Stanley Green

| Stanley Green | |

|---|---|

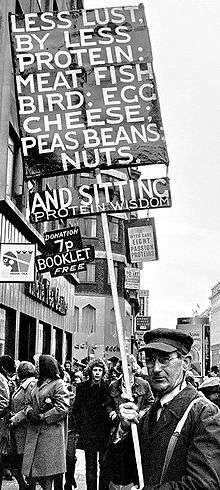

Stanley Green in Oxford Street, 1977 | |

| Born |

22 February 1915 Harringay, London |

| Died |

4 December 1993 (aged 78) Northolt, London |

| Known for | Dietary reform activism |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Military career | |

| Service/branch | Royal Navy |

| Years of service | 1938–1945 |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

Stanley Owen Green (22 February 1915 – 4 December 1993), known as the Protein Man, was a human billboard who became a well-known figure in central London in the latter half of the 20th century.[1]

Green patrolled Oxford Street in the West End for 25 years, from 1968 until 1993, with a placard recommending "protein wisdom", a low-protein diet that he said would dampen the libido and make people kinder. His 14-page pamphlet, Eight Passion Proteins with Care, went through 84 editions and sold 87,000 copies over 20 years.[2][3]

Green's campaign to suppress desire, as one commentator called it, was not always popular, but Londoners developed an affection for him. The Sunday Times interviewed him in 1985, and his "less passion from less protein" slogan was used by the fashion house Red or Dead.[4]

When he died at the age of 78, the Daily Telegraph, Guardian and Times published his obituary, and the Museum of London added his pamphlets and placards to their collection. In 2006 his biography was included in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.[1]

Early life

Green was born in Harringay, north London, the youngest of four sons of Richard Green, a clerk for a bottle stopper manufacturer, and his wife, May. He attended Wood Green School before joining the Royal Navy in 1938.[2]

According to Philip Carter in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Green shocked while in the navy by the obsession with sex.[2] "I was astonished when things were said quite openly—what a husband would say to his wife when home on leave," he told the Sunday Times' "A Life in the Day" column in 1985. "I've always been a moral sort of person."[5]

After leaving the Navy in September 1945, Green worked for the Fine Art Society. In March 1946, Carter writes, he failed the entrance exam for the University of London, then worked for Selfridges and the civil service, and as a storeman for Ealing Borough Council.[2] On two occasions he had lost jobs, he said, because he had refused to be dishonest.[6] In 1962 he held a job with the post office, then worked as a self-employed gardener until 1968 when he began his anti-protein campaign. He lived with his parents until they died, his father in 1966 and his mother the following year, after which he was given a council flat in Haydock Green, Northolt, north London.[2]

His mission

On the streets

.jpg)

Green began his mission in June 1968, at the age of 53, initially in Harrow on Saturdays, becoming a full-time human billboard six months later on Oxford Street. He cycled there from Northolt with a sandwich board attached to the bicycle, a journey of 12 miles (19 km) that could take up to two hours, until he was given a bus pass when he turned 65.[5]

He rose early, and after porridge for breakfast made bread that would rise while he was on patrol, ready for his evening meal. Otherwise his diet consisted of steamed vegetables and pulses, and a pound of apples a day. Lunch was prepared on a Bunsen burner and eaten at 2:30 in a "warm and secret place" near Oxford Street.[5]

From Monday to Saturday he walked up and down the street until 6:30 pm, reduced to four days a week from 1985. Saturday evenings were spent with the cinema crowds in Leicester Square.[2] He would go to bed at 12:30 am after saying a prayer. "Quite a good prayer, unselfish too", he told the Sunday Times. "It is a sort of acknowledgment of God, just in case there happens to be one."[5]

Peter Ackroyd wrote in London: The Biography that Green was for the most part ignored, becoming "a poignant symbol of the city's incuriosity and forgetfulness".[7] He was arrested for public obstruction twice, in 1980 and 1985.[2] "The injustice of it upsets me," he said, "because I'm doing such a good job." He took to wearing overalls to protect himself from spit, several times finding it on his hat at the end of the day.[5]

Writing

Sundays were spent at home producing Eight Passion Proteins on his printing press. Waldemar Januszczak described it as worthy of Heath Robinson, known for his cartoons of unlikely contraptions.[8] The "terrific sounds of thumping and crashing" caused trouble between Green and his neighbours.[9]

Noted for its eccentric typography, Eight Passion Proteins went through 84 editions,[3] 52 of them between 1973 and 1993.[10] Green sold 20 copies on weekdays and up to 50 on Saturdays (for 10 pence in 1980 and 12 pence 13 years later), a total of 87,000 copies by February 1993, according to Carter. He sent copies to several public figures, including five British prime ministers, the Prince of Wales, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and Pope Paul VI.[2]

