Glucose

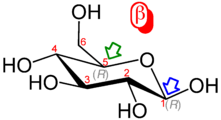

α-D-glucopyranose (chair form). | |

Haworth projection of α-D-glucopyranose | |

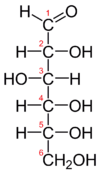

Fischer projection of D-glucose | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈɡluːkoʊz/, /ˈɡluːkoʊs/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name

D-Glucose | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(2R,3S,4R,5R)-2,3,4,5,6-Pentahydroxyhexanal | |

| Other names

Blood sugar Dextrose Corn sugar D-Glucose Grape sugar | |

| Identifiers | |

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|

| 3DMet | B04623 |

| Abbreviations | Glc |

| 1281604 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| EC Number | 200-075-1 |

| 83256 | |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Glucose |

| PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number | LZ6600000 |

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C6H12O6 | |

| Molar mass | 180.16 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | White powder |

| Density | 1.54 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | α-D-glucose: 146 °C (295 °F; 419 K) β-D-glucose: 150°C (302°F; 423 K) |

| 909 g/1 L (25 °C (77 °F)) | |

| -101.5·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| 8.6827 | |

| Thermochemistry | |

| 218.6 J K−1 mol−1[1] | |

| Std molar entropy (S |

209.2 J K−1 mol−1[1] |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH |

−1271 kJ/mol [2] |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH |

−2805 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| B05CX01 (WHO) V04CA02 (WHO), V06DC01 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | ICSC 08655 |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula C6H12O6. Glucose circulates in the blood of animals as blood sugar. It is made during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, using energy from sunlight. It is the most important source of energy for cellular respiration. Glucose is stored as a polymer, in plants as starch and in animals as glycogen.

With 6 carbon atoms, it is classed as a hexose, a subcategory of the monosaccharides. D-Glucose is one of the 16 aldohexose stereoisomers. The D-isomer, D-glucose, also known as dextrose, occurs widely in nature, but the L-isomer, L-glucose, does not. Glucose can be obtained by hydrolysis of carbohydrates such as milk sugar, cane sugar, maltose, cellulose, glycogen, etc. It is commonly commercially manufactured from cornstarch by hydrolysis via pressurized steaming at controlled pH in a jet followed by further enzymatic depolymerization.[3]

In 1747, Andreas Marggraf was the first to isolate glucose.[4] Glucose is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[5] The name glucose derives through the French from the Greek γλυκός, which means "sweet," in reference to must, the sweet, first press of grapes in the making of wine.[6][7] The suffix "-ose" is a chemical classifier, denoting a carbohydrate.

Function in biology

Glucose is the most widely used aldohexose in living organisms. One possible explanation for this is that glucose has a lower tendency than other aldohexoses to react nonspecifically with the amine groups of proteins.[8] This reaction – glycation – impairs or destroys the function of many proteins.[8] Glucose's low rate of glycation can be attributed to it having a more stable cyclic form compared to other aldohexoses, which means it spends less time than they do in its reactive open-chain form.[8] The reason for glucose having the most stable cyclic form of all the aldohexoses is that its hydroxy groups (with the exception of the hydroxy group on the anomeric carbon of D-glucose) are in the equatorial position. Many of the long-term complications of diabetes (e.g., blindness, renal failure, and peripheral neuropathy) are probably due to the glycation of proteins or lipids.[9] In contrast, enzyme-regulated addition of sugars to protein is called glycosylation and is essential for the function of many proteins.[10]

Energy source

Glucose is a ubiquitous fuel in biology. It is used as an energy source in most organisms, from bacteria to humans, through either aerobic respiration, anaerobic respiration, or fermentation. Glucose is the human body's key source of energy, through aerobic respiration, providing about 3.75 kilocalories (16 kilojoules) of food energy per gram.[11] Breakdown of carbohydrates (e.g. starch) yields mono- and disaccharides, most of which is glucose. Through glycolysis and later in the reactions of the citric acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation, glucose is oxidized to eventually form CO2 and water, yielding energy mostly in the form of ATP. The insulin reaction, and other mechanisms, regulate the concentration of glucose in the blood.

