Sri Lankan Moors

| இலங்கைச் சோனகர் ලංකා යෝනක | |

|---|---|

20th century Sri Lankan Moors | |

| Total population | |

|

1,869,820[1] (9.2% of the Sri Lankan population) (2012)[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Province | |

| 569,182 | |

| 450,505 | |

| 260,380 | |

| 252,694 | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (mostly Sunni) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

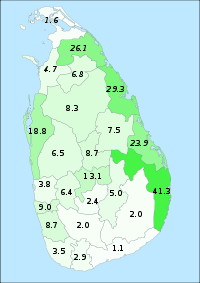

Sri Lankan Moors (Tamil: இலங்கைச் சோனகர்; Sinhalese: ලංකා යෝනක Lanka Yonaka); formerly Ceylon Moors; colloquially referred to as Muslims) are the third largest ethnic group in Sri Lanka, comprising 9.23% of the country's total population. They are native speakers of the Tamil language[3][4] and predominantly followers of Islam. The Tamil term for Muslims in Sri Lanka is சோனகர் (Sonakar), சோனர் (Sonar) or சோனி (Sooni) probably derived from Sunni.[5] While some sources describe them as a subset of the Tamil people who had adopted Islam as their religion and spoke Tamil as their mother tongue, which they continue to do,[3][5][6][7][8] other sources trace their ancestry to Arab traders (Moors) who settled in Sri Lanka some time between the 8th and 15th centuries.[9][10][11][12] Moors today use Tamil as their primary language, with influence from Arabic.[6] Those in the Southern, Western and Central regions of the country are also fluent in Sinhalese, the majority language of Sri Lanka. The population of Moors are the highest in the Ampara, Colombo, Kandy and Trincomalee districts.

History

Origins theories

Tamil origin

Throughout history, the Tamils of Sri Lanka have tried to classify the Sri Lankan Moors as belonging to the Tamil ethnic group.[11] Their view holds that the Sri Lankan Moors were simply Tamil converts to Islam. The claim that the Moors were the progeny of the original Arab settlers, might hold good for a few families but not for the entire bulk of the community.[5] This is evidenced by the fact that, the Moors's Islamic Cultural Home, Colombo were unsuccessful in digging up the genealogical history of Muslim families with Arab descent, in any great numbers. I.L.M. Abdul Azeez (of the organization) seemed to have accepted the idea, when he observed that:

It may be safely argued that, the number of original settlers was not even more than a hundred.

Another theory claims, Sri Lankan Moors are not a distinct or self-defined people and the word (Moors) did not exist in Sri Lanka before the arrival of the Portuguese colonists.[13] The Portuguese named the Muslims in India and Sri Lanka after the Muslim Moors they met in Iberia.[14] Moreover, the term 'Moor' referred to only their religion and was no reflection on their origin.[5]

The concept of Arab descent was thus, invented just to keep the community away from the Tamils and this 'separate identity' intended to check the latter's demand for the separate state Tamil Eelam and to flare up hostilities between the two groups in the broader Tamil-Sinhalese conflict.[5][7][8]

Arab origin

Another view suggests that the Arab traders, however, adopted the Tamil language only after settling in Sri Lanka.[12] This version claims that the features of Sri Lankan Moors as different from that of Tamils; they commonly have lighter skin tone and hair color. The cultural practices of the Moors also vary significantly from the other communities on the island. Thus, most scholars classify the Sri Lankan Moors and Tamils as two distinct ethnic groups, who speak the same language.[12] This view is dominantly held by the Sinhalese favoring section of the Moors as well as the Sri Lankan government which lists the Moors as a separate ethnic community.[5] A study on genetic variation indicates, a genetic relationship between Arabs and the Moors.[10]

Mixer of Tamil and Arabs

Another theory claims that the Sri Lankan Moors are not proto-Dravidian but carry the genes of both Arab and Tamil due to centuries of miscegenation.

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1881 | 184,500 | — |

| 1891 | 197,200 | +6.9% |

| 1901 | 228,000 | +15.6% |

| 1911 | 233,900 | +2.6% |

| 1921 | 251,900 | +7.7% |

| 1931 | 289,600 | +15.0% |

| 1946 | 373,600 | +29.0% |

| 1953 | 464,000 | +24.2% |

| 1963 | 626,800 | +35.1% |

| 1971 | 828,300 | +32.1% |

| 1981 | 1,046,900 | +26.4% |

| 1989 (est.) | 1,249,000 | +19.3% |

| 2001 | 1,339,300 | +7.2% |

| 2012 | 1,869,820 | +39.6% |

| Prior to 1911, Indian Moors were included with Sri Lankan Moors. Source:Department of Census & Statistics[15] Data is based on Sri Lankan Government Census. | ||

Culture

The Sri Lankan Moors have been strongly shaped by Islamic culture, with many customs and practices according to Islamic law. While preserving many of their ancestral customs, the Moors have also adopted several South Asian practices.[16]

