Spanish Navy

| Spanish Navy Armada Española [1] | |

|---|---|

|

Emblem of the Spanish Navy[2] | |

| Active | 13th century — present |

| Country |

|

| Branch | Spanish Armed Forces |

| Type | Navy |

| Size |

20,838 personnel (2016)[3] 131 ships 59 aircraft[4] |

| Part of | Ministry of Defence |

| Garrison/HQ |

|

| Patron | Virgen del Carmen |

| March | Himno de la Escuela Naval (José María Pemán) |

| Anniversaries | 16 July |

| Website |

www |

| Commanders | |

| Commander in Chief | King Felipe VI |

| Admiral Chief of the Naval Staff | Admiral Teodoro E. López Calderón[5] |

| Insignia | |

| Naval jack |

|

| Naval Ensign |

|

| Aircraft flown | |

| Attack | Harrier AV8+ |

| Helicopter | Sikorsky SH60 SeaHawk |

| Cargo helicopter | Sikorsky SeaKing |

| Multirole helicopter | Augusta Bell 212 |

| Patrol | P-3 Orion |

| Trainer | Hughes 500 |

| Transport | Cessna Citation |

The Spanish Navy (Spanish: Armada Española), is the maritime branch of the Spanish Armed Forces and one of the oldest active naval forces in the world. The Spanish navy was responsible for a number of major historic achievements in navigation, the most famous being the discovery of America and the first global circumnavigation by Magellan and Elcano. For several centuries, it played a crucial logistical role in the Spanish Empire and defended a vast trade network across the Atlantic Ocean between the Americas and Europe and across the Pacific Ocean between Asia and the Americas.

The Spanish Navy was one of the most powerful maritime forces in the world in the 16th and 17th centuries and possibly the world`s largest navy at the end of the 16th century and in the early 17th century. Reform under the Bourbon dynasty improved its logistical and military capacity in the 18th century, for most of which Spain possessed the world's third largest navy. In the 19th century, the Spanish Navy built and operated the first military submarine, made important contributions in the development of destroyer warships, and achieved the first global circumnavigation by an ironclad vessel.

Currently, the Spanish 'Armada' is the third largest navy in Europe, after the British Royal Navy and the French Navy, and the sixth in the world ranking.

The main bases of the Spanish Navy are located in Rota, Ferrol, San Fernando and Cartagena.

History

Origins: the Middle Ages

The roots of the modern Spanish navy date back to before the unification of Spain. By the late Middle Ages, the two principal kingdoms that would later combine to form Spain, Aragon and Castile, had developed powerful fleets. Aragon possessed the third largest navy in the late medieval Mediterranean, although its capabilities were exceeded by those of Venice and (until overtaken in the 15th century by those of Aragon) Genoa. In the 14th and 15th centuries, these naval capabilities enabled Aragon to assemble the largest collection of territories of any European power in the Mediterranean, encompassing the Balearics, Sardinia, Sicily, southern Italy and, briefly, the Duchy of Athens. Castile meanwhile used its naval capacities to conduct its reconquista operations against the Moors, capturing Cadiz in 1232 and also to help the French Crown against its enemies in the Hundred Years' War. In 1402, a Castilian expedition led by Juan de Bethencourt conquered the Canary Islands for Henry III of Castile.

In the 15th century, Castile entered into a race of exploration with Portugal, the country that inaugurated the European Age of Discovery. In 1492, two caravels and a carrack, commanded by Christopher Columbus, arrived in America, on an expedition that sought a westward oceanic passage across the Atlantic, to the Far East. This began the era of trans-oceanic trade routes, pioneered by the Spanish in the seas to the west of Europe and the Portuguese to the east.