Glucose supplies almost all the energy for the brain,[12] so its availability influences psychological processes. When glucose is low, psychological processes requiring mental effort (e.g., self-control, effortful decision-making) are impaired.[13][14][15][16]

As a result of its importance in human health, glucose is an analyte in common medical blood tests.[17] Eating or fasting prior to taking a blood sample has an effect on analyses for glucose in the blood; a high fasting glucose blood sugar level may be a sign of prediabetes or diabetes mellitus.

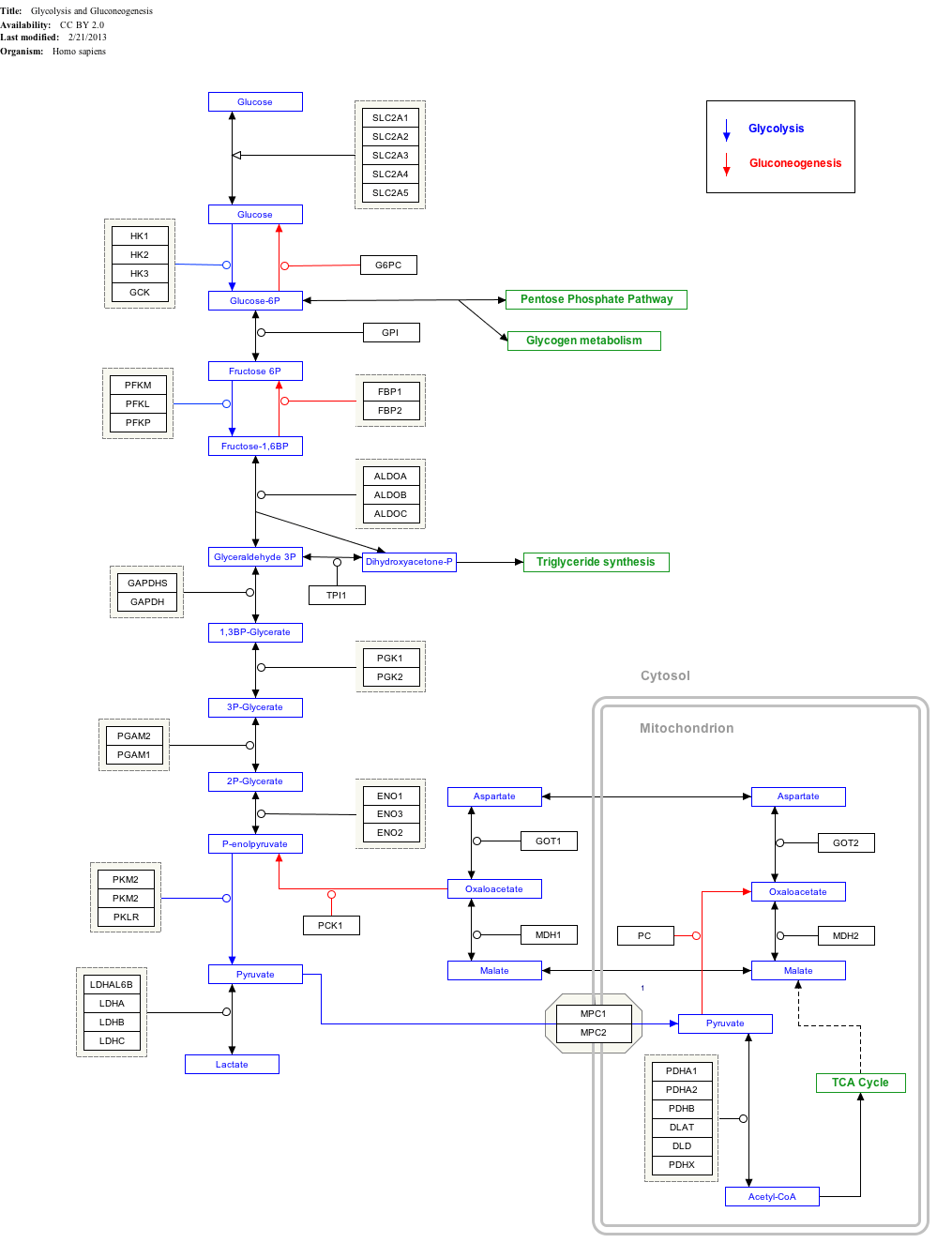

Glycolysis

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Compound C00031 at KEGG Pathway Database. Enzyme 2.7.1.1 at KEGG Pathway Database. Compound C00668 at KEGG Pathway Database. Reaction R01786 at KEGG Pathway Database. | ||||||||||||||||||||

