Spanish Army

| Ejército de Tierra Spanish Army | |

|---|---|

|

Seal of the Spanish Army | |

| Founded | 15th century – present |

| Country |

|

| Allegiance | Felipe VI |

| Type | Army |

| Role | Land force |

| Size | 77,343 personnel (2016)[1] |

| Part of | Spanish Ministry of Defense |

| Garrison/HQ | Buenavista Palace, Madrid |

| Mascot(s) | Crowned rampant eagle with Saint James cross |

| Commanders | |

| Chief of Staff of the Army |

Army General Francisco Javier Varela Salas[2] |

| Commander in Chief | King Felipe VI |

| Aircraft flown | |

| Attack helicopter | Tiger |

| Reconnaissance | MBB Bo 105 |

| Trainer |

Colibrí EC135 |

| Transport |

Chinook Cougar NH90 |

The Spanish Army (Spanish: Ejército de Tierra; lit. "Army of the Land/Ground") is the terrestrial army of the Spanish Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is one of the oldest active armies — dating back to the late 15th century.

History

The Spanish army has existed continuously since the reign of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella (late 15th century). The oldest and largest of the three services, its mission was the defense of Peninsular Spain, the Balearic Islands, the Canary Islands, Melilla, Ceuta and the Spanish islands and rocks off the northern coast of Africa.

Under the Habsburgs

During the 16th century, Habsburg Spain saw a steady growth in its military power. The Italian Wars (1494–1559) resulted in an ultimate Spanish victory and hegemony in northern Italy by expelling the French. During the war, the Spanish army transformed its organization and tactics, evolving from a primarily pike and halberd wielding force into the first pike and shot formation of arquebusiers and pikemen, known as the colunella. During the 16th century this formation evolved into the tercio infantry formation. The new formation and battle tactics were developed because of Spain's inability to field sufficient cavalry forces to face the heavy French cavalry.[3]

Backed by the financial resources drawn from the Americas,[4] Spain could afford to mount lengthy campaigns against her enemies, such as the long running Dutch revolt (1568–1609), defending Christian Europe from Ottoman raids and invasions, supporting the Catholic cause in the French civil wars and fighting England during the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604). The Spanish army grew in size from around 20,000 in the 1470s, to around 300,000 by the 1630s during the Thirty Years' War that tore Europe apart, requiring the recruitment of soldiers from across Europe.[5] With such numbers involved, Spain had trouble funding the war effort on so many fronts. The non-payment of troops led to many mutinies and events such as the Sack of Antwerp (1576), when unpaid tercio units looted the Dutch city.

The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) drew in Spain alongside most other European states. Spain entered the conflict with a strong position, but the ongoing fighting gradually eroded her advantages; first Dutch, then Swedish innovations had made the tercio more vulnerable, having less flexibility and firepower than its more modern equivalents.[6] Nevertheless, Spanish armies continued to win major battles and sieges throughout this period across large swathes of Europe. French entry into the war in 1635 put additional pressure on Spain, with the French victory at the Battle of Rocroi in 1643 being a major boost for the French. By the signing of the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, Spain was forced to accept the independence of the Dutch Republic.

In the second half of the century, a much reduced and increasingly neglected Spanish army became infamous for being poorly equipped and rarely paid.[7]

18th century

Spain remained an important naval and military power, depending on critical sea lanes stretching from Spain through the Caribbean and South America, and westwards towards Manila and the Far East.

