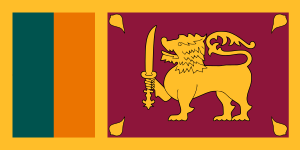

British Sri Lankans

| (බ්රිතාන්ය ශ්රී ලාංකිකයන්) பிரித்தானிய இலங்கையர் | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

|

Sri Lankan residents ~200,000 (2011)[1] Sri Lankan-born residents 67,938 (2001 Census) 106,000 (2009 ONS estimate) Other population estimates 110,000 (2002 Berghof Research Center estimate) 150,000 (2007 Tamil Information Centre estimate) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Sinhala, English, Tamil | |

| Religion | |

| Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Roman Catholicism, Protestantism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Sri Lankan |

British Sri Lankans (Sinhalese: බ්රිතාන්ය ශ්රී ලාංකිකයන්, Tamil: பிரித்தானிய இலங்கையர்) are a demographic construct that contains people who can trace their ancestry to Sri Lanka. It can refer to a variety of ethnicities and races, including Sinhalese, Tamils, Moors/Muslims, and Burghers.

History

Pre-Republic "Lanka"

Since the times of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, Sri Lanka historically had contact with Western Europe by being a stop on the highly profitable trade routes between the West and the East, whether through Arabic traders, or directly through Western European traders. The term "serendipity" comes from the Latin word used by Romans for the island.[2]

The first Western Europeans to make substantial contact with Sri Lanka were the Portuguese, followed by the Dutch and then finally the British. Sri Lankans have since been migrating to Britain for several centuries, up from the time of British ruled Ceylon.[3]

Republic of Sri Lanka

Between the 1950s to the 1980s, the United Kingdom served as the major immigration destination for highly-educated Sri Lankans, due to the liberal immigration rules given to Sri Lanka thanks to the politics surrounding post-empire connections such as the Commonwealth of Nations.

This initial group of immigrants consisted of a very settled group of people who followed a migration model of a single journey with a settled home at the end of it. Many of these people who came are well-educated and very well off economically and have become established in British society.

During the 1960s, understaffing in the UK’s National Health Service opened up the opportunity for many Sri Lankans to become doctors and consultants; others managed to secure other white-collar jobs.

Before 1983, when the Civil War started, social spaces for a Sri Lankan elite existed, there were hardly any ethnic boundaries and all ethnicities attended Sri Lankan High Commission receptions and the frequent intra-school sports competitions organized by Sri Lankan schools alumnae. During that time the public perceived the Sri Lankan community as one of the most successful immigrant communities in the UK. Especially during the 1970s, political organization increased among both Tamils and Sinhalese.[4]

Civil War in Sri Lanka

The onset of the Sri Lankan Civil War in the 1980s and 1990s caused a large scale exodus of Tamils to countries in the West. The Sri Lankan Tamils who emigrated to the UK often came on student visas (or family reunion visas for the family of said people) due to the well-educated in Sri Lanka being literate in English. This resulted in the first generation diaspora falling into highly professional jobs such as medicine and law after studying at British educational facilities.[5][6]

The British Born Generation

The children of first generation immigrants are a third grouping that have predominantly come-of-age in the late 2000s and 2010s. These children often grew up without siblings due to the low birth rates in the community, with one child for two parents being the norm.[7], but often fared better economic and cultural prospects than other similar refugee groups due to the strong education ethic imposed by Hindu culture.[8]

This grouping has been widely praised as docile and hard-working, with little problems relating to criminality and anti-social behaviour, and high levels of educational achievement. A number of reports and articles has praised the community as "middle class" and "progressive".[9]

Culture

As Sri Lankans are similar to Indians (Hindus, Buddhists and Christians)[10], it has often meant that Sri Lankans unknowingly assimilate into the local Indian cultures, particularly due to the small size of the Sri Lankan community, thanks to intermixing at shops and temples.[11]

Religion

Sri Lankans in the United Kingdom predominantly come from Tamil heritage, which has led to a situation where Christianity is more statistically prevalent among the community than Buddhism, but the unique manner in how Christians kept traditional Hindu Sri Lankan Tamil culture and simply imposed the laws of the Christian Bible has meant that religious divisions between Hindus and Christians are not stark.[12]

Hinduism nevertheless continues to be a cultural rallying point for most Sri Lankan Tamils. A number of temples have been built throughout the UK in order to service the needs of Sri Lankan Tamils, including the Sivan Kovil and Murugan Kovil in West London, though these temples do not necessarily serve as community building organisations due to Hinduism's lack of requirement for temple visits. The community mainly follow the Saivite sect.[13]

The smaller Sinhalese community has also been well served by a large network of Buddhist temples, including a major Sinhalese one at Kingsbury in London called Vihara, and six other prominent Sinhalese temples that have been ethnically linked to the community.[14] "Though present London Buddhist Vihāra traces its birth to 1926, until the arrival of three Sri Lankan monks as residents in 1928, the premises in Ealing seems to have functioned as Headquarters of British Maha Bodhi Society."

