Steam locomotive

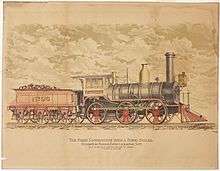

A steam locomotive is a type of railway locomotive that produces its pulling power through a steam engine. These locomotives are fueled by burning combustible material – usually coal, wood, or oil – to produce steam in a boiler. The steam moves reciprocating pistons which are mechanically connected to the locomotive's main wheels (drivers). Both fuel and water supplies are carried with the locomotive, either on the locomotive itself or in wagons (tenders) pulled behind. The first steam locomotive, made by Richard Trevithick, first operated on 21 February 1804, three years after the road locomotive he made in 1801. The first practical steam locomotive was created in 1812–13 by John Blenkinsop.[1] Built by George Stephenson and his son Robert's company Robert Stephenson and Company, the Locomotion No. 1 is the first steam locomotive to carry passengers on a public rail line, the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1825.

Steam locomotives were first developed in Great Britain during the early 19th century and used for railway transport until the middle of the 20th century. From the early 1900s they were gradually superseded by electric and diesel locomotives, with full conversion to electric and diesel power beginning in the late 1930s. The majority of steam locomotives were retired from regular service by the 1980s, though several continue to run on tourist and heritage lines.

Origins

United Kingdom

The earliest railways employed horses to draw carts along railway tracks.[2] In 1784, William Murdoch, a Scottish inventor, built a small-scale prototype of a steam road locomotive.[3] A full-scale rail steam locomotive was proposed by William Reynolds around 1787.[4] An early working model of a steam rail locomotive was designed and constructed by steamboat pioneer John Fitch in the US during 1794.[5] His steam locomotive used interior bladed wheels guided by rails or tracks. The model still exists at the Ohio Historical Society Museum in Columbus.[6] The authenticity and date of this locomotive is disputed by some experts and a workable steam train would have to await the invention of the high-pressure steam engine by Richard Trevithick, who pioneered the use of steam locomotives.[7]

The first full-scale working railway steam locomotive, was the 3 ft (914 mm) gauge Coalbrookdale Locomotive, built by Trevithick in 1802. It was constructed for the Coalbrookdale ironworks in Shropshire in the United Kingdom though no record of it working there has survived.[8] On 21 February 1804, the first recorded steam-hauled railway journey took place as another of Trevithick's locomotives hauled a train along the 4 ft 4 in (1,321 mm) tramway from the Pen-y-darren ironworks, near Merthyr Tydfil, to Abercynon in South Wales.[9][10] Accompanied by Andrew Vivian, it ran with mixed success.[11] The design incorporated a number of important innovations that included using high-pressure steam which reduced the weight of the engine and increased its efficiency.

Trevithick visited the Newcastle area in 1804 and had a ready audience of colliery (coal mine) owners and engineers. The visit was so successful that the colliery railways in north-east England became the leading centre for experimentation and development of the steam locomotive.[12] Trevithick continued his own steam propulsion experiments through another trio of locomotives, concluding with the Catch Me Who Can in 1808.

In 1812, Matthew Murray's successful twin-cylinder rack locomotive Salamanca first ran on the edge-railed rack-and-pinion Middleton Railway.[13] Another well-known early locomotive was Puffing Billy, built 1813–14 by engineer William Hedley. It was intended to work on the Wylam Colliery near Newcastle upon Tyne. This locomotive is the oldest preserved, and is on static display in the Science Museum, London. George Stephenson built Locomotion No. 1 for the Stockton and Darlington Railway, north-east England, which was the first public steam railway in the world. In 1829, his son Robert built in Newcastle The Rocket which was entered in and won the Rainhill Trials. This success led to the company emerging as the pre-eminent builder of steam locomotives used on railways in the UK, US and much of Europe.[14] The Liverpool and Manchester Railway opened a year later making exclusive use of steam power for passenger and goods trains.

United States

Many of the earliest locomotives for American railroads were imported from Great Britain, including first the Stourbridge Lion and later the John Bull (still the oldest operable engine-powered vehicle in the United States of any kind, as of 1981) however a domestic locomotive-manufacturing industry was quickly established. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad's Tom Thumb in 1830, designed and built by Peter Cooper,[15] was the first US-built locomotive to run in America, although it was intended as a demonstration of the potential of steam traction, rather than as a revenue-earning locomotive. The DeWitt Clinton was also built in the 1830s.[14]

The first US patent, US1, was obtained in 1836 by John Ruggles for a Locomotive steam-engine for rail and other roads. Ruggles' proposed locomotive had a two-speed gear and a rack mechanism which was only engaged when climbing steep hills.[16] It is not known whether it was actually built.

Continental Europe

The first railway service outside of the United Kingdom and North America was opened on 5 May 1835 in Belgium, between Mechelen and Brussels. The locomotive was named The Elephant.

In Germany, the first working steam locomotive was a rack-and-pinion engine, similar to the Salamanca, designed by the British locomotive pioneer John Blenkinsop. Built in June 1816 by Johann Friedrich Krigar in the Royal Berlin Iron Foundry (Königliche Eisengießerei zu Berlin), the locomotive ran on a circular track in the factory yard. It was the first locomotive to be built on the European mainland and the first steam-powered passenger service; curious onlookers could ride in the attached coaches for a fee. It is portrayed on a New Year's badge for the Royal Foundry dated 1816. Another locomotive was built using the same system in 1817. They were to be used on pit railways in Königshütte and in Luisenthal on the Saar (today part of Völklingen), but neither could be returned to working order after being dismantled, moved and reassembled. On 7 December 1835 the Adler ran for the first time between Nuremberg and Fürth on the Bavarian Ludwig Railway. It was the 118th engine from the locomotive works of Robert Stephenson and stood under patent protection.

In 1837, the first steam railway started in Austria on the Emperor Ferdinand Northern Railway between Vienna-Floridsdorf and Deutsch-Wagram. The oldest continually working steam engine in the world also runs in Austria: the GKB 671 built in 1860, has never been taken out of service, and is still used for special excursions.

In 1838, the third steam locomotive to be built in Germany, the Saxonia, was manufactured by the Maschinenbaufirma Übigau near Dresden, built by Prof. Johann Andreas Schubert. The first independently designed locomotive in Germany was the Beuth, built by August Borsig in 1841. The first locomotive produced by Henschel-Werke in Kassel, the Drache, was delivered in 1848.

The first steam locomotives operating in Italy were the Bayard and the Vesuvio, running on the Napoli-Portici line, in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

The first railway line over Swiss territory was the Strasbourg–Basle line opened in 1844. Three years later, in 1847, the first fully Swiss railway line, the Spanisch Brötli Bahn, from Zürich to Baden was opened.

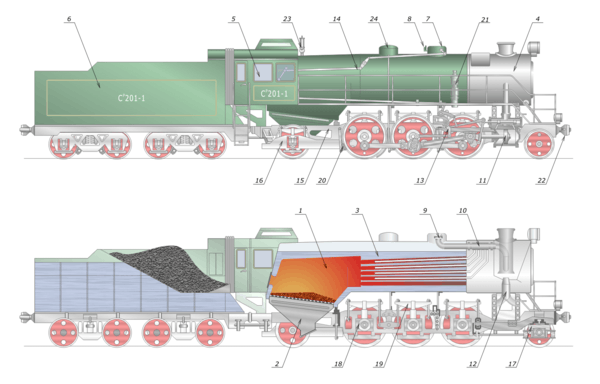

Basic form

- 01. Fire chamber

- 02. Ashpan

- 03. Water (inside the boiler)

- 04. Smoke box

- 05. Cab

- 06. Tender

- 07. Steam dome

- 08. Safety valve

- 09. Regulator valve

- 10. Super heater (in smoke box)

- 11. Piston

- 12. Blast pipe

- 13. Valve gear

- 14. Regulator rod

- 15. Drive frame

- 16. Rear Pony truck

- 17. Front Pony truck

- 18. Bearing and axle box

- 19. Leaf spring

- 20. Brake shoe

- 21. Air brake pump

- 22. (Front) Center coupler

- 23. Whistle

- 24. Sandbox

Boiler

The firebox fire-tube boiler has been the dominant source of power in the age of steam locomotion from the Rocket in 1829 to the Mallard in 1938. Although other types of boiler have been tried with steam locomotives, their use did not become widespread.

