Spider-Man

| Spider-Man | |

|---|---|

|

Cover of Web of Spider-Man #129.1 (Oct. 2012) Art by Mike McKone and Morry Hollowell | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Marvel Comics |

| First appearance |

Amazing Fantasy #15 (August 1962) |

| Created by |

Stan Lee Steve Ditko |

| In-story information | |

| Alter ego | Peter Benjamin Parker |

| Species | Human mutate |

| Team affiliations |

Avengers Daily Bugle Future Foundation New Avengers Jean Grey School for Higher Learning Parker Industries |

| Notable aliases | Ricochet,[1] Dusk,[2] Prodigy,[3] Hornet,[4] Ben Reilly,[5] Scarlet Spider,[6] Iron Spider[7] |

| Abilities |

|

Spider-Man is a fictional superhero appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. The character was created by writer-editor Stan Lee and writer-artist Steve Ditko, and first appeared in the anthology comic book Amazing Fantasy #15 (August 1962) in the Silver Age of Comic Books. Lee and Ditko conceived the character as an orphan being raised by his Aunt May and Uncle Ben in New York City after his parents Richard and Mary Parker were killed in a plane crash, and as a teenager, having to deal with the normal struggles of adolescence in addition to those of a costumed crime-fighter. Spider-Man's creators gave him super strength and agility, the ability to cling to most surfaces, shoot spider-webs using wrist-mounted devices of his own invention, which he calls "web-shooters", and react to danger quickly with his "spider-sense", enabling him to combat his foes.

When Spider-Man first appeared in the early 1960s, teenagers in superhero comic books were usually relegated to the role of sidekick to the protagonist. The Spider-Man series broke ground by featuring Peter Parker, the high school student from Queens behind Spider-Man's secret identity and with whose "self-obsessions with rejection, inadequacy, and loneliness" young readers could relate.[8] While Spider-Man had all the makings of a sidekick, unlike previous teen heroes such as Bucky and Robin, Spider-Man had no superhero mentor like Captain America and Batman; he thus had to learn for himself that "with great power there must also come great responsibility"—a line included in a text box in the final panel of the first Spider-Man story but later retroactively attributed to his guardian, the late Uncle Ben.

Marvel has featured Spider-Man in several comic book series, the first and longest-lasting of which is titled The Amazing Spider-Man. Over the years, the Peter Parker character has developed from shy, nerdy New York City high school student to troubled but outgoing college student, to married high school teacher to, in the late 2000s, a single freelance photographer. In the 2010s, he joins the Avengers, Marvel's flagship superhero team. Spider-Man's nemesis Doctor Octopus also took on the identity for a story arc spanning 2012–2014, following a body swap plot in which Peter appears to die.[9] Separately, Marvel has also published books featuring alternate versions of Spider-Man, including Spider-Man 2099, which features the adventures of Miguel O'Hara, the Spider-Man of the future; Ultimate Spider-Man, which features the adventures of a teenaged Peter Parker in an alternate universe; and Ultimate Comics Spider-Man, which depicts the teenager Miles Morales, who takes up the mantle of Spider-Man after Ultimate Peter Parker's supposed death. Miles is later brought into mainstream continuity, where he works alongside Peter.

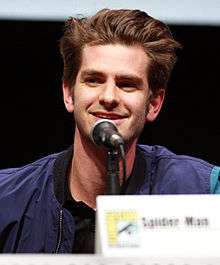

Spider-Man is one of the most popular and commercially successful superheroes.[10] As Marvel's flagship character and company mascot, he has appeared in countless forms of media, including several animated and live action television series, syndicated newspaper comic strips, and in a series of films. The character was first portrayed in live action by Danny Seagren in Spidey Super Stories, a The Electric Company skit which ran from 1974 to 1977.[11] In films, Spider-Man has been portrayed by actors Tobey Maguire (2002–2007), Andrew Garfield (2012–2014),[12] and Tom Holland, who has portrayed the character in the Marvel Cinematic Universe since 2016. Reeve Carney starred as Spider-Man in the 2010 Broadway musical Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark.[13] Spider-Man has been well received as a superhero and comic book character, and he is often ranked as one of the most popular comic book characters of all time, alongside DC Comics' most famous superheroes, Batman, Superman and Wonder Woman.

Publication history

Creation and development

In 1962, with the success of the Fantastic Four, Marvel Comics editor and head writer Stan Lee was casting about for a new superhero idea. He said the idea for Spider-Man arose from a surge in teenage demand for comic books, and the desire to create a character with whom teens could identify.[15]:1 In his autobiography, Lee cites the non-superhuman pulp magazine crime fighter the Spider (see also The Spider's Web and The Spider Returns) as a great influence,[14]:130 and in a multitude of print and video interviews, Lee stated he was further inspired by seeing a spider climb up a wall—adding in his autobiography that he has told that story so often he has become unsure of whether or not this is true.[note 1] Although at the time teenage superheroes were usually given names ending with "boy", Lee says he chose "Spider-Man" because he wanted the character to age as the series progressed, and moreover felt the name "Spider-Boy" would have made the character sound inferior to other superheroes.[16] At that time Lee had to get only the consent of Marvel publisher Martin Goodman for the character's approval. In a 1986 interview, Lee described in detail his arguments to overcome Goodman's objections.[note 2] Goodman eventually agreed to a Spider-Man tryout in what Lee in numerous interviews recalled as what would be the final issue of the science-fiction and supernatural anthology series Amazing Adult Fantasy, which was renamed Amazing Fantasy for that single issue, #15 (cover-dated August 1962, on sale June 5, 1962).[17] In particular, Lee stated that the fact that it had already been decided that Amazing Fantasy would be cancelled after issue #15 was the only reason Goodman allowed him to use Spider-Man.[16] While this was indeed the final issue, its editorial page anticipated the comic continuing and that "The Spiderman [sic] ... will appear every month in Amazing."[17][18]

Regardless, Lee received Goodman's approval for the name Spider-Man and the "ordinary teen" concept, and approached artist Jack Kirby. As comics historian Greg Theakston recounts, Kirby told Lee about an unpublished character on which he had collaborated with Joe Simon in the 1950s, in which an orphaned boy living with an old couple finds a magic ring that granted him superhuman powers. Lee and Kirby "immediately sat down for a story conference", Theakston writes, and Lee afterward directed Kirby to flesh out the character and draw some pages.[19] Steve Ditko would be the inker.[note 3] When Kirby showed Lee the first six pages, Lee recalled, "I hated the way he was doing it! Not that he did it badly—it just wasn't the character I wanted; it was too heroic".[19]:12 Lee turned to Ditko, who developed a visual style Lee found satisfactory. Ditko recalled:

One of the first things I did was to work up a costume. A vital, visual part of the character. I had to know how he looked ... before I did any breakdowns. For example: A clinging power so he wouldn't have hard shoes or boots, a hidden wrist-shooter versus a web gun and holster, etc. ... I wasn't sure Stan would like the idea of covering the character's face but I did it because it hid an obviously boyish face. It would also add mystery to the character....[20]

Although the interior artwork was by Ditko alone, Lee rejected Ditko's cover art and commissioned Kirby to pencil a cover that Ditko inked.[17] As Lee explained in 2010, "I think I had Jack sketch out a cover for it because I always had a lot of confidence in Jack's covers."[21]

In an early recollection of the character's creation, Ditko described his and Lee's contributions in a mail interview with Gary Martin published in Comic Fan #2 (Summer 1965): "Stan Lee thought the name up. I did costume, web gimmick on wrist & spider signal."[22] At the time, Ditko shared a Manhattan studio with noted fetish artist Eric Stanton, an art-school classmate who, in a 1988 interview with Theakston, recalled that although his contribution to Spider-Man was "almost nil", he and Ditko had "worked on storyboards together and I added a few ideas. But the whole thing was created by Steve on his own... I think I added the business about the webs coming out of his hands."[19]:14

Kirby disputed Lee's version of the story, and claimed Lee had minimal involvement in the character's creation. According to Kirby, the idea for Spider-Man had originated with Kirby and Joe Simon, who in the 1950s had developed a character called the Silver Spider for the Crestwood Publications comic Black Magic, who was subsequently not used.[note 4] Simon, in his 1990 autobiography, disputed Kirby's account, asserting that Black Magic was not a factor, and that he (Simon) devised the name "Spider-Man" (later changed to "The Silver Spider"), while Kirby outlined the character's story and powers. Simon later elaborated that his and Kirby's character conception became the basis for Simon's Archie Comics superhero the Fly.[23] Artist Steve Ditko stated that Lee liked the name Hawkman from DC Comics, and that "Spider-Man" was an outgrowth of that interest.[20]

Simon concurred that Kirby had shown the original Spider-Man version to Lee, who liked the idea and assigned Kirby to draw sample pages of the new character but disliked the results—in Simon's description, "Captain America with cobwebs".[note 5] Writer Mark Evanier notes that Lee's reasoning that Kirby's character was too heroic seems unlikely—Kirby still drew the covers for Amazing Fantasy #15 and the first issue of The Amazing Spider-Man. Evanier also disputes Kirby's given reason that he was "too busy" to draw Spider-Man in addition to his other duties since Kirby was, said Evanier, "always busy".[24]:127 Neither Lee's nor Kirby's explanation explains why key story elements like the magic ring were dropped; Evanier states that the most plausible explanation for the sudden change was that Goodman, or one of his assistants, decided that Spider-Man as drawn and envisioned by Kirby was too similar to the Fly.[24]:127