Language

Tamil is stated to be the mother tongue of more than 99% of the community. Moorish Tamil bears the influence of Arabic.[6] Furthermore, the Moors like their counterparts[4][17] in Tamil Nadu, use the Arwi which is a written register of the Tamil language with the use of the Arabic alphabet.[18] The Arwi alphabet is unique to the Muslims of Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka, hinting at erstwhile close relations between the Tamil Muslims across the two territories.[4]

Religious sermons are delivered in Tamil even in regions where Tamil is not the majority language. Islamic Tamil literature has a thousand-year heritage.[3]

Customs

The Moors practice several customs and beliefs, which they closely share with the Arab, Sri Lankan Tamils and Sinhalese People. Tamil and Sinhala customs such as wearing the Thaali or eating Kiribath were widely prevalent among the Moors. Arab customs such as congregational eating using a large shared plate called the 'sahn' and wearing of the North African fez during marriage ceremonies feed to the view that Moors are of mixed Sinhalease, Tamil and Arab heritage.[3][5]

There have been a growing trend amongst Moors to rediscover their Arab heritage and reinstating the Arab customs that are the norm amongst Arabs in Middle East and North Africa. These include replacing the sari and other traditional clothing associated with Sinhalese and Tamil culture in favour of the abaya and hijab by the women as well as increased interest in learning arabic and appetite for Arab food by opening restaurants and takeaways that serve Arab food such as shawarma and Arab bread.

See also

References

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

- ↑ "A2 : Population by ethnic group according to districts, 2012". Census of Population & Housing, 2011. Department of Census & Statistics, Sri Lanka.

- ↑ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ce.html

- 1 2 3 4 "Sri Lankan Muslims Are Low Caste Tamil Hindu Converts Not Arab Descendants". Colombo Telegraph. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 Torsten Tschacher (2001). Islam in Tamilnadu: Varia. (Südasienwissenschaftliche Arbeitsblätter 2.) Halle: Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg. ISBN 3-86010-627-9. (Online versions available on the websites of the university libraries at Heidelberg and Halle: http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/savifadok/volltexte/2009/1087/pdf/Tschacher.pdf and http://www.suedasien.uni-halle.de/SAWA/Tschacher.pdf).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mohan, Vasundhara (1987). Identity Crisis of Sri Lankan Muslims. Delhi: Mittal Publications. pp. 9–14,27–30,67–74,113–118.

- 1 2 3 McGilvray, DB (November 1998). "Arabs, Moors and Muslims: Sri Lankan Muslim ethnicity in regional perspective" (PDF). Contributions to Indian Sociology: 433–483. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- 1 2 Zemzem, Akbar (1970). The Life and Times of Marhoom Wappichi Marikar (booklet). Colombo.

- 1 2 "Analysis: Tamil-Muslim divide". BBC News World Edition. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ↑ "Race in Sri Lanka What Genetic evidence tells us". Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- 1 2 Papiha, S.S.; Mastana, S.S.; Jaysekara, R. (October 1996). "Genetic Variation in Sri Lanka". 68 (5): 707–737 [709]. JSTOR 41465515.

- 1 2 de Munck, Victor (2005). "Islamic Orthodoxy and Sufism in Sri Lanka". Anthropos: 401–414 [403]. JSTOR 40466546.

- 1 2 3 Mahroof, M. M. M. "Spoken Tamil Dialects Of The Muslims Of Sri Lanka: Language As Identity-Classifier". Islamic Studies. 34 (4): 407–426 [408]. JSTOR 20836916.

- ↑ Ross Brann, "The Moors?", Andalusia, New York University. Quote: "Andalusi Arabic sources, as opposed to later Mudéjar and Morisco sources in Aljamiado and medieval Spanish texts, neither refer to individuals as Moors nor recognize any such group, community or culture."

- ↑ Pieris, P.E. "Ceylon and the Hollanders 1658-1796". American Ceylon Mission Press, Tellippalai Ceylon 1918

- ↑ "Population by ethnic group, census years" (PDF). Department of Census & Statistics, Sri Lanka. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ↑ McGilvray, D.B (1998). "Arabs, Moors and Muslims: Sri Lankan Muslim ethnicity in regional perspective". Contributions to Indian Sociology. 32 (2): 433–483. doi:10.1177/006996679803200213.

- ↑ 216 th year commemoration today: Remembering His Holiness Bukhary Thangal Sunday Observer – January 5, 2003. Online version accessed on 2009-08-14

- ↑ R. Cheran, Darshan Ambalavanar, Chelva Kanaganayakam (1997) History and Imagination: Tamil Culture in the Global Context. 216 pages, ISBN 978-1-894770-36-1

Further reading

- Victor C. de Munck. Experiencing History Small: An analysis of political, economic and social change in a Sri Lankan village. History & Mathematics: Historical Dynamics and Development of Complex Societies. Edited by Peter Turchin, Leonid Grinin, Andrey Korotayev, and Victor C. de Munck, pp. 154–169. Moscow: KomKniga, 2006. ISBN 5-484-01002-0