Standing wave

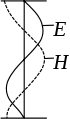

In physics, a standing wave – also known as a stationary wave – is a wave in a medium in which each point on the axis of the wave has an associated constant amplitude. The locations at which the amplitude is minimum are called nodes, and the locations where the amplitude is maximum are called antinodes.

Standing waves were first noticed by Michael Faraday in 1831. Faraday observed standing waves on the surface of a liquid in a vibrating container.[1][2] Franz Melde coined the term "standing wave" (German: stehende Welle or Stehwelle) around 1860 and demonstrated the phenomenon in his classic experiment with vibrating strings.[3][4][5][6]

This phenomenon can occur because the medium is moving in the opposite direction to the wave, or it can arise in a stationary medium as a result of interference between two waves traveling in opposite directions. The most common cause of standing waves is the phenomenon of resonance, in which standing waves occur inside a resonator due to interference between waves reflected back and forth at the resonator's resonant frequency.

For waves of equal amplitude traveling in opposing directions, there is on average no net propagation of energy.

Moving medium

As an example of the first type, under certain meteorological conditions standing waves form in the atmosphere in the lee of mountain ranges. Such waves are often exploited by glider pilots.

Standing waves and hydraulic jumps also form on fast flowing river rapids and tidal currents such as the Saltstraumen maelstrom. Many standing river waves are popular river surfing breaks.

Opposing waves

|

|

|

|

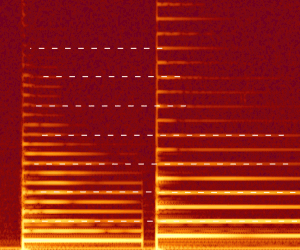

As an example of the second type, a standing wave in a transmission line is a wave in which the distribution of current, voltage, or field strength is formed by the superposition of two waves of the same frequency propagating in opposite directions. The effect is a series of nodes (zero displacement) and anti-nodes (maximum displacement) at fixed points along the transmission line. Such a standing wave may be formed when a wave is transmitted into one end of a transmission line and is reflected from the other end by an impedance mismatch, i.e., discontinuity, such as an open circuit or a short.[7] The failure of the line to transfer power at the standing wave frequency will usually result in attenuation distortion.

In practice, losses in the transmission line and other components mean that a perfect reflection and a pure standing wave are never achieved. The result is a partial standing wave, which is a superposition of a standing wave and a traveling wave. The degree to which the wave resembles either a pure standing wave or a pure traveling wave is measured by the standing wave ratio (SWR).[8]

Another example is standing waves in the open ocean formed by waves with the same wave period moving in opposite directions. These may form near storm centres, or from reflection of a swell at the shore, and are the source of microbaroms and microseisms.

Mathematical description

In one dimension, two waves with the same frequency, wavelength and amplitude traveling in opposite directions will interfere and produce a standing wave or stationary wave. For example: a wave traveling to the right along a taut string held stationary at its right end will reflect back in the other direction along the string, and the two waves will superpose to produce a standing wave. The reflected wave has to have the same amplitude and frequency as the incoming wave. The phenomenon can be demonstrated mathematically by deriving the equation for the sum of two oppositely moving waves:

A harmonic wave traveling to the right along the x-axis is described by the equation

An identical harmonic wave traveling to the left is described by the equation

where:

- is the amplitude of the wave,

- (called the angular frequency and measured in radians per second) is 2π times the frequency (in hertz)

- is the wavelength of the wave (in metres)

- and are variables for longitudinal position and time, respectively.

So the equation of the resultant wave y will be the sum of y1 and y2:

Using the trigonometric sum-to-product identity to simplify:

This describes a wave that oscillates in time, but has a spatial dependence that is stationary; at any point x the amplitude of the oscillations is constant with value . At locations which are even multiples of a quarter wavelength

called the nodes, the amplitude is always zero, whereas at locations which are odd multiples of a quarter wavelength

called the anti-nodes, the amplitude is maximum, with a value of twice the amplitude of the original waves. The distance between two consecutive nodes or anti-nodes is λ/2.

Standing waves can also occur in two- or three-dimensional resonators. With standing waves on two-dimensional membranes such as drumheads, illustrated in the animations above, the nodes become nodal lines, lines on the surface at which there is no movement, that separate regions vibrating with opposite phase. These nodal line patterns are called Chladni figures. In three-dimensional resonators, such as musical instrument sound boxes and microwave cavity resonators, there are nodal surfaces.

Examples

One easy example to understand standing waves is two people shaking either end of a jump rope. If they shake in sync the rope can form a regular pattern of waves oscillating up and down, with stationary points along the rope where the rope is almost still (nodes) and points where the arc of the rope is maximum (antinodes)

Sound waves

Standing waves are also observed in physical media such as strings and columns of air. Any waves traveling along the medium will reflect back when they reach the end. This effect is most noticeable in musical instruments where, at various multiples of a vibrating string or air column's natural frequency, a standing wave is created, allowing harmonics to be identified. Nodes occur at fixed ends and anti-nodes at open ends. If fixed at only one end, only odd-numbered harmonics are available. At the open end of a pipe the anti-node will not be exactly at the end as it is altered by its contact with the air and so end correction is used to place it exactly. The density of a string will affect the frequency at which harmonics will be produced; the greater the density the lower the frequency needs to be to produce a standing wave of the same harmonic.

Visible light

Standing waves are also observed in optical media such as optical wave guides, optical cavities, etc. Lasers use optical cavities in the form of a pair of facing mirrors. The gain medium in the cavity (such as a crystal) emits light coherently, exciting standing waves of light in the cavity. The wavelength of light is very short (in the range of nanometers, 10−9 m) so the standing waves are microscopic in size. One use for standing light waves is to measure small distances, using optical flats.

