St Clement's, Eastcheap

| St Clement Eastcheap | |

|---|---|

|

St Clement Eastcheap Clements Lane, London | |

St Clement's Church, October 2006 | |

| Location | Clement's Lane, City of London |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Website | Official website |

| History | |

| Founded | pre. 1067 |

| Dedicated | 1687 |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Grade I listed building |

| Architect(s) | Sir Christopher Wren |

| Years built | 1683 (begun) |

| Administration | |

| Parish | St Clement, Eastcheap |

| Diocese | London |

| Division | Archdeaconry of London |

| Subdivision | City Deanery |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Bishop of London |

| Priest(s) | Interregnum |

| Archdeacon | Archdeacon of London |

| Laity | |

| Organist(s) | Ian Shaw |

| Chapter clerk | Dickon Love |

| Churchwarden(s) | John Holt and George Andrews |

St Clement Eastcheap is a Church of England parish church in Candlewick Ward of the City of London. It is located on Clement's Lane, off King William Street and close to London Bridge and the River Thames.[1]

Clement was a disciple of St Peter the Apostle and was ordained as Bishop of Rome in the year 93 AD. By legend, Clement was martyred by being tied to an anchor and thrown into the Black Sea, which led to his adoption as a patron saint of sailors. The dedication to St Clement is unusual in London, with only one other ancient church there dedicated to this saint, namely St Clement Danes, Westminster. It is also located a little north of the Thames, but further west from Eastcheap and outside the old City boundary, just beyond the Temple Bar on the Strand.

History

Medieval period

Eastcheap was one of the main streets of medieval London. The name 'Eastcheap' derives from the Saxon word 'cheap', meaning a market, and Eastcheap was so called to distinguish it from Westcheap, later to become Cheapside. The southern end of Clement's Lane opened onto Eastcheap until the 1880s when the construction of King William Street separated Clement's Lane from Eastcheap, which still remains nearby as a street.

.gif)

The church's dedication to a Roman patron saint of sailors, the martyr Bishop Clement, coupled with its location near to what were historically the bustling wharves of Roman London, hints at a much earlier Roman origin. Indeed, Roman remains were once found in Clement's Lane, comprising walls 3 feet thick and made of flints at a depth of 12–15 feet together with tessellated pavements.[2]

A charter of 1067 given by William I (1028–87) to Westminster Abbey mentions a church of St. Clement, which is possibly St. Clement Eastcheap, but the earliest definite reference to the church is found in a deed written in the reign of Henry III (1207–72), which mentions 'St Clement Candlewickstrate'. Other early documents refer to the church as "St Clement in Candlewystrate", 'St Clement the Little by Estchepe' and 'St Clement in Lumbard Street'. Until the dissolution of the monasteries – during the reign of Henry VIII – the parish was in the 'gift' of the Abbot of Westminster, then patronage of the parish passed to the Bishop of London. Now the patronage alternates with the appointment of each successive new parish priest (Rector), between the Bishop of London and the Dean and Chapter of St Paul's.

According to the London historian John Strype (1643–1737) St. Clement's church was repaired and beautified in 1630 and 1633.[3]

Destruction and rebuilding

In 1666 the church was destroyed by the Great Fire of London, and then rebuilt in the 1680s. According to Strype the rebuilt church was designed by Sir Christopher Wren and this would seem to be confirmed by the fact that in the parish account for 1685 there is the following item: To one third of a hogshead of wine, given to Sir Christopher Wren, £4 2s.[4]

In 1670, during the rebuilding of London that followed the fire, the parish was combined with that of St Martin Orgar, which lay on the south side of Eastcheap. At the same time the City planners sought to appropriate a strip of land from the west of St Clement's property to widen Clement's Lane. This led to a dispute with the parish authorities, who claimed that the proposed plan left too little room to accommodate the families of the newly combined parishes. The matter was resolved by permitting the addition of a 14 ft. building plot, formerly occupied by the churchyard, to the east of the church. It was not until 1683, however, that building of the church began, and was completed in 1687 at a total cost of £4,365.[5]

Although nearby St Martin Orgar had been left in ruins by the Great Fire, the tower survived and, following the unification of the parish with St Clement's, the St Martin's site was used by French Huguenots who restored the tower and worshiped there until 1820. Later in the decade the ruins of the body of St Martin's church were removed to make way for the widening of Cannon Street, but the tower remained until 1851 when it was taken down, and – curiously – replaced with a new tower. The new tower served as a rectory for St. Clement Eastcheap until it was sold and converted into offices in the 1970s; it still survives on the present-day Martin Lane.

19th century

In May 1840 Edward John Carlos wrote in The Gentleman's Magazine, protesting about the proposed demolition of St Bartholomew-by-the-Exchange and St. Benet Fink, following a fire in 1838 that had razed the Royal Exchange and damaged those two churches. In his article, Carlos referred to earlier plans to reduce the number of City churches, from which we learn that in the 1830s St Clement's had been under threat of demolition.