The steam locomotive, when fired up, typically employs a steel firebox fire-tube boiler that contains a heat source in the rear, which generates and maintains a head of steam within the pressurised partially water filled area in the front of the boiler.

The heat source, contained within the firebox, is the energy released by the combustion, typically of a solid or liquid fuel, creating a by-product of hot combustion gases. If wood, coal or coke is used as the combustion material it is introduced through a door, typically by a fireman, onto a set of grates where ashes fall away from the burning fuel. If oil is used as the fuel, a door allows adjusting of the air flow, maintenance and access for cleaning the oil jets.

The fire-tube boiler is characterised by internal tubes connected to the firebox that guide the smoke and hot combustion gases through the pressurised wet area of the boiler. These tubes greatly increase the contact area between the hot and the wet areas of the boiler, increasing the efficiency of the thermal conduction and thermal radiation processes of heat transfer between the two. The combustion gases emerge from the ends of the fire-tubes at the front of the boiler and are discharged via the smokebox to the chimney (stack or smokestack in the US). Surrounding the boiler are layers of insulation or lagging to minimize heat loss.

The amount of pressure in the boiler can be monitored by a gauge mounted in the cab and excessive steam pressure can be released manually by the driver or fireman. Alternatively, in conditions of high boiler pressure, a safety valve may be triggered to reduce pressure[17] and prevent the boiler bursting violently, which had previously resulted in injuries and fatalities to nearby individuals, as well as extensive damage to the locomotive and nearby structures.

At the front of the boiler is the smokebox, into which used exhaust steam is injected to increase the draught of smoke and combustion gases through the fire tubes in the boiler and out through the chimney. The search for thermal efficiency greater than that of the typical fire-tube boiler led such engineers as Nigel Gresley to consider innovations such as the water-tube boiler. Although he tested the concept on the LNER Class W1, the difficulties during development exceeded the will to solve the efficiency problem at the time.

The steam generated in the boiler not only propels the locomotive, but also energizes other devices such as whistles, brakes, pumps and passenger car heating systems. The constant demand for steam requires a continuous supply of water to the boiler, usually pumped in automatically. The source of this water is an unpressurised tank that is usually part of the locomotive's tender or is wrapped around the boiler in the case of a tank locomotive. Periodic stops are required to refill the water.

During operation, the boiler's water level is constantly monitored, normally via a transparent tube referred to as a sight glass, or with a gauge. Maintaining a proper water level is central to the efficient and safe operation of the boiler. If the water level is too high, steam production is decreased, efficiency is lost and in extreme cases, water will be carried out with the steam into the cylinders, possibly causing mechanical damage. More seriously, if the water level gets too low, the crown (top) and/or side sheets of the firebox may become exposed. Without sufficient water to absorb the heat of combustion, the firebox sheets may soften and melt, with the possible result of high-pressure steam being ejected with tremendous force through the firebox and into the locomotive's cab. The development of the fusible plug, a device to release pressure in conditions of excessively high temperature and low water levels was intended to protect against this occurrence.

Scale may build up in the boiler and prevent proper heat transfer, and corrosion will eventually degrade the boiler's materials to the point where it needs to be rebuilt or replaced. Start-up on a large engine may take hours of preliminary heating of the boiler water before sufficient steam is available.

Although the boiler is typically placed horizontally, for locomotives designed to work in locations with steep slopes it may be more appropriate to consider a vertical boiler or one mounted such that the boiler remains horizontal but the wheels are inclined to suit the slope of the rails.

Steam circuit

The steam generated in the boiler fills the space above the water in the partially filled boiler. Its maximum working pressure is limited by spring-loaded safety valves. It is then collected either in a perforated tube fitted above the water level or by a dome that often houses the regulator valve, or throttle, the purpose of which is to control the amount of steam leaving the boiler. The steam then either travels directly along and down a steam pipe to the engine unit or may first pass into the wet header of a superheater, the role of the latter being to improve thermal efficiency and eliminate water droplets suspended in the "saturated steam", the state in which it leaves the boiler. On leaving the superheater, the steam exits the dry header of the superheater and passes down a steam pipe, entering the steam chests adjacent to the cylinders of a reciprocating engine. Inside each steam chest is a sliding valve that distributes the steam via ports that connect the steam chest to the ends of the cylinder space. The role of the valves is twofold: admission of each fresh dose of steam, and exhaust of the used steam once it has done its work.

The cylinders are double-acting, with steam admitted to each side of the piston in turn. In a two-cylinder locomotive, one cylinder is located on each side of the vehicle. The cranks are set 90° out of phase. During a full rotation of the driving wheel, steam provides four power strokes; each cylinder receives two injections of steam per revolution. The first stroke is to the front of the piston and the second stroke to the rear of the piston; hence two working strokes. Consequently, two deliveries of steam onto each piston face in the two cylinders generates a full revolution of the driving wheel. Each piston is attached to the driving axle on each side by a connecting rod, and the driving wheels are connected together by coupling rods to transmit power from the main driver to the other wheels. Note that at the two "dead centres", when the connecting rod is on the same axis as the crankpin on the driving wheel, the connecting rod applies no torque to the wheel. Therefore, if both cranksets could be at "dead centre" at the same time, and the wheels should happen to stop in this position, the locomotive could not start moving. Therefore, the crankpins are attached to the wheels at a 90° angle to each other, so only one side can be at dead centre at a time.

Each piston transmits power directly through a connecting rod (Main rod in the US) and a crankpin (Wristpin in the US) on the driving wheel (Main driver in the US) or to a crank on a driving axle. The movement of the valves in the steam chest is controlled through a set of rods and linkages called the valve gear, actuated from the driving axle or from the crankpin; the valve gear includes devices that allow reversing the engine, adjusting valve travel and the timing of the admission and exhaust events. The cut-off point determines the moment when the valve blocks a steam port, "cutting off" admission steam and thus determining the proportion of the stroke during which steam is admitted into the cylinder; for example a 50% cut-off admits steam for half the stroke of the piston. The remainder of the stroke is driven by the expansive force of the steam. Careful use of cut-off provides economical use of steam and in turn reduces fuel and water consumption. The reversing lever (Johnson bar in the US), or screw-reverser (if so equipped), that controls the cut-off therefore performs a similar function to a gearshift in an automobile – maximum cut-off, providing maximum tractive effort at the expense of efficiency, is used to pull away from a standing start, whilst a cut-off as low as 10% is used when cruising, providing reduced tractive effort, and therefore lower fuel/water consumption.[18]

Exhaust steam is directed upwards out of the locomotive through the chimney, by way of a nozzle called a blastpipe, creating the familiar "chuffing" sound of the steam locomotive. The blastpipe is placed at a strategic point inside the smokebox that is at the same time traversed by the combustion gases drawn through the boiler and grate by the action of the steam blast. The combining of the two streams, steam and exhaust gases, is crucial to the efficiency of any steam locomotive, and the internal profiles of the chimney (or, strictly speaking, the ejector) require careful design and adjustment. This has been the object of intensive studies by a number of engineers (and often ignored by others, sometimes with catastrophic consequences). The fact that the draught depends on the exhaust pressure means that power delivery and power generation are automatically self-adjusting. Among other things, a balance has to be struck between obtaining sufficient draught for combustion whilst giving the exhaust gases and particles sufficient time to be consumed. In the past, a strong draught could lift the fire off the grate, or cause the ejection of unburnt particles of fuel, dirt and pollution for which steam locomotives had an unenviable reputation. Moreover, the pumping action of the exhaust has the counter-effect of exerting back pressure on the side of the piston receiving steam, thus slightly reducing cylinder power. Designing the exhaust ejector became a specific science, with engineers such as Chapelon, Giesl and Porta making large improvements in thermal efficiency and a significant reduction in maintenance time[19] and pollution.[20] A similar system was used by some early gasoline/kerosene tractor manufacturers (Advance-Rumely/Hart-Parr) – the exhaust gas volume was vented through a cooling tower, allowing the steam exhaust to draw more air past the radiator.