The Habsburg era

Following the discovery of America and the settlement of certain Caribbean islands, such as Cuba, Spanish conquistadors Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro were carried by the Spanish navy to the mainland, where they conquered Mexico and Peru respectively. The navy also carried explorers to the North American mainland, including Juan Ponce de León and Álvarez de Pineda, who discovered Florida (1519) and Texas (1521) respectively. In 1519, Spain sent out the first expedition of world circumnavigation in history, which was put in the charge of the Portuguese Commander Ferdinand Magellan. Following the death of Magellan in the Philippines, the expedition was completed under the command of Juan Sebastián Elcano in 1522. In 1565, a follow-on expedition by Miguel López de Legazpi was carried by the navy from New Spain (Mexico) to the Philippines via Guam in order to establish the Spanish East Indies, a base for trade with the Orient. For two and a half centuries, the Manila galleons operated across the Pacific linking Manila and Acapulco. Until the early 17th century, the Pacific Ocean. Aside from the Marianas and Caroline Islands, several naval expeditions also discovered the Tuvalu archipelago, the Marquesas, the Solomon Islands and New Guinea in the South Pacific. In the quest for Terra Australis, Spanish explorers in the 17th century also discovered the Pitcairn and Vanuatu archipelagos. Most significantly, from 1565 Spanish fleets explored and colonised the Philippine archipelago, the Spanish East Indies.

After the unification of its kingdoms under the House of Habsburg, Spain maintained two largely separate fleets, one consisting chiefly of galleys for use in the Mediterranean and the other of sailing ships for the Atlantic, successors to the Aragonese and Castilian navies respectively. This arrangement continued until superseded by the decline of galley warfare during the 17th century. The completion of the Reconquista with the conquest of the Kingdom of Granada in 1492 had been followed by naval expansion in the Mediterranean, where Spain seized control of almost every significant port along the coast of North Africa west of Cyrenaica, notably Melilla (captured 1497), Mers El Kébir (1505), Oran (1509), Algiers (1510) and Tripoli (1511), which marked the furthest point of this advance. However, the hinterlands of these ports remained under the control of their Muslim and Berber inhabitants, and the expanding naval power of the Ottoman Empire brought about a major Islamic counter-offensive, which embroiled Spain in decades of intense warfare for control of the western Mediterranean. (Algiers and Tripoli would be lost to the Ottomans later in the 16th century.) From the 1570s, the Dutch Revolt increasingly challenged Spanish sea power, producing powerful rebel naval forces that attacked Spanish shipping and in time made Spain's sea communications with its possessions in the Low Countries difficult. Most notable of these attacks was the Battle of Gibraltar in 1607, in which a Dutch squadron destroyed a fleet of galleons at anchor in the confines of the bay. This naval war took on a global dimension with actions in the Caribbean and the Far East, notably around the Philippines. Spain's response to its problems included the encouragement of privateers based in the Spanish Netherlands and known from their main base as Dunkirkers, who preyed on Dutch merchant ships and fishing trawlers.

At the Battle of Lepanto (1571), the Holy League, formed by Spain, Venice, the Papal States and other Christian allies, inflicted a great defeat on the Ottoman Navy, stopping Muslim forces from gaining uncontested control of the Mediterranean.

In the 1580s, the conflict in the Netherlands drew England into war with Spain, creating a further menace to Spanish shipping. The effort to neutralise this threat led to a disastrous attempt to invade England in 1588. This defeat led to a reform of fleet operations. The navy at this time was not a single operation but consisted of various fleets, made up mainly of armed merchantmen with escorts of royal ships. The Armada fiasco marked a turning point in naval warfare, where gunnery was now more important than ramming and boarding and so Spanish ships were equipped with purpose built naval guns. During the 1590s, the expansion of these fleets allowed a great increase in the overseas trade and massive increase in the importation of luxuries and silver. Nevertheless, inadequate port defences allowed an Anglo-Dutch force to raid Cadiz in 1596, and though unsuccessful in its objective of capturing the silver from the just returned convoy, was able to inflict great damage upon the city. Port defences at Cadiz were upgraded and all attempts to repeat the attack in the following centuries would fail.

Meanwhile, Spanish ships were able to step up operations in the English Channel, the North Sea and towards Ireland. They were able to capture many enemy ships, merchant and military, in the early decades of the 17th century and provide military supplies to Spanish armies in France and the Low Countries and to Irish rebels in Ireland.

