of early medieval Rajasthan, by Cynthia Packert Atherton

- ↑ Beginnings of Medieval Idiom c. A.D. 900–1000 by George Michell

- ↑ The legacy of G.S. Ghurye: a centennial festschrift, by Govind Sadashiv Ghurye, A. R. Momin, p. 205

- ↑ Philip Rawson: The Art of Southeast Asia

- ↑ Philip Rawson: The Art of Southeast Asia

- ↑ Soekmono (1995), p. 1

- ↑ Soekmono, Dr R. (1973). Pengantar Sejarah Kebudayaan Indonesia 2. Yogyakarta, Indonesia: Penerbit Kanisius. p. 81. ISBN 979-413-290-X.

- ↑ Sedyawati (2013), p. 4

- ↑ Glaize, Monuments of the Angkor Group, p.27.

- ↑ Tran Ky Phuong, Vestiges of Champa Civilization.

- ↑ Meister, Michael W. (1988–1989). "Prāsāda as Palace: Kūṭina Origins of the Nāgara Temple". Artibus Asiae. 49 (3–4): 254–280. JSTOR 3250039. doi:10.2307/3250039.

- ↑

- ↑ "Glossary". Art and Archaeology. Retrieved 2007-04-09.

- ↑ cite web |url=http://www.indoarch.org/arch_glossary.php |title=Architecture on the Indian Subcontinent - Glossary |publisher= |accessdate=2007-01-26

- 1 2 3 4 http://personal.carthage.edu/jlochtefeld/picturepages/Khajuraho/architecture.html

- ↑ Thapar, Binda (2004). Introduction to Indian Architecture. Singapore: Periplus Editions. p. 143. ISBN 0-7946-0011-5.

Further reading

- Vastu-Silpa Kosha, Encyclopedia of Hindu Temple architecture and Vastu/S.K. Ramachandara Rao, Delhi, Devine Books, (Lala Murari Lal Chharia Oriental series) ISBN 978-93-81218-51-8 (Set)

- Dehejia, V. (1997). Indian Art. Phaidon: London. ISBN 0-7148-3496-3.

- Acharya, Prasanna Kumar (1946). An encyclopaedia of Hindu architecture. Oxford University Press.

- Hardy, Adam (2007). The Temple Architecture of India, Wiley: Chichester. ISBN 978-0-470-02827-8

- Mitchell, George (1988). The Hindu Temple, University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL. ISBN 0-226-53230-5

- Rajan, K.V. Soundara (1998). Rock-Cut Temple Styles. Somaiya Publications: Mumbai. ISBN 81-7039-218-7

.jpg)