Author and Ditko scholar Blake Bell writes that it was Ditko who noted the similarities to the Fly. Ditko recalled that, "Stan called Jack about the Fly", adding that "[d]ays later, Stan told me I would be penciling the story panel breakdowns from Stan's synopsis". It was at this point that the nature of the strip changed. "Out went the magic ring, adult Spider-Man and whatever legend ideas that Spider-Man story would have contained". Lee gave Ditko the premise of a teenager bitten by a spider and developing powers, a premise Ditko would expand upon to the point he became what Bell describes as "the first work for hire artist of his generation to create and control the narrative arc of his series". On the issue of the initial creation, Ditko states, "I still don't know whose idea was Spider-Man".[25] Kirby noted in a 1971 interview that it was Ditko who "got Spider-Man to roll, and the thing caught on because of what he did".[26] Lee, while claiming credit for the initial idea, has acknowledged Ditko's role, stating, "If Steve wants to be called co-creator, I think he deserves [it]".[27] He has further commented that Ditko's costume design was key to the character's success; since the costume completely covers Spider-Man's body, people of all races could visualize themselves inside the costume and thus more easily identify with the character.[16] Writer Al Nickerson believes "that Stan Lee and Steve Ditko created the Spider-Man that we are familiar with today [but that] ultimately, Spider-Man came into existence, and prospered, through the efforts of not just one or two, but many, comic book creators".[28]

Commercial success

A few months after Spider-Man's introduction, publisher Goodman reviewed the sales figures for that issue and was shocked to find it was one of the nascent Marvel's highest-selling comics.[29]:97 A solo ongoing series followed, beginning with The Amazing Spider-Man #1 (cover-dated March 1963). The title eventually became Marvel's top-selling series[8]:211 with the character swiftly becoming a cultural icon; a 1965 Esquire poll of college campuses found that college students ranked Spider-Man and fellow Marvel hero the Hulk alongside Bob Dylan and Che Guevara as their favorite revolutionary icons. One interviewee selected Spider-Man because he was "beset by woes, money problems, and the question of existence. In short, he is one of us."[8]:223 Following Ditko's departure after issue #38 (July 1966), John Romita, Sr. replaced him as penciler and would draw the series for the next several years. In 1968, Romita would also draw the character's extra-length stories in the comics magazine The Spectacular Spider-Man, a proto-graphic novel designed to appeal to older readers. It only lasted for two issues, but it represented the first Spider-Man spin-off publication, aside from the original series' summer annuals that began in 1964.[30]

An early 1970s Spider-Man story led to the revision of the Comics Code. Previously, the Code forbade the depiction of the use of illegal drugs, even negatively. However, in 1970, the Nixon administration's Department of Health, Education, and Welfare asked Stan Lee to publish an anti-drug message in one of Marvel's top-selling titles.[8]:239 Lee chose the top-selling The Amazing Spider-Man; issues #96–98 (May–July 1971) feature a story arc depicting the negative effects of drug use. In the story, Peter Parker's friend Harry Osborn becomes addicted to pills. When Spider-Man fights the Green Goblin (Norman Osborn, Harry's father), Spider-Man defeats the Green Goblin, by revealing Harry's drug addiction. While the story had a clear anti-drug message, the Comics Code Authority refused to issue its seal of approval. Marvel nevertheless published the three issues without the Comics Code Authority's approval or seal. The issues sold so well that the industry's self-censorship was undercut and the Code was subsequently revised.[8]:239

In 1972, a second monthly ongoing series starring Spider-Man began: Marvel Team-Up, in which Spider-Man was paired with other superheroes and villains.[31] From that point on there have generally been at least two ongoing Spider-Man series at any time. In 1976, his second solo series, Peter Parker, the Spectacular Spider-Man began running parallel to the main series.[32] A third series featuring Spider-Man, Web of Spider-Man, launched in 1985 to replace Marvel Team-Up.[33] The launch of a fourth monthly title in 1990, the "adjectiveless" Spider-Man (with the storyline "Torment"), written and drawn by popular artist Todd McFarlane, debuted with several different covers, all with the same interior content. The various versions combined sold over 3 million copies, an industry record at the time. Several limited series, one-shots, and loosely related comics have also been published, and Spider-Man makes frequent cameos and guest appearances in other comic series.[32][34] In 1996 The Sensational Spider-Man was created to replace Web of Spider-Man.[35]

In 1998 writer-artist John Byrne revamped the origin of Spider-Man in the 13-issue limited series Spider-Man: Chapter One (December 1998 – October 1999), similar to Byrne's adding details and some revisions to Superman's origin in DC Comics' The Man of Steel.[36] At the same time the original The Amazing Spider-Man was ended with issue #441 (November 1998), and The Amazing Spider-Man was restarted with vol. 2, #1 (January 1999).[37] In 2003 Marvel reintroduced the original numbering for The Amazing Spider-Man and what would have been vol. 2, #59 became issue #500 (December 2003).[37]

When primary series The Amazing Spider-Man reached issue #545 (December 2007), Marvel dropped its spin-off ongoing series and instead began publishing The Amazing Spider-Man three times monthly, beginning with #546–548 (all January 2008).[38] The three times monthly scheduling of The Amazing Spider-Man lasted until November 2010 when the comic book was increased from 22 pages to 30 pages each issue and published only twice a month, beginning with #648–649 (both November 2010).[39][40] The following year, Marvel launched Avenging Spider-Man as the first spinoff ongoing series in addition to the still twice monthly The Amazing Spider-Man since the previous ones were cancelled at the end of 2007.[38] The Amazing series temporarily ended with issue #700 in December 2012, and was replaced by The Superior Spider-Man, which had Doctor Octopus serve as the new Spider-Man, having taken over Peter Parker's body. Superior was an enormous commercial success for Marvel,[41] and ran for 31-issue before the real Peter Parker returned in a newly relaunched The Amazing Spider-Man #1 in April 2014.[42]

Fictional character biography

In Forest Hills, Queens, New York,[43] Midtown High School student Peter Parker is a science-whiz orphan living with his Uncle Ben and Aunt May. As depicted in Amazing Fantasy #15 (August 1962), he is bitten by a radioactive spider (erroneously classified as an insect in the panel) at a science exhibit and "acquires the agility and proportionate strength of an arachnid".[44] Along with super strength, Parker gains the ability to adhere to walls and ceilings. Through his native knack for science, he develops a gadget that lets him fire adhesive webbing of his own design through small, wrist-mounted barrels. Initially seeking to capitalize on his new abilities, Parker dons a costume and, as "Spider-Man", becomes a novelty television star. However, "He blithely ignores the chance to stop a fleeing thief, [and] his indifference ironically catches up with him when the same criminal later robs and kills his Uncle Ben." Spider-Man tracks and subdues the killer and learns, in the story's next-to-last caption, "With great power there must also come—great responsibility!"[45]

Despite his superpowers, Parker struggles to help his widowed aunt pay rent, is taunted by his peers—particularly football star Flash Thompson—and, as Spider-Man, engenders the editorial wrath of newspaper publisher J. Jonah Jameson.[46][47] As he battles his enemies for the first time,[48] Parker finds juggling his personal life and costumed adventures difficult. In time, Peter graduates from high school,[49] and enrolls at Empire State University (a fictional institution evoking the real-life Columbia University and New York University),[50] where he meets roommate and best friend Harry Osborn, and girlfriend Gwen Stacy,[51] and Aunt May introduces him to Mary Jane Watson.[48][52][53] As Peter deals with Harry's drug problems, and Harry's father is revealed to be Spider-Man's nemesis the Green Goblin, Peter even attempts to give up his costumed identity for a while.[54][55] Gwen Stacy's father, New York City Police detective captain George Stacy is accidentally killed during a battle between Spider-Man and Doctor Octopus (#90, November 1970).[56]

In issue #121 (June 1973),[48] the Green Goblin throws Gwen Stacy from a tower of either the Brooklyn Bridge (as depicted in the art) or the George Washington Bridge (as given in the text).[57][58] She dies during Spider-Man's rescue attempt; a note on the letters page of issue #125 states: "It saddens us to say that the whiplash effect she underwent when Spidey's webbing stopped her so suddenly was, in fact, what killed her."[59] The following issue, the Goblin appears to kill himself accidentally in the ensuing battle with Spider-Man.[60]

Working through his grief, Parker eventually develops tentative feelings toward Watson, and the two "become confidants rather than lovers".[61] A romantic relationship eventually develops, with Parker proposing to her in issue #182 (July 1978), and being turned down an issue later.[62] Parker went on to graduate from college in issue #185,[48] and becomes involved with the shy Debra Whitman and the extroverted, flirtatious costumed thief Felicia Hardy, the Black Cat,[63] whom he meets in issue #194 (July 1979).[48]