Glucose-containing compounds and isomeric forms are digested and taken up by the body in the intestines, including starch, glycogen, disaccharides and monosaccharides.

Glucose is stored in mainly the liver and muscles as glycogen.

It is distributed and used in tissues as free glucose.

Use of glucose as an energy source in cells is by either aerobic respiration, anaerobic respiration, or fermentation. All of these processes follow from an earlier metabolic pathway known as glycolysis. The first step of glycolysis is the phosphorylation of glucose by a hexokinase to form glucose 6-phosphate. The main reason for the immediate phosphorylation of glucose is to prevent its diffusion out of the cell as the charged phosphate group prevents glucose 6-phosphate from easily crossing the cell membrane.[18] Furthermore, addition of the high-energy phosphate group activates glucose for subsequent breakdown in later steps of glycolysis. At physiological conditions, this initial reaction is irreversible.

In anaerobic respiration, one glucose molecule produces a net gain of two ATP molecules (four ATP molecules are produced during glycolysis through substrate-level phosphorylation, but two are required by enzymes used during the process).[19] In aerobic respiration, a molecule of glucose is much more profitable in that a maximum net production of 30 or 32 ATP molecules (depending on the organism) through oxidative phosphorylation is generated.[20]

Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles. [§ 1]

|{{{bSize}}}px|alt=Glycolysis and Gluconeogenesis edit]]

Glycolysis and Gluconeogenesis edit

- ↑ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "GlycolysisGluconeogenesis_WP534".

Precursors

Organisms use glucose as a precursor for the synthesis of several important substances. Starch, cellulose, and glycogen ("animal starch") are common glucose polymers (polysaccharides). Some of these polymers (starch or glycogen) serve as energy stores, while others (cellulose and chitin, which is made from a derivative of glucose) have structural roles. Oligosaccharides of glucose combined with other sugars serve as important energy stores. These include lactose, the predominant sugar in milk, which is a glucose-galactose disaccharide, and sucrose, another disaccharide which is composed of glucose and fructose. Glucose is also added onto certain proteins and lipids in a process called glycosylation. This is often critical for their functioning. The enzymes that join glucose to other molecules usually use phosphorylated glucose to power the formation of the new bond by coupling it with the breaking of the glucose-phosphate bond.

Other than its direct use as a monomer, glucose can be broken down to synthesize a wide variety of other biomolecules. This is important, as glucose serves both as a primary store of energy and as a source of organic carbon. Glucose can be broken down and converted into lipids. It is also a precursor for the synthesis of other important molecules such as vitamin C (ascorbic acid).

Medical uses

Glucose in diabetes

Diabetes is a metabolic disorder where the body is unable to regulate levels of glucose in the blood either because of a lack of insulin in the body or the failure, by cells in the body, to respond properly to insulin. Both of these situations can be caused by persistently high elevations of blood glucose levels, through pancreatic burnout and insulin resistance. The pancreas is the organ responsible for the secretion of insulin. Insulin is a hormone that regulates glucose levels, allowing the body's cells to absorb and use glucose. Without it, glucose cannot enter the cell and therefore cannot be used as fuel for the body's functions.[21] If the pancreas is exposed to persistently high elevations of blood glucose levels, the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas could be damaged, causing a lack of insulin in the body. Insulin resistance occurs when the pancreas tries to produce more and more insulin in response to persistently elevated blood glucose levels. Eventually, the rest of the body becomes resistant to the insulin that the pancreas is producing, thereby requiring more insulin to achieve the same blood glucose-lowering effect, and forcing the pancreas to produce even more insulin to compete with the resistance. This negative spiral contributes to pancreatic burnout, and the disease progression of diabetes.