The Army was reorganised on the French model and in 1704 the old Tercios were transformed into Regiments. The first modern military school (the Artillery School) was created in Segovia in 1764. Finally, in 1768 King Charles III sanctioned the "Royal Ordinances for the Regime, Discipline, Subordination and Service in His Armies", which were in force until 1978.[8]

Napoleonic era and Restoration

In the late 18th century, Bourbon-ruled Spain had an alliance with Bourbon-ruled France, and therefore did not have to fear a land war. Its only serious enemy was Britain, which had a powerful Royal Navy; Spain therefore concentrated its resources on its navy. When the French Revolution overthrew the Bourbons, a land war with France became a danger which the king tried to avoid. The Spanish army was ill-prepared. The officer corps was selected primarily on the basis of royal patronage, rather than merit. About a third of the junior officers have been promoted from the ranks, and they did have talent, but they had few opportunities for promotion or leadership. The rank-and-file were poorly trained peasants. Elite units included foreign regiments of Irishmen, Italians, Swiss, and Walloons, in addition to elite artillery and engineering units. Equipment was old-fashioned and in disrepair. The army lacked its own horses, oxen and mules for transportation, so these auxiliaries were operated by civilians, who might run away if conditions looked bad. In combat, small units fought well, but their old-fashioned tactics were hardly of use against the Napoleonic forces, despite repeated desperate efforts at last-minute reform.[9] When war broke out with France in 1808, the army was deeply unpopular. Leading generals were assassinated, and the army proved incompetent to handle command-and-control. Junior officers from peasant families deserted and went over to the insurgents; many units disintegrated. Spain was unable to mobilize its artillery or cavalry. In the war, there was one victory at the Battle of Bailén within the first 2 months of the start and with little time to prepare against the veteran French troops, which however not followed in its advantage - the French evacuated the peninsula all the way to the Ebro valley near the Pyrenees - and suffering many humiliating defeats of the Spanish regular Army after such auspicious start, proved to be the first sound defeat to the hitherto seemly unbeatable Imperial armies, and demonstrating that if given more or less equal forces than the usual mass superiority of the French as it happened forcing the surrender of a whole Division of the Imperial Army, this inspired many other nations formerly defeated by France, motivating first Austria and showed the force of nationwide resistance to Napoleon. Conditions however steadily worsened as Napoleon brought more effective troops into the peninsula, as the insurgents increasingly took control of Spain's battle against Napoleon in the oldest national trait of warfare, known by its vernacular name Guerrilla and more or less unified underground National Resistance for which traditional armies of the Time and warfare developed during the XVIII century were not organized or prepared yet. Napoleon ridiculed the Spanish standard army as "the worst in Europe". And the British who had to work with it agreed.[10] It was not the Army that defeated Napoleon, but the insurgent peasants whom Napoleon ridiculed as packs of "bandits led by monks"[11] or "rebels" in "insurgency" against the legitimate government of his brother, Joseph I implanted by him as a new monarch. By 1812, the army controlled only scattered enclaves, and could only harass the French with occasional raids. The morale of the army had reached a nadir, and reformers stripped the aristocratic officers of most of their legal privileges.[12]

Nineteen Century Colonial and Carlist Wars until second Restoration and American-Spanish war

further information: the Spanish Carlist Wars

During the XIX century Spain with a much reduced territory and Power recognized in Europe after the Congress of Vienna in 1814, had a renewed problem in the international arena, consequence of its former alliance with France that costed its main Fleets and many War damages in its military arsenals and Weapons factories, some of it caused by the British or Portuguese allies during the Peninsular campaign to prevent the French or Spain after the war to resume their services. Immediately after the War, while its administration was trying to come to terms with the local rebellions against a renewed Totalitarian monarchy, the overseas colonies inspired by France and the United States of America saw to wrestle control from a debilitated Metropolis, that demanded more taxes to rebuild itself after the Napoleonic period disasters. Many continental armies were sent to Central America and South America which proved to be futile and too late. The former Empire lost an important artery of its Power and with it the wealth in revenues on which have become too dependent over centuries, to reform the Military into a modern and standing national force however conscription was adopted.