Running gear

Running gear includes the brake gear, wheel sets, axleboxes, springing and the motion that includes connecting rods and valve gear. The transmission of the power from the pistons to the rails and the behaviour of the locomotive as a vehicle, being able to negotiate curves, points and irregularities in the track, is of paramount importance. Because reciprocating power has to be directly applied to the rail from 0 rpm upwards, this creates the problem of adhesion of the driving wheels to the smooth rail surface. Adhesive weight is the portion of the locomotive's weight bearing on the driving wheels. This is made more effective if a pair of driving wheels is able to make the most of its axle load, i.e. its individual share of the adhesive weight. Locomotives with equalising beams connecting the ends of plate springs have often been deemed a complication, however locomotives fitted with the beams have usually been less prone to loss of traction due to wheel-slip.

Locomotives with total adhesion, where all of the wheels are coupled together, generally lack stability at speed. To counter this, locomotives often fit unpowered carrying wheels mounted on two-wheeled trucks or four-wheeled bogies centred by springs that help to guide the locomotive through curves. These usually take on weight – of the cylinders at the front or the firebox at the rear — when the width exceeds that of the mainframes. For multiple coupled-wheels on a rigid chassis, a variety of systems for controlled side-play exist.

Railroads generally preferred locomotives with fewer axles, to reduce maintenance costs. The number of axles required was dictated by the maximum axle loading of the railroad in question. A builder would typically add axles until the maximum weight on any one axle was acceptable to the railroad's maximum axle loading. A locomotive with a wheel arrangement of two lead axles, two drive axles, and one trailing axle was a high-speed machine. Two lead axles were necessary to have good tracking at high speeds. Two drive axles had a lower reciprocating mass than three, four, five or six coupled axles. They were thus able to turn at very high speeds due to the lower reciprocating mass. A trailing axle was able to support a huge firebox, hence most locomotives with the wheel arrangement of 4-4-2 (American Type Atlantic) were called free steamers and were able to maintain steam pressure regardless of throttle setting.

Chassis

The chassis, or locomotive frame, is the principal structure onto which the boiler is mounted and which incorporates the various elements of the running gear. The boiler is rigidly mounted on a "saddle" beneath the smokebox and in front of the boiler barrel, but the firebox at the rear is allowed to slide forward and backwards, to allow for expansion when hot.

European locomotives usually use "plate frames", where two vertical flat plates form the main chassis, with a variety of spacers and a buffer beam at each end to keep them apart. When inside cylinders are mounted between the frames, the plate frames are a single large casting that forms a major support. The axleboxes slide up and down to give some sprung suspension, against thickened webs attached to the frame, called "hornblocks".

American practice for many years was to use built-up bar frames, with the smokebox saddle/cylinder structure and drag beam integrated therein. In the 1920s, with the introduction of "superpower", the cast-steel locomotive bed became the norm, incorporating frames, spring hangers, motion brackets, smokebox saddle and cylinder blocks into a single complex, sturdy but heavy casting. André Chapelon developed a similar structure, welded instead of cast, causing a 30% saving in weight for the 2-10-4 locomotives, the construction of which was begun then abandoned in 1946.

Fuel and water

Generally, the largest locomotives are permanently coupled to a tender that carries the water and fuel. Often, locomotives working shorter distances do not have a tender and carry the fuel in a bunker, with the water carried in tanks placed next to the boiler either in two tanks alongside (side tank and pannier tank), one on top (saddle tank) or one underneath (well tank); these are called tank engines and usually have a 'T' suffix added to the Whyte notation, e.g. 0-6-0T.

The fuel used depended on what was economically available to the railway. In the UK and other parts of Europe, plentiful supplies of coal made this the obvious choice from the earliest days of the steam engine. Until 1870,[21] the majority of locomotives in the United States burned wood, but as the Eastern forests were cleared, coal gradually became more widely used. Thereafter, coal became and remained the dominant fuel worldwide until the end of general use of steam locomotives. Bagasse, a waste by-product of the refining process, was burned in sugar cane farming operations. In the US, the ready availability of oil made it a popular steam locomotive fuel after 1900 for the southwestern railroads, particularly the Southern Pacific. In the Australian state of Victoria after World War II, many steam locomotives were converted to heavy oil firing. German, Russian, Australian and British railways experimented with using coal dust to fire locomotives.

During World War II, a number of Swiss steam shunting locomotives were modified to use electrically heated boilers, consuming around 480 kW of power collected from an overhead line with a pantograph. These locomotives were significantly less efficient than electric ones; they were used because Switzerland had access to plentiful hydroelectricity, and suffered from a shortage of coal because of the war.[22]

A number of tourist lines and heritage locomotives in Switzerland, Argentina and Australia have used light diesel-type oil.[23]

Water was supplied at stopping places and locomotive depots from a dedicated water tower connected to water cranes or gantries. In the UK, the US and France, water troughs (track pans in the US) were provided on some main lines to allow locomotives to replenish their water supply without stopping, from rainwater or snowmelt that filled the trough due to inclement weather. This was achieved by using a deployable "water scoop" fitted under the tender or the rear water tank in the case of a large tank engine; the fireman remotely lowered the scoop into the trough, the speed of the engine forced the water up into the tank, and the scoop was raised again once it was full.

Water is an essential element in the operation of a steam locomotive. As Swengel argued:

It has the highest specific heat of any common substance; that is, more thermal energy is stored by heating water to a given temperature than would be stored by heating an equal mass of steel or copper to the same temperature. In addition, the property of vapourising (forming steam) stores additional energy without increasing the temperature... water is a very satisfactory medium for converting thermal energy of fuel into mechanical energy.[24]

Swengel went on to note that "at low temperature and relatively low boiler outputs", good water and regular boiler washout was an acceptable practice, even though such maintenance was high. As steam pressures increased, however, a problem of "foaming" or "priming" developed in the boiler, wherein dissolved solids in the water formed "tough-skinned bubbles" inside the boiler, which in turn were carried into the steam pipes and could blow off the cylinder heads. To overcome the problem, hot mineral-concentrated water was deliberately wasted (blown down) from the boiler periodically. Higher steam pressures required more blowing-down of water out of the boiler. Oxygen generated by boiling water attacks the boiler, and with increased steam pressure the rate of rust (iron oxide) generated inside the boiler increases. One way to help overcome the problem was water treatment. Swengel suggested that these problems contributed to the interest in electrification of railways.[24]

In the 1970s, L.D. Porta developed a sophisticated system of heavy-duty chemical water treatment (Porta Treatment) that not only keeps the inside of the boiler clean and prevents corrosion, but modifies the foam in such a way as to form a compact "blanket" on the water surface that filters the steam as it is produced, keeping it pure and preventing carry-over into the cylinders of water and suspended abrasive matter.[25][26]

Crew

A steam locomotive is normally controlled from the boiler's backhead, and the crew is usually protected from the elements by a cab. A crew of at least two people is normally required to operate a steam locomotive. One, the train driver, is responsible for controlling the locomotive's starting, stopping and speed, and the fireman is responsible for maintaining the fire, regulating steam pressure and monitoring boiler and tender water levels. Due to the historical loss of operational infrastructure and staffing, preserved steam locomotives operating on the mainline will often have a support crew travelling with the train.

