Spanning tree

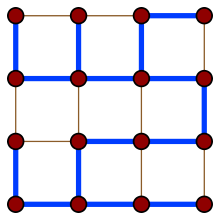

In the mathematical field of graph theory, a spanning tree T of an undirected graph G is a subgraph that is a tree which includes all of the vertices of G, with minimum possible number of edges. In general, a graph may have several spanning trees, but a graph that is not connected will not contain a spanning tree (but see Spanning forests below). If all of the edges of G are also edges of a spanning tree T of G, then G is a tree and is identical to T (that is, a tree has a unique spanning tree and it is itself).

Applications

Several pathfinding algorithms, including Dijkstra's algorithm and the A* search algorithm, internally build a spanning tree as an intermediate step in solving the problem.

In order to minimize the cost of power networks, wiring connections, piping, automatic speech recognition, etc., people often use algorithms that gradually build a spanning tree (or many such trees) as intermediate steps in the process of finding the minimum spanning tree.[1]

The Internet and many other telecommunications networks have transmission links that connect nodes together in a mesh topology that includes some loops. In order to "avoid bridge loops and "routing loops", many routing protocols designed for such networks—including the Spanning Tree Protocol, Open Shortest Path First, Link-state routing protocol, Augmented tree-based routing, etc. -- require each router to remember a spanning tree.

Definitions

A tree is a connected undirected graph with no cycles. It is a spanning tree of a graph G if it spans G (that is, it includes every vertex of G) and is a subgraph of G (every edge in the tree belongs to G). A spanning tree of a connected graph G can also be defined as a maximal set of edges of G that contains no cycle, or as a minimal set of edges that connect all vertices.

Fundamental cycles

Adding just one edge to a spanning tree will create a cycle; such a cycle is called a fundamental cycle. There is a distinct fundamental cycle for each edge; thus, there is a one-to-one correspondence between fundamental cycles and edges not in the spanning tree. For a connected graph with V vertices, any spanning tree will have V − 1 edges, and thus, a graph of E edges and one of its spanning trees will have E − V + 1 fundamental cycles. For any given spanning tree the set of all E − V + 1 fundamental cycles forms a cycle basis, a basis for the cycle space.[2]

Fundamental cutsets

Due to the notion of a fundamental cycle is the notion of a fundamental cutset. By deleting just one edge of the spanning tree, the vertices are partitioned into two disjoint sets. The fundamental cutset is defined as the set of edges that must be removed from the graph G to accomplish the same partition. Thus, each spanning tree defines a set of V − 1 fundamental cutsets, one for each edge of the spanning tree.[3]

The duality between fundamental cutsets and fundamental cycles is established by noting that cycle edges not in the spanning tree can only appear in the cutsets of the other edges in the cycle; and vice versa: edges in a cutset can only appear in those cycles containing the edge corresponding to the cutset. This duality can also be expressed using the theory of matroids, according to which a spanning tree is a base of the graphic matroid, a fundamental cycle is the unique circuit within the set formed by adding one element to the base, and fundamental cutsets are defined in the same way from the dual matroid.[4]

Spanning forests

In graphs that are not connected, there can be no spanning tree, and one must consider spanning forests instead. Here there are two competing definitions:

- Some authors consider a spanning forest to be a maximal acyclic subgraph of the given graph, or equivalently a graph consisting of a spanning tree in each connected component of the graph.[5]

- For other authors, a spanning forest is a forest that spans all of the vertices, meaning only that each vertex of the graph is a vertex in the forest. For this definition, even a connected graph may have a disconnected spanning forest, such as the forest in which each vertex forms a single-vertex tree.[6]

To avoid confusion between these two definitions, Gross & Yellen (2005) suggest the term "full spanning forest" for a spanning forest with the same connectivity as the given graph, while Bondy & Murty (2008) instead call this kind of forest a "maximal spanning forest".[7]

Counting spanning trees

The number t(G) of spanning trees of a connected graph is a well-studied invariant.

In specific graphs

In some cases, it is easy to calculate t(G) directly:

- If G is itself a tree, then t(G) = 1.

- When G is the cycle graph Cn with n vertices, then t(G) = n.