At the same time right after, and as consequence of the regional grievances brewing for decades against the Centralization of Government that the Bourbons brought from France, surfacing during and after the Napoleonic wars that made it more evident and taking sides within the dynastic wars that took place mainly within the peninsula, it broke Spain into more military woes to reform not just the Military but its whole Administrative and Social structure. As consequence of these internal conflicts, and the weakness of a Central net structures of government under the Monarch, many generals with political careers intent would interrupt in the Public Life in multiple pronunciamientos for the rest of the century until the Second Restoration of the Bourbons in Spain, that will form part of the pervasive Cultural mentality of the new professional body of officers forming into the High command and of a more or less permissive Society at large, expecting these or financing and backing these military irruptions in Civil government. This Cultural tacit expectation of "special emergency interventions" from the military will pervade well into the first third of the XX century, ending up in the Spanish Civil War between factions of the Military and the whole Social reconfiguration of the Nation in all its sections and seams, from the State itself and its geographic entirety down to the families and individuals split by it.

Further information: see the Spanish-American War in 1998 against the United States and Spanish War in Cuba and lost of Empire

Second Republic (1931-36)

During the Second Spanish Republic, the Spanish government enlisted over a ten million men to the army.

The Spanish Army under the Francoist Regime (1939-1975)

This period can be divided in four phases:[13]

- 1939-1945: Second World War

- 1945-1954: International Isolation (lack of means)

- 1954-1961: Agreement with the United States (a certain improvement in means and capabilities)

- 1961-1975: Development plans (economic basis for the modernisations that follows in the 1970s and 1980s).

Second World War

At the end of the Civil War, the Spanish (Francoist) Army counted with 1,020,500 men, in 60 Divisions.[14] During the first year of peace, Franco dramatically reduced the size of the Spanish Army to 250,000 in early 1940, with most soldiers two-year conscripts.[15] A few weeks after the end of the war, the eight traditional Military Regions (Madrid, Sevilla, Valencia, Barcelona, Zaragoza, Burgos, Valladolid, La Coruña) were reestablished. In 1944 a ninth Military Region, with HQ in Granada, was created.[14] The Air Force became an independent service, under its own Air Ministry.

Concerns about the international situation, Spain's possible entry into World War II, and threats of invasion led him to undo some of these reductions. In November 1942, with the Allied landings in North Africa and the German occupation of Vichy France bringing hostilities closer than ever to Spain's border, Franco ordered a partial mobilization, bringing the army to over 750,000 men.[15] The Air Force and Navy also grew in numbers and in budgets, to 35,000 airmen and 25,000 sailors by 1945, although for fiscal reasons Franco had to restrain attempts by both services to undertake dramatic expansions.[15]

During the Second World War, the Spanish Army had eight Army Corps, with two or three Infantry Division each. Additionally, there were two Army Corps in Northern Africa, the Canary Islands General Command and the Balearic Islands General Command, one Cavalry Division and the Artillery's General Reserve. In 1940 a Reserve Group, with three Divisions, was created.[14]

International Isolation

At the end of the Second World War, the Spanish Army counted 22,000 officers, 3,000 NCO and almost 300,000 soldiers. The equipment dated from the Civil War, with some systems produced in Germany during the World War. Doctrine and Training were obsolete, as they had not incorporated the teachings of the Second World War. This situation lasted until the agreements with the United States in September 1953.[13]

Agreement with the United States (Barroso Reform, 1957)

After the signature of the military agreement with the United States in 1953, the assistance received from Washington allowed Spain to procure more modern equipment and to improve the country's defence capabilities. More than 200 Spanish officers and NCOs received specialised training in the United States each year under a parallel program. With the Barroso Reform (1957), the Spanish Army abandoned the organisation inherited from the Civil War to adopt the United States' pentomic structure. In 1958 three experimental pentomic Infantry Divisions were created (Madrid, Algeciras, Valencia). In 1960, five more pentomic Infantry Divisions (Gerona, Málaga, Oviedo, Vigo, Vitoria) and four mountain Divisions were created. All in all, after the Barroso Reform, the Spanish Army had 8 pentomic Infantry Divisions, four Mountain Divisions, one Armoured Division, one Cavalry Division, three independent Armoured Brigades and three Field Artillery Brigades.[13]