Fittings and appliances

All locomotives are fitted with a variety of appliances. Some of these relate directly to the operation of the steam engine; while others are for signalling, train control or other purposes. In the United States, the Federal Railroad Administration mandated the use of certain appliances over the years in response to safety concerns. The most typical appliances are as follows:

Steam pumps and injectors

Water (feedwater) must be delivered to the boiler to replace that which is exhausted as steam after delivering a working stroke to the pistons. As the boiler is under pressure during operation, feedwater must be forced into the boiler at a pressure that is greater than the steam pressure, necessitating the use of some sort of pump. Early engines used pumps driven by the motion of the pistons (axle pumps), which were simple to operate and reliable, but only operated when the locomotive was moving, and could overload the valve gear and piston rods at high speeds. Steam injectors later replaced the pump, while some engines transitioned to turbopumps. Standard practice evolved to use two independent systems for feeding water to the boiler; either two steam injectors or, on more conservative designs, axle pumps when running at service speed and a steam injector for filling the boiler when stationary or at low speeds. By the 20th century virtually all new-built locomotives used only steam injectors – often one injector was supplied with "live" steam straight from the boiler itself and the other used exhaust steam from the locomotive's cylinders, which was more efficient (since it made use of otherwise wasted steam) but could only be used when the locomotive was in motion and the regulator was open.

Vertical glass tubes, known as water gauges or water glasses, show the level of water in the boiler and are carefully monitored at all times while the boiler is being fired. Before the 1870s it was more common to have a series of try-cocks fitted to the boiler within reach of the crew; each try cock (at least two and usually three were fitted) was mounted at a different level. By opening each try-cock and seeing if steam or water vented through it, the level of water in the boiler could be estimated with limited accuracy. As boiler pressures increased the use of try-cocks became increasingly dangerous and the valves were prone to blockage with scale or sediment, giving false readings. This led to their replacement with the sight glass. As with the injectors, two glasses with separate fittings were usually installed to provide independent readings.

Boiler lagging

Large amounts of heat are wasted if a boiler is not insulated. Early locomotives used shaped wooden battens fitted lengthways along the boiler barrel, and held in place by metal bands. Improved insulating methods included applying a thick paste containing a porous mineral such as kieselgur, or attaching shaped blocks of insulating compound such as magnesia blocks.[27] In the latter days of steam, "mattresses" of stitched asbestos cloth stuffed with asbestos fibre were fixed to the boiler, on separators so as not quite to touch the boiler. However, asbestos is currently banned in most countries for health reasons. The most common modern day material is glass wool, or wrappings of aluminium foil.

The lagging is protected by a close-fitted sheet-metal casing[28] known as boiler clothing or cleading.

Effective lagging is particularly important for fireless locomotives; however in recent times under the influence of L.D. Porta, "exaggerated" insulation has been practised for all types of locomotive on all surfaces liable to dissipate heat, such as cylinder ends and facings between the cylinders and the mainframes. This considerably reduces engine warmup time with marked increase in overall efficiency.

Safety valves

Early locomotives were fitted with a valve controlled by a weight suspended from the end of a lever, with the steam outlet being stopped by a cone-shaped valve. As there was nothing to prevent the weighted lever from bouncing when the locomotive ran over irregularities in the track, thus wasting steam, the weight was later replaced by a more stable spring-loaded column, often supplied by Salter, a well-known spring scale manufacturer. The danger of these devices was that the driving crew could be tempted to add weight to the arm to increase pressure. Most early boilers were fitted with a tamper-proof "lockup" direct-loaded ball valve protected by a cowl. In the late 1850s, John Ramsbottom introduced a safety valve that became popular in Britain during the latter part of the 19th century. Not only was this valve tamper-proof, but tampering by the driver could only have the effect of easing pressure. George Richardson's safety valve was an American invention introduced in 1875,[29] and was designed to release the steam only at the moment when the pressure attained the maximum permitted. This type of valve is in almost universal use at present. Britain's Great Western Railway was a notable exception to this rule, retaining the direct-loaded type until the end of its separate existence, because it was considered that such a valve lost less pressure between opening and closing.

Pressure gauge

The earliest locomotives did not show the pressure of steam in the boiler, but it was possible to estimate this by the position of the safety valve arm which often extended onto the firebox back plate; gradations marked on the spring column gave a rough indication of the actual pressure. The promoters of the Rainhill trials urged that each contender have a proper mechanism for reading the boiler pressure, and Stephenson devised a nine-foot vertical tube of mercury with a sight-glass at the top, mounted alongside the chimney, for his Rocket. The Bourdon tube gauge, in which the pressure straightens an oval-section coiled tube of brass or bronze connected to a pointer, was introduced in 1849 and quickly gained acceptance, and is still used today.[30] Some locomotives have an additional pressure gauge in the steam chest. This helps the driver avoid wheel-slip at startup, by warning if the regulator opening is too great.

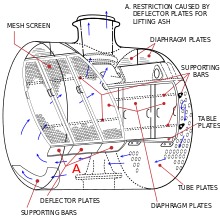

Spark arrestors and smokeboxes

- Spark arrestor and self-cleaning smokebox

Wood-burners emit large quantities of flying sparks which necessitate an efficient spark-arresting device generally housed in the smokestack. Many different types were fitted,[31] the most common early type being the Bonnet stack that incorporated a cone-shaped deflector placed before the mouth of the chimney pipe, and a wire screen covering the wide stack exit. A more-efficient design was the Radley and Hunter centrifugal stack patented in 1850 (commonly known as the diamond stack), incorporating baffles so oriented as to induce a swirl effect in the chamber that encouraged the embers to burn out and fall to the bottom as ash. In the self-cleaning smokebox the opposite effect was achieved: by allowing the flue gasses to strike a series of deflector plates, angled in such a way that the blast was not impaired, the larger particles were broken into small pieces that would be ejected with the blast, rather than settle in the bottom of the smokebox to be removed by hand at the end of the run. As with the arrestor, a screen was incorporated to retain any large embers.[32]

Locomotives of the British Railways standard classes fitted with self-cleaning smokeboxes were identified by a small cast oval plate marked "S.C.", fitted at the bottom of the smokebox door. These engines required different disposal procedures and the plate highlighted this need to depot staff.

Stokers

A factor that limits locomotive performance is the rate at which fuel is fed into the fire. In the early 20th century some locomotives became so large that the fireman could not shovel coal fast enough.[28] In the United States, various steam-powered mechanical stokers became standard equipment and were adopted and used elsewhere including Australia and South Africa.

Feedwater heating

Introducing cold water into a boiler reduces power, and from the 1920s a variety of heaters were incorporated. The most common type for locomotives was the exhaust steam feedwater heater that piped some of the exhaust through small tanks mounted on top of the boiler or smokebox or into the tender tank; the warm water then had to be delivered to the boiler by a small auxiliary steam pump. The rare economiser type differed in that it extracted residual heat from the exhaust gases. An example of this is the pre-heater drum(s) found on the Franco-Crosti boiler.

The use of live steam and exhaust steam injectors also assists in the pre-heating of boiler feedwater to a small degree, though there is no efficiency advantage to live steam injectors. Such pre-heating also reduces the thermal shock that a boiler might experience when cold water is introduced directly. This is further helped by the top feed, where water is introduced to the highest part of the boiler and made to trickle over a series of trays. G.J. Churchward fitted this arrangement to the high end of his domeless coned boilers. Other British lines such as the LBSCR fitted some locomotives with the top feed inside a separate dome forward of the main one.

Condensers and water re-supply

Steam locomotives consume vast quantities of water because they operate on an open cycle, expelling their steam immediately after a single use rather than recycling it in a closed loop as stationary and marine steam engines do. Water was a constant logistical problem, and condensing engines were devised for use in desert areas. These engines had huge radiators in their tenders and instead of exhausting steam out of the funnel it was captured, passed back to the tender and condensed. The cylinder lubricating oil was removed from the exhausted steam to avoid a phenomenon known as priming, a condition caused by foaming in the boiler which would allow water to be carried into the cylinders causing damage because of its incompressibility. The most notable engines employing condensers (Class 25, the "puffers which never puff"[33]) worked across the Karoo desert of South Africa from the 1950s until the 1980s.