By the middle of the 17th century, Spain had been drained by the vast strains of the Thirty Years' and related wars and began to slip into a slow decline. During the middle to late decades of the century, the Dutch, English and French were able to take advantage of Spain's shrinking, run-down and increasingly underequipped fleets. Military priorities in continental Europe meant that naval affairs were increasingly neglected. The Dutch took control of the smaller islands of the Caribbean, while England conquered Jamaica and France the western part of Santo Domingo. These territories became bases for raids on Spanish New World ports and shipping by pirates and privateers. The Spanish concentrated their efforts in keeping the most important islands, such as Cuba, Puerto Rico and the majority of Santo Domingo, while the system of treasure fleets, despite being greatly diminished, was rarely defeated in safely conveying its freight of silver and Asian luxeries across the Atlantic to Europe. Only two such convoys were ever lost to enemy action with their cargo, one to a Dutch fleet in 1628 and another to an English fleet in 1656. A third convoy was destroyed at anchor by another English attack in 1657, but it had already unloaded its treasure.

By the time of the wars of the Grand Alliance (1688-97) and the Spanish Succession (1702-14), the Habsburg regime had decided that it was more cost effective to rely on allied fleets, Anglo-Dutch and French respectively, than to invest in its own fleets.

The Bourbon era

The War of the Spanish Succession arose after the establishment on the Spanish throne of a House of Bourbon king, following the extinction of the Spanish Habsburg line. The internal division between supporters of a Habsburg and those of a Bourbon king led to a civil war and ultimately to the loss of Sicily, Sardinia, Minorca and Gibraltar. Gibraltar and Minorca were occupied by British forces fighting under the Spanish flag of Habsburg contender Charles VI. Minorca was ultimately surrendered to Spain years later. During the War of Spanish Succession, Spain's possessions in the Netherlands and mainland Italy were also ceded.

Attempting to reverse the losses of the previous war, in the War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718–20) the Spanish navy successfully convoyed armies to invade Sicily and Sardinia, but the escort fleet was destroyed by the British in the Battle of Cape Passaro and the Spanish invasion army was defeated in Italy by the Austrians. A major program to renovate and reorganise the run-down navy was begun. A secretaría (ministry) of the army and navy had been established by the Bourbon regime as early as 1714; which centralized the command and administration of the different fleets. Following the war of Quadruple Alliance, a program of rigorous standardization was introduced in ships, operations, and administration. Given the needs of its empire, Spanish warship designs tended to be more orientated towards long-range escort and patrol duties than for battle. A major reform of the Spanish navy was initiated, updating its ships and administration, which was helped by French and Italian experts, although Spaniards, most notably Antonio Castaneta, soon rose to prominence in this work, which made Spain a leader in warship design and quality again, as was demonstrated by ships like the Princesa. A major naval yard was established at Havana, enabling the navy to maintain a permanent force in the Americas for the defence of the colonies and the suppression of piracy and smuggling.

During the War of the Polish Succession (1733–38), a renewed attempt to regain the lost Italian territories for the Bourbon dynasty was successful; with the French as allies and the British and Dutch neutral, Spain launched a campaign by sea and retook Sicily and southern Italy from Austria. In the War of Jenkins' Ear, the navy showed it was able to maintain communications with the American colonies and resupply Spanish forces in Italy in the face of British naval opposition. The navy played an important part in the decisive Battle of Cartagena de Indias in modern-day Colombia, where a massive British invasion fleet and army were defeated by a smaller Spanish force commanded by able strategist Blas de Lezo. This Spanish victory prolonged Spain's supremacy in the Americas until the early 19th century. The program of naval renovation was continued and by the 1750s the Spanish navy had outstripped the Dutch to become the third most powerful in the world, behind only those of Britain and France.

Joining France against Britain near the end of the Seven Years' War (1756–63), the navy failed to prevent the British capturing Havana, during which the Spanish squadron present was also captured. In the American War of Independence (1775–83), the Spanish navy was essential to the establishment, in combination with the French and Dutch navies, of a numerical advantage that stretched British naval resources. They played a vital role, along with the French and Dutch, in maintaining military supplies to the American rebels. The navy also played a key role in the Spanish army led operations that defeated the British in Florida. The bulk of the purely naval combat on the allied side fell to the French navy, although Spain achieved lucrative successes with the capture of two great British convoys meant for the resupply of British forces and loyalists in North America. Joint operations with France resulted in the capture of Minorca but failed in the siege of Gibraltar.