Years of Economic Development (Menéndez Tolosa Reform, 1965)

The 1965 Reforms were inspired by contemporary French organisation and Doctrine of the era. The Army was grouped into two basic categories: the Immediate Intervention Forces (Field Army) and the Operational Defence Forces (Territorial Army) and were divided into the following:

- The IIF (FA) had the mission of defending the Pyrenean and the Gibraltar frontiers and of fulfilling Spain's security commitments abroad and thus were composed of the following:

- Armoured Division, with two Brigades

- Mechanised Division, with two Brigades

- Motorized Division, with two Brigades

- Parachute Brigade (raised 1973)

- Airborne Brigade

- Armored Cavalry Brigade

- Army Corps support units

- ODF (TA) units had the missions of maintaining security in the regional commands and of reinforcing the Civil Guard) and the police against subversion and terrorism categorized into:

- 9 independent TA Infantry Brigades (one in every Military Region), with two Infantry Battalions each,

- 2 TA Mountain Divisions,

- 1 Mountain Reserve of the Army High Command (TA),

- The Canary Islands, Balearic Islands, Ceuta and Melilla commands, with their respective TA units including the Regulares (6 Groups later reduced to 4) and the Spanish Legion (4 Tercios),

- and the Army General Reserve Command, composed of TA units working as the reserve force of the Army and are the equivalent to the United States Army Reserve.[13]

During the last years of the Francoist regime, contemporary weapons were ordered for the Spanish Army. In 1973, the military education system was reformed in depth, in order to make its structure and objectives similar to those existing in the civilian universities. It was during this time that the Spanish Army fought in the campaigns in what is now Western Sahara against Arab forces in the area who agitated for the end of Spanish colonial rule.

The Spanish Army under King Juan Carlos I

Initial years (1975-1989)

Three main events characterise this period: creation of a single Ministry of Defence (1977) to replace the three existing military ministries (Army, Navy and Air Ministries), the failed coup d'état in February 1981 and the accession to NATO in 1982.

The Army modernisation program (META plan) was done between 1982 and 1988 in order for Spain to achieve full compliance with NATO standards.[16] When the plan was completed the following results were achieved:

- Military regions in the mainland were reduced from 9 to 6.

- The IIF (FA) and the ODF (TA) were merged into one single structure.

- The number of Brigades was reduced from 24 to 15.

- Personnel numbers were reduced from 279,000 to 230,000.

After the end of the Cold War (1989-present)

The end of the Cold War came with the reduction of the term of military service for conscripts until its complete abolition in 2001[17] and the increasing participation of Spanish forces in multinational peacekeeping operations abroad[18] are the main drivers for changes in the Spanish Army after 1989. Three reorganisation plans were implemented since: the RETO plan (1990), the NORTE plan (1994)[19] and the Instruction for Organisation and Operation of the Army (IOFET) 2005.

Today

Personnel

In 2001, when compulsory military service was still in effect, the army was about 135,000 troops (50,000 officers and 86,000 soldiers). Following the suspension of conscription the Spanish Army became a fully professionalised volunteer force and by 2008 had a personnel strength of 75,000.[20] In case of a wartime emergency, an additional force of 80,000 Civil Guards comes under the Ministry of Defence command.

Equipment

Weapons

- Heckler & Koch USP - 9 mm pistol Standard weapon.

- Heckler & Koch MP5 - 9 mm submachine gun Special Operations Forces.

- Heckler & Koch G36 - 5.56 mm assault rifle. Without integral red dot sight, Spanish variants use a Picatinny Rail to mount an EoTech holographic sight

- Heckler & Koch G36KE and G36CE - 5.56 mm assault rifle Special Operations Forces.

- Heckler & Koch HK417 - 7.62 mm NATO assault rifle Special Operations Forces.