The sweeping design of destroying a number of City churches was mediated in … 1834, and for the time arrested by the resolute opposition to the measure in the instance of the first church marked out for sacrifice, St. Clement Eastcheap, it may be feared is at length coming into full operation, not, indeed in the open manner in which it was displayed at that period, but in an insidious and more secure mode of procedure.[6]

While St Clement's was spared, the 19th century saw many other City churches being destroyed, particularly following the Union of Benefices Act (1860), which sought to speed-up the reduction in the number of City parishes as a response to rapidly declining congregations; the result of the resident population moving in ever larger numbers from cramped City conditions to the more spacious suburbs.

In 1872 William Butterfield, a prominent architect of the gothic-revival, substantially renovated St. Clement's to conform with the contemporary Anglican 'High Church' taste.[7] The renovation involved removing the galleries; replacing the 17th-century plain windows with stained glass; dividing the reredos into three pieces and placing the two wings on the side walls; dismantling the woodwork to build new pews; laying down polychrome tiles on the floor and moving the organ into the aisle.

20th century

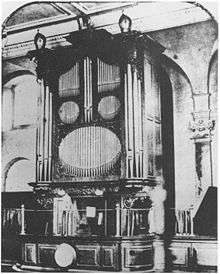

In 1933 the architect Sir Ninian Comper revised Butterfield's layout, moving the organ to its original position on the west wall and reassembling the reredos behind the altar, although before he did so, he had the reredos painted with figures in blue and gold.

St. Clement's suffered minor damage from bombing by German aircraft during the London Blitz in 1940 during the Second World War. The damage was repaired in 1949–50, and in 1968 the church was again redecorated.

Present

Today St Clement's holds weekly services and, from 1998 to 2011, it was the base of The Players of St Peter, an amateur theatre company devoted to performing medieval mystery plays in the church, around early December each year.[8] The Players are now based at the church of St George in the East.

A number of charities have their administrative offices at St Clement's. The Cure Parkinson's Trust was based here for several years but is now at 120 Baker Street, London.

"Oranges and Lemons"

St Clement Eastcheap considers itself to be the church referred to in the nursery rhyme that begins "Oranges and lemons / Say the bells of St Clement's". So too does St Clement Danes Church, Westminster, whose bells ring out the traditional tune of the nursery rhyme three times a day.

There is a canard that the earliest mention of the rhyme occurs in Wynkyn de Worde's "The demaundes joyous" printed in 1511.[9] This small volume consists entirely of riddles and makes no allusion to bells, St. Clement or any other church.

According to Iona and Peter Opie,[10] the earliest record of the rhyme only dates to c.1744, although there is a square dance (without words) called 'Oranges and Limons' in the 3rd edition of John Playford's The English Dancing Master, published in 1665.

St Clement Eastcheap's claim is based on the assertion that it was close to the wharf where citrus fruit was unloaded. Yet, a perusal of a map of London shows that there were many churches, even after the Fire, that were closer to the Thames than St. Clement's (St. George Botolph Lane, St Magnus the Martyr, St. Michael, Crooked Lane, St Martin Orgar, St Mary-at-Hill, All Hallows the Great. All these would have been passed by a load of oranges and lemons making its way to Leadenhall Market, the nearest market where citrus fruit was sold, passing several more churches on the way. Thus, it would appear that the name of St. Clements was selected by the rhymer simply for its consonance with the word ‘lemons’, and it now seems more likely that the melody called ‘Oranges and Limons’ predates the rhyme itself.

Building

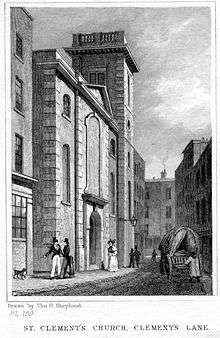

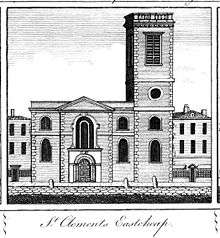

St. Clement Eastcheap has an irregular plan. The nave is approximately rectangular, but the south aisle is severely tapered. The ceiling is divided into panels, the centre one being a large oval band of fruit and flowers. The main façade is on the west, on Clement's Lane, and comprises four bays. The main bay has a blocked pedimented round-headed window over the door. This is flanked by matching bays with two levels of windows. The tower to the south west forms the fourth bay. This is a simple square tower, with a parapet, but no spire. Each bay has stone quoins and is stuccoed, except for the upper levels of the tower where the brick is exposed.