- For a complete graph with n vertices, Cayley's formula[8] gives the number of spanning trees as nn − 2.

- If G is the complete bipartite graph ,[9] then .

- For the n-dimensional hypercube graph ,[10] the number of spanning trees is .

In arbitrary graphs

More generally, for any graph G, the number t(G) can be calculated in polynomial time as the determinant of a matrix derived from the graph, using Kirchhoff's matrix-tree theorem.[11]

Specifically, to compute t(G), one constructs a square matrix in which the rows and columns are both indexed by the vertices of G. The entry in row i and column j is one of three values:

- The degree of vertex i, if i = j,

- −1, if vertices i and j are adjacent, or

- 0, if vertices i and j are different from each other but not adjacent.

The resulting matrix is singular, so its determinant is zero. However, deleting the row and column for an arbitrarily chosen vertex leads to a smaller matrix whose determinant is exactly t(G).

Deletion-contraction

If G is a graph or multigraph and e is an arbitrary edge of G, then the number t(G) of spanning trees of G satisfies the deletion-contraction recurrence t(G) = t(G − e) + t(G/e), where G − e is the multigraph obtained by deleting e and G/e is the contraction of G by e.[12] The term t(G − e) in this formula counts the spanning trees of G that do not use edge e, and the term t(G/e) counts the spanning trees of G that use e.

In this formula, if the given graph G is a multigraph, or if a contraction causes two vertices to be connected to each other by multiple edges, then the redundant edges should not be removed, as that would lead to the wrong total. For instance a bond graph connecting two vertices by k edges has k different spanning trees, each consisting of a single one of these edges.

Tutte polynomial

The Tutte polynomial of a graph can be defined as a sum, over the spanning trees of the graph, of terms computed from the "internal activity" and "external activity" of the tree. Its value at the arguments (1,1) is the number of spanning trees or, in a disconnected graph, the number of maximal spanning forests.[13]

The Tutte polynomial can also be computed using a deletion-contraction recurrence, but its computational complexity is high: for many values of its arguments, computing it exactly is #P-complete, and it is also hard to approximate with a guaranteed approximation ratio. The point (1,1), at which it can be evaluated using Kirchhoff's theorem, is one of the few exceptions.[14]

Algorithms

Construction

A single spanning tree of a graph can be found in linear time by either depth-first search or breadth-first search. Both of these algorithms explore the given graph, starting from an arbitrary vertex v, by looping through the neighbors of the vertices they discover and adding each unexplored neighbor to a data structure to be explored later. They differ in whether this data structure is a stack (in the case of depth-first search) or a queue (in the case of breadth-first search). In either case, one can form a spanning tree by connecting each vertex, other than the root vertex v, to the vertex from which it was discovered. This tree is known as a depth-first search tree or a breadth-first search tree according to the graph exploration algorithm used to construct it.[15] Depth-first search trees are a special case of a class of spanning trees called Trémaux trees, named after the 19th-century discoverer of depth-first search.[16]

Spanning trees are important in parallel and distributed computing, as a way of maintaining communications between a set of processors; see for instance the Spanning Tree Protocol used by OSI link layer devices or the Shout (protocol) for distributed computing. However, the depth-first and breadth-first methods for constructing spanning trees on sequential computers are not well suited for parallel and distributed computers.[17] Instead, researchers have devised several more specialized algorithms for finding spanning trees in these models of computation.[18]

Optimization

In certain fields of graph theory it is often useful to find a minimum spanning tree of a weighted graph. Other optimization problems on spanning trees have also been studied, including the maximum spanning tree, the minimum tree that spans at least k vertices, the spanning tree with the fewest edges per vertex, the spanning tree with the largest number of leaves, the spanning tree with the fewest leaves (closely related to the Hamiltonian path problem), the minimum diameter spanning tree, and the minimum dilation spanning tree.[19][20]

Optimal spanning tree problems have also been studied for finite sets of points in a geometric space such as the Euclidean plane. For such an input, a spanning tree is again a tree that has as its vertices the given points. The quality of the tree is measured in the same way as in a graph, using the Euclidean distance between pairs of points as the weight for each edge. Thus, for instance, a Euclidean minimum spanning tree is the same as a graph minimum spanning tree in a complete graph with Euclidean edge weights. However, it is not necessary to construct this graph in order to solve the optimization problem; the Euclidean minimum spanning tree problem, for instance, can be solved more efficiently in O(n log n) time by constructing the Delaunay triangulation and then applying a linear time planar graph minimum spanning tree algorithm to the resulting triangulation.[19]