- Rheinmetall MG3 - 7.62 mm NATO medium machine gun

- Heckler & Koch MG4 - 5.56 mm light machine gun (standard LMG)

- Browning M2 HB - 12.70 mm heavy machine gun

- SB LAG 40 grenade Launcher

- Instalaza Alhambra-DO hand grenade

- Instalaza C-100 Alcotán - 100 mm anti-tank rocket launcher

- Instalaza C-90 CR (M3) - 90 mm disposable anti-tank rocket launcher

- Spike - anti-tank missile launcher

- Milan - anti-tank missile launcher

- TOW 2 - anti-tank missile launcher

- Barrett M95 - 12.7 mm heavy sniper rifle

- Accuracy International Arctic Warfare - 7.62 mm sniper rifle

- ECIA L65/60 60 mm light mortar

- ECIA L65/81 mortar - 81 mm medium mortar

- ECIA L65/105 mortar - 105 mm medium mortar

- ECIA L65/120 mortar - 120 mm heavy mortar

Combat vehicles

- 219 Leopardo 2E (A6) Main Battle Tank

- 108 Leopard 2 A4 Main Battle Tank ( 54 in reserve )

- 99 VRC-105B1 Centauro wheeled tank-destroyer

- 4 VCREC Centauro

- 374 Pizarro infantry fighting vehicles in five versions

- 500+ M113 armored personnel carriers in seven versions

- 648 BMR-M1 medium six-wheeled APC

- 135 VEC-M1 cavalry scout vehicle

- 90 TOM Bv206S tracked vehicle

- 185 IVECO LMV Lince 4WD tactical vehicle (575 total order)

- 100 RG-31 Mk5E Nyala (MRAP) 4WD tactical vehicle (MRAP)

- 10 Cardom Recoil Mortar System (RMS)

- 6 Husky 2G (mine detection system)

- URO VAMTAC, all terrain 4x4 tactical vehicle (more than 1,500)

- Santana Anibal, an all terrain 4x4 utility vehicle (more than 1,500)

- Iveco Euro Cargo all terrain utility vehicle

- Iveco M250W.37

- VEMPAR Tactic Heavy Lorry 450HP, 20t cargo lorry

Artillery

- M109A5 - 155/39 mm self-propelled howitzer, as the M109A5(+96)

- 155/52 APU SBT - 155/52 mm howitzer (84)

- L-118A1 - 105/37 mm light field howitzer (59) with Base Bleed (range 21 km) by Expal

- OERLIKON GDF-005 35/90 35 mm Anti-aircraft artillery piece (92)

- Raytheon MIM-104 Patriot - Surface-to-Air missile system (3 batteries)

- Skyguard-Aspide - Surface-to-Air missile system (13)

- NASAMS - Surface-to-Air missile system (8)

- MBDA SATCP Mistral missile - Anti-aircraft infrared homing missile system (168)

Aircraft

| Type | Origin | Class | Role | Introduced | In service | Total | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agusta-Bell 212 | Italy | Rotorcraft | Utility | 6 | [21] | ||

| Bell UH-1H Iroquois | USA | Rotorcraft | Utility | 14 | [21] | ||

| Boeing CH-47D Chinook | USA | Rotorcraft | Transport | 17 | [21] | ||

| Bölkow BO-105 | Germany | Rotorcraft | Attack | 14 | [21] | ||

| Eurocopter AS332B1 Super Puma | France | Rotorcraft | Transport | 15 | [21] | ||

| Eurocopter AS532UL Cougar | France | Rotorcraft | Transport | 14 | [21] | ||

| Eurocopter EC-135 | Germany | Rotorcraft | Trainer/utility | 14 | [21] | ||

| Eurocopter Tigre | France/Germany/Spain | Rotorcraft | Attack | 9 | 9 on order[21] | ||

| NHI NH90 | France/Germany | Rotorcraft | Transport | 1 | 21 on order[21] |

Unmanned aerial vehicles

- 4 x INTA SIVA

- 4 x IAI Searcher MK II J

- 27 x RQ-11 Raven (mini UAV)

Formation and structure

For the current structure of the Spanish Army see the article Structure of the Spanish Army.