A small churchyard remains to the east of St. Clement's hemmed-in by the backs of office buildings and contains tombstones whose inscriptions have, over time, become illegible. The churchyard is approached by a narrow alley along the church's north wall, at the entrance of which is a memorial plaque to Dositej Obradović, a Serbian scholar who lived next to the church.[11]

In July 1645, so it is said, the poet John Milton was reconciled with his estranged wife Mary Powell, in the house of a Mrs Weber, a widow, in St Clement's churchyard where Mary was then lodging. Milton's description in Paradise Lost of the reconciliation of Adam and Eve draws, apparently, on the real life reconciliation between Milton and his wife.[12]

She, not repulsed, with tears that ceased not flowing

And tresses all disordered, at his feet

Fell humble, and, embracing them, besought

His peace.

[...]

Soon his heart relented

Towards her, his life so late, and sole delight,

Now to his feet submissive in distress.

The church was designated a Grade I listed building on 4 January 1950.[13]

Organ

The present organ's oak case is the same one made to enclose the organ that was built for St Clement's in 1696, probably by Renatus Harris who maintained the instrument until 1704.[14] While the case has remained largely intact, the organ itself has been variously rebuilt and restored; in 1704 by Christian Smith, and in 1711 by Abraham Jordan (c.1666–1716)—who it is thought added the swell organ to the two manual instrument. From 1838 the organ was in the care of Messrs Gray and Davison, who in 1872—as part of the renovation of the building—moved the organ from the west gallery to the south aisle. Care of the organ was transferred to Henry Wedlake that same year. In 1889 he rebuilt the instrument. Further work was undertaken in 1926 by Messrs J. W. Walker, and in 1936 by Messrs Hill, Norman and Beard, whew the instrument was moved back to an approximation of its original west-end location. The same company overhauled the organ in 1946, and in 1971 made 'neo-baroque' tonal revisions, which remain to this day. The instrument was last cleaned and repaired in 2004 by Colin Jilks of Sittingbourne, Kent.

Organists

The first known organist:

- Henry Lightindollar (died 1702), appeared in the parish records in 1699. Successive organists were as follows:

- William Gorton, a member of the King's Music (appt. 1702, died 1711)

- Edward Purcell, son of Henry Purcell (born 1689, appt. 1711, died 1740, and buried in St Clements "near the gallery door" – Parish Burial Register, 4 July 1740)

- Edward Henry Purcell, Edward's son (appt.1740, died 1765, and also buried in the church "by the organ gallery" – Parish Burial Register, 5 August 1765)

- Jonathan Battishill (born 1738, appt. 1765, died 1801)

- Thomas Bartholomew (appt. 1802, died 1819)

- William Bradley (appt. 1819, res. 1828)

- John Whitaker, a City music publisher, (appt. 1828, died 1847)

- John Joff, promoted from assistant organist (appt. 1847, died 1885).[15]

The current organist (September 2008) is Ian Shaw.

Furnishings

The altar, with cherubs for legs, dates from the 17th century, as does the reredos, which was decorated during the 1930s restoration of the building in a style reminiscent of Simone Martini. The outer panels depict the Annunciation while the central panel shows St. Clement and St. Martin of Tours, (the dedicatee of St. Martin Orgar).

The pulpit also dates from the 17th-century, and is made from Norwegian oak, topped with an hexagonal sounding board, with a dancing cherub on each corner.

Surviving from the 1872 Butterfield renovation are the polychrome floor and three stained-glass clerestory windows on the north wall. The windows were made by W. G. Taylor, and installed c.1887 during the last phase of Butterfield's work.[16] The windows show SS. Andrew, James (major), James (minor), Peter, Mathias, and Thomas.[17]

While the marble font can be seen, its wooden cover is not always on public display. The cover's ornate decoration, a carved dove holding an olive branch surrounded with gilded flames, so delighted William Gladstone, it is said, that he took his grandchildren to see it.

Clergy

Thomas Fuller (1608–61), then living in London, preached a series of sermons at St Clement's in 1647.

The diarist John Evelyn heard John Pearson (1613–86), later to be Bishop of Chester, preaching at St Clement's where he was the weekly preacher from 1654. His sermons there later became his An Exposition of the Creed (1659), which he dedicated "to the right worshipful and well-beloved, the parishioners of St. Clement's, Eastcheap."

One of the rectors of St. Clement's, Benjamin Stone, who had been presented to the living by Bishop Juxon, being deemed "too Popish" by Oliver Cromwell, was imprisoned for some time at Crosby Hall. From there he was sent to Plymouth where, after paying a fine of £60, he obtained his liberty. Stone recovered his benefice on the restoration of Charles II but died five years after. (Thornbury, volume 1)

In this church Josias Alsopp, who had succeeded Stone as rector in the early Restoration years of the 17th century, was heard preaching by Samuel Pepys who noted the following in his diary for 24 November 1661:

Up early, and by appointment to St. Clement lanes to church, and there to meet Captain Cocke, who had often commended Mr. Alsopp, their minister, to me, who is indeed an able man, but as all things else did not come up to my expectations. His text was that all good and perfect gifts are from above.

