Space launch market competition

In the early 2010s, a new phase of space launch market competition emerged in the space launch services market.

History

In the early decades of the Space Age—1950s–2000s—the government space agencies of the Soviet Union and United States pioneered space technology augmented by collaboration with affiliated design bureaus in the USSR and contracts with commercial companies in the US. All rocket designs were built explicitly for government purposes. The European Space Agency was formed in 1975, largely following the same model of space technology development, and other national space agencies—such as China's CNSA[1] and India's ISRO[2]— also financed the indigenous development of their own national designs.

Communications satellites were the principal non-government market. Although launch competition in the early years after 2010 occurred only in and amongst global commercial launch providers, the US market for military launches began to experience multi-provider competition in 2015, as the US government moved away from their previous monopoly arrangement with United Launch Alliance for military launches.[3][4] By mid-2017, the results of this multi-year competitive pressure on launch prices was being observed in the actual numbers of launches achieved. With frequent recovery of first-stage boosters by SpaceX, "expendable missions are now a rare occurrence" for them.[5]

1970s and 1980s: Commercial satellites begin to emerge

Non-military commercial satellites began to be launched in volume in the 1970s and 1980s, but launch services were supplied exclusively with launch vehicles that had been originally developed for the various national military programs, with attendant higher cost structures.[6]

SpaceNews journalist Peter B. De Selding has asserted that French government leadership, and the Arianespace consortium "all but invented the commercial launch business in the 1980s" principally "by ignoring U.S. government assurances that the reusable U.S. space shuttle would make expendable launch vehicles like Ariane obsolete."[7]

Little market competition emerged inside any national market prior to approximately the late 2000s. Some global commercial competition arose between the national providers of various nation states for international commercial satellite launches. Within the US, as late as 2006, the high cost structures built in to government contractor's—Boeing's Delta IV and Lockheed Martin's Atlas V—launch vehicles left little commercial opportunity for US launch service providers but considerable opportunity for low-cost Russian boosters based on leftover Cold War military missile technology.[8]

DARPA's Simon P. Worden and USAF's Jess Sponable analyzed the situation in 2006 and offered that "One bright point is the emerging private sector, which [was then] pursuing suborbital or small lift capabilities." They concluded "Although such vehicles support very limited US Department of Defense or National Aeronautics and Space Administration spaceflight needs, they do offer potential technology demonstration stepping stones to more capable systems needed in the future."[8]; demonstrating capabilities that would grow in the next five years while supporting published list prices substantially below the rates on offer by the national providers.[9]

2010s: Launch market competition and pricing pressure

After approximately 2010, new private options for obtaining spaceflight services emerged, bringing substantial price pressure into the existing market.[9][10][11][12]

In early December 2013, SpaceX flew its first launch to a geosynchronous orbit providing additional credibility to its low prices which had been published since at least 2009. The low launch prices offered by SpaceX (less than $2,500 per pound to orbit for Falcon 9 v1.1 and $1,000 for Falcon Heavy),[13] especially for communication satellites flying to geostationary (GTO) orbit, resulted in market pressure on its competitors to lower their own prices.[14]

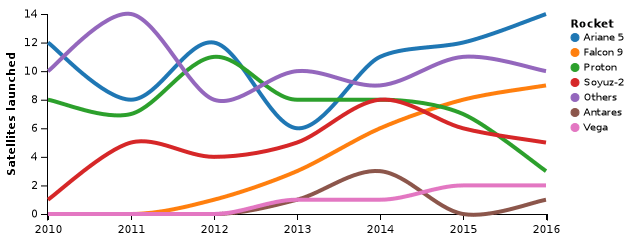

In years prior to 2013, the communications satellite launch market had been dominated by Europe's Arianespace, which flies the Ariane 5, and International Launch Services (ILS), which markets Russia's Proton vehicle.[14] In November 2013 Arianespace announced new pricing flexibility for the "lighter satellites" it carries to orbits aboard its Ariane 5 in response to SpaceX's growing presence in the worldwide launch market,[15] and followed in early 2014 with a request to European governments for additional subsidies to face the competition from SpaceX.[16]

By late 2013, with a published price of US$56.5 million per launch to low Earth orbit, "Falcon 9 rockets [were] already the cheapest in the industry. Reusable Falcon 9s could drop the price by an order of magnitude, sparking more space-based enterprise, which in turn would drop the cost of access to space still further through economies of scale."[10] Falcon 9 GTO missions 2014 pricing was approximately US$15 million less than a launch on a Chinese Long March 3B.[17] Despite SpaceX prices being somewhat lower than Long March prices, the Chinese Government and the Great Wall Industry company—which markets the Long March for commsat missions—made a policy decision to maintain commsat launch prices at approximately US$70 million.[18]