Commanders in Chief of the Spanish Army

Army Ministers

Source: es:Ministerio del Ejército

- Lieutenant General José Enrique Varela Iglesias (1939-1942)

- Lieutenant General Carlos Asensio Cabanillas (1942-1945)

- Lieutenant General Fidel Dávila Arrondo (1945-1951)

- Lieutenant General Agustín Muñoz Grandes (1951-1957)

- Lieutenant General Antonio Barroso y Sánchez-Guerra (1957-1962)

- Lieutenant General Pablo Martín Alonso (1962-1964)

- Lieutenant General Camilo Menéndez Tolosa (1964-1969)

- Lieutenant General Juan Castañón de Mena (1969-1973)

- Lieutenant General Francisco Coloma Gallegos (1973-1975)

- Lieutenant General Félix Álvarez-Arenas y Pacheco (1975-1977)

Chiefs of the Army Staff

- Lieutenant General José Vega Rodríguez (1976-1978)[22]

- Lieutenant General Tomás de Liniers y Pidal (1978-1979)[22]

- Lieutenant General José Gabeiras Montero (1979-1982)[22]

- Lieutenant General Ramón de Ascanio y Togores (1982-1984)[22]

- Lieutenant General José María Sáenz de Tejada y Fernández de Bobadilla (1984-1986)[22]

- Lieutenant General Miguel Íñiguez del Moral (1986-1990)[22]

- Lieutenant General Ramón Porgueres Hernández (1990-1994)[22]

- Lieutenant General José Faura Martín (1994-1998)[22]

- Lieutenant General Alfonso Pardo de Santayana y Coloma(1998-2003)[22]

- Army General Luis Alejandre Sintes (2003-2004)[22]

- Army General José Antonio García González (2004-2006)[22]

- Army General Carlos Villar Turrau (2006-2008)[22]

- Army General Fulgencio Coll Bucher (2008-2012)[22]

- Army General Jaime Domínguez Buj (2012-2017)[23]

- Army General Francisco Javier Varela Salas (2017-)[2]

Uniforms

|

|

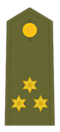

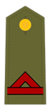

Ranks and insignia

The military ranks of the Spanish army are as follows below. For a comparison with other NATO ranks see Ranks and Insignia of NATO. Ranks are wore on the cuff, sleeves and shoulders of all army uniforms, but differ by the type of the uniform being used.

| NATO code | OF-10 | OF-9 | OF-8 | OF-7 | OF-6 | OF-5 | OF-4 | OF-3 | OF-2 | OF-1 | OF(D) | Student officer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Edit) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Capitán general[24] The King only |

General de Ejército | Teniente general | General de división | General de brigada | Coronel | Teniente coronel | Comandante | Capitán | Teniente | Alférez | Caballero Alférez Cadete | Alumno repetidor | Alumno 2º | Alumno 1º | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NATO Code | OR-9 | OR-8 | OR-7 | OR-6 | OR-5 | OR-4 | OR-3 | OR-2 | OR-1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Edit) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Suboficial mayor | Subteniente | Brigada | Sargento primero | Sargento | Cabo mayor | Cabo primero | Cabo | Soldado de primera | Soldado | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Officer ranks

- Caballero Alférez Cadete - lit. Gentleman/Knight Knight Cadet

- Alférez - lit. Knight, (Ensign)