Having initially opposed France in the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802), Spain changed sides in 1796, but defeat by the British a few months later in the Battle of Cape St Vincent (1797) and Trinidad (1798) was followed by the blockade of the main Spanish fleet in Cadiz. The run down of naval operations had as much to do with the confused political situation in Spain as it had to do with the blockade. The British blockade of Spain's ports was of limited success and an attempt to attack Cadiz was defeated; ships on special missions and convoys successfully evaded the Cadiz blockade and other ports continued to operate with little difficulty, but the main battle fleets were largely inactive. The blockade was lifted with the Peace of Amiens 1802. The war recommenced in 1804 and ended in 1808 when the Spain and the United Kingdom became allied against Napoleon. As in the first part, Cadiz was blockaded and Spanish naval activity was minimal. The most notable event was Spanish involvement in the Battle of Trafalgar under French leadership. This resulted in the Spanish navy losing eleven ships-of-the-line or over a quarter of its line-of-battle ships. After Spain became allied with the United Kingdom in 1808 in its war of independence, the Spanish navy joined the war effort against Napoleon.

The navy in decline

The 1820s saw the loss of most of the Spanish Empire in the Americas. With the empire greatly reduced in size and Spain divided and unstable after its own war of independence, the navy lost its importance and shrank greatly.

During the Spanish–American War in 1898, a badly supported and equipped Spanish fleet of four armored cruisers and two destroyers was overwhelmed by numerically and technically superior forces (three new battleships, one new second class battleship, and one large armored cruiser) as it tried to break out of an American blockade in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba. Admiral Cervera's squadron was overrun in an attempt to break a powerful American blockade off Cuba.

In the Philippines, a squadron, made up of ageing ships, including some obsolete cruisers, had already been sacrificed in a token gesture in Manila Bay. The Battle of Manila Bay took place on 1 May 1898, during the Spanish–American War. The American Asiatic Squadron under Commodore George Dewey engaged and destroyed the Spanish Pacific Squadron under Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasarón. The engagement took place in Manila Bay in the Philippines, and was the first major engagement of the Spanish–American War. This war marked the end for the Spanish Navy as a global maritime force.

At the end of the 19th century, the Spanish Navy adopted the Salve Marinera, a hymn to the Virgin Mary as Stella Maris, as its official anthem.

The 20th and 21st centuries

During the Rif War in Morocco, the Spanish navy conducted operations along the coast, including the Alhucemas landing in 1925, the first air-naval landing of the world. At that time, the Navy developed a Naval Aviation branch, the Aeronáutica naval. In 1931, following the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic, the Navy of the Spanish Kingdom became the Spanish Republican Navy. Admiral Aznar's casual comment: "Do you think it was a little thing what happened yesterday, that Spain went to bed as a monarchy and rose as a republic" became instantly famous, going quickly around Madrid and around Spain, making people accept the fact and setting a more relaxed mood.[6] The Spanish Republican Navy introduced a few changes in the flags and ensigns, as well as in the navy officer rank insignia.[7] The executive curl (La coca) was replaced by a golden five-pointed star and the royal crown of the brass buttons and of the officers' breastplates (La gola) became a mural crown. The Spanish Republican Navy became divided after the coup of July 1936 that led to the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). The fleet's two small dreadnoughts, one heavy cruiser, one large destroyer and half a dozen submarines and auxiliary vessels were lost in the course of the conflict.

Since the mid-20th century, the Spanish Navy began a process of reorganization to once again become one of the major navies of the world. After the development of the Baleares-class frigates based on the US Navy's Knox class, the Spanish Navy embraced the American naval doctrine.[8] Spain is a member of NATO in 1982 and the Armada Española has taken part in many coalition peacekeeping operations, from SFOR to Haiti and other locations around the world. Today's Armada is a modern navy with a carrier group, a modern strategic amphibious ship (which has recently replaced a dedicated aircraft carrier), modern frigates (F-100 class) with the Aegis Combat System, F-80-class frigates, minesweepers, new S-80-class submarines, amphibious ships and various other ships, including oceanographic research ships.