Randomization

A spanning tree chosen randomly from among all the spanning trees with equal probability is called a uniform spanning tree. Wilson's algorithm can be used to generate uniform spanning trees in polynomial time by a process of taking a random walk on the given graph and erasing the cycles created by this walk.[21]

An alternative model for generating spanning trees randomly but not uniformly is the random minimal spanning tree. In this model, the edges of the graph are assigned random weights and then the minimum spanning tree of the weighted graph is constructed.[22]

Enumeration

Because a graph may have exponentially many spanning trees, it is not possible to list them all in polynomial time. However, algorithms are known for listing all spanning trees in polynomial time per tree.[23]

In infinite graphs

Every finite connected graph has a spanning tree. However, for infinite connected graphs, the existence of spanning trees is equivalent to the axiom of choice. An infinite graph is connected if each pair of its vertices forms the pair of endpoints of a finite path. As with finite graphs, a tree is a connected graph with no finite cycles, and a spanning tree can be defined either as a maximal acyclic set of edges or as a tree that contains every vertex.[24]

The trees within a graph may be partially ordered by their subgraph relation, and any infinite chain in this partial order has an upper bound (the union of the trees in the chain). Zorn's lemma, one of many equivalent statements to the axiom of choice, requires that a partial order in which all chains are upper bounded have a maximal element; in the partial order on the trees of the graph, this maximal element must be a spanning tree. Therefore, if Zorn's lemma is assumed, every infinite connected graph has a spanning tree.[24]

In the other direction, given a family of sets, it is possible to construct an infinite graph such that every spanning tree of the graph corresponds to a choice function of the family of sets. Therefore, if every infinite connected graph has a spanning tree, then the axiom of choice is true.[25]

In directed multigraphs

The idea of a spanning tree can be generalized to directed multigraphs.[26] Given a vertex v on a directed multigraph G, an oriented spanning tree T rooted at v is an acyclic subgraph of G in which every vertex other than v has outdegree 1. This definition is only satisfied when the “branches” of T point towards v.

See also

- Flooding algorithm

- Good spanning tree - spanning tree for embedded planar graph

References

- ↑ R. L. Graham and Pavol Hell. "On the History of the Minimum Spanning Tree Problem". 1985.

- ↑ Kocay & Kreher (2004), pp. 65–67.

- ↑ Kocay & Kreher (2004), pp. 67–69.

- ↑ Oxley, J. G. (2006), Matroid Theory, Oxford Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 3, Oxford University Press, p. 141, ISBN 978-0-19-920250-8.

- ↑ Bollobás, Béla (1998), Modern Graph Theory, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 184, Springer, p. 350, ISBN 978-0-387-98488-9; Mehlhorn, Kurt (1999), LEDA: A Platform for Combinatorial and Geometric Computing, Cambridge University Press, p. 260, ISBN 978-0-521-56329-1.

- ↑ Cameron, Peter J. (1994), Combinatorics: Topics, Techniques, Algorithms, Cambridge University Press, p. 163, ISBN 978-0-521-45761-3.

- ↑ Gross, Jonathan L.; Yellen, Jay (2005), Graph Theory and Its Applications (2nd ed.), CRC Press, p. 168, ISBN 978-1-58488-505-4; Bondy, J. A.; Murty, U. S. R. (2008), Graph Theory, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 244, Springer, p. 578, ISBN 978-1-84628-970-5.

- ↑ Aigner, Martin; Ziegler, Günter M. (1998), Proofs from THE BOOK, Springer-Verlag, pp. 141–146.

- ↑ Hartsfield, Nora; Ringel, Gerhard (2003), Pearls in Graph Theory: A Comprehensive Introduction, Courier Dover Publications, p. 100, ISBN 978-0-486-43232-8.