Continuing to face "stiff competition on price,"[9] seven European satellite operator companies—including the four largest in the world by annual revenue—requested in April 2014 that the ESA "find immediate ways to reduce Ariane 5 rocket launch costs and, in the longer term, make the next-generation Ariane 6 vehicle more attractive for smaller telecommunications satellites. ... [C]onsiderable efforts to restore competitiveness in price of the existing European launcher need to be undertaken if Europe is [to] maintain its market situation. In the short term, a more favorable pricing policy for the small satellites currently being targeted by SpaceX seems indispensable to keeping the Ariane launch manifest strong and well-populated."[19] In competitive bids during 2013 and early 2014, SpaceX was winning many launch customers that formerly "would have been all-but-certain clients of Europe's Arianespace launch consortium, with prices that are $60 million or less."[19]

In June 2014, Arianespace CEO Stephane Israel announced that European efforts to remain competitive in response to SpaceX' recent success have begun in earnest, including the creation of a new joint venture company from Arianespace's two largest shareholders: the launch-vehicle producer Airbus and engine-producer Safran. No specific details to become more competitive were released at the time.[20] In 2015, the European multinational space agency—the European Space Agency (ESA)—is endeavoring to reorganize in order to reduce bureaucracy and decrease inefficiencies in launcher and satellite spending which have been historically tied to the amount of tax funds that each country has provided to the ESA.[21]

In August 2014, Eutelsat, the third-largest fixed satellite services operator worldwide by revenue, indicated that it plans to spend approximately €100 million less each year in the next three years, due to lower prices for launch services and by transitioning their commsats to electric propulsion. They indicated that they are using the lower prices they can get from SpaceX against Arianespace in negotiation for launch contracts.[22] By November 2014, SpaceX had "already begun to take market share"[23] from Arianespace. Eutelsat CEO Michel de Rosen said, in reference to ESA's program to develop the Ariane 6, "Each year that passes will see SpaceX advance, gain market share and further reduce its costs through economies of scale."[23] European government research ministers approved the development of the new European rocket—Ariane 6—in December 2014, projecting the rocket would be "cheaper to construct and to operate" and that "more modern methods of production and a streamlined assembly to try to reduce unit costs" plus "the rocket's modular design can be tailored to a wide range of satellite and mission types [so it] should gain further economies from frequent use."[9] In early 2016, Arianespace was projecting a launch price of €90–100 million, about one-half of the 2015 Ariane 5 per launch price.[7]

Facing direct market competition from SpaceX, the large US launch provider United Launch Alliance (ULA) announced strategic changes in 2014 to restructure its launch business—reducing two launch vehicles to one—while implementing an iterative and incremental development program to build a partially-reusable and much lower-cost launch system over the next decade.[24] In October 2014, ULA announced a major restructuring of processes and workforce in order to decrease launch costs by half. One of the reasons given for the restructuring and new cost reduction goals was competition from SpaceX. ULA has had less "success landing contracts to launch private, commercial communications and earth observation satellites" than it has had with launch US military payloads, but CEO Tory Bruno believes the new lower-cost launcher can be competitive and succeed in the commercial satellite sector.[25] The US GAO has calculated that the average cost of each ULA rocket launch for the US government has risen to approximately US$420 million.[26] In May 2015, ULA stated that it would go out of business unless it won commercial and civil satellite launch orders to offset an expected slump in U.S. military and spy launches.[27]

As of 2015, SpaceX had remained "the low-cost supplier in the industry."[28] However, in the market for launch of US military payloads, ULA faced no competition for the launches for nearly a decade, since the formation of the ULA joint venture from Lockheed Martin and Boeing in 2006. But SpaceX is also upsetting the traditional military space launch arrangement in the US, which has been called a monopoly by space analyst Marco Caceres and criticized by some in the US Congress.[29] As of May 2015, the SpaceX Falcon 9 v1.1 was certified by the USAF to compete to launch many of the expensive satellites which are considered essential to US national security.[30]