Some British and American locomotives were equipped with scoops which collected water from "water troughs" (track pans in the US) while in motion, thus avoiding stops for water. In the US, small communities often did not have refilling facilities. During the early days of railroading, the crew simply stopped next to a stream and filled the tender using leather buckets. This was known as "jerking water" and led to the term "jerkwater towns" (meaning a small town, a term which today is considered derisive).[34] In Australia and South Africa, locomotives in drier regions operated with large oversized tenders and some even had an additional water wagon, sometimes called a "canteen" or in Australia (particularly in New South Wales) a "water gin".

Steam locomotives working on underground railways (such as London's Metropolitan Railway) were fitted with condensing apparatus to prevent steam from escaping into the railway tunnels. These were still being used between King's Cross and Moorgate into the early 1960s.

Braking

Locomotives have their own braking system, independent from the rest of the train. Locomotive brakes employ large shoes which press against the driving wheel treads. With the advent of air brakes, a separate system also allowed the driver to control the brakes on all cars. These systems require steam-powered compressors, which are mounted on the side of the boiler or on the smokebox front. Almost all of these compressors were of the Westinghouse single-stage or cross-compound variety. Such systems operated in the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

An alternative to the air brake is the vacuum brake, in which a steam-operated ejector is mounted on the engine instead of the air pump, to create a vacuum and release the brakes. A secondary ejector or crosshead vacuum pump is used to maintain the vacuum in the system against the small leaks in the pipe connections between carriages and wagons. Vacuum systems existed on British, Indian, West Australian and South African railway networks.

Steam locomotives are nearly always fitted with sandboxes from which sand can be delivered to the rails to improve traction and braking in wet or icy weather. On American locomotives the sandboxes, or sand domes, are usually mounted on top of the boiler. In Britain, the limited loading gauge precludes this, so the sandboxes are mounted just above, or just below, the running plate.

Lubrication

The pistons and valves on the earliest locomotives were lubricated by the enginemen dropping a lump of tallow down the blast pipe.[35]

As speeds and distances increased, mechanisms were developed that injected thick mineral oil into the steam supply. The first, a displacement lubricator, mounted in the cab, uses a controlled stream of steam condensing into a sealed container of oil. Water from the condensed steam displaces the oil into pipes. The apparatus is usually fitted with sight-glasses to confirm the rate of supply. A later method uses a mechanical pump worked from one of the crossheads. In both cases, the supply of oil is proportional to the speed of the locomotive.

Lubricating the frame components (axle bearings, horn blocks and bogie pivots) depends on capillary action: trimmings of worsted yarn are trailed from oil reservoirs into pipes leading to the respective component.[36] The rate of oil supplied is controlled by the size of the bundle of yarn and not the speed of the locomotive, so it is necessary to remove the trimmings (which are mounted on wire) when stationary. However, at regular stops (such as a terminating station platform), oil finding its way onto the track can still be a problem.

Crank pin and crosshead bearings carry small cup-shaped reservoirs for oil. These have feed pipes to the bearing surface that start above the normal fill level, or are kept closed by a loose-fitting pin, so that only when the locomotive is in motion does oil enter. In United Kingdom practice the cups are closed with simple corks, but these have a piece of porous cane pushed through them to admit air. It is customary for a small capsule of pungent oil (aniseed or garlic) to be incorporated in the bearing metal to warn if the lubrication fails and excess heating or wear occurs.[37]

Blower

When the locomotive is running under power, a draught on the fire is created by the exhaust steam directed up the chimney by the blastpipe. Without draught, the fire will quickly die down and steam pressure will fall. When the locomotive is stopped, or coasting with the regulator closed, there is no exhaust steam to create a draught, so the draught is maintained by means of a blower. This is a ring placed either around the base of the chimney, or around the blast pipe orifice, containing several small steam nozzles directed up the chimney. These nozzles are fed with steam directly from the boiler, controlled by the blower valve. When the regulator is open, the blower valve is closed; when the driver intends to close the regulator, he will first open the blower valve. It is important that the blower be opened before the regulator is closed, since without draught on the fire, there may be backdraught – where atmospheric air blows down the chimney, causing the flow of hot gases through the boiler tubes to be reversed, with the fire itself being blown through the firehole onto the footplate, with serious consequences for the crew. The risk of backdraught is higher when the locomotive enters a tunnel because of the pressure shock. The blower is also used to create draught when steam is being raised at the start of the locomotive's duty, at any time when the driver needs to increase the draught on the fire, and to clear smoke from the driver's line of vision.[38]

Blowbacks were fairly common. In a 1955 report on an accident near Dunstable, the Inspector wrote, "In 1953 twenty-three cases, which were not caused by an engine defect, were reported and they resulted in 26 enginemen receiving injuries. In 1954 the number of occurrences and of injuries were the same and there was also one fatal casualty."[39] They remain a problem, as evidenced by the 2012 incident with BR standard class 7 70013 Oliver Cromwell.

Buffers

In British and European (except former Soviet Union countries) practice, locomotives usually have buffers at each end to absorb compressive loads ("buffets"[40]). The tensional load of drawing the train (draft force) is carried by the coupling system. Together these control slack between the locomotive and train, absorb minor impacts and provide a bearing point for pushing movements.

In Canadian and American practice all of the forces between the locomotive and cars are handled through the coupler – particularly the Janney coupler, long standard on American railroad rolling stock – and its associated draft gear, which allows some limited slack movement. Small dimples called "poling pockets" at the front and rear corners of the locomotive allowed cars to be pushed onto an adjacent track using a pole braced between the locomotive and the cars.[41] In Britain and Europe, North American style "buckeye" and other couplers that handle forces between items of rolling stock have become increasingly popular.

Pilots

A pilot was usually fixed to the front end of locomotives, although in European and a few other railway systems including New South Wales, they were considered unnecessary. Plough-shaped, sometimes called "cow catchers", they were quite large and were designed to remove obstacles from the track such as cattle, bison, other animals or tree limbs. Though unable to "catch" stray cattle, these distinctive items remained on locomotives until the end of steam. Switching engines usually replaced the pilot with small steps, known as footboards. Many systems used the pilot and other design features to produce a distinctive appearance.

Headlights

When night operations began, railway companies in some countries equipped their locomotives with lights to allow the driver to see what lay ahead of the train, or to enable others to see the locomotive. Headlights were originally oil or acetylene lamps, but when electric arc lamps became available in the late 1880s, they quickly replaced the older types.

Britain did not adopt bright headlights as they would affect night vision and so could mask the low-intensity oil lamps used in the semaphore signals and at each end of trains, increasing the danger of missing signals, especially on busy tracks. Locomotive stopping distances were also normally much greater than the range of headlights, and the railways were well-signalled and fully fenced to prevent livestock and people from straying onto them, largely negating the need for bright lamps. Thus low-intensity oil lamps continued to be used, positioned on the front of locomotives to indicate the class of each train. Four "lamp irons" (brackets on which to place the lamps) were provided: one below the chimney and three evenly spaced across the top of the buffer beam. The exception to this was the Southern Railway and its constituents, who added an extra lamp iron each side of the smokebox, and the arrangement of lamps (or in daylight, white circular plates) told railway staff the origin and destination of the train. On all vehicles, equivalent lamp irons were also provided on the rear of the locomotive or tender for when the locomotive was running tender- or bunker-first.

In some countries, heritage steam operation continues on the national network. Some railway authorities have mandated powerful headlights on at all times, including during daylight. This was to further inform the public or track workers of any active trains.

Bells and whistles

Locomotives used bells and steam whistles from earliest days of steam locomotion. In the United States, India and Canada, bells warned of a train in motion. In Britain, where all lines are by law fenced throughout,[42] bells were only a requirement on railways running on a road (i.e. not fenced off), for example a tramway along the side of the road or in a dockyard. Consequently, only a minority of locomotives in the UK carried bells. Whistles are used to signal personnel and give warnings. Depending on the terrain the locomotive was being used in, the whistle could be designed for long-distance warning of impending arrival, or for more localised use.