The Armada's special operations and unconventional warfare capability is embodied in the Naval Special Warfare Command (Mando de Guerra Naval Especial), which is under the direct control of the Admiral of the Fleet. Two units operate under this command:

- The Special Operations Unit (Unidad de Operaciones Especiales (UOE)): Special operations unit trained in maritime counter-terrorism, combat diving and swimming, coastal infiltration, ship boarding, direct action, and special reconnaissance.

- The Combat Diver Unit (Unidad Especial de Buceadores de Combate (UEBC)): Specialized combat diving unit trained in underwater demolitions and hydrographic reconnaissance.

Armada officers receive their education at the Spanish Naval Academy (ENM). They are recruited through two different methods:

- Militar de Complemento: Similar to the U.S. ROTC program, students are college graduates who enroll in the navy. They spend a year at the Naval Academy and then are commissioned as ensigns and Marine second lieutenants. This path is growing in prestige. Their career stops at the rank of commander (for the Navy) and for the Marines, lieutenant colonel.

- Militar de Carrera: Students spend one year in the Naval Academy if they apply to the Supply Branch or the Engineering Branch, and five years if they apply as General Branch or Marines, receiving a university degree-equivalent upon graduation and being commissioned as ensigns and Marine second lieutenants.

Current status

Subordinate to the Spanish Chief of Naval Staff, stationed in Madrid, are four area commands: the Cantabrian Maritime Zone with its headquarters at Ferrol on the Atlantic coast; the Straits Maritime Zone with its headquarters at San Fernando near Cadiz; the Mediterranean Maritime Zone with its headquarters at Cartagena; and the Canary Islands Maritime Zone with its headquarters at Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. Operational naval units are classified by mission and assigned to either the combat forces, the protective forces, or the auxiliary forces. Combat forces are given the tasks of conducting offensive and defensive operations against potential enemies and for assuring maritime communications. Their principal vessels included two carrier groups, naval aircraft, transports, landing vessels, submarines, and missile-armed fast attack craft. Protective forces have the mission of securing maritime communications over both ocean and coastal routes, securing the approaches to ports and maritime terminals. Their principal components are destroyers, frigates, corvettes, and minesweepers. It also has marine units for the defense of naval installations. Auxiliary forces are responsible for transportation and provisioning at sea and has diverse tasks like coast guard operations, scientific work, and maintenance of training vessels. In addition to supply ships and tankers, the force included destroyers and a large number of patrol craft.

Until February 2013, when it was decommissioned because of budget cuts,[9] the second largest vessel of the Armada was the aircraft carrier Principe de Asturias, which entered service in 1988 after completing sea trials. Built in Spain, it was designed with a "ski-jump" takeoff deck. Its complement was 29 AV-8 Harrier II vertical (or short) takeoff and landing (V/STOL) aircraft or 16 helicopters designed for antisubmarine warfare and to support marine landings.

As of 2012, the Armada has a strength of 20,800 personnel.[10]

Infantería de Marina

The Infantería de Marina is the marine infantry of the Spanish Navy. It has a strength of 11,500 troops and is divided into base defense forces and landing forces. One of the three base defense battalions is stationed with each of the Navy headquarters. "Groups" (midway between battalions and regiments) are stationed in Madrid and Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. The Tercio (fleet — regiment equivalent) is available for immediate embarkation and based out of San Fernando. Its principal weapons include light tanks, armored personnel vehicles, self-propelled artillery, and TOW and Dragon antitank missiles.

Equipment

Ships and submarines

As of 2016, there are approximately 78 vessels in service within the Navy, including minor auxiliary vessels. A breakdown includes; one amphibious assault ship (also used as an aircraft carrier), two amphibious transport docks, 11 frigates, three submarines, six mine countermeasure vessels, 23 patrol vessels and a number of auxiliary ships. The total displacement of the Spanish Navy is approximately 220,000 tonnes.[11]

Aircraft

The Spanish Naval Air Arm constitutes the naval aviation branch of the Spanish Navy.