Among the mural tablets in the church are three which have been erected at the cost of the parishioners, commemorative of the Rev. Thomas Green, curate twenty-seven years, who died in 1734; the Rev. John Farrer, Rector, who died in 1820; and the Rev. W. Valentine Ireson, who was lecturer of the united parishes for thirty years and died in 1822.[4]

Memorial

Immediately next to the church in Clement's Lane is a memorial stone to Dositej Obradović (1742–1811), a Serbian statesman and man of letters who became Serbia's first Education Minister. He stayed in a house here in 1784. His name here is anglicised to Dositey Obradovich.

See also

References

- ↑ See an aerial view at Wikimapia < http://www.wikimapia.org/#lat=51.511337&lon=-0.086877&z=20&l=0&m=h&v=2 >, accessed 1 August 2008

- ↑ Harben, H. A. (1918) A Dictionary of London London: Jenkins

- ↑

- Strype, John (1720) A survey of the Cities of London and Westminster ... brought down from the year 1633 ... to the present time London: Churchill et al.

- 1 2 Thornbury, Walter (1878) 'Bartholomew Lane and Lombard Street' in Old and New London: Volume 1 pp. 522–530. British History Online (University of London) < http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=45063 > accessed 3 November 2007

- ↑ Bradley, Simon & Pevsner, Nikolaus (1997) London (vol. 1, The City of London). Series: The Buildings of England. London: Penguin

- ↑ "The Churches of St Bartholomew-by-the-Exchange and St. Benet Fink, London". The Gentleman's Magazine: 461. May 1840.

- ↑ "The Visitors Guide to the City of London Churches" Tucker,T: London, Friends of the City Churches, 2006 ISBN 0-9553945-0-3

- ↑ The Players of St Peter, official web sitesite < http://www.theplayersofstpeter.org.uk/>, accessed 1 August 2008; The Players of St Peter: the alternative menu to the official site and the official menu to the alternative site < http://www.rhaworth.myby.co.uk/pofstp/proglist.htm >, accessed 1 August 2008.

- ↑ de Worde, Wynkyn (1511) The Demaundes Joyous (1971 facsimile edition with notes by John Wardroper) London: Gordon Fraser

- ↑

- Opie, Iona and Opie, Peter (eds.) (1997) The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes Oxford: Oxford University Press

- ↑

'Candelwick Ward' in London Burial Grounds < http://www.doubleo.fsnet.co.uk/bgcandlewick.htm >, accessed 31 December 2007 - ↑ Thornbury, Walter (1878)'Aldersgate Street and St Martin-le-Grand'in Old and New London: Volume 2 pp. 208–228. British History Online (University of London) < http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=45092 > accessed 3 November 2007.

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from image database (199374)". Images of England. accessed 23 January 2009

- ↑ All the information in this section is based on: Gray. G. W. (2008) 'St Clement Eastcheap' in The Organ Club Journal 2008/1 47

- ↑ Dawe, Donovan (1983) Organs and Organists of the City of London 1666–1850 Padstow: Dawe; Pearce,C.W.(1909) Notes on Old City Churches: their organs, organists and musical associations London, Winthrop Rogers Ltd

- ↑ Gray. G. W. (2008) 'St Clement Eastcheap' in The Organ Club Journal 2008/1 47

- ↑ Church Stained Glass Windows recorded by Robert Eberhard – updated October 2007 <http://www.stainedglassrecords.org/>, accessed 6 September 2008

- Betjeman, J (1967) The City of London Churches Andover: Pitkin (ISBN 0-85372-112-2)

- Blatch, Mervyn (1995) A Guide to London's Churches London: Constable

- Clout, Hugh (ed.) (1999) The Times History of London London: Times Books

- Cobb, Gerald (1977) London City Churches London: Batsford

- Heulin, Gordon (1996) Vanished Churches of the City of London London: Guildhall Library Publications

- Hibbert,C;Weinreb,D;Keay:London Encyclopaedia London Pan Macmillan 1983 (rev2008)

- Jeffery, Paul (1996) The City Churches of Sir Christopher Wren London: Hambledon

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St Clement Eastcheap. |

- Parish Information from the Diocese of London Directory

- Services at St Clement Eastcheap from Friends of the City Churches

- Inhabitants of London in 1638 St. Clement’s, Eastcheap, edited from Ms.272 in Lambeth Palace Library by T. C. Dale (1931)

- Four Shillings In The Pound Aid 1693–1694, City of London, Candlewick Ward, St Clements Eastcheap Precinct, data created by Derek Keene, Peter Earle, Craig Spence and Janet Barnes (1992)

- Players of St Peter, medieval mystery plays in the City of London

- The Foundation for Public Service Interpreting

- The Cure Parkinson's Trust