Early bells and whistles were sounded through pull-string cords and levers. Automatic bell ringers came into widespread use in the US after 1910.[43]

Automatic control

From the early 20th century operating companies in such countries as Germany and Britain began to fit locomotives with in-cab signalling (AWS), which automatically applied the brakes when a signal was passed at "caution". In Britain, these became mandatory in 1956. In the United States, the Pennsylvania Railroad also fitted their locomotives with such devices.

Booster engines

In the United States and Australia, the trailing truck was often equipped with an auxiliary steam engine which provided extra power for starting. This booster engine was set to cut-out automatically at a certain speed. On the narrow-gauged New Zealand railway system, six Kb 4-8-4 locomotives were fitted with boosters, the only 3-foot-6-inch-gauge (1,070 mm) engines in the world to have such equipment.

Variations

Numerous variations on the basic locomotive occurred as railways attempted to improve efficiency and performance.

Cylinders

Early steam locomotives had two cylinders, one either side, and this practice persisted as the simplest arrangement. The cylinders could be mounted between the main frames (known as "inside" cylinders), or mounted outside the frames and driving wheels ("outside" cylinders). Inside cylinders are driven by cranks built into the driving axle; outside cylinders are driven by cranks on extensions to the driving axles.

Later designs employed three or four cylinders, mounted both inside and outside the frames, for a more even power cycle and greater power output.[44] This was at the expense of more complicated valve gear and increased maintenance requirements. In some cases the third cylinder was added inside simply to allow for smaller diameter outside cylinders, and hence reduce the width of the locomotive for use on lines with a restricted loading gauge, for example the SR K1 and U1 classes.

Most British express-passenger locomotives built between 1930 and 1950 were 4-6-0 or 4-6-2 types with three or four cylinders (e.g. GWR 6000 Class, LMS Coronation Class, SR Merchant Navy Class, LNER Gresley Class A3). From 1951, all but one of the 999 new British Rail standard class steam locomotives across all types used 2-cylinder configurations for easier maintenance.

Valve gear

Early locomotives used a simple valve gear that gave full power in either forward or reverse.[30] Soon the Stephenson valve gear allowed the driver to control cut-off; this was largely superseded by Walschaerts valve gear and similar patterns. Early locomotive designs using slide valves and outside admission were relatively easy to construct, but inefficient and prone to wear.[30] Eventually, slide valves were superseded by inside admission piston valves, though there were attempts to apply poppet valves (commonly used in stationary engines) in the 20th century. Stephenson valve gear was generally placed within the frame and was difficult to access for maintenance; later patterns applied outside the frame were more readily visible and maintained.

Compounding

Compound locomotives were used from 1876, expanding the steam twice or more through separate cylinders – reducing thermal losses caused by cylinder cooling. Compound locomotives were especially useful in trains where long periods of continuous efforts were needed. Compounding contributed to the dramatic increase in power achieved by André Chapelon's rebuilds from 1929. A common application was in articulated locomotives, the most common being that designed by Anatole Mallet, in which the high-pressure stage was attached directly to the boiler frame; in front of this was pivoted a low-pressure engine on its own frame, which takes the exhaust from the rear engine.[45]

Articulated locomotives

More-powerful locomotives tend to be longer, but long rigid-framed designs are impractical for the tight curves frequently found on narrow-gauge railways. Various designs for articulated locomotives were developed to overcome this problem. The Mallet and the Garratt were the two most popular, both using a single boiler and two engines (sets of cylinders and driving wheels). The Garratt has two power bogies, whereas the Mallet has one. There were also a few examples of triplex locomotives that had a third engine under the tender. Both the front and tender engines were low-pressure compounded, though they could be operated simple (high-pressure) for starting off. Other less common variations included the Fairlie locomotive, which had two boilers back-to-back on a common frame, with two separate power bogies.

Duplex types

Duplex locomotives, containing two engines in one rigid frame, were also tried, but were not notably successful. For example, the 4-4-4-4 Pennsylvania Railroad's T1 class, designed for very fast running, suffered recurring and ultimately unfixable slippage problems throughout their careers.[46]

Geared locomotives

For locomotives where a high starting torque and low speed were required, the conventional direct drive approach was inadequate. "Geared" steam locomotives, such as the Shay, the Climax and the Heisler, were developed to meet this need on industrial, logging, mine and quarry railways. The common feature of these three types was the provision of reduction gearing and a drive shaft between the crankshaft and the driving axles. This arrangement allowed the engine to run at a much higher speed than the driving wheels compared to the conventional design, where the ratio is 1:1.

Cab forward

In the United States on the Southern Pacific Railroad, a series of cab forward locomotives were produced with the cab and the firebox at the front of the locomotive and the tender behind the smokebox, so that the engine appeared to run backwards. This was only possible by using oil-firing. Southern Pacific selected this design to provide air free of smoke for the engine driver to breathe as the locomotive passed through mountain tunnels and snow sheds. Another variation was the Camelback locomotive, with the cab situated halfway along the boiler. In England, Oliver Bulleid developed the SR Leader class locomotive during the nationalisation process in the late 1940s. The locomotive was heavily tested but several design faults (such as coal firing and sleeve valves) meant that this locomotive and the other part-built locomotives were scrapped. The cab-forward design was taken by Bulleid to Ireland, where he moved after nationalisation, where he developed the "turfburner". This locomotive was more successful, but was scrapped due to the dieselisation of the Irish railways.

The only preserved cab forward locomotive is Southern Pacific 4294 in Sacramento, California.

In France, the three Heilmann locomotives were built with a cab forward design.

Steam turbines

Steam turbines were created as an attempt to improve the operation and efficiency of steam locomotives. Experiments with steam turbines using direct-drive and electrical transmissions in various countries proved mostly unsuccessful.[28] The London, Midland and Scottish Railway built the Turbomotive, a largely successful attempt to prove the efficiency of steam turbines.[28] Had it not been for the outbreak of World War II, more may have been built. The Turbomotive ran from 1935 to 1949, when it was rebuilt into a conventional locomotive because many parts required replacement, an uneconomical proposition for a "one-off" locomotive. In the United States, Union Pacific, Chesapeake and Ohio and Norfolk & Western (N&W) railways all built turbine-electric locomotives. The Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) also built turbine locomotives, but with a direct-drive gearbox. However, all designs failed due to dust, vibration, design flaws or inefficiency at lower speeds. The final one remaining in service was the N&W's, retired in January 1958. The only truly successful design was the TGOJ MT3, used for hauling iron ore from Grängesberg in Sweden to the ports of Oxelösund. Despite functioning correctly, only three were built. Two of them are preserved in working order in museums in Sweden.

Hybrid power

Mixed power locomotives, utilising both steam and diesel propulsion, have been produced in Russia, Britain and Italy.

Under unusual conditions (lack of coal, abundant hydroelectricity) some locomotives in Switzerland were modified to use electricity to heat the boiler, making them electric-steam locomotives.[47]

Fireless locomotive

In a fireless locomotive the boiler is replaced by a steam accumulator, which is charged with steam (actually water at a temperature well above boiling point, 212 °F/100 °C) from a stationary boiler. Fireless locomotives were used where there was a high fire risk (e.g. in oil refineries), where cleanliness was important (e.g. in food factories) or where steam is readily available (e.g. in paper mills and power stations where steam is either a by-product or is cheaply available). The water vessel ("boiler") is heavily insulated the same as with a fired locomotive. Until all the water has boiled away, the steam pressure does not drop except as the temperature drops. Another class of fireless locomotive is a compressed-air locomotive.

Steam-electric locomotive

A steam-electric locomotive is similar in concept to a diesel-electric locomotive, except that a steam engine instead of a diesel engine is used to drive a generator. Three such locomotives were built by the French engineer Jean Jacques Heilmann in the 1890s.