British Born Generation

A unique aspect of the emigration of Sri Lankan Tamils during the civil war was that they scattered around Europe, into smaller towns and villages, and hence assimilated and integrated into the local culture in different ways. It often means that a second generation Sri Lankan Tamil may not know other Sri Lankan Tamils, and therefore cultural similarities among the second generation community can be hard to find.[15]

Demographics

The 2001 Census recorded 67,938 Sri Lankan-born UK residents,[16] and the Office for National Statistics estimates the equivalent figure for 2009 to be 106,000.[17] The Tamil Information Centre estimates that, as of 2007, 170,000 Sri Lankans were resident in the UK.[18]

The largest community of Sri Lanka born immigrants live in London, with an estimated population of 50,000 in 2001 or 0.7% of the London population, with smaller populations in the West and East Midlands.[19]

Tamils

The UK has always had a strong, albeit small, population of Sri Lankan Tamils deriving from colonial era immigration between Sri Lanka and the UK, but a surge in emigration from Sri Lanka took place after 1983, as the civil war caused living conditions deteriorate and placed many inhabitants in danger. It is now estimated that the current population of British Sri Lankan Tamils numbers around 100,000 to 200,000.[20]

The largest population of British Sri Lankan Tamils can be found in London, chiefly in Harrow (West London) and Tooting (South London).[21] The community generally has far lower birth rates in comparison to other South Asian ethnic groups, with one child for two parents being the norm.[22]

Unlike immigrants to countries in Continental Europe, the majority of Sri Lankan Tamils that went to live in Anglosaxon countries achieved entry through non-refugee methods such as educational visas and family reunion visas, owing to the highly educated in Sri Lanka being literate in English as well as Tamil. This resulted in the first generation diaspora falling into highly professional jobs such as medicine and law after studying at British educational facilities.[23][24]

The result was that the community was perceived as being similar to the rest of the Hindu Indian community (see:Ugandan Indian Refugees) and therefore also gave them a more middle class image.[25] The community did not suffer from the problems with criminality, anti-social behaviour, or poor socioeconomic demographics that have plagued other communities such as Muslims.[26]

Sinhalese

The number of Sinhalese people in the UK is not known as the UK government doesn’t record statistics on language and the Sinhalese have to classify themselves as either Asian British or Asian Other. Out of the Asians, the Sri Lankans were the most likely to hold a formal qualification and to work in white-collar occupations. Sri Lankans mainly worked in health professions, engineering, business and property services, and the retail and manufacturing sectors, in large numbers.

The main and oldest organisation representing the Sinhalese community in the UK are the UK Sinhala association.[27] The newspaper Lanka Viththi was created in 1997 to provide a Sinhala newspaper for the Sinhalese community.[28] In 2006, a Sinhala TV channel called Kesara TV was set up in London to provide the Sinhala speaking people of the UK a TV channel in Sinhala.[29]

In March 2009, www.sleventsinuk.com was officially launched by His Excellency the High Commissioner Justice Nihal Jayasinghe at the Sri Lanka High Commission in the UK. The website is exclusively meant for the Sri Lankan community and it offers space to publicise all current and past events organised by the Sri Lankans living in the UK. The website enjoys the acceptability and positive feedback from its viewing audience as it became the most famous Sri Lankan Events website within a short period since its launch in the UK.

Community

Organisations

- UK Sinhala association

- Festival Of Cricket (FOC) – Organized by Sri Lankan OBA's in the UK

Newspapers

Website

- www.sleventsinuk.com[30]

- www.apisrilankan.com[31] ( Sri Lankan Community Website UK )

- www.sripola.co.uk[32]

Notable Sri Lankan Brits

References

- ↑ "Working with Sri Lanka". UK in Sri Lanka. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ↑ "Pre-Colonial Sri Lanka".

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- ↑ http://www.berghof-center.org/uploads/download/boc26e.pdf

- ↑ "SNIS" (PDF).

- ↑ "FT".

- ↑ "SMC" (PDF).

- ↑ "Children of Refugees" (PDF).

- ↑ "Financial Times".

- ↑ "India Telegraph".

- ↑ "Encyclopedia of Sri Lankan Diaspora".

- ↑ "Christianity in Sri Lanka".

- ↑ "Hinduism Today".

- ↑ "Promoting Buddhism in the UK".

- ↑ "Another specific feature of Tamils is that they are scattered throughout the country." (PDF).

- ↑ "Country-of-birth database". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Archived from the original on 2009-06-17. Retrieved 2009-11-08.

- ↑ "Estimated population resident in the United Kingdom, by foreign country of birth (Table 1.3)". Office for National Statistics. September 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ "Sri Lanka: Mapping exercise" (PDF). London: International Organization for Migration. February 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ↑ "Born abroad: Sri Lanka". BBC News. 2005-09-07. Retrieved 2009-11-08.

- ↑ "IOM" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-26.

- ↑ "The Economist".

- ↑ "SMC" (PDF).

- ↑ "SNIS" (PDF).

- ↑ "FT".

- ↑ "Unique Socioeconomic Positioning" (PDF).

- ↑ "Children of Refugees" (PDF).

- ↑ Dr. Tilak S. Fernando . (2007). Meeting with Labour Party in London . Available: Dr. Tilak S. Fernando . Last accessed 28 March 2010.

- ↑ Dr. Tilak S. Fernando . (2007). TENTH ANNIVERSARY OF SINHALA NEWSPAPER IN THE U.K. . Available: http://www.infolanka.com/org/diary/219.html. Last accessed 28 March 2010.

- ↑ Lanka Newspapers. (2006). Sri Lankan launches Sinhala TV channel in UK . Available: http://www.lankanewspapers.com/news/2006/7/7632.html. Last accessed 28 March 2010.

- ↑ www.sleventsinuk.com

- ↑ www.apisrilankan.com

- ↑ www.sripola.co.uk Archived January 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.