X-rays

Interference between X-ray beams can form an X-ray standing wave (XSW) field.[11] Because of the short wavelength of X-rays (less than 1 nanometer), this phenomenon can be exploited for measuring atomic-scale events at material surfaces. The XSW is generated in the region where an X-ray beam interferes with a diffracted beam from a nearly perfect single crystal surface or a reflection from an X-ray mirror. By tuning the crystal geometry or X-ray wavelength, the XSW can be translated in space, causing a shift in the X-ray fluorescence or photoelectron yield from the atoms near the surface. This shift can be analyzed to pinpoint the location of a particular atomic species relative to the underlying crystal structure or mirror surface. The XSW method has been used to clarify the atomic-scale details of dopants in semiconductors,[12] atomic and molecular adsorption on surfaces,[13] and chemical transformations involved in catalysis.[14]

Mechanical waves

Standing waves can be mechanically induced into a solid medium using resonance. One easy to understand example is two people shaking either end of a jump rope. If they shake in sync, the rope will form a regular pattern with nodes and antinodes and appear to be stationary, hence the name standing wave. Similarly a cantilever beam can have a standing wave imposed on it by applying a base excitation. In this case the free end moves the greatest distance laterally compared to any location along the beam. Such a device can be used as a sensor to track changes in frequency or phase of the resonance of the fiber. One application is as a measurement device for dimensional metrology.[15][16]

Seismic waves

Standing surface waves on the Earth are observed as free oscillations of the Earth.

Faraday waves

The Faraday wave is a non-linear standing wave at the air-liquid interface induced by hydrodynamic instability. It can be used as a liquid-based template to assemble microscale materials.[17]

See also

- Amphidromic point, Clapotis, Longitudinal mode, Modelocking, Metachronal rhythm. Resonant room modes, Seiche, Trumpet, Voltage standing wave ratio, Wave, Kundt's tube

References and notes

- ↑ Alwyn Scott (ed), Encyclopedia of Nonlinear Science, p. 683, Routledge, 2006 ISBN 1135455589.

- ↑ Theodore Y. Wu, "Stability of nonlinear waves resonantly sustained", Nonlinear Instability of Nonparallel Flows: IUTAM Symposium Potsdam, New York, p. 368, Springer, 2012 ISBN 3642850847.

- ↑ Melde, Franz. Ueber einige krumme Flächen, welche von Ebenen, parallel einer bestimmten Ebene, durchschnitten, als Durchschnittsfigur einen Kegelschnitt liefern: Inaugural-Dissertation... Koch, 1859.

- ↑ Melde, Franz. "Ueber die Erregung stehender Wellen eines fadenförmigen Körpers." Annalen der Physik 185, no. 2 (1860): 193-215.

- ↑ Melde, Franz. Die Lehre von den Schwingungscurven...: mit einem Atlas von 11 Tafeln in Steindruck. JA Barth, 1864.

- ↑ Melde, Franz. "Akustische Experimentaluntersuchungen." Annalen der Physik 257, no. 3 (1884): 452-470.

- ↑

This article incorporates public domain material from the General Services Administration document "Federal Standard 1037C".

This article incorporates public domain material from the General Services Administration document "Federal Standard 1037C". - ↑ Blackstock, David T. (2000), Fundamentals of Physical Acoustics, Wiley–IEEE, ISBN 0-471-31979-1, 568 pages. See page 141.

- ↑ A Wave Dynamical Interpretation of Saturn's Polar Region, M. Allison, D. A. Godfrey, R. F. Beebe, Science vol. 247, pg. 1061 (1990)

- ↑ A laboratory model of Saturn’s North Polar Hexagon, A. C. Barbosa Aguiar, P. L. Read, R. D. Wordsworth, T. Salter, Y. H. Yamazaki, Icarus, vol. 206 (2009)

- ↑ B.W. Batterman; H. Cole (1964), Dynamical Diffraction of X Rays by Perfect Crystals, Rev. Mod. Phys., 36 681

- ↑ B.W. Batterman, Detection of Foreign Atom Sites by Their X-Ray Fluorescence Scattering, Phys. Rev. Lett., 22 703

- ↑ J.A. Golovchenko; J.R. Patel; D.R. Kaplan; P.L. Cowan; M.J. Bedzyk (1982), Solution to the Surface Registration Problem Using X-Ray Standing Waves, Phys. Rev. Lett., 49 560

- ↑ Z. Feng; C.-Y. Kim; J.W. Elam; Q. Ma; Z. Zhang; M.J. Bedzyk (2009), Direct Atomic-Scale Observation of Redox-Induced Cation Dynamics in an Oxide-Supported Monolayer Catalyst: WOx/α-Fe2O3(0001), J. Am. Chem. Soc., 131 18200-18201

- ↑ M.B. Bauza; R.J Hocken; S.T Smith; S.C Woody (2005), The development of a virtual probe tip with application to high aspect ratio microscale features, Rev. Sci Instrum, 76 (9) 095112 .

- ↑ http://www.insitutec.com

- ↑ P. Chen, Z. Luo, S. Guven, S. Tasoglu, A. Weng, A. V. Ganesan, U. Demirci, Advanced Materials 2014, 10.1002/adma.201402079. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/adma.201402079/abstract

External links

- Simulation of standing waves in a room using WebGL

- Java applet of standing waves on a vibrating string

- Java applet of transverse standing wave

- Java applet showing the production of standing wave on a string by adjusting frequency

- Simulation of standing wave diagrams including the reflection coefficient, input impedance, SWR, etc.