To monitor the body's response to blood glucose-lowering therapy, glucose levels can be measured. Blood glucose monitoring can be performed by multiple methods, such as the fasting glucose test which measures the level of glucose in the blood after 8 hours of fasting. Another test is the 2-hour glucose tolerance test (GTT) – for this test, the person has a fasting glucose test done, then drinks a 75-gram glucose drink and is retested. This test measures the ability of the person's body to process glucose. Over time the blood glucose levels should decrease as insulin allows it to be taken up by cells and exit the blood stream.

Hypoglycemia management

Individuals with diabetes or other conditions where hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) may occur often carry small amounts of sugar in various forms. One sugar commonly used is glucose, often in the form of glucose tablets (glucose pressed into a tablet shape sometimes with one or more other ingredients as a binder), hard candy, or sugar packet.

Structure and nomenclature

Glucose is a monosaccharide with formula C6H12O6 or H-(C=O)-(CHOH)5-H, whose five hydroxyl (OH) groups are arranged in a specific way along its six-carbon back.

Open-chain form

In its fleeting open-chain form, the glucose molecule has an open (as opposed to cyclic) and unbranched backbone of six carbon atoms, C-1 through C-6; where C-1 is part of an aldehyde group H(C=O)-, and each of the other five carbons bears one hydroxyl group -OH. The remaining bonds of the backbone carbons are satisfied by hydrogen atoms -H. Therefore, glucose is both a hexose and an aldose, or an aldohexose. The aldehyde group makes glucose a reducing sugar giving a positive reaction with the Fehling test.

Each of the four carbons C-2 through C-5 is a stereocenter, meaning that its four bonds connect to four different substituents. (Carbon C-2, for example, connects to -(C=O)H, -OH, -H, and -(CHOH)4H.) In D-glucose, these four parts must be in a specific three-dimensional arrangement. Namely, when the molecule is drawn in the Fischer projection, the hydroxyls on C-2, C-4, and C-5 must be on the right side, while that on C-3 must be on the left side.

The positions of those four hydroxyls are exactly reversed in the Fischer diagram of L-glucose. D- and L-glucose are two of the 16 possible aldohexoses; the other 14 are allose, altrose, mannose, gulose, idose, galactose, and talose, each with two enantiomers, "D-" and "L-".

The aldehyde form of glucose

The aldehyde form of glucose

It is important to note that the linear form of glucose makes up less than 3% of the glucose molecules in a water solution. The rest is one of two cyclic forms of glucose that are formed when the hydroxyl group on carbon 5 (C5) bonds to the aldehyde carbon 1 (C1).

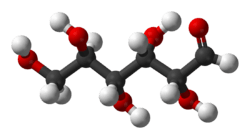

Cyclic forms

.

From left to right: Haworth projections and ball-and-stick structures of the α- and β- anomers of D-glucopyranose (top row) and D-glucofuranose (bottom row)

In solutions, the open-chain form of glucose (either "D-" or "L-") exists in equilibrium with several cyclic isomers, each containing a ring of carbons closed by one oxygen atom. In aqueous solution however, more than 99% of glucose molecules, at any given time, exist as pyranose forms. The open-chain form is limited to about 0.25% and furanose forms exists in negligible amounts. The terms "glucose" and "D-glucose" are generally used for these cyclic forms as well. The ring arises from the open-chain form by an intramolecular nucleophilic addition reaction between the aldehyde group (at C-1) and either the C-4 or C-5 hydroxyl group, forming a hemiacetal linkage, -C(OH)H-O-.

The reaction between C-1 and C-5 yields a six-membered heterocyclic system called a pyranose, which is a monosaccharide sugar (hence "–ose") containing a derivatised pyran skeleton. The (much rarer) reaction between C-1 and C-4 yields a five-membered furanose ring, named after the cyclic ether furan. In either case, each carbon in the ring has one hydrogen and one hydroxyl attached, except for the last carbon (C-4 or C-5) where the hydroxyl is replaced by the remainder of the open molecule (which is -(C(CH2OH)HOH)-H or -(CHOH)-H, respectively).

