Saint Eustace

| Saint Eustace and companions | |

|---|---|

|

Greek Orthodox icon of St. Eustathios | |

| Martyrs | |

| Died | 118 AD |

| Venerated in | Anglican Church; Roman Catholic Church; Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Feast | September 20 (Western Christianity, Eastern Orthodoxy) |

| Attributes | bull; crucifix; horn; stag; oven |

| Patronage | against fire; difficult situations; fire prevention; firefighters; hunters; hunting; huntsmen; Madrid; torture victims; trappers |

Saint Eustace, also known as Eustachius or Eustathius in Latin,[1] St. Esthak in India, or Sh. Staka in Albania, is revered as a Christian martyr and soldier saint. Legend places him in the 2nd century AD. A martyr of that name is venerated as a saint in the Anglican Church.[2] He is commemorated by the Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church on September 20.

Biography

According to tradition, [3] prior to his conversion to Christianity Eustace was a Roman general named Placidus, who served the emperor Trajan. While hunting a stag in Tivoli near Rome, Placidus saw a vision of a crucifix lodged between the stag's antlers.[4] He was immediately converted, had himself and his family baptized, and changed his name to Eustace (Greek: Ευστάθιος (Eustáthios), "well stable", or Ευστάχιος (Eustáchios), "fruitful/rich grain").

A series of calamities followed to test his faith: his wealth was stolen; his servants died of a plague; when the family took a sea-voyage, the ship's captain kidnapped Eustace's wife Theopista; and as Eustace crossed a river with his two sons Agapius and Theopistus, the children were taken away by a wolf and a lion. Like Job, Eustace lamented but did not lose his faith.

He was then quickly restored to his former prestige and reunited with his family. There is a tradition that when he demonstrated his new faith by refusing to make a pagan sacrifice, the emperor Hadrian condemned Eustace, his wife, and his sons to be roasted to death inside a bronze statue of a bull or an ox,[5] in the year AD 118. However, the Catholic Church rejects this story as "completely false".[6]

Variants

The opening part of this tradition, up to St. Eustace's martyrdom, is a variant of a popular tale in chivalric romance: "the Man Tried By Fate".[7] Except for an exemplum in Gesta Romanorum,[8] all such tales are highly developed romances, such as Sir Isumbras.[9] A distant Indian origin for elements in the Eustace legend has been proposed.[10]

Diffusion of his veneration

The veneration of Eustace originated in the Eastern Orthodox Church. In the West, an early-medieval church dedicated to him that existed in Rome is mentioned in a letter of Pope Gregory II (731-741).[11] His iconography may have passed to the 12th-century West, before which time European examples are scarce, in psalters, where the vision of Eustace, kneeling before a stag, illustrated Psalm 96, ii-12: "Light is risen to the just..."[12] An early depiction of Eustace, the earliest one noted in the Duchy of Burgundy, is carved on a Romanesque capital at Vézelay Abbey.[13] Abbot Suger mentions the first relics of Eustace in Europe, at an altar in the royal Basilica of St Denis;[14] Philip Augustus of France rededicated the church of Saint Agnès, Paris, which became Saint-Eustache (rebuilt in the 16th-17th centuries). The story of Eustace was popularized in Jacobus de Voragine's "Golden Legend" (c. 1260). Scenes from the story, especially of Eustace kneeling before the stag, then became popular subjects of medieval religious art: examples include a wall painting at Canterbury Cathedral and stained glass windows at the Cathedral of Chartres.

As with many early saints, there is no evidence for Eustace's existence, even as a martyr.[15] Elements of his story have been re-attributed to other saints, notably the Belgian Saint Hubert.

Saint Eustace's feast day in the Roman Catholic Church is September 20, as is indicated in the Roman Martyrology.[6] The celebration of Saint Eustace and his companions was included in the Roman Calendar from the twelfth century until 1969, when it was removed because of the completely fabulous character of the saint's Acta,[6][16] resulting in a lack of sure knowledge about them. However, his feast is still observed by Roman Catholics who follow the pre-1970 Roman Calendar.

Modern connections

Eustace became known as a patron saint of hunters and firefighters, and also of anyone facing adversity; he was traditionally included among the Fourteen Holy Helpers.[17] He is one of the patron saints of Madrid, Spain. The island of Sint Eustatius in the Caribbean Netherlands is named after him.

The d'Afflitto, one of the oldest princely families in Italy, claim to be direct descendants of Saint Eustace.

The novels "The Herb of Grace" (US title: Pilgrim's Inn) (1948) by British author Elizabeth Goudge, and Riddley Walker (1980) by American author Russell Hoban, incorporate the legend into their plot. It has also inspired the film Imagination.

The saint's cross-and-stag symbol is featured on bottles of Jägermeister, a German alcoholic digestif. This is related to his status as patron of hunters; a Jägermeister was a senior foresters and gamekeeper in the German civil service until 1934, prior to the drink's introduction in 1935.

Saint Eustace has a church dedicated to him in the southern part of India, in a village named Mittatharkulam, near Tiruneveli district in Tamil Nadu. He is called Saint Esthak in this part of the world.

Saint Eustace is honored in County Kildare, Ireland. There is a church dedicated to him on the campus of Newbridge College in Newbridge, County Kildare, and the schools' logo and motto is influenced by the vision of Saint Eustace; a nearby village is named Ballymore Eustace.