University of Southampton researcher Clemens Rumpf argues that the global launch industry was developed in an "old world where space funding was provided by governments, resulting in a stable foundation for [global] space activities. The money for the space industry [had been] secure and did not encourage risk-taking in the development of new space technologies. ... the space landscape [had not changed much since the mid-1980s]." As a result, the emergence of SpaceX was a surprise to other launch providers "because the need to evolve launcher technology by a giant leap was not apparent to them. SpaceX shows that technology has advanced sufficiently in the last 30 years to enable new, game changing approaches to space access."[31] The Washington Post has said that the changes occasioned from multiple competing service providers has resulted in a revolution in innovation.[12]

By mid-2015, Arianespace was speaking publicly about job reductions as part of an attempt to remain competitive in the "European industry [which is being] restructured, consolidated, rationalised and streamlined" to respond to SpaceX price competition. Still, "Arianespace remained confident it could maintain its 50 per cent share of the space launch market despite SpaceX's slashing prices by building reliable rockets that are smaller and cheaper."[32]

Following the first successful landing and recovery of a SpaceX Falcon 9 first stage in December 2015, equity analysts at investment bank Jefferies estimated that launch costs to satellite operators using Falcon 9 launch vehicles may decline by about 40 percent of SpaceX' typical US$61 million per launch,[33] although SpaceX has only forecast an approximately 30 percent launch price reduction from the use of a reused first stage.[34]

In March 2017, SpaceX reflew an orbital booster stage that had been previously launched, landed and recovered, stating that the cost to the company of doing so "was substantially less than half the cost" of a new first stage. COO Gwynne Shotwell said that the cost savings "came even though SpaceX did extensive work to examine and refurbish the stage. We did way more on this one than [is planned for future recovered stages]."[35]

A 2017 industry-wide view by SpaceNews reported: By 5 July 2017, SpaceX had launched 10 payloads during a bit over 6 months—"outperform[ing] its cadence from earlier years"—and "is well on track to hit the target it set last year of 18 launches in a single year."[5] By comparison, "France-based Arianespace, SpaceX’s chief competitor for commercial telecommunications satellite launches, is launching 11 to 12 times a year using its fleet of three rockets — the heavy-lift Ariane 5, medium-lift Soyuz and light-lift Vega. ... Russia has the ability to launch a dozen or more times with Proton doing both government and commercial missions, but has operated at a slower cadence the past few years due to launch failures and this year’s discovery of an incorrect material used in some rocket engines. United Launch Alliance, SpaceX’s chief competitor for defense missions, regularly conducts around a dozen or more launches per year, but the Boeing-Lockheed Martin joint venture has only performed four missions in 2017 so far."[5]

Raising private capital

Private capital invested in the space launch industry prior to 2015 was modest. From 2000 through the end of 2015, a total of US$13.3 billion of investment finance has been invested in the space sector, with US$2.9 billion of that being venture capital financing.[36] In 2015, venture capital firms invested US$1.8 billion in private spaceflight companies, more than they had in the previous 15 years combined.[36]

For the space launch sector, this began to change with the January 2015 Google and Fidelity Investments investment of US$1 billion in SpaceX. While private satellite manufacturing companies had previously raised large capital rounds, that was the largest investment to date in a launch service provider.[37]

SpaceX is currently developing both the Falcon Heavy and the ITS launch vehicle with private capital. No government financing is being provided for the development of either rocket.[38][39]

After decades of reliance on government funding to develop the Atlas and Delta families of launch vehicles, the successor company—United Launch Alliance (ULA)—began, in October 2014, development of a rocket with private funds as one part of a solution for a problem of "skyrocketing launch costs" at ULA.[11] However, by March 2016 it had become clear that the new Vulcan launch vehicle would be developed with funding via a public–private partnership with the US government. By early 2016, the US Air Force had committed US$201 million of funding for Vulcan development. ULA has not "put a firm price tag on [the total cost of Vulcan development but ULA CEO Tory Bruno has] said new rockets typically cost $2 billion, including $1 billion for the main engine,"[40] and ULA has asked the US government to provide a minimum of US$1.2 billion by 2020 to assist it in developing the new US launch vehicle.[40] It is unclear how the change in development funding mechanisms might change ULA plans for pricing market-driven launch services. Vulcan is a large orbital launch vehicle with first flight planned no earlier than 2019.[41] Since Vulcan development began in October 2014, the privately generated funding for Vulcan development has been approved only on a short term basis.[11][40] The United Launch Alliance board of directors—composed entirely of executives from Boeing and Lockheed Martin—is approving development funding on a quarter-by-quarter basis.[42]

Other launch service providers are developing new space launch systems with substantial government capital investment. For the new European Space Agency (ESA) launch vehicle—