The ring-closing reaction makes carbon C-1 chiral, too, since its four bonds lead to -H, to -OH, to carbon C-2, and to the ring oxygen. These four parts of the molecule may be arranged around C-1 (the anomeric carbon) in two distinct ways, designated by the prefixes "α-" and "β-". When a glucopyranose molecule is drawn in the Haworth projection, the designation "α-" means that the hydroxyl group attached to C-1 and the -CH2OH group at C-5 lies on opposite sides of the ring's plane (a trans arrangement), while "β-" means that they are on the same side of the plane (a cis arrangement). Therefore, the open-chain isomer D-glucose gives rise to four distinct cyclic isomers: α-D-glucopyranose, β-D-glucopyranose, α-D-glucofuranose, and β-D-glucofuranose. These five structures exist in equilibrium and interconvert, and the interconversion is much more rapid with acid catalysis.

The other open-chain isomer L-glucose similarly gives rise to four distinct cyclic forms of L-glucose, each the mirror image of the corresponding D-glucose.

The rings are not planar, but are twisted in three dimensions. The glucopyranose ring (α or β) can assume several non-planar shapes, analogous to the "chair" and "boat" conformations of cyclohexane. Similarly, the glucofuranose ring may assume several shapes, analogous to the "envelope" conformations of cyclopentane.

In the solid state, only the glucopyranose forms are observed, forming colorless crystalline solids that are highly soluble in water and acetic acid but poorly soluble in methanol and ethanol. They melt at 146 °C (295 °F) (α) and 150 °C (302 °F) (β), and decompose at higher temperatures into carbon and water.

Rotational isomers

Each glucose isomer is subject to rotational isomerism. Within the cyclic form of glucose, rotation may occur around the O6-C6-C5-O5 torsion angle, termed the ω-angle, to form three staggered rotamer conformations called gauche-gauche (gg), gauche-trans (gt) and trans-gauche (tg).[22] There is a tendency for the ω-angle to adopt a gauche conformation, a tendency that is attributed to the gauche effect.

Physical properties

Solutions

All forms of glucose are colorless and easily soluble in water, acetic acid, and several other solvents. They are only sparingly soluble in methanol and ethanol.

The open-chain form is thermodynamically unstable, and it spontaneously isomerizes to the cyclic forms. (Although the ring closure reaction could in theory create four- or three-atom rings, these would be highly strained, and are not observed in practice.) In solutions at room temperature, the four cyclic isomers interconvert over a time scale of hours, in a process called mutarotation.[23] Starting from any proportions, the mixture converges to a stable ratio of α:β 36:64. The ratio would be α:β 11:89 if it were not for the influence of the anomeric effect.[24] Mutarotation is considerably slower at temperatures close to 0 °C (32 °F).

Mutarotation consists of a temporary reversal of the ring-forming reaction, resulting in the open-chain form, followed by a reforming of the ring. The ring closure step may use a different -OH group than the one recreated by the opening step (thus switching between pyranose and furanose forms), or the new hemiacetal group created on C-1 may have the same or opposite handedness as the original one (thus switching between the α and β forms). Thus, though the open-chain form is barely detectable in solution, it is an essential component of the equilibrium.

Solid state

Depending on conditions, three major solid forms of glucose can be crystallised from water solutions: α-glucopyranose, β-glucopyranose, and β-glucopyranose hydrate.[25]

Optical activity

Whether in water or in the solid form, D- (+) glucose is dextrorotatory, meaning it will rotate the direction of polarized light clockwise. The effect is due to the chirality of the molecules, and indeed the mirror-image isomer, L- (-)glucose, is levorotatory (rotates polarized light counterclockwise) by the same amount. The strength of the effect is different for each of the five tautomers.

Note that the D- prefix does not refer directly to the optical properties of the compound. It indicates that the C-5 chiral center has the same handedness as that of D-glyceraldehyde (which was so labeled because it is dextrorotatory). The fact that D-glucose is dextrorotatory is a combined effect of its four chiral centers, not just of C-5; and indeed some of the other D-aldohexoses are levorotatory.