| Type | Origin | Class | Role | Introduced | In service | Total | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agusta-Bell AB 212 | USA/Italy | Rotorcraft | Utility | 8 | [4] | ||

| Cessna Citation | USA | Jet | Utility | 4 | [4] | ||

| Hughes 500M | USA | Rotorcraft | Trainer | 6 | [4] | ||

| McDonnell Douglas AV-8B Harrier II | UK/USA | Jet | Multi-role | 13 | [4] | ||

| Sikorsky SH-3 Sea King | USA | Rotorcraft | Transport/AEW | 9 | 2 AEW[4] | ||

| Sikorsky SH-60 Seahawk | USA | Rotorcraft | Attack | 10 | [4] |

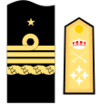

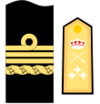

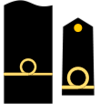

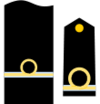

Current Rank structure

The officer ranks of the Spanish Navy are as follows below, (for a comparison with other NATO ranks, see Ranks and Insignia of NATO). Midshipmen are further divided into 1st and 2nd Classes and Officer Cadets 3rd and 4th Classes respectively.

| NATO Code | OF-10 | OF-9 | OF-8 | OF-7 | OF-6 | OF-5 | OF-4 | OF-3 | OF-2 | OF-1 | OF(D) | Student Officer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Capitán GeneralNote | Almirante General | Almirante | Vicealmirante | Contraalmirante | Capitán de Navío | Capitán de Fragata | Capitán de Corbeta | Teniente de Navío | Alférez de Navío | Alférez de Fragata | Guardiamarina 4º Curso | Guardiamarina 3º Curso | Alumno 2º Curso | Alumno 1º Curso | ||

| English translation | Captain General

Note Rank reserved to H.M. The Monarch of Spain. |

General Admiral | Admiral | Vice Admiral | Counter Admiral | Ship-of-the-line Captain | Frigate Captain | Corvette Captain | Ship-of-the-line lieutenant | Ship-of-the-line ensign | Frigate Ensign | Midshipman 4th Year | Midshipman 3rd Year | Officer Cadet 2nd year | Officer Cadet 1st year | |

| USN equivalent | Fleet Admiral | Admiral | Vice Admiral | Rear Admiral | Rear Admiral (lower half) or Commodore |

Captain | Commander | Lieutenant Commander | Lieutenant | Lieutenant (junior grade) | Ensign | Midshipman 4th Year | Midshipman 3rd Year | Officer Cadet 2nd year | Officer Cadet 1st year | |

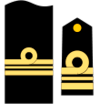

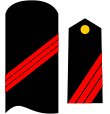

Ranks of Non-commissioned officers and Enlisted ratings

| NATO Code | OR-9 | OR-8 | OR-7 | OR-6 | OR-5 | OR-4 | OR-3 | OR-2 | OR-1 | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Edit) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Suboficial mayor | Subteniente | Brigada | Sargento primero | Sargento | Cabo mayor | Cabo primero | Cabo | Marinero de primera | Marinero | |||||||||||||||||||

| English equivalent | Sub-officer Major | Sublieutenant | Brigadier | First Sergeant | Sergeant | Corporal Major | First Corporal | Corporal | Seaman first class | Seaman | ||||||||||||||||||

| USN equivalent | Command Master Chief Petty Officer | Master Chief Petty Officer | Senior Chief Petty Officer | Chief Petty Officer | Petty officer, first class | Petty officer, second class | Petty officer, third class | Seaman | Seaman Apprentice | Seaman Recruit | ||||||||||||||||||

The article Spanish Navy Marines includes the rank insignia descriptions for this part of the Navy.

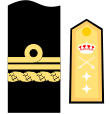

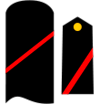

Current Staff Corps ranks and insignia

Naval Engineering Corps

Officer Corps

| NATO code | OF-7 | OF-6 | OF-5 | OF-4 | OF-3 | OF-2 | OF-1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Vicealmirante | Contraalmirante | Capitán de navío | Capitán de fragata | Capitán de corbeta | Teniente de navío | Alférez de navío | Alférez de Fragata | ||

Officer Cadets

| NATO Code | OF-D | Officer Cadets | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain |

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| Alférez de fragata

(Alumno de 5º) |

Guardiamarina de 2º

(Alumno de 4º) |

Guardiamarina de 1º

(Alumno de 3º) |

Aspirante de 2º

(Alumno de 2º) |

Aspirante de 1º

(Alumno de 1º) | |||||

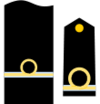

Naval Supply Corps

Officers of this corps sport army-styled ranks.