- ↑ Harary, Frank; Hayes, John P.; Wu, Horng-Jyh (1988), "A survey of the theory of hypercube graphs", Computers & Mathematics with Applications, 15 (4): 277–289, MR 949280, doi:10.1016/0898-1221(88)90213-1.

- ↑ Kocay, William; Kreher, Donald L. (2004), "5.8 The matrix-tree theorem", Graphs, Algorithms, and Optimization, Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications, CRC Press, pp. 111–116, ISBN 978-0-203-48905-5.

- ↑ Kocay & Kreher (2004), p. 109.

- ↑ Bollobás (1998), p. 351.

- ↑ Goldberg, L.A.; Jerrum, M. (2008), "Inapproximability of the Tutte polynomial", Information and Computation, 206 (7): 908–929, doi:10.1016/j.ic.2008.04.003; Jaeger, F.; Vertigan, D. L.; Welsh, D. J. A. (1990), "On the computational complexity of the Jones and Tutte polynomials", Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 108: 35–53, doi:10.1017/S0305004100068936.

- ↑ Kozen, Dexter (1992), The Design and Analysis of Algorithms, Monographs in Computer Science, Springer, p. 19, ISBN 978-0-387-97687-7.

- ↑ de Fraysseix, Hubert; Rosenstiehl, Pierre (1982), "A depth-first-search characterization of planarity", Graph theory (Cambridge, 1981), Ann. Discrete Math., 13, Amsterdam: North-Holland, pp. 75–80, MR 671906.

- ↑ Reif, John H. (1985), "Depth-first search is inherently sequential", Information Processing Letters, 20 (5): 229–234, MR 801987, doi:10.1016/0020-0190(85)90024-9.

- ↑ Gallager, R. G.; Humblet, P. A.; Spira, P. M. (1983), "A distributed algorithm for minimum-weight spanning trees", ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems, 5 (1): 66–77, doi:10.1145/357195.357200; Gazit, Hillel (1991), "An optimal randomized parallel algorithm for finding connected components in a graph", SIAM Journal on Computing, 20 (6): 1046–1067, MR 1135748, doi:10.1137/0220066; Bader, David A.; Cong, Guojing (2005), "A fast, parallel spanning tree algorithm for symmetric multiprocessors (SMPs)" (PDF), Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing, 65 (9): 994–1006, doi:10.1016/j.jpdc.2005.03.011.

- 1 2 Eppstein, David (1999), "Spanning trees and spanners" (PDF), in Sack, J.-R.; Urrutia, J., Handbook of Computational Geometry, Elsevier, pp. 425–461.

- ↑ Wu, Bang Ye; Chao, Kun-Mao (2004), Spanning Trees and Optimization Problems, CRC Press, ISBN 1-58488-436-3.

- ↑ Wilson, David Bruce (1996), "Generating random spanning trees more quickly than the cover time", Proceedings of the Twenty-eighth Annual ACM Symposium on the Theory of Computing (STOC 1996), pp. 296–303, MR 1427525, doi:10.1145/237814.237880.

- ↑ McDiarmid, Colin; Johnson, Theodore; Stone, Harold S. (1997), "On finding a minimum spanning tree in a network with random weights" (PDF), Random Structures & Algorithms, 10 (1-2): 187–204, MR 1611522, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2418(199701/03)10:1/2<187::AID-RSA10>3.3.CO;2-Y.

- ↑ Gabow, Harold N.; Myers, Eugene W. (1978), "Finding all spanning trees of directed and undirected graphs", SIAM Journal on Computing, 7 (3): 280–287, MR 0495152, doi:10.1137/0207024

- 1 2 Serre, Jean-Pierre (2003), Trees, Springer Monographs in Mathematics, Springer, p. 23.

- ↑ Soukup, Lajos (2008), "Infinite combinatorics: from finite to infinite", Horizons of combinatorics, Bolyai Soc. Math. Stud., 17, Berlin: Springer, pp. 189–213, MR 2432534, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-77200-2_10. See in particular Theorem 2.1, pp. 192–193.

- ↑ "Lionel Levine" (2011). "Sandpile groups and spanning trees of directed line graphs". Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series A. 118 (2): 350–364. ISSN 0097-3165. doi:10.1016/j.jcta.2010.04.001.