Manufacture

Most manufactured classes

.jpg)

The most-manufactured single class of steam locomotive in the world is the 0-10-0 Russian locomotive class E steam locomotive with around 11,000 produced both in Russia and other countries such as Czechoslovakia, Germany, Sweden, Hungary and Poland. The Russian locomotive class O numbered 9,129 locomotives, built between 1890 and 1928. Around 7,000 units were produced of the German DRB Class 52 2-10-0 Kriegslok. The British GWR 5700 class numbered about 863 units. The DX class of the London and North Western Railway numbered 943 units, including 86 engines built for the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway.[48]

United Kingdom

Before the 1923 Grouping Act, production in the UK was mixed. The larger railway companies built locomotives in their own workshops, with the smaller ones and industrial concerns ordering them from outside builders. A large market for outside builders existed due to the home-build policy exercised by the main railway companies. An example of a pre-grouping works was the one at Melton Constable, which maintained and built some of the locomotives for the Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway. Other works included one at Boston (an early GNR building) and Horwich works.

Between 1923 and 1947, the "Big Four" railway companies (the Great Western Railway, the London, Midland and Scottish Railway, the London and North Eastern Railway and the Southern Railway) all built most of their own locomotives, only buying locomotives from outside builders when their own works were fully occupied (or as a result of government-mandated standardisation during wartime).[49]

From 1948, British Railways allowed the former "Big Four" companies (now designated as "Regions") to continue to produce their own designs, but also created a range of standard locomotives which supposedly combined the best features from each region. Although a policy of "dieselisation" was adopted in 1955, BR continued to build new steam locomotives until 1960, with the final engine being named Evening Star.

Some independent manufacturers produced steam locomotives for a few more years, with the last British-built industrial steam locomotive being constructed by Hunslet in 1971. Since then, a few specialised manufacturers have continued to produce small locomotives for narrow gauge and miniature railways, but as the prime market for these is the tourist and heritage railway sector, the demand for such locomotives is limited. In November 2008, a new build main line steam locomotive, 60163 Tornado, was tested on UK mainlines for eventual charter and tour use.

Sweden

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, most Swedish steam locomotives were manufactured in Britain. Later, however, most steam locomotives were built by local factories including NOHAB in Trollhättan and ASJ in Falun. One of the most successful types was the class "B" (4-6-0), inspired by the Prussian class P8. Many of the Swedish steam locomotives were preserved during the Cold War in case of war. During the 1990s, these steam locomotives were sold to non-profit associations or abroad, which is why the Swedish class B, class S (2-6-4) and class E2 (2-8-0) locomotives can now be seen in Britain, the Netherlands, Germany and Canada.

United States

Railroad locomotive engines in the United States have nearly always been built in and for United States railroads with very few imports, except in the earliest days of steam engines. This is due to the basic differences of markets in the United States which initially had many small markets located large distances apart, in contrast to Europe's higher density of markets. Locomotives that were cheap and rugged and could go large distances over cheaply built and maintained tracks were required. Once the manufacture of engines was established on a wide scale there was very little advantage to buying an engine from overseas that would have to be customised to fit the local requirements and track conditions. Improvements in engine design of both European and US origin were incorporated by manufacturers when they could be justified in a generally very conservative and slow-changing market. With the notable exception of the USRA standard locomotives built during World War I, in the United States, steam locomotive manufacture was always semi-customised. Railroads ordered locomotives tailored to their specific requirements, though some basic design features were always present. Railroads developed some specific characteristics; for example, the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Great Northern Railway had a preference for the Belpaire firebox.[50] In the United States, large-scale manufacturers constructed locomotives for nearly all rail companies, although nearly all major railroads had shops capable of heavy repairs and some railroads (for example, the Norfolk and Western Railway and the Pennsylvania Railroad, which had two erecting shops) constructed locomotives entirely in their own shops. Companies manufacturing locomotives in the US included Baldwin Locomotive Works, American Locomotive Company (Alco), and Lima Locomotive Works. Altogether, between 1830 and 1950, over 160,000 steam locomotives were built in the United States.[51]

Steam locomotives required regular and, compared to a diesel-electric engine, frequent service and overhaul (often at government-regulated intervals in Europe and the US). Alterations and upgrades regularly occurred during overhauls. New appliances were added, unsatisfactory features removed, cylinders improved or replaced. Almost any part of the locomotive, including boilers, was replaced or upgraded. When service or upgrades got too expensive the locomotive was traded off or retired. On the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad two 2-10-2 locomotives were dismantled; the boilers were placed onto two new Class T 4-8-2 locomotives and the residual wheel machinery made into a pair of Class U 0-10-0 switchers with new boilers. Union Pacific's fleet of 3-cylinder 4-10-2 engines were converted into two-cylinder engines in 1942, because of high maintenance problems.

Australia

In Sydney, Clyde Engineering and the workshops in Eveleigh both built steam locomotives for the New South Wales Government Railways. These include the C38 class 4-6-2; the first five were built at Clyde with streamlining, the other 25 locomotives were built at Eveleigh (13) and Cardiff Workshops (12) near Newcastle. In Queensland, steam locomotives were locally constructed by Walkers. Similarly the South Australian state government railways also manufactured steam locomotives locally at Islington Railway Workshops in Adelaide. Victorian Railways constructed most of their locomotives at their Newport Workshops and in Bendigo, while in the early days locomotives were built at the Phoenix Foundry in Ballarat. Locomotives constructed at the Newport shops ranged from the nA class 2-6-2T built for the narrow gauge, up to the H class 4-8-4 – the largest conventional locomotive ever to operate in Australia, weighing 260 tons. However, the title of largest locomotive ever used in Australia goes to the 263-ton NSWGR AD60 class 4-8-4+4-8-4 Garratt,[52] built by Beyer-Peacock in the United Kingdom. Most steam locomotives used in Western Australia were built in the United Kingdom, though some examples were designed and built locally at the Western Australian Government Railways' Midland Railway Workshops. The 10 WAGR S class locomotives (introduced in 1943) were the only class of steam locomotive to be wholly conceived, designed and built in Western Australia,[53] while the Midland workshops notably participated in the Australia-wide construction program of Australian Standard Garratts – these wartime locomotives were built at Midland in Western Australia, Clyde Engineering in New South Wales, Newport in Victoria and Islington in South Australia and saw varying degrees of service in all Australian states.[53]

Categorisation

Steam locomotives are categorised by their wheel arrangement. The two dominant systems for this are the Whyte notation and UIC classification.

The Whyte notation, used in most English-speaking and Commonwealth countries, represents each set of wheels with a number. These numbers typically represented the number of un-powered leading wheels, followed by the number of driving wheels (sometimes in several groups), followed by the number of un-powered trailing wheels. For example, a yard engine with only 4 drive wheels would be categorised as a "0-4-0" wheel arrangement. A locomotive with a 4-wheel leading truck, followed by 6 drive wheels, and a 2-wheel trailing truck, would be classed as a "4-6-2". Different arrangements were given names which usually reflect the first usage of the arrangement; for instance the "Santa Fe" type (2-10-2) is so called because the first examples were built for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. These names were informally given and varied according to region and even politics.

The UIC classification is used mostly in European countries apart from the United Kingdom. It designates consecutive pairs of wheels (informally "axles") with a number for non-driving wheels and a capital letter for driving wheels (A=1, B=2, etc.) So a Whyte 4-6-2 designation would be an equivalent to a 2-C-1 UIC designation.

On many railroads, locomotives were organised into classes. These broadly represented locomotives which could be substituted for each other in service, but most commonly a class represented a single design. As a rule classes were assigned some sort of code, generally based on the wheel arrangement. Classes also commonly acquired nicknames, such as "Pugs", representing notable (and sometimes uncomplimentary) features of the locomotives.[54][55]

Performance

Measurement

In the steam locomotive era, two measures of locomotive performance were generally applied. At first, locomotives were rated by tractive effort, defined as the average force developed during one revolution of the driving wheels at the rail head.[24] This can be roughly calculated by multiplying the total piston area by 85% of the boiler pressure (a rule of thumb reflecting the slightly lower pressure in the steam chest above the cylinder), and dividing by the ratio of the driver diameter over the piston stroke. However, the precise formula is:

- .

where d is the bore of the cylinder (diameter) in inches, s is the cylinder stroke, in inches, P is boiler pressure in pounds per square inch, D is the diameter of the driving wheel in inches, and c is a factor that depends on the effective cut-off.[56] In the US, c is usually set at 0.85, but lower on engines that have maximum cutoff limited to 50–75%.