From 1984 to 1988, Spider-Man wore a black costume with a white spider design on his chest. The new costume originated in the Secret Wars limited series, on an alien planet where Spider-Man participates in a battle between Earth's major superheroes and villains.[64] He continues wearing the costume when he returns, starting in The Amazing Spider-Man #252. The change to a longstanding character's design met with controversy, "with many hardcore comics fans decrying it as tantamount to sacrilege. Spider-Man's traditional red and blue costume was iconic, they argued, on par with those of his D.C. rivals Superman and Batman."[65] The creators then revealed the costume was an alien symbiote which Spider-Man is able to reject after a difficult struggle,[66] though the symbiote returns several times as Venom for revenge.[48]

Parker proposes to Watson a second time in The Amazing Spider-Man #290 (July 1987), and she accepts two issues later, with the wedding taking place in The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #21 (1987). It was promoted with a real-life mock wedding using models, including Tara Shannon as Watson,[67] with Stan Lee officiating at the June 5, 1987, event at Shea Stadium.[68][69] However, David Michelinie, who scripted based on a plot by editor-in-chief Jim Shooter, said in 2007, "I didn't think they actually should [have gotten] married. ... I had actually planned another version, one that wasn't used."[68]

In a controversial storyline, Peter becomes convinced that Ben Reilly, the Scarlet Spider (a clone of Peter created by his college professor Miles Warren) is the real Peter Parker, and that he, Peter, is the clone. Peter gives up the Spider-Man identity to Reilly for a time, until Reilly is killed by the returning Green Goblin and revealed to be the clone after all.[70] In stories published in 2005 and 2006 (such as "The Other"), he develops additional spider-like abilities including biological web-shooters, toxic stingers that extend from his forearms, the ability to stick individuals to his back, enhanced Spider-sense and night vision, and increased strength and speed. Peter later becomes a member of the New Avengers, and reveals his civilian identity to the world,[71] increasing his already numerous problems. His marriage to Mary Jane and public unmasking are later erased in another controversial[72] storyline "One More Day", in a Faustian bargain with the demon Mephisto that results in several other adjustments to the timeline, including the resurrection of Harry Osborn and the return of Spider-Man's traditional tools and powers.[73]

That storyline came at the behest of editor-in-chief Joe Quesada, who said, "Peter being single is an intrinsic part of the very foundation of the world of Spider-Man".[72] It caused unusual public friction between Quesada and writer J. Michael Straczynski, who "told Joe that I was going to take my name off the last two issues of the [story] arc" but was talked out of doing so.[74] At issue with Straczynski's climax to the arc, Quesada said, was

...that we didn't receive the story and methodology to the resolution that we were all expecting. What made that very problematic is that we had four writers and artists well underway on [the sequel arc] "Brand New Day" that were expecting and needed "One More Day" to end in the way that we had all agreed it would. ... The fact that we had to ask for the story to move back to its original intent understandably made Joe upset and caused some major delays and page increases in the series. Also, the science that Joe was going to apply to the retcon of the marriage would have made over 30 years of Spider-Man books worthless, because they never would have had happened. ...[I]t would have reset way too many things outside of the Spider-Man titles. We just couldn't go there....[74]

Following the "reboot", Parker's identity was no longer known to the general public; however, he revealed it to other superheroes.[75] and others have deduced it. Parker's Aunt May marries J. Jonah Jameson's father, Jay Jameson.[76] Parker became an employee of the think-tank Horizon Labs.[77] In issue #700, the dying supervillain Doctor Octopus swaps bodies with Parker, who remains as a presence in Doctor Octopus's mind,[78] prompting a two-year storyline in the series The Superior Spider-Man in which Peter Parker is absent and Doctor Octopus is Spider-Man. Peter eventually regains control of his body.[79] Following Peter Parker's return, The Amazing Spider-Man was relaunched in April 2014, with Peter Parker becoming a billionaire after the formation of Parker Industries.[80][81] In December 2014, following the Death of Wolverine comic book, Spider-Man became the new headmaster of the Jean Grey School and began appearing more prominently in X-Men stories, taking Wolverine's role in the comic Wolverine and the X-Men.[82]

Personality

Comics historian Peter Sanderson[83]

As one contemporaneous journalist observed, "Spider-Man has a terrible identity problem, a marked inferiority complex, and a fear of women. He is anti-social, [sic] castration-ridden, racked with Oedipal guilt, and accident-prone ... [a] functioning neurotic".[43] Agonizing over his choices, always attempting to do right, he is nonetheless viewed with suspicion by the authorities, who seem unsure as to whether he is a helpful vigilante or a clever criminal.[84]

Notes cultural historian Bradford W. Wright,

Spider-Man's plight was to be misunderstood and persecuted by the very public that he swore to protect. In the first issue of The Amazing Spider-Man, J. Jonah Jameson, publisher of the Daily Bugle, launches an editorial campaign against the "Spider-Man menace." The resulting negative publicity exacerbates popular suspicions about the mysterious Spider-Man and makes it impossible for him to earn any more money by performing. Eventually, the bad press leads the authorities to brand him an outlaw. Ironically, Peter finally lands a job as a photographer for Jameson's Daily Bugle.[8]:212

The mid-1960s stories reflected the political tensions of the time, as early 1960s Marvel stories had often dealt with the Cold War and Communism.[8]:220–223 As Wright observes,

From his high-school beginnings to his entry into college life, Spider-Man remained the superhero most relevant to the world of young people. Fittingly, then, his comic book also contained some of the earliest references to the politics of young people. In 1968, in the wake of actual militant student demonstrations at Columbia University, Peter Parker finds himself in the midst of similar unrest at his Empire State University.... Peter has to reconcile his natural sympathy for the students with his assumed obligation to combat lawlessness as Spider-Man. As a law-upholding liberal, he finds himself caught between militant leftism and angry conservatives.[8]:234–235

Powers, skills, and equipment

A bite from a radioactive spider triggers mutations in Peter Parker's body, granting him superpowers.[85] In the original Lee-Ditko stories, Spider-Man has the ability to cling to walls, superhuman strength, a sixth sense ("spider-sense") that alerts him to danger, perfect balance and equilibrium, as well as superhuman speed and agility.[85] The character was originally conceived by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko as intellectually gifted, but later writers have depicted his intellect at genius level.[86] Academically brilliant, Parker has expertise in the fields of applied science, chemistry, physics, biology, engineering, mathematics, and mechanics. With his talents, he sews his own costume to conceal his identity, and he constructs many devices that complement his powers, most notably mechanical web-shooters.[85] This mechanism ejects an advanced adhesive, releasing web-fluid in a variety of configurations, including a single rope-like strand to swing from, a net to snare or bind enemies, and a simple glob to foul machinery or blind an opponent. He can also weave the web material into simple forms like a shield, a spherical protection or hemispherical barrier, a club, or a hang-glider wing. Other equipment include a light beacon that can either be used as a flashlight or project a "Spider-Signal" design, a specially modified camera that can take pictures automatically, and spider-tracers, which are spider-shaped adhesive homing beacons keyed to his own spider-sense.

Other versions

Due to Spider-Man's popularity in the mainstream Marvel Universe, publishers have been able to introduce different variations of Spider-Man outside of mainstream comics as well as reimagined stories in many other multiversed spinoffs such as Ultimate Spider-Man, Spider-Man 2099, and Spider-Man: India. Marvel has also made its own parodies of Spider-Man in comics such as Not Brand Echh, which was published in the late 1960s and featured such characters as Peter Pooper alias Spidey-Man,[87] and Peter Porker, the Spectacular Spider-Ham, who appeared in the 1980s. The fictional character has inspired a number of deratives such as a manga version of Spider-Man drawn by Japanese artist Ryoichi Ikegami as well as Hideshi Hino's The Bug Boy, which has been cited as inspired by Spider-Man.[88] Also the French comic Télé-Junior, which published strips based on popular TV series, produced original Spider-Man adventures in the late 1970s; artists included Gérald Forton, who later moved to America and worked for Marvel.[89]

Supporting characters

.jpg)

Spider-Man has had a large range of supporting characters introduced in the comics that are essential in the issues and storylines that star him. After his parents died, Peter Parker was raised by his loving aunt, May Parker, and his uncle and father figure, Ben Parker. After Uncle Ben is murdered by a burglar, Aunt May is virtually Peter's only family, and she and Peter are very close.[44]

J. Jonah Jameson is depicted as the publisher of the Daily Bugle and is Peter Parker's boss and as a harsh critic of Spider-Man, always saying negative things about the superhero in the newspaper. Despite his role as Jameson's publishing editor and confidant Robbie Robertson is always depicted as a supporter of both Peter Parker and Spider-Man.[46]

Eugene "Flash" Thompson is commonly depicted as Parker's high school tormentor and bully, but in later comic issues he becomes a friend to Peter.[46] Meanwhile, Harry Osborn, son of Norman Osborn, is most commonly recognized as Peter's best friend but has also been depicted sometimes as his rival in the comics.[48]