Officers

| Código OTAN | OF-7 | OF-6 | OF-5 | OF-4 | OF-3 | OF-2 | OF-1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| España |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| General de División | General de Brigada | Coronel | Teniente Coronel | Comandante | Capitán | Teniente | Alférez | ||

Officer Cadets

| Código OTAN | OF-D | Officer Cadets | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain |

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| Alférez

(Alumno 5º) |

Guardiamarina de 2º

(Alumno 4º) |

Guardiamarina de 1º

(Alumno 3º) |

Aspirante de 2º

(Alumno 2º) |

Aspirante de 1º

(Alumno 1º) | |||||

Organization

- The Fleet (Headquarters located at Rota)

- Projection Group "Alfa" located at Rota

- 1 LHD / multi-purpose warship and aircraft carrier Juan Carlos I (L61). 27,079 Tons.

- 2 LPD Galicia-class landing platform docks. 13,818 tons.

- 1 Replenishment ship Patiño (A14) (located at Ferrol). 17,045 tons.

- 1 Replenishment ship Cantabria (A15) (located at Ferrol). 19,500 tons.

- 41st Escort Squadron located at Rota

- 6 Frigates (Santa María class). 4,017 tons.

- 31st Escort Squadron located at Ferrol

- 5 AEGIS Frigates (Álvaro de Bazán class). 6,250 tons.

- Submarine flotilla located at Cartagena.

- 3 Submarines S-70 Galerna (Agosta class). 1,740 tons.

- 4 AIP submarines (S-80 class). (Under construction) 2,426 tons.

- MCM flotilla located at Cartagena

- 6 Minehunters M-30 (Segura class). 585 tons.

- Patrol craft flotilla

- 3 Corvettes (Descubierta class). 1,666 tons.

- 7 Patrol ships (Meteoro class) (3 ordered.) 2,500 tons.

- 4 Patrol ships (Serviola class). 1,276 tons.

- 3 Patrol ships (Chilreu class) (These vessels differ in detail). c1,500 tons.

- Various small patrol boats (being deleted as the Meteoros commission).

- Projection Group "Alfa" located at Rota

- TOTAL Tons Main Vessels: 233,596 Tons

See also

- Salve Marinera

- Coats of arms, badges and emblems of Spanish Armed Forces#Navy

- List of retired Spanish Navy ships

- List of future Spanish Navy ships

References

- ↑ es:Armada Española

- ↑ http://www.armada.mde.es/ArmadaPortal/page/Portal/ArmadaEspannola/_inicio_home/prefLang_es/

- ↑ "España Hoy 2016-2016". lamoncloa.gob.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "World Air Forces 2016". Flightglobal: p. 29. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "Royal Decree 351/2017" (PDF). Spanish Official Gazette.

- ↑ Gabriel Cardona, El Problema Militar en España, Ed. Historia 16, Madrid 1990, pg. 158-159

- ↑ Spanish Navy. "Armada Española - Ministerio de Defensa - Gobierno de España". mde.es. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ↑ Defensa Antimisil Meroka (in Spanish)

- ↑ "! Murcia Today - The Principe De Asturias Will Be Decommissioned Today". murciatoday.com. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ↑ http://www.defensa.gob.es/Galerias/presupuestos/presupuesto-defensa-2012.pdf Military Budget 2012, page 454

- ↑ es:Armada Española#La Armada hoy

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Armada Española. |

- Official website (in Spanish)

- http://www.todoababor.es (Spanish Naval History)

- History of Spanish Mariners

- http://www.revistanaval.com

- http://www.losbarcosdeeugenio.com/principal_es.html

- El Arma Submarina Española (unofficial website)

- http://www.fotosdebarcos.com (Spanish Navy Section, see Armada Española with all kind of Spanish navy ships)

- Spanish Navy page on Andrew Toppan's Haze Gray and Underway

- Spain Plans to Upgrade Navy's Projection Group

- Foro Militar General (unofficial forum)

- Warships of the Spanish Civil War

- BUQUESDEGUERRA.TK, Spanish website about warships