The pamphlet argued that "those who do not have to work hard with their limbs, and those who are inclined to sit about" will "store up their protein for passion", making retirement, for example, a period of increased passion and marital discord.[11] He left several unpublished manuscripts, including a novel, Behind the Veil: More than Just a Tale; a 67-page text, Passion and Protein; and a 392-page edition of Eight Passion Proteins, which, Carter writes, was rejected by Oxford University Press in 1971.[2]

Posthumous recognition

Green enjoyed his local fame. The Sunday Times interviewed him in 1985 for its "A Life in the Day" feature, and some of his slogans, including "less passion from less protein" were used on dresses and t-shirts by the London fashion house Red or Dead.[lower-alpha 1]

When he died in 1993 at the age of 78, the Daily Telegraph, Guardian and Times all published obituaries.[2] His letters, diaries, pamphlets and placards were given to the Museum of London, which as of 2010 held 36 of the 84 editions of Eight Passion Proteins. With Care.[3][13] Other artefacts went to the Gunnersbury Park Museum.[2] His printing press was featured in Cornelia Parker's exhibition "The Maybe" (1995) at the Serpentine Gallery, along with Robert Maxwell's shoelaces, one of Winston Churchill's cigars, and Tilda Swinton in a glass box.[8] In 2006 he was given an entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.[1]

Two decades after his death Green was still remembered by writers and bloggers. The artist Alun Rowlands' documentary fiction, 3 Communiqués (2007), portrayed him as "trawl[ing] the city campaigning for the suppression of desire through diet".[14] Martin Gordon included a track about Green on his 2013 album, Include Me Out.[15]

.jpg) Near Oxford Street, 1974

Near Oxford Street, 1974%2C_London%2C_1983.jpg)

.jpg) Stanley Green exhibit, Museum of London

Stanley Green exhibit, Museum of London One of Green's placards, Museum of London

One of Green's placards, Museum of London Eight Passion Proteins with Care

Eight Passion Proteins with Care

Notes

- ↑ Red or Dead: "Mining the street for inspiration, Red or Dead printed Stanley Green’s placard and other selected texts from his message on dresses and t-shirts. Stanley Green was an eccentric English political activist well known along London’s Oxford Street for carrying his ‘Eat Less Protein’ placard. A replica of the placard itself accompanied some of the models wearing utilitarian suits. Every Red or Dead collection showed its ability to turn seamlessly from one source of inspiration to another of completely different origin."[12]

References

- 1 2 3 David McKie, "Pining for the boards", The Guardian, 21 July 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Philp Carter, "Green, Stanley Owen (1915–1993)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, May 2006. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/92286

- 1 2 3 Chris Broughton, "Curator's Choice: Cathy Ross of the Museum of London introduces The Protein Man's placard", Culture24, 3 June 2010.

- ↑ "Lives and times: Stanley Green", The Scotsman, 15 July 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stanley Green, "My own message to the streets", The Sunday Times Magazine, 14 April 1985.

- ↑ David Weeks and Jamie James, Eccentrics: A Study of Sanity and Strangeness, London: Random House, 1995, pp. 194–195.

- ↑ Pater Ackroyd, London, A Biography, Vintage, 2001, p. 189.

- 1 2 Waldemar Januszczak, "Making an exhibition of herself", The Sunday Times, 10 September 1995, cited in Susan M. Pearce and Paul Martin, The Collector's Voice: Critical Readings in the Practice of Collecting, Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2002, pp. 293–294.

- ↑ Tom Quinn, Ricky Leaver, Eccentric London, New Holland Publishers, 2008, p. 14.

- ↑ Matt Lake, Mark Moran, Mark Sceurman, Weird England, Sterling Publishing Company, 2007, p. 115.

- ↑ Stanley Green, Eight Passion Proteins, flaneur.org.uk, 2.

- ↑ "Story", Red or Dead.

- ↑ "Londoners", Museum of London.

- ↑ Alun Rowlands, 3 Communiqués, Book Works, 2007.

- ↑ Include Me Out, martingordon.de.

Further reading

- Cumming, Valerie; Merriman, Nick; Ross, Catherine. "The Protein Man", Museum of London, London: Scala Books, 1996.

- Donaldson, William. Brewer's Rogues, Villains, and Eccentrics, London: Cassell Reference, 2004.

- Lloyd, Felix. "I’m in training to be an old eccentric", London Evening Standard, 3 December 2008.

- Nevin, Charles. "The Third Leader: Street scenery", The Independent, 13 June 2006.

- Ross, C. "The scourge of sex and nuts and sitting", The Oldie, March 1997.

- The London Traveler. "The Less Protein Man – a sight of old London". Archived 31 January 2011.

- Truss, Lynne. "Stanley Green", The Times (obituary), 25 January 1994.

- Weeks, David Joseph with Ward, Kate. Eccentrics: The Scientific Investigation, Stirling: Stirling University Press, 1988.

- Wicks, Ben. "Come on up and see my collection of passion fruit", The Toronto Star, 8 March 1986.

- Willis, David. "A Consuming Passion" (obituary), The Guardian, 26 January 1994.