Peter Parker's romantic interests range between his first crush, the fellow high-school student Liz Allan,[46] to having his first date with Betty Brant,[90] the secretary to the Daily Bugle newspaper publisher J. Jonah Jameson. After his breakup with Betty Brant, Parker eventually falls in love with his college girlfriend Gwen Stacy,[48][51] daughter of New York City Police Department detective captain George Stacy, both of whom are later killed by supervillain enemies of Spider-Man.[56] Mary Jane Watson eventually became Peter's best friend and then his wife.[68] Felicia Hardy, the Black Cat, is a reformed cat burglar who had been Spider-Man's sole superhuman girlfriend and partner at one point.[63]

Enemies

Writers and artists over the years have established a rogues gallery of supervillains to face Spider-Man. In comics and in other media. As with the hero, the majority of the villains' powers originate with scientific accidents or the misuse of scientific technology, and many have animal-themed costumes or powers.[note 6] Examples are listed down below in the ordering of their original chronological appearance: Indicates a group team.

| Supervillain name / Supervillain team name | Notable alter ego / group member | First appearance | Creator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chameleon | Dmitri Anatoly Nikolayevich | The Amazing Spider-Man #1 (March 1963)[91][92] | Stan Lee[91][92] Steve Ditko[91][92] |

| Vulture | Adrian Toomes | The Amazing Spider-Man #2 (May 1963)[93][94] | Stan Lee[93][95] Steve Ditko[93] |

| Doctor Octopus1 | Doctor Otto Gunther Octavius | The Amazing Spider-Man #3 (July 1963)[92] | Stan Lee[96][97] Steve Ditko[15][97] |

| Sandman | William Baker / Flint Marko | The Amazing Spider-Man #4 (September 1963)[98][99] | Stan Lee[98][99] Steve Ditko[98][99] |

| Lizard | Dr. Curt Connors | The Amazing Spider-Man #6 (November 1963)[100][101][102] | Stan Lee[100][101][102] Steve Ditko[100][101][102] |

| Electro | Maxwell Dillon | The Amazing Spider-Man #9 (February 1964)[103][104] | Stan Lee[105] Steve Ditko[105] |

| Mysterio | Quentin Beck | The Amazing Spider-Man #13 (June 1964)[106] | Stan Lee[106][107] Steve Ditko[106][107] |

| Green Goblin[108]2 | Norman Osborn2 Harry Osborn[109] |

The Amazing Spider-Man #14 (July 1964)[108] | Stan Lee[108][110] Steve Ditko[108][110] |

| Kraven the Hunter | Sergei Kravinoff | The Amazing Spider-Man #15 (August 1964)[111][112] | Stan Lee[111] Steve Ditko[111] |

| Sinister Six[113] | List of members | The Amazing Spider-Man annual #1 (1964) | Stan Lee[114] Steve Ditko[114] |

| Scorpion | Mac Gargan | The Amazing Spider-Man #20 (January 1965) | Stan Lee[115] Steve Ditko[115] |

| Rhino | Aleksei Mikhailovich Sytsevich | The Amazing Spider-Man #41 (October 1966)[116] | Stan Lee[117] John Romita, Sr.[117] |

| Shocker | Herman Schultz | The Amazing Spider-Man #46 (March 1967)[118] | Stan Lee[119] John Romita, Sr.[119] |

| Kingpin | Wilson Fisk | The Amazing Spider-Man #50 (July 1967)[120] [121] |

Stan Lee[122] John Romita, Sr.[122] |

| Morbius[123] | Michael Morbius | The Amazing Spider-Man #101 (January 1971)[124] | Roy Thomas[124] Gil Kane[125] |

| Jackal[126] | Miles Warren | The Amazing Spider-Man #129 (February 1974)[126] | Gerry Conway[126]10 Ross Andru[126] |

| Black Cat | Felicia Hardy | The Amazing Spider-Man #194 (July 1979)[127] | Marv Wolfman Keith Pollard[127] |

| Hydro-Man[128] | Morris Bench | The Amazing Spider-Man #212 (January 10, 1981)[129][130] | Denny O'Neil John Romita, Jr. |

| Hobgoblin | Roderick Kingsley | The Amazing Spider-Man #238 (March 1983) | Roger Stern[131][132] John Romita Sr.[131][133] |

| Venom3 | Eddie Brock3 | The Amazing Spider-Man #300 (May 1988)15[134][135] | David Michelinie[136] |

| Carnage | Cletus Kasady | The Amazing Spider-Man #361 (April 1992)[138] | David Michelinie[139][140] Erik Larsen[141] Mark Bagley[139] |

Archenemies

Unlike a lot of well known rivalries in comics book depictions. Spider-Man is cited to have more than one archenemy and it can be debated or disputed as to which one is worse:[142]

- ^ Doctor Octopus is regarded as one of Spider-Man's worst enemies and archenemy. He has been cited as the man Peter might have become if he had not been raised with a sense of responsibility.[15][143] He is infamous for defeating him the first time in battle and for almost marrying Peter's Aunt May. He is the core leader of the Sinister Six and has also referred himself as the "Master Planner". ("If This Be My Destiny...!")[144] Later depictions revealed him in Peter Parker's body where he was the titular character for a while.[143]

- ^ Norman Osborn using the Green Goblin alias is as commonly described as Spider-Man's archenemy.[142][145][146] Mostly after he is the first villain to uncover the hero's true identity, being responsible for setting up the death of Spider-Man's girlfriend in one of the most famous Spider-Man stories of all time which helped end the Silver Age of Comic Books and begin the Bronze Age of Comic Books.[142] He was thought to be dead after that but writers help bring him back from the 1990s and he returned to plague Spider-Man once more in the comic books (such as being involved of the killing of Aunt May) and other heroes (such as the Avengers[147]). He is also an enemy of Spider-Man sometimes just as himself and not just only as his Goblin persona.[148]

- ^ Another character commonly described as an archenemy is Venom. Eddie Brock as Venom is commonly described as the mirror version or the evil version of Spider-Man in many ways.[92][134][142] Venom's goals is usually depicted as trying to ruin Spider-Man's life and mess with Spider-Man's head when it comes to targeting enemies.[137] Venom is cited as being one of the most popular Spider-Man villains.[149] This popularity has led him to be an established iconic character of his own with own comic book stories.[134][150]

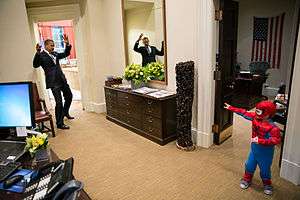

Cultural influence

In The Creation of Spider-Man, comic book writer-editor and historian Paul Kupperberg calls the character's superpowers "nothing too original"; what was original was that outside his secret identity, he was a "nerdy high school student".[151]:5 Going against typical superhero fare, Spider-Man included "heavy doses of soap-opera and elements of melodrama". Kupperberg feels that Lee and Ditko had created something new in the world of comics: "the flawed superhero with everyday problems". This idea spawned a "comics revolution".[151]:6 The insecurity and anxieties in Marvel's early 1960s comic books such as The Amazing Spider-Man, The Incredible Hulk, and X-Men ushered in a new type of superhero, very different from the certain and all-powerful superheroes before them, and changed the public's perception of them.[152] Spider-Man has become one of the most recognizable fictional characters in the world, and has been used to sell toys, games, cereal, candy, soap, and many other products.[153]

Spider-Man has become Marvel's flagship character, and has often been used as the company mascot. When Marvel became the first comic book company to be listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 1991, the Wall Street Journal announced "Spider-Man is coming to Wall Street"; the event was in turn promoted with an actor in a Spider-Man costume accompanying Stan Lee to the Stock Exchange.[8]:254 Since 1962, hundreds of millions of comics featuring the character have been sold around the world.[154] Spider-Man is the world's most profitable superhero.[155] In 2014, global retail sales of licensed products related to Spider-Man reached approximately $1.3 billion.[156] Comparatively, this amount exceeds the global licensing revenue of Batman, Superman, and the Avengers combined.[155]

Spider-Man joined the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade from 1987 to 1998 as one of the balloon floats,[157] designed by John Romita Sr.,[158] one of the character's signature artists. A new, different Spider-Man balloon float is scheduled to appear from at least 2009 to 2011.[157]

When Marvel wanted to issue a story dealing with the immediate aftermath of the September 11 attacks, the company chose the December 2001 issue of The Amazing Spider-Man.[159] In 2006, Spider-Man garnered major media coverage with the revelation of the character's secret identity,[160] an event detailed in a full page story in the New York Post before the issue containing the story was even released.[161]

In 2008, Marvel announced plans to release a series of educational comics the following year in partnership with the United Nations, depicting Spider-Man alongside UN Peacekeeping Forces to highlight UN peacekeeping missions.[162] A BusinessWeek article listed Spider-Man as one of the top ten most intelligent fictional characters in American comics.[163]

Rapper Eminem has cited Spider-Man as one of his favorite comic book superheroes.[164][165]

In 2015, the Supreme Court of the United States decided Kimble v. Marvel Entertainment, LLC, a case concerning royalties on a patent for an imitation web-shooter. The opinion for the Court, by Justice Elena Kagan, included several Spider-Man references, concluding with the statement that "with great power there must also come—great responsibility".[166]

Reception

IGN staff on placing Spider-Man as the number one hero of Marvel.[167]