Sant'Eustachio is also honoured in Tocco da Casauria, a town in the Province of Pescara in the Abruzzo region of central Italy. The town's church, built in the twelfth century, was dedicated to Saint Eustace. It was rebuilt after being partially destroyed by an earthquake in 1706.[18]

See also

- Saint-Eustache, Quebec

- Sint Eustatius, a Caribbean Netherlands island named after Saint Eustace

- Imagination, a 2007 film inspired by Saint Eustace

- Hubertus, another saint with a similar legend

- Saint-Eustache, Paris, a Parisian church bearing his name

References

- ↑ "Given name Eustace". Behind the Name. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

English form of EUSTACHIUS or EUSTATHIUS, two names of Greek origin which have been conflated in the post-classical period.

- ↑ We find on the authority of Mr. Parker in his work entitled the Calendar of the Anglican Church, and also in a work called Emblems of Saints, that St. Eustace was also sometimes represented carrying a horn (1878). The Archaeological journal. Longman, Brown, Green, and Longman. p. 281. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ↑ Eustace's Vita is edited in the Acta Sanctorum, September 6:124.

- ↑ The image of the crucifix lodged between the antlers of a stag and its justification in a hunting episode were later transferred to the hagiography of Saint Hubertus (first Bishop of Liège).

- ↑ "Saints & Martyrs", Columbia University

- 1 2 3 "Martyrologium Romanum" (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2001 ISBN 88-209-7210-7)

- ↑ Laura A. Hibbard, Medieval Romance in England p5 (New York: Burt Franklin) 1963

- ↑ Wikisource text of the Gesta Romanorum story.

- ↑ Hibbard, p.3.

- ↑ Engels, O., "Die hagiographischen texte der Papst Gelasius II' in der Überlieferung der Eustachius-, Erasmus- und Hypolistuslegende", Historisches Jahrbuch 76 (1956, noted by Ambrose 2006.

- ↑ Krautheimer, R., Corpus basilicarum christianarum Romae (1940) vol. I:216f and Krautheimer, Rome: Profile of a City 1980:80f, 252, 271.

- ↑ Kirk Thomas Ambrose, The Nave Sculpture of Vézelay: The Art of Monastic Viewing (Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies) 2006:45 gives examples.

- ↑ Ambrose 2006:45.

- ↑ The Eustace venerated at Saint-Denis may have been Eustace of Luxeuil, the second abbot of Luxueil, from 611.

- ↑ Hibbard, p.4.

- ↑ "Calendarium Romanum" (Libreria Editrice Vaticana), p. 139

- ↑ Newton, William. "St. Eustace", Victoria and Albert Museum

- ↑ http://www.toccodacasauria.com/products/piazza-e-chiesa-di-sant-eustachio/

Sources

- Hibbard, Laura A., Medieval Romance in England, New York, Burt Franklin, 1963

Gallery

Saint Eustace, from a 13th-century English manuscript.

Saint Eustace, from a 13th-century English manuscript. On a wing of the Paumgartner altarpiece, Albrecht Dürer painted Lukas Paumgartner with the banner of his patron, St. Eustace, in the contemporary armor of a Landsknecht.

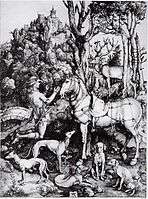

On a wing of the Paumgartner altarpiece, Albrecht Dürer painted Lukas Paumgartner with the banner of his patron, St. Eustace, in the contemporary armor of a Landsknecht. Saint Eustachius, an engraving by Albrecht Dürer, ca. 1501. As in the Pisanello above, he kneels before a stag with a cross in its antlers, surrounded by dogs, including greyhounds.

Saint Eustachius, an engraving by Albrecht Dürer, ca. 1501. As in the Pisanello above, he kneels before a stag with a cross in its antlers, surrounded by dogs, including greyhounds. Saint Eustace icon, an example of the Cretan School.

Saint Eustace icon, an example of the Cretan School. Francesco Ferdinandi, The Martyrdom of St. Eustace. Located behind the main altar at the Church of Sant'Eustachio, Rome, this painting follows the narrative in the Golden Legend: For refusing to sacrifice to the gods, St. Eustace and his wife and sons are to be enclosed in a Brazen bull which will be heated until they die.

Francesco Ferdinandi, The Martyrdom of St. Eustace. Located behind the main altar at the Church of Sant'Eustachio, Rome, this painting follows the narrative in the Golden Legend: For refusing to sacrifice to the gods, St. Eustace and his wife and sons are to be enclosed in a Brazen bull which will be heated until they die. The stag-and-cross symbol of St. Eustace sits atop his church in Rome.

The stag-and-cross symbol of St. Eustace sits atop his church in Rome. The stag-and-cross symbol of St. Eustace as appearing on a bottle of Jägermeister digestif.

The stag-and-cross symbol of St. Eustace as appearing on a bottle of Jägermeister digestif.

External links

- Patron Saints: Saint Eustachius

- Here Followeth the Life of St. Eustace in Caxton's translation of the Golden Legend

- Saint Eustace at the Christian Iconography web site

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Sts. Eustachius and Companions". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Sts. Eustachius and Companions". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.- The 'Life of St Eustace' window at Chartres Cathedral