Production

| Metabolism of common monosaccharides and some biochemical reactions of glucose |

|---|

|

Biosynthesis

In plants and some prokaryotes, glucose is a product of photosynthesis. In plants, and in animals and fungi, glucose also is produced by the breakdown of polymeric forms of glucose—glycogen (animals, fungi) or starch (plants); the cleavage of glycogen is termed glycogenolysis, of starch, starch degradation.[26] In animals, glucose is synthesized in the liver and kidneys from non-carbohydrate intermediates, such as pyruvate, lactate and glycerol, in the process of gluconeogenesis. In some deep-sea bacteria, glucose is produced by chemosynthesis.

Commercial

Glucose is produced commercially via the enzymatic hydrolysis of starch. Many crops can be used as the source of starch. Maize, rice, wheat, cassava, corn husk and sago are all used in various parts of the world. In the United States, corn starch (from maize) is used almost exclusively. Most commercial glucose occurs as a component of invert sugar, a roughly 1:1 mixture of glucose and fructose. In principle, cellulose could be hydrolysed to glucose, but this process is not yet commercially practical.[25] Glucose syrup, also known as corn syrup, is essentially a purified aqueous solution of saccharides obtained from edible starch that has a dextrose equivalency (DE) of 20 or more. Dried corn syrup is glucose syrup with the water removed. Glucose has a DE of 100; dried maltodextrin has a DE of less than 20. Corn syrup itself has a DE between 20 and 95.[27]

Sources and absorption

Most dietary carbohydrates contain glucose, either as their only building block (as in the polysaccharides starch and glycogen), or together with another monosaccharide (as in the hetero-polysaccharides sucrose and lactose).[28]

In the lumen of the duodenum and small intestine, the glucose oligo- and polysaccharides are broken down to monosaccharides by the pancreatic and intestinal glycosidases. Other polysaccharides cannot be processed by the human intestine and require assistance by intestinal flora if they are to be broken down; the most notable exceptions are sucrose (fructose-glucose) and lactose (galactose-glucose). Glucose is then transported across the apical membrane of the enterocytes by SLC5A1 (SGLT1), and later across their basal membrane by SLC2A2 (GLUT2).[29]

Some glucose is converted to lactic acid by astrocytes, which is then utilized as an energy source by brain cells; some glucose is used by intestinal cells and red blood cells, while the rest reaches the liver, adipose tissue and muscle cells, where it is absorbed and stored as glycogen (under the influence of insulin). Liver cell glycogen can be converted to glucose and returned to the blood when insulin is low or absent; muscle cell glycogen is not returned to the blood because of a lack of enzymes. In fat cells, glucose is used to power reactions that synthesize some fat types and have other purposes. Glycogen is the body's "glucose energy storage" mechanism, because it is much more "space efficient" and less reactive than glucose itself.

History

Glucose was first isolated from raisins in 1747 by the German chemist Andreas Marggraf.[4][30] Because glucose is a basic necessity of many organisms, a correct understanding of its chemical makeup and structure contributed greatly to a general advancement in organic chemistry. This understanding occurred largely as a result of the investigations of Emil Fischer, a German chemist who received the 1902 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his findings.[31] The synthesis of glucose established the structure of organic material and consequently formed the first definitive validation of Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff's theories of chemical kinetics and the arrangements of chemical bonds in carbon-bearing molecules.[32] Between 1891 and 1894, Fischer established the stereochemical configuration of all the known sugars and correctly predicted the possible isomers, applying van 't Hoff's theory of asymmetrical carbon atoms.

Research

Glucose physical and chemical properties have been used to build a computational model of protein-glucose binding-sites.[33]

See also

- 2,5-Dimethylfuran, a potential glucose-based biofuel

- Caramelization

- Fludeoxyglucose (18F)

- Glucan

- Glucose transporter (GLUT)

References

- 1 2 Boerio-Goates, Juliana (1991), "Heat-capacity measurements and thermodynamic functions of crystalline α-D-glucose at temperatures from 10K to 340K", J. Chem. Thermodynam., 23 (5): 403–9, doi:10.1016/S0021-9614(05)80128-4

- ↑ Ponomarev, V. V.; Migarskaya, L. B. (1960), "Heats of combustion of some amino-acids", Russ. J. Phys. Chem. (Engl. Transl.), 34: 1182–83

- ↑ "glucose." The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed.. 2015. Encyclopedia.com. 17 Nov. 2015 http://www.encyclopedia.com.