Spider-Man was declared the number one superhero on Bravo's Ultimate Super Heroes, Vixens, and Villains TV series in 2005.[168] Empire magazine placed him as the fifth-greatest comic book character of all time.[169] Wizard magazine placed Spider-Man as the third greatest comic book character on their website.[170] In 2011, Spider-Man placed third on IGN's Top 100 Comic Book Heroes of All Time, behind DC Comics characters Superman and Batman.[167] and sixth in their 2012 list of "The Top 50 Avengers".[171] In 2014, IGN identified Spider-Man the greatest Marvel Comics character of all time.[172] A 2015 poll at Comic Book Resources named Spider-Man the greatest Marvel character of all time.[173] IGN described him as the common everyman that represents many normal people but also noting his uniqueness compared to many top-tiered superheroes with his many depicted flaws as a superhero. IGN noted that despite being one of the most tragic superheroes of all time that he is "one of the most fun and snarky superheroes in existence."[167] Empire noted and praised that despite the many tragedies that Spider-Man faces that he retains his sense of humour at all times with his witty wisecracks. The magazine website aspraised the depiction of his "iconic" superhero poses describing it as "a top artist's dream".[170]

George Marston of Newsarama placed Spider-Man's origin story as the greatest origin story of all time opining that "Spider-Man's origin combines all of the most classic aspects of pathos, tragedy and scientific wonder into the perfect blend for a superhero origin."[174]

Real-life comparisons

Real-life people who have been compared to Spider-Man for their climbing feats include:

- In 1981, skyscraper-safety activist Dan Goodwin, wearing a Spider-Man suit, scaled the Sears Tower in Chicago, Illinois, the Renaissance Tower in Dallas, Texas, and the John Hancock Center in Chicago, Illinois.[175]

- Alain Robert, nicknamed "Spider-Man", is a rock and urban climber who has scaled more than 70 tall buildings using his hands and feet, without using additional devices. He sometimes wears a Spider-Man suit during his climbs. In May 2003, he was paid approximately $18,000 to climb the 312-foot (95 m) Lloyd's building to promote the premiere of the movie Spider-Man on the British television channel Sky Movies.

- "The Human Spider", alias Bill Strother, scaled the Lamar Building in Augusta, Georgia in 1921.[176]

Awards

From the character's inception, Spider-Man stories have won numerous awards, including:

- 1962 Alley Award: Best Short Story—"Origin of Spider-Man" by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, Amazing Fantasy #15

- 1963 Alley Award: Best Comic: Adventure Hero title—The Amazing Spider-Man

- 1963 Alley Award: Top Hero—Spider-Man

- 1964 Alley Award: Best Adventure Hero Comic Book—The Amazing Spider-Man

- 1964 Alley Award: Best Giant Comic—The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #1

- 1964 Alley Award: Best Hero—Spider-Man

- 1965 Alley Award: Best Adventure Hero Comic Book—The Amazing Spider-Man

- 1965 Alley Award: Best Hero—Spider-Man

- 1966 Alley Award: Best Comic Magazine: Adventure Book with the Main Character in the Title—The Amazing Spider-Man

- 1966 Alley Award: Best Full-Length Story—"How Green was My Goblin", by Stan Lee & John Romita, Sr., The Amazing Spider-Man #39

- 1967 Alley Award: Best Comic Magazine: Adventure Book with the Main Character in the Title—The Amazing Spider-Man

- 1967 Alley Award Popularity Poll: Best Costumed or Powered Hero—Spider-Man

- 1967 Alley Award Popularity Poll: Best Male Normal Supporting Character—J. Jonah Jameson, The Amazing Spider-Man

- 1967 Alley Award Popularity Poll: Best Female Normal Supporting Character—Mary Jane Watson, The Amazing Spider-Man

- 1968 Alley Award Popularity Poll: Best Adventure Hero Strip—The Amazing Spider-Man

- 1968 Alley Award Popularity Poll: Best Supporting Character—J. Jonah Jameson, The Amazing Spider-Man

- 1969 Alley Award Popularity Poll: Best Adventure Hero Strip—The Amazing Spider-Man

- 1997 Eisner Award: Best Artist/Penciller/Inker or Penciller/Inker Team—1997 Al Williamson, Best Inker: Untold Tales of Spider-Man #17-18

- 2002 Eisner Award: Best Serialized Story—The Amazing Spider-Man vol. 2, #30–35: "Coming Home", by J. Michael Straczynski, John Romita, Jr., and Scott Hanna

In other media

Spider-Man has appeared in comics, cartoons, films, video games, coloring books, novels, records, and children's books.[153] On television, he first starred in the ABC animated series Spider-Man (1967–1970);[177] Spidey Super Stories (1974-1977) on PBS; and the CBS live action series The Amazing Spider-Man (1978–1979), starring Nicholas Hammond. Other animated series featuring the superhero include the syndicated Spider-Man (1981–1982), Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends (1981–1983), Fox Kids' Spider-Man (1994–1998), Spider-Man Unlimited (1999–2000), Spider-Man: The New Animated Series (2003), The Spectacular Spider-Man (2008–2009), and Ultimate Spider-Man (2012-2017).[178]

A tokusatsu series featuring Spider-Man was produced by Toei and aired in Japan. It is commonly referred to by its Japanese pronunciation "Supaidā-Man".[179] Spider-Man also appeared in other print forms besides the comics, including novels, children's books, and the daily newspaper comic strip The Amazing Spider-Man, which debuted in January 1977, with the earliest installments written by Stan Lee and drawn by John Romita, Sr.[180] Spider-Man has been adapted to other media including games, toys, collectibles, and miscellaneous memorabilia, and has appeared as the main character in numerous computer and video games on over 15 gaming platforms.

Spider-Man was featured in a trilogy of live-action films directed by Sam Raimi and starring Tobey Maguire as the titular superhero. The first Spider-Man film of the trilogy was released on May 3, 2002; followed by Spider-Man 2 (2004) and Spider-Man 3 (2007). A third sequel was originally scheduled to be released in 2011, however Sony later decided to reboot the franchise with a new director and cast. The reboot, titled The Amazing Spider-Man, was released on July 3, 2012; directed by Marc Webb and starring Andrew Garfield as the new Spider-Man.[181][182][183] It was followed by The Amazing Spider-Man 2 (2014).[184][185] In 2015, Sony and Disney made a deal for Spider-Man to appear in the Marvel Cinematic Universe.[186] Tom Holland made his debut as Spider-Man in the MCU film Captain America: Civil War (2016), before later starring in Spider-Man: Homecoming (2017); directed by Jon Watts.[187][188] Holland has been confirmed to reprise his role as Spider-Man for the upcoming Avengers: Infinity War (2018).[189]

A Broadway musical, Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, began previews on November 14, 2010 at the Foxwoods Theatre on Broadway, with the official opening night on June 14, 2011.[190][191] The music and lyrics were written by Bono and The Edge of the rock group U2, with a book by Julie Taymor, Glen Berger, Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa.[192] Turn Off the Dark is currently the most expensive musical in Broadway history, costing an estimated $70 million.[193] In addition, the show's unusually high running costs are reported to be about $1.2 million per week.[194]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Lee, Stan; Mair, George (2002). Excelsior!: The Amazing Life of Stan Lee. Fireside. ISBN 0-684-87305-2.

He goes further in his biography, claiming that even while pitching the concept to publisher Martin Goodman, "I can't remember if that was literally true or not, but I thought it would lend a big color to my pitch."

- ↑ Detroit Free Press interview with Stan Lee, quoted in The Steve Ditko Reader by Greg Theakston (Pure Imagination, Brooklyn, NY; ISBN 1-56685-011-8), p. 12 (unnumbered). "He gave me 1,000 reasons why Spider-Man would never work. Nobody likes spiders; it sounds too much like Superman; and how could a teenager be a superhero? Then I told him I wanted the character to be a very human guy, someone who makes mistakes, who worries, who gets acne, has trouble with his girlfriend, things like that. [Goodman replied,] 'He's a hero! He's not an average man!' I said, 'No, we make him an average man who happens to have super powers, that's what will make him good.' He told me I was crazy".

- ↑ Ditko, Steve (2000). Roy Thomas, ed. Alter Ego: The Comic Book Artist Collection. TwoMorrows Publishing. ISBN 1-893905-06-3. "'Stan said a new Marvel hero would be introduced in #15 [of what became titled Amazing Fantasy]. He would be called Spider-Man. Jack would do the penciling and I was to ink the character.' At this point still, Stan said Spider-Man would be a teenager with a magic ring which could transform him into an adult hero—Spider-Man. I said it sounded like the Fly, which Joe Simon had done for Archie Comics. Stan called Jack about it but I don't know what was discussed. I never talked to Jack about Spider-Man... Later, at some point, I was given the job of drawing Spider-Man'".

- ↑ Jack Kirby in "Shop Talk: Jack Kirby", Will Eisner's Spirit Magazine #39 (February 1982): "Spider-Man was discussed between Joe Simon and myself. It was the last thing Joe and I had discussed. We had a strip called 'The Silver Spider.' The Silver Spider was going into a magazine called Black Magic. Black Magic folded with Crestwood (Simon & Kirby's 1950s comics company) and we were left with the script. I believe I said this could become a thing called Spider-Man, see, a superhero character. I had a lot of faith in the superhero character that they could be brought back... and I said Spider-Man would be a fine character to start with. But Joe had already moved on. So the idea was already there when I talked to Stan".