The tractive effort is only the "average" force, as not all effort is constant during the one revolution of the drivers. At some points of the cycle only one piston is exerting turning moment and at other points both pistons are working. Not all boilers deliver full power at starting, and the tractive effort also decreases as the rotating speed increases.[24]

Tractive effort is a measure of the heaviest load a locomotive can start or haul at very low speed over the ruling grade in a given territory.[24] However, as the pressure grew to run faster goods and heavier passenger trains, tractive effort was seen to be an inadequate measure of performance because it did not take into account speed. Therefore, in the 20th century, locomotives began to be rated by power output. A variety of calculations and formulas were applied, but in general railways used dynamometer cars to measure tractive force at speed in actual road testing.

British railway companies have been reluctant to disclose figures for drawbar horsepower and have usually relied on continuous tractive effort instead.

Relation to wheel arrangement

Whyte classification is indirectly connected to locomotive performance. Given adequate proportions of the rest of the locomotive, power output is determined by the size of the fire, and for a bituminous coal-fuelled locomotive, this is determined by the grate area. Modern non-compound locomotives are typically able to produce about 40 drawbar horsepower per square foot of grate. Tractive force, as noted earlier, is largely determined by the boiler pressure, the cylinder proportions and the size of the driving wheels. However, it is also limited by the weight on the driving wheels (termed "adhesive weight"), which needs to be at least four times the tractive effort.[28]

The weight of the locomotive is roughly proportional to the power output; the number of axles required is determined by this weight divided by the axleload limit for the trackage where the locomotive is to be used. The number of driving wheels is derived from the adhesive weight in the same manner, leaving the remaining axles to be accounted for by the leading and trailing bogies.[28] Passenger locomotives conventionally had two-axle leading bogies for better guidance at speed; on the other hand, the vast increase in the size of the grate and firebox in the 20th century meant that a trailing bogie was called upon to provide support. In Europe, some use was made of several variants of the Bissel bogie in which the swivelling movement of a single axle truck controls the lateral displacement of the front driving axle (and in one case the second axle too). This was mostly applied to 8-coupled express and mixed traffic locomotives, and considerably improved their ability to negotiate curves whilst restricting overall locomotive wheelbase and maximising adhesion weight.

As a rule, "shunting engines" (US: switching engines) omitted leading and trailing bogies, both to maximise tractive effort available and to reduce wheelbase. Speed was unimportant; making the smallest engine (and therefore smallest fuel consumption) for the tractive effort was paramount. Driving wheels were small and usually supported the firebox as well as the main section of the boiler. Banking engines (US: helper engines) tended to follow the principles of shunting engines, except that the wheelbase limitation did not apply, so banking engines tended to have more driving wheels. In the US, this process eventually resulted in the Mallet type engine with its many driven wheels, and these tended to acquire leading and then trailing bogies as guidance of the engine became more of an issue.

As locomotive types began to diverge in the late 19th century, freight engine designs at first emphasised tractive effort, whereas those for passenger engines emphasised speed. Over time, freight locomotive size increased, and the overall number of axles increased accordingly; the leading bogie was usually a single axle, but a trailing truck was added to larger locomotives to support a larger firebox that could no longer fit between or above the driving wheels. Passenger locomotives had leading bogies with two axles, fewer driving axles, and very large driving wheels in order to limit the speed at which the reciprocating parts had to move.

In the 1920s, the focus in the United States turned to horsepower, epitomised by the "super power" concept promoted by the Lima Locomotive Works, although tractive effort was still the prime consideration after World War I to the end of steam. Goods trains were designed to run faster, while passenger locomotives needed to pull heavier loads at speed. This was achieved by increasing the size of grate and firebox without changes to the rest of the locomotive, requiring the addition of a second axle to the trailing truck. Freight 2-8-2s became 2-8-4s while 2-10-2s became 2-10-4s. Similarly, passenger 4-6-2s became 4-6-4s. In the United States this led to a convergence on the dual-purpose 4-8-4 and the 4-6-6-4 articulated configuration, which was used for both freight and passenger service.[57] Mallet locomotives went through a similar transformation, evolving from bank engines into huge mainline locomotives with much larger fireboxes; their driving wheels were also increased in size in order to allow faster running.

The end of steam in general use

Steam railroading is a pain in the butt.— George Thagard, owner of the Sandstone Crag Loop Line, 2006[58]

The introduction of electric locomotives around the turn of the 20th century and later diesel-electric locomotives spelled the beginning of a decline in the use of steam locomotives, although it was some time before they were phased out of general use.[59] As diesel power (especially with electric transmission) became more reliable in the 1930s, it gained a foothold in North America.[60] The full transition away from steam power in North America took place during the 1950s. In continental Europe, large-scale electrification had replaced steam power by the 1970s. Steam was a familiar technology, adapted well to local facilities, and also consumed a wide variety of fuels; this led to its continued use in many countries until the end of the 20th century.

Steam engines have considerably less thermal efficiency than modern diesels, requiring constant maintenance and labour to keep them operational.[61] Water is required at many points throughout a rail network, making it a major problem in desert areas, as are found in some regions of the United States, Australia and South Africa. In places where water is available, it may be hard, which can cause "scale" to form, composed mainly of calcium carbonate, magnesium hydroxide and calcium sulfate. Calcium and magnesium carbonates tend to be deposited as off-white solids on the inside the surfaces of pipes and heat exchangers. This precipitation is principally caused by thermal decomposition of bicarbonate ions but also happens in cases where the carbonate ion is at saturation concentration.[62] The resulting build-up of scale restricts the flow of water in pipes. In boilers, the deposits impair the flow of heat into the water, reducing the heating efficiency and allowing the metal boiler components to overheat.

The reciprocating mechanism on the driving wheels of a two-cylinder single expansion steam locomotive tended to pound the rails (see hammer blow), thus requiring more maintenance. Raising steam from coal took a matter of hours, and created serious pollution problems. Coal-burning locomotives required fire cleaning and ash removal between turns of duty.[63] Diesel or electric locomotives, by comparison, drew benefit from new custom-built servicing facilities. The smoke from steam locomotives was also deemed objectionable; the first electric and diesel locomotives were developed in response to smoke abatement requirements,[64] although this did not take into account the high level of less-visible pollution in diesel exhaust smoke, especially when idling. In some countries, however, power for electric locomotives is derived from steam generated in power stations, which are often run by coal.

United States decline

Diesel locomotives began to appear in mainline service in the United States in the mid-1930s.[65] The diesel engines reduced maintenance costs dramatically, while increasing locomotive availability. On the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad the new units delivered over 350,000 miles (560,000 km) a year, compared with about 120,000–150,000 miles (190,000–240,000 km) for a mainline steam locomotive.[28] World War II delayed dieselisation in the US. In 1949 the Gulf, Mobile and Ohio Railroad became the first large mainline railroad to convert completely to diesel locomotives, and Life Magazine ran an article on 5 December 1949 titled "The GM&O puts all its steam engines to torch, becomes first major US railroad to dieselize 100%".[66] The last steam locomotive manufactured for general service was a Norfolk and Western 0-8-0, built in its Roanoke shops in December, 1953.[67] 1960 is normally considered the final year of regular Class 1 main line standard gauge steam operation in the United States, with operations on the Grand Trunk Western, Illinois Central, Norfolk and Western and Duluth Missabe and Iron Range Railroads,[68] as well as Canadian Pacific operations in Maine.[69]