- Teniente - Lieutenant

- Capitán - Captain

- Comandante - Commandant (lit. Commander), Major

- Teniente Coronel - Lieutenant Colonel

- Coronel - Colonel

- General de Brigada - Brigade General

- General de División - Divisional General

- Teniente General - Lieutenant General

- General de Ejército - Army General

- Capitán General - Captain General

Ranks of non-commissioned officers and enlisted

- Soldado - Soldier

- Soldado de Primera - Soldier First Class

- Cabo - Corporal

- Cabo Primero - First Corporal

- Cabo Mayor - Corporal Major

- Sargento - Sergeant

- Sargento Primero - First Sergeant

- Brigada - Warrant Officer

- Subteniente- Warrant Officer

- Suboficial Mayor - Sub-officer Major

See also

- Spanish Armed Forces

- Army of Spain (Peninsular War)

- NATO

- FAMET

- Spanish legion

- Regulares

- Spanish Republican Army

- Coats of Arms, Badges and Emblems of the Spanish Army

References

- ↑ "España Hoy 2016-2016". lamoncloa.gob.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- 1 2 New chiefs of Army, Navy and Air Force. Ministery of Defence (Spain). Retrieved 31 March 2017

- ↑ Davies, 1961

- ↑ Elton, p. 181.

- ↑ Anderson, p. 17.

- ↑ Meade, p. 180.

- ↑ Anderson, pp. 109–10.

- ↑ Comparative Atlas of Defence in Latin America / 2008 Edition, p.42 (PDF)

- ↑ Charles J. Esdaile, The Spanish Army in the Peninsular War (1988)

- ↑ Philip Haythornthwaite; Christa Hook (2013). Corunna 1809: Sir John Moore's Fighting Retreat. Osprey. pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Russell Crandall (2014). America's Dirty Wars: Irregular Warfare from 1776 to the War on Terror. Cambridge UP. p. 21.

- ↑ Otto Pivka, Spanish Armies of the Napoleonic Wars (Osprey Men-at-Arms, 1975)

- 1 2 3 4 PUELL DE LA VILLA, Fernando (2010). "El devenir del Ejército de Tierra (1945-1975)". In Fernando Puell de la Vega y Sonia Alda Mejías (ed.). Los Ejércitos del franquismo. Madrid: IUGM-UNED. 2010. Pp. 63-96.

- 1 2 3 MUÑOZ BOLAÑOS, Roberto (2010). "La institución militar en la posguerra (1939-1945)". In Fernando Puell de la Vega y Sonia Alda Mejías (ed.). Los Ejércitos del franquismo. Madrid: IUGM-UNED. 2010. Pp. 15-55.

- 1 2 3 Bowen, Wayne H.; José E. Álvarez (2007). A Military History of Modern Spain. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-275-99357-3.

- ↑ YÁRNOZ, Carlos (February 10, 1983). "El plan de modernización del Ejército de Tierra renovará completamente la estructura actual". elpais.com. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ↑ See an announcement by the Minister of Defence

- ↑ http://www.defensa.gob.es/en/areasTematicas/misiones/%20

- ↑ CERVERA ARTEAGA, Eva. "Retrospectiva de tres décadas en el Ejército de Tierra español". Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ↑ Estadística de Personal Militar de Complemento , Militar Profesional de Tropa y Marinería y Reservista Voluntario (PDF)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "World Air Forces 2016". Flightglobal: p. 29. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 La transformación de los ejércitos españoles (1975-2008). Madrid: UNED. 2009. p. 366.

- ↑ Real Decreto 1164/2012, de 27 de julio (PDF)

- ↑ Title; Honorary or posthumous rank; war time rank; ceremonial rank

Bibliography

- Instruction no. 59/2005, of 4 April 2005, from the chief of the army staff on army organisation and function regulations, published in B.O.D. NO. 80 of 26 April 2005

- Lehardy, Diego, Spanish Army in a difficult phase of its transformation, RID magazine, July 1991.

External links and further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Army of Spain. |

- Home page of the Spanish Land Army (in English)

- Recruitment page (in Spanish)

- The Spanish Military Forum