- ↑ Simon, Joe, with Jim Simon. The Comic Book Makers (Crestwood/II, 1990) ISBN 1-887591-35-4. "There were a few holes in Jack's never-dependable memory. For instance, there was no Black Magic involved at all. ... Jack brought in the Spider-Man logo that I had loaned to him before we changed the name to The Silver Spider. Kirby laid out the story to Lee about the kid who finds a ring in a spiderweb, gets his powers from the ring, and goes forth to fight crime armed with The Silver Spider's old web-spinning pistol. Stan Lee said, 'Perfect, just what I want.' After obtaining permission from publisher Martin Goodman, Lee told Kirby to pencil-up an origin story. Kirby... using parts of an old rejected superhero named Night Fighter... revamped the old Silver Spider script, including revisions suggested by Lee. But when Kirby showed Lee the sample pages, it was Lee's turn to gripe. He had been expecting a skinny young kid who is transformed into a skinny young kid with spider powers. Kirby had him turn into... Captain America with cobwebs. He turned Spider-Man over to Steve Ditko, who... ignored Kirby's pages, tossed the character's magic ring, web-pistol and goggles... and completely redesigned Spider-Man's costume and equipment. In this life, he became high-school student Peter Parker, who gets his spider powers after being bitten by a radioactive spider. ... Lastly, the Spider-Man logo was redone and a dashing hyphen added".

- ↑ Mondello, Salvatore (March 2004). "Spider-Man: Superhero in the Liberal Tradition". The Journal of Popular Culture. X (1): 232–238. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1976.1001_232.x.

...a teenage superhero and middle-aged supervillains—an impressive rogues' gallery [that] includes such memorable knaves and grotesques as the Vulture...

References

- ↑ Amazing Spider-Man #434

- ↑ Spider-Man #91

- ↑ The Spectacular Spider-Man #257

- ↑ Sensational Spider-Man #27

- ↑ Amazing Spider-Man Annual #36

- ↑ The Amazing Spider-Man #149-151

- ↑ The Amazing Spider-Man #529

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Wright, Bradford W. (2001). Comic Book Nation. Johns Hopkins Press : Baltimore. ISBN 0-8018-7450-5.

- ↑ Sacks, Ethan (January 12, 2014). "Exclusive: Peter Parker to return from death in 'Amazing Spider-Man' #1 this April". New York Daily News.

- ↑ "Why Spider-Man is popular.". Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ↑ Weiss, Brett (October 2010). "Spidey Super Stories". Back Issue!. TwoMorrows Publishing (44): 23–28.

- ↑ "It's Official! Andrew Garfield to Play Spider-Man!". Comingsoon.net. July 2, 2010. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Complete Cast Announced for Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark". Broadway.com. August 16, 2010. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- 1 2 Lee, Stan; Mair, George (2002). Excelsior!: The Amazing Life of Stan Lee. Fireside. ISBN 0-684-87305-2.

- 1 2 3 DeFalco, Tom; Lee, Stan (2001). O'Neill, Cynthia, ed. Spider-Man: The Ultimate Guide. New York: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 0-7894-7946-X.

- 1 2 3 Thomas, Roy (August 2011). "Stan Lee's Amazing Marvel Interview!". Alter Ego. TwoMorrows Publishing (104): 3–45.

- 1 2 3 Amazing Fantasy (Marvel, 1962 series) at the Grand Comics Database: "1990 copyright renewal lists the publication date as June 5, 1962"; "[T]he decision to cancel the series had not been made when it went to print, since it is announced that future issues will include a Spider-Man feature."

- ↑ "Important Announcement from the Editor!", Amazing Fantasy #15 (August 1962), reprinted at Sedlmeier, Cory, ed. (2007). Amazing Fantasy Omnibus. Marvel Publishing. p. 394. ISBN 978-0785124580.

- 1 2 3 Theakston, Greg (2002). The Steve Ditko Reader. Brooklyn, NY: Pure Imagination. ISBN 1-56685-011-8.

- 1 2 Ditko, Steve (2000). Roy Thomas, ed. Alter Ego: The Comic Book Artist Collection. TwoMorrows Publishing. ISBN 1-893905-06-3.

- ↑ "Deposition of Stan Lee". Los Angeles, California: United States District Court, Southern District of New York: "Marvel Worldwide, Inc., et al., vs. Lisa R. Kirby, et al.". December 8, 2010. p. 37.

- ↑ Ditko interview (Summer 1965). "Steve Ditko – A Portrait of the Master". Comic Fan #2 (Larry Herndon) via Ditko.Comics.org (Blake Bell, ed.). Archived from the original on February 28, 2012. Retrieved April 3, 2008. Additional, February 28, 2012.

- ↑ Simon, Joe (2011). Joe Simon: My Life in Comics. London, UK: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-84576-930-7.

- 1 2 Evanier, Mark; Gaiman, Neil (2008). Kirby: King of Comics. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-9447-X.

- ↑ Bell, Blake. Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko (2008). Fantagraphic Books.p.54-57.

- ↑ Skelly, Tim. "Interview II: 'I created an army of characters, and now my connection to them is lost.'" (Initially broadcast over WNUR-FM on "The Great Electric Bird", May 14, 1971. Transcribed and published in The Nostalgia Journal #27.) Reprinted in The Comics Journal Library Volume One: Jack Kirby, George, Milo ed. May 2002, Fantagraphics Books. p. 16

- ↑ Ross, Jonathon. In Search of Steve Ditko, BBC 4, September 16, 2007.

- ↑ Nickerson, Al. "Who Really Created Spider-Man? Archived February 17, 2009, at WebCite" P.I.C. News, February 5, 2009. Accessed February 17, 2009. Archived 2009-02-17.

- ↑ Daniels, Les (1991). Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-3821-9.

- ↑ Saffel, Steve. Spider-Man the Icon: The Life and Times of a Pop Culture Phenomenon (Titan Books, 2007) ISBN 978-1-84576-324-4, "A Not-So-Spectacular Experiment", p. 31

- ↑ Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1970s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 60. ISBN 978-0756692360.

Spider-Man was a proven hit, so Marvel decided to expand the wall-crawler's horizons with a new Spider-Man title...Its first issue featured Spidey teaming up with the Human Torch against the Sandman in a Christmas tale written by Roy Thomas with art by Ross Andru.

- 1 2 David, Peter; Greenberger, Robert (2010). The Spider-Man Vault: A Museum-in-a-Book with Rare Collectibles Spun from Marvel's Web. Running Press. p. 113. ISBN 0762437723.

- ↑ Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1980s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 147. ISBN 978-0756692360.

Spider-Man swung into the pages of an all-new ongoing series in this first issue by writer Louise Simonson and penciler Greg LaRocque.

- ↑ Cowsill, Alan; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1990s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 184. ISBN 978-0756692360.

Todd McFarlane was at the top of his game as an artist, and with Marvel's release of this new Spidey series he also got the chance to take on the writing duties. The sales of this series were nothing short of phenomenal, with approx. 2.5 million copies eventually printing, including special bagged editions and a number of variant covers.

- ↑ Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1970s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0756692360.

- ↑ Michael Thomas (August 22, 2000). "John Byrne: The Hidden Story". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved May 27, 2011.

- 1 2 Michael Thomas (August 5, 2008). "The Marvel 500s: How Many Are There?". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on July 9, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- 1 2 Schedeen, Jesse (November 8, 2011). "The Avenging Spider-Man #1 Review". IGN. j2 Global. Archived from the original on March 23, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ↑ "IGN: SDCC 10: Spider-Man: The End of Brand New Day". IGN. j2 Global. July 25, 2010. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ↑ Bremmer, Robyn; Morse, Ben (September 27, 2010). "The Next Big Thing: Spider-Man: Big Time". Marvel.com. Marvel Comics / Marvel Entertainment (The Walt Disney Company). Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Peter Parker Resurrected in Slott's Amazing Spider-Man". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ↑ Hanks, Henry (April 29, 2014). "Back from the brain dead, Peter Parker returns to 'Spider-Man' comics". Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- 1 2 Kempton, Sally, "Spiderman's [sic] Dilemma: Super-Anti-Hero in Forest Hills", The Village Voice, April 1, 1965

- 1 2 Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (a). Amazing Fantasy 15 (August 1962), New York City, New York: Marvel Comics

- ↑ Daniels, Les. Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics (Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1991) ISBN 0-8109-3821-9, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 Saffel, Steve. Spider-Man the Icon: The Life and Times of a Pop Culture Phenomenon (Titan Books, 2007) ISBN 978-1-84576-324-4, p. 21.

- ↑ Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (a). "Spider-Man"; "Spider-Man vs. The Chameleon"; "Duel to the Death with the Vulture; "The Uncanny Threat of the Terrible Tinkerer!" The Amazing Spider-Man 1-2 (March, May 1963), New York, NY: Marvel Comics

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Amazing Spider-Man, The (Marvel, 1963 Series) at the Grand Comics Database

- ↑ Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (a). "The Menace of the Molten Man!" The Amazing Spider-Man 28 (September 1965), New York, NY: Marvel Comics

- ↑ Saffel, p. 51

- 1 2 Sanderson, Peter (2007). The Marvel Comics Guide to New York City. New York City: Pocket Books. pp. 30–33. ISBN 1-4165-3141-6.