- 1 2 Encyclopedia of Food and Health. Academic Press. 2015. p. 239. ISBN 9780123849533.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2016-11-25.

- ↑ Thénard, Gay-Lussac, Biot, and Dumas (1838) "Rapport sur un mémoire de M. Péligiot, intitulé: Recherches sur la nature et les propriétés chimiques des sucres" (Report on a memoir of Mr. Péligiot, titled: Investigations on the nature and chemical properties of sugars), Comptes rendus …, 7 : 106–113. From page 109: "Il résulte des comparaisons faites par M. Péligot, que le sucre de raisin, celui d'amidon, celui de diabètes et celui de miel ont parfaitement la même composition et les mêmes propriétés, et constituent un seul corps que nous proposons d'appeler Glucose (1). … (1) γλευχος, moût, vin doux." It follows from the comparisons made by Mr. Péligot, that the sugar from grapes, that from starch, that from diabetes and that from honey have exactly the same composition and the same properties, and constitute a single substance that we propose to call glucose (1) … (1) γλευχος, must, sweet wine.

- 1 2 3 Bunn, H. F.; Higgins, P. J. (1981). "Reaction of monosaccharides with proteins: possible evolutionary significance". Science. 213: 222–224. doi:10.1126/science.12192669.

- ↑ High Blood Glucose and Diabetes Complications: The buildup of molecules known as AGEs may be the key link, American Diabetes Association, 2010, ISSN 0095-8301

- ↑ Essentials of Glycobiology. Ajit Varki (ed.) (2nd ed.). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories Press. ISBN 978-0-87969-770-9.

- ↑ "Chapter 3: Calculation of the Energy Content of Foods – Energy Conversion Factors", Food energy — methods of analysis and conversion factors, FAO Food and Nutrition Paper 77, Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization, 2003, ISBN 92-5-105014-7

- ↑ "Blood Brain Barrier and Cerebral Metabolism (Section 4, Chapter 11) Neuroscience Online: An Electronic Textbook for the Neurosciences | Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy - The University of Texas Medical School at Houston". Neuroscience.uth.tmc.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-25.

- ↑ Fairclough, Stephen H.; Houston, Kim (2004), "A metabolic measure of mental effort", Biol. Psychol., 66 (2): 177–90, PMID 15041139, doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2003.10.001

- ↑ Gailliot, Matthew T.; Baumeister, Roy F.; DeWall, C. Nathan; Plant, E. Ashby; Brewer, Lauren E.; Schmeichel, Brandon J.; Tice, Dianne M.; Maner, Jon K. (2007), "Self-Control Relies on Glucose as a Limited Energy Source: Willpower is More than a Metaphor", J. Personal. Soc. Psychol., 92 (2): 325–36, PMID 17279852, doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.325

- ↑ Gailliot, Matthew T.; Baumeister, Roy F. (2007), "The Physiology of Willpower: Linking Blood Glucose to Self-Control", Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev., 11 (4): 303–27, PMID 18453466, doi:10.1177/1088868307303030

- ↑ Masicampo, E. J.; Baumeister, Roy F. (2008), "Toward a Physiology of Dual-Process Reasoning and Judgment: Lemonade, Willpower, and Expensive Rule-Based Analysis", Psychol. Sci., 19 (3): 255–60, PMID 18315798, doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02077.x

- ↑ "Download Limit Exceeded". citeseerx.ist.psu.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-15.