- ↑ Lee, Stan (w), Romita, John (a). "The Birth of a Super-Hero!" The Amazing Spider-Man 42 (November 1966), New York, NY: Marvel Comics

- ↑ Saffel, p. 27

- ↑ Lee, Stan (w), Romita, John (p), Mickey Demeo (i). "Spider-Man No More!" The Amazing Spider-Man 50 (July 1967), New York, NY: Marvel Comics

- ↑ Lee, Stan (w), Kane, Gil (p), Giacoia, Frank (i). "The Spider or the Man?" The Amazing Spider-Man 100 (September 1971), New York, NY: Marvel Comics

- 1 2 Saffel, p. 60

- ↑ Saffel, p. 65, states, "In the battle that followed atop the Brooklyn Bridge (or was it the George Washington Bridge?)...." On page 66, Saffel reprints the panel of The Amazing Spider-Man #121, page 18, in which Spider-Man exclaims, "The George Washington Bridge! It figures Osborn would pick something named after his favorite president. He's got the same sort of hangup for dollar bills!" Saffel states, "The span portrayed...is the GW's more famous cousin, the Brooklyn Bridge. ... To address the contradiction in future reprints of the tale, though, Spider-Man's dialogue was altered so that he's referring to the Brooklyn Bridge. But the original snafu remains as one of the more visible errors in the history of comics."

- ↑ Sanderson, Marvel Universe, p. 84, notes, "[W]hile the script described the site of Gwen's demise as the George Washington Bridge, the art depicted the Brooklyn Bridge, and there is still no agreement as to where it actually took place."

- ↑ Saffel, p. 65

- ↑ Conway, Gerry (w), Kane, Gil (p), Romita, John (i). "The Night Gwen Stacy Died" The Amazing Spider-Man 121 (June 1973), New York, NY: Marvel Comics

- ↑ Sanderson, Marvel Universe, p. 85

- ↑ Blumberg, Arnold T. (Spring 2006). "'The Night Gwen Stacy Died': The End of Innocence and the 'Last Gasp of the Silver Age'". International Journal of Comic Art. 8 (1): 208.

- 1 2 Sanderson, Marvel Universe, p. 83

- ↑ Shooter, Jim (w), Zeck, Michael (p), Beatty, John, Abel, Jack, and Esposito, Mike (i). "Invasion" Marvel Super-Heroes Secret Wars 8 (December 1984), New York, NY: Marvel Comics

- ↑ Leupp, Thomas. "Behind the Mask: The Story of Spider-Man's Black Costume" Archived June 27, 2010, at WebCite, ReelzChannel.com, 2007, n.d. WebCitation archive.

- ↑ Simonson, Louise (w), LaRocque, Greg (p), Mooney, Jim and Colletta, Vince (i). "'Til Death Do Us Part!" Web of Spider-Man 1 (April 1985), New York, NY: Marvel Comics

- ↑ Gross, Michael (June 2, 1987). "Spider-Man to Wed Model". The New York Times. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Saffel, p. 124

- ↑ Shooter, Jim and Michelinie, David (w), Ryan, Paul (p), Colletta, Vince (i). "The Wedding" The Amazing Spider-Man Annual 21 (1987), New York City, New York: Marvel Comics

- ↑ "Life of Reilly". GreyHaven Magazine. NewComicsReviews.com. Archived from the original on February 5, 2004.

- ↑ Millar, Mark (w), McNiven, Steve (p), Vines, Dexter (i). "Civil War" Civil War 2 (August 2006), New York, NY: Marvel Comics

- 1 2 Weiland, Jonah. "The 'One More Day' Interviews with Joe Quesada, Pt. 1 of 5", Newsarama, December 28, 2007. WebCitation archive.

- ↑ Straczynski, J. Michael (w), Quesada, Joe (p), Miki, Danny (i). "One More Day Part 4" The Amazing Spider-Man 545 (December 2007), Marvel Comics

- 1 2 Weiland, Jonah. "The 'One More Day' Interviews with Joe Quesada, Pt. 2 of 5", Newsarama, December 31, 2007. WebCitation archive.

- ↑ New Avengers #51

- ↑ The Amazing Spider-Man #600

- ↑ The Amazing Spider-Man #648

- ↑ The Superior Spider-Man #1-29

- ↑ The Superior Spider-Man #30-31

- ↑ "Exclusive: Peter Parker to return from death in 'Amazing Spider-Man' #1 this April". Daily News. New York City. January 12, 2014. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ↑ "All-New Marvel NOW! Q&A: Amazing Spider-Man". Marvel. January 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Spider-Man and The X-Men (2014-Present)". Marvel Comics. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- ↑ Sanderson, Peter. Marvel Universe: The Complete Encyclopedia of Marvel's Greatest Characters (Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1998) ISBN 0-8109-8171-8, p. 75

- ↑ Daniels, p. 96

- 1 2 3 Gresh, Lois H., and Robert Weinberg. "The Science of Superheroes" (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2002) ISBN 0-471-02460-0 (preview)

- ↑ Kiefer, Kit; Couper-Smartt, Jonathan (2003). Marvel Encyclopedia Volume 4: Spider-Man. New York: Marvel Comics. ISBN 0-7851-1304-5.

- ↑ "examples of "Not Brand Echh" comics". Dialbforblog.com. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ↑ McCarthy, Helen, 500 Manga Heroes and Villains (Barron's Educational Series, 2006), ISBN 978-0-7641-3201-8,

- ↑ Lambiek comic shop and studio in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. "Lambiek Comiclopedia: Gérald Forton". Lambiek.net. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ↑ Lee, Stan, Origins of Marvel Comics (Simon and Schuster/Fireside Books, 1974) p. 137

- 1 2 3 DeFalco, Tom; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2008). "1960s". Marvel Chronicle A Year by Year History. Dorling Kindersley. p. 87. ISBN 978-0756641238.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Siegel, Lucas. "The 10 Greatest SPIDER-MAN Villains of ALL TIME!". Newsarama. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Beard, Jim. "ARCHRIVALS: SPIDER-MAN VS THE VULTURE". Marvel.com. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ Kyle, Scmidlin. "10 Spider-Man Villains (And Combinations) Deserving Of The Big Screen (7. The Vulture)". What Culture!. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

"He's been one of Spider-Man's most frequent and iconic antagonists ever since his first appearance in issue 2 of The Amazing Spider-Man.

- ↑ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 92: "Introduced in the lead story of The Amazing Spider-Man #2 and created by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, the Vulture was the first in a long line of animal-inspired super-villains that were destined to battle everyone's favorite web-slinger."

- ↑ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 93: "Dr. Octopus shared many traits with Peter Parker. They were both shy, both interested in science, and both had trouble relating to women...Otto Octavius even looked like a grown up Peter Parker. Lee and Ditko intended Otto to be the man Peter might have become if he hadn't been raised with a sense of responsibility.

- 1 2 Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "Spider-Man Versus Doctor Octopus" The Amazing Spider-Man 3 (July 1963)

- 1 2 3 Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1960s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 20. ISBN 978-0756692360.

In this installment, Stan Lee and Steve Ditko introduced Sandman – a super villain who could turn his entire body into sand with a single thought.

- 1 2 3 Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "Nothing Can Stop...The Sandman!" The Amazing Spider-Man 4 (September 1963)

- 1 2 3 DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 95

- 1 2 3 Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "Face-to-Face With...the Lizard!" The Amazing Spider-Man 6 (November 1963)

- 1 2 3 Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1960s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 20. ISBN 978-0756692360.

The Amazing Spider-Mans sixth issue introduced the Lizard.

- ↑ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 98

- ↑ Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "The Man Called Electro!" The Amazing Spider-Man 9 (February 1964)

- 1 2 Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1960s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 24. ISBN 978-0756692360.

Electro charged into Spider-Man's life for the first time in another [Stan] Lee and [Steve] Ditko effort that saw Peter Parker using his brilliant mind to outwit a foe.

- 1 2 3 Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "The Menace of... Mysterio!" The Amazing Spider-Man 13 (June 1964)

- 1 2 Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1960s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 25. ISBN 978-0756692360.

The Amazing Spider-Man #13 saw [Stan] Lee and [Steve] Ditko return to the creation of new super villains. This issue marked the debut of Mysterio, a former special effects expert named Quentin Beck.

- 1 2 3 4 Albert, Aaron. "Green Goblin Profile". About.com. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ↑ Beard, Jim. "SPIDER-MAN 3: THE SPIDER & THE GOBLIN". Marvel.com. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- 1 2 Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1960s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 26. ISBN 978-0756692360.

Spider-Man's arch nemesis, the Green Goblin, as introduced to readers as the 'most dangerous foe Spidey's ever fought.' Writer Stan Lee and artist Steve Ditko had no way of knowing how true that statement would prove to be in the coming years.

- 1 2 3 Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1960s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 26. ISBN 978-0756692360.

[Stan] Lee and [Steve] Ditko's newest villain, Kraven the Hunter, debuted in this issue.

- ↑ Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "Kraven the Hunter!" The Amazing Spider-Man 15 (August 1964)

- ↑ Valentine, Eve. "Who Are the Sinister Six? – An Introduction to Spider-Man’s Supervillain Group". Collider. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- 1 2 Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1960s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 27. ISBN 978-0756692360.

Spidey faced his first true team of super villains in an oversized 73-pages extravaganza written by [Stan] Lee with art by [Steve] Ditko.

- 1 2 Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1960s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 28. ISBN 978-0756692360.

Spider-Man felt the Scorpion's sting for the first time in another Stan Lee and Steve Ditko collaboration.

- ↑ Lee, Stan (w), Romita, Sr., John (p), Esposito, Mike (i). "The Horns of the Rhino!" The Amazing Spider-Man 41 (October 1966)

- 1 2 Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1960s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 36. ISBN 978-0756692360.

Now it was time for [John Romita, Sr.] to introduce a new Spidey villain with the help of [Stan] Lee. Out of their pooled creative energies was born the Rhino, a monstrous behemoth trapped in a durable rhinoceros suit.

- ↑ Lee, Stan (w), Romita, Sr., John (p), Romita, Sr., John (i). "The Sinister Shocker!" The Amazing Spider-Man 46 (March 1967)

- 1 2 Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1960s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 38. ISBN 978-0756692360.

[Stan] Lee and [John] Romita's second major Spidey villain appeared in the form of the Shocker, a criminal equipped with vibration-projecting gauntlets.

- ↑ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 122: "Stan Lee wanted to create a new kind of crime boss. Someone who treated crime as if it were a business...He pitched this idea to artist John Romita and it was Wilson Fisk who emerged in The Amazing Spider-Man #50."

- ↑ Lee, Stan (w), Romita, Sr., John (p), Esposito, Mike (i). "Spider-Man No More!" The Amazing Spider-Man 50 (July 1967)

- 1 2 Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1960s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 40. ISBN 978-0756692360.

Although he made his debut in the previous issue, it was in this [Stan] Lee and [John] Romita tale [The Amazing Spider-Man #51] that the Kingpin – real name Wilson Fisk – really left his mark on organized crime.

- ↑ Yehl, April, Schedeen, Jesse. "Top 25 Spider-Man villains: Part 2". IGN. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- 1 2 Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1970s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 59. ISBN 978-0756692360.

In the first issue of The Amazing Spider-Man to be written by someone other than Stan Lee...Thomas also managed to introduce a major new player to Spidey's life – the scientifically created vampire known as Morbius.

- ↑ Gross, Edward (2002). Spider-Man Confidential: From Comic Icon to Hollywood Hero. ISBN 0786887222.

- 1 2 3 4 Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1970s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 72. ISBN 978-0756692360.

Writer Gerry Conway and artist Ross Andru introduced two major new characters to Spider-Man's world and the Marvel Universe in this self-contained issue. Not only would the vigilante known as the Punisher go on to be one of the most important and iconic Marvel creations of the 1970s, but his instigator, the Jackal, would become the next big threat in Spider-Man's life.

- 1 2 Manning "1970s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 107: "Spider-Man wasn't exactly sure what to think about his luck when he met a beautiful new thief on the prowl named the Black Cat, courtesy of a story by writer Marv Wolfman and artist Keith Pollard."

- ↑

- ↑ Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1980s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 118. ISBN 978-0756692360.

In this issue, award-winning writer Denny O'Neil, with collaborator John Romita, Jr., introduced Hydro-Man.

- ↑ "AMAZING SPIDER-MAN (1963) #212". Marvel. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- 1 2 Manning "1980s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 133: "Writer Roger Stern and artists John Romita, Jr. and John Romita, Sr. introduced a new – and frighteningly sane – version of the [Green Goblin] concept with the debut of the Hobgoblin."

- ↑ David and Greenberger, pp. 68-69: "Writer Roger Stern is primarily remembered for two major contributions to the world of Peter Parker. One was a short piece entitled 'The Kid Who Collects Spider-Man'...[his] other major contribution was the introduction of the Hobgoblin."

- ↑ Greenberg, Glenn (August 2009). "When Hobby Met Spidey". Back Issue! (35). TwoMorrows Publishing. pp. 10–23.

- 1 2 3 "Venom is the 33rd greatest comic book character.". Empire.com. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ↑ Manning "1980s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 169: "In this landmark installment [issue #298], one of the most popular characters in the wall-crawler's history would begin to step into the spotlight courtesy of one of the most popular artists to ever draw the web-slinger."

- ↑ Comics Creators on Spider-Man, pg 148, Tom DeFalco. (Titan Books, 2004)

- 1 2 "Venom is number 22 on greatest comic book villain of all time". IGN. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Carnage is number 90 on greatest comic book villain of all time". IGN. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- 1 2 Cowsill, Alan; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1990s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 197. ISBN 978-0756692360.

Artist Mark Bagley's era of The Amazing Spider-Man hit its stride as Carnage revealed the true face of his evil. Carnage was a symbiotic offspring produced when Venom bonded to psychopath Cletus Kasady."

- ↑ Michelinie, David (w), Bagley, Mark (p), Emberlin,Randy (i). "Carnage: Part One" The Amazing Spider-Man 361 (April 1992)

- ↑ Papageorgiou, Solon. "10 facts about Batman, Spider-Man, Iron Man you didn't know.". Moviepilot. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Albert, Aaron. "Top ten comic book archenemies". About.com. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- 1 2 Hanks, Henry. "Events in landmark 'Spider-Man' issue have fans in a frenzy". CNN. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ Cronin, Brian. "50 Greatest Friends and Foes of Spider-Man: Villains #1-3". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ "The ULTIMATE SPIDER-MAN writer talks about Spidey's new Amazing Friends and lays the Osborns to rest once and for all | Marvel.com News". Marvel.com. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- ↑ "Love is in the air as Marvel.com's Secret Cabal picks the greatest Marvel romances of all in time for Valentine's Day | Marvel.com News". Marvel.com. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- ↑ Yehl, Joshua, Schedeen, Jess. "Top 25 Spider-Man Villain: Part 5". IGN. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ↑ "Norman Osborn is number 13 on greatest comic book villain of all time.". IGN. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Spider-Man villains tournament: Championship". IGN. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ↑ Shutt, Craig (August 1997). "Villain Turned Hero: Venom". Wizard (72). p. 37.

- 1 2 Kupperberg, Paul (2007). The Creation of Spider-Man. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 1-4042-0763-5.

- ↑ Fleming, James R. (2006). "Review of Superman on the Couch: What Superheroes Really Tell Us about Ourselves and Our Society. By Danny Fingeroth". ImageText. University of Florida. ISSN 1549-6732. Retrieved December 4, 2015.

- 1 2 Knowles, Christopher (2007). Our Gods Wear Spandex. illustrated by Joseph Michael Linsner. Weiser. p. 139.

- ↑ "Spider-Man Weaving a spell". Screen India. 2002. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- 1 2 Davis, Lauren (November 14, 2014). "This Superhero Is More Lucrative Than Batman And The Avengers Combined". io9. Gizmodo Media Group. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ↑ Block, Alex (November 13, 2014). "Which Superhero Earns $1.3 Billion a Year?". The Hollywood Reporter. Lynne Segall. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- 1 2 "Spider-Man Returning to Macy's Thanksgiving Day Paradede", Associated Press via WCBS (AM), August 17, 2009 Archived November 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Spurlock, J. David, and John Romita. John Romita Sketchbook. (Vanguard Productions: Lebanon, N.J. 2002) ISBN 1-887591-27-3, p. 45: Romita: "I designed the Spider-Man balloon float. When we went to Macy's to talk about it, Manny Bass was there. He's the genius who creates all these balloon floats. I gave him the sketches and he turned them into reality".

- ↑ Yarbrough, Beau (September 24, 2001). "Marvel to Take on World Trade Center Attack in "Amazing Spider-Man"". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved April 28, 2008.

- ↑ Staff (June 15, 2006). "Spider-Man Removes Mask at Last". BBC. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- ↑ Brady, Matt (June 14, 2006). "New York Post Spoils Civil War #2". Newsarama. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved April 2, 2008.

- ↑ Lane, Thomas (January 4, 2008). "Can Spider-Man help UN beat evil?". BBC. Retrieved April 29, 2008.

- ↑ Pisani, Joseph (June 1, 2006). "The Smartest Superheroes". Business Week Online. Retrieved November 25, 2007.

- ↑ Cohen, Johnathan (December 12, 2008). "Exclusive: Eminem Talks New Album, Book". Billboard.

- ↑ Lockett, Dee (April 2, 2015). "7 Fun Facts We Learned From Eminem’s Genius Annotations". Vulture.

- ↑ Caldwell, Patrick (June 22, 2015), "Justice Elena Kagan Had Some Fun Writing About Spider-Man", Mother Jones, retrieved June 23, 2015

- 1 2 3 "IGN's Top 100 Comic Book Heroes". Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ↑ "Ultimate Super Heroes, Vixens, and Villains Episode Guide 2005 – Ultimate Super Villains". TVGuide.com. Retrieved October 9, 2010.