- ↑ Bonadonna, Riccardo C; Bonora, Enzo; Del Prato, Stefano; Saccomani, Maria; Cobelli, Claudio; Natali, Andrea; Frascerra, Silvia; Pecori, Neda; Ferrannini, Eleuterio; Bier, Dennis; DeFronzo, Ralph A; Gulli, Giovanni (July 1996). "Roles of glucose transport and glucose phosphorylation in muscle insulin resistance of NIDDM" (PDF). Diabetes. 45 (7): 915–925. doi:10.2337/diab.45.7.915. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ↑ Medical Biochemistry at a Glance @Google books, Blackwell Publishing, 2006, p. 52, ISBN 978-1-4051-1322-9

- ↑ Medical Biochemistry at a Glance @Google books, Blackwell Publishing, 2006, p. 50, ISBN 978-1-4051-1322-9

- ↑ Estela, Carlos (2011) "Blood Glucose Levels," Undergraduate Journal of Mathematical Modeling: One + Two: Vol. 3: Iss. 2, Article 12.

- ↑ For methyl α-D-glucuopyranose at equilibrium, the ratio of molecules in each rotamer conformation is reported to be 57% gg, 38% gt, and 5% tg. See Kirschner, Karl N.; Woods, Robert J. (2001), "Solvent interactions determine carbohydrate conformation", Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 98 (19): 10541–45, PMC 58501

, PMID 11526221, doi:10.1073/pnas.191362798.

, PMID 11526221, doi:10.1073/pnas.191362798. - ↑ McMurry, John E. (1988), Organic Chemistry (2nd ed.), Brooks/Cole, p. 866, ISBN 0534079687.

- ↑ Juaristi, Eusebio; Cuevas, Gabriel (1995), The Anomeric Effect, CRC Press, pp. 9–10, ISBN 0-8493-8941-0

- 1 2 Fred W. Schenck "Glucose and Glucose-Containing Syrups" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2006, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi: 10.1002/14356007.a12_457.pub2

- ↑ Smith, Alison M.; Zeeman, Samuel C.; Smith, Steven M. (2005). "Starch Degradation". Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 56: 73–98. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144257.

- ↑ BeMiller, James N. & Whistler, Roy L., eds. (2009). Starch: Chemistry and Technology. Food Science and Technology (3rd ed.). New York: Academic Press. ISBN 008092655X. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ↑ "Carbohydrates and Blood Sugar". The Nutrition Source. 2013-08-05. Retrieved 2017-01-30 – via Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

- ↑ Ferraris, Ronaldo P. (2001), "Dietary and developmental regulation of intestinal sugar transport", Biochem. J., 360 (Pt 2): 265–76, PMC 1222226

, PMID 11716754, doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3600265

, PMID 11716754, doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3600265 - ↑ Marggraf (1747) "Experiences chimiques faites dans le dessein de tirer un veritable sucre de diverses plantes, qui croissent dans nos contrées" [Chemical experiments made with the intention of extracting real sugar from diverse plants that grow in our lands], Histoire de l'académie royale des sciences et belles-lettres de Berlin, pages 79-90. From page 90: "Les raisins secs, etant humectés d'une petite quantité d'eau, de maniere qu'ils mollissent, peuvent alors etre pilés, & le suc qu'on en exprime, etant depuré & épaissi, fournira une espece de Sucre." (Raisins, being moistened with a small quantity of water, in a way that they soften, can be then pressed, and the juice that is squeezed out, [after] being purified and thickened, will provide a sort of sugar.)

- ↑ Emil Fischer, Nobel Foundation, retrieved 2009-09-02

- ↑ Fraser-Reid, Bert, "van't Hoff's Glucose", Chem. Eng. News, 77 (39): 8

- ↑ Nassif, Houssam; Al-Ali, Hassan; Khuri, Sawsan; Keyrouz, Walid (2009). "Prediction of Protein-Glucose Binding Sites Using Support Vector Machines". Proteins: Structure, Function and Bioinformatics. 77 (7): 121–132. PMID 19415755. doi:10.1002/prot.22424.

Further reading

- Levine R (1986). "Monosaccharides in Health and Disease". Annu. Rev. Nutr. 6: 211–224. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- Röder PV, Wu B, Liu Y, Han W (2016). "Pancreatic Regulation of Glucose Homeostasis". Exp. Mol. Med. 48 (3, March): e219ff. PMC 4892884

. doi:10.1038/emm.2016.6.

. doi:10.1038/emm.2016.6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Glucose. |

.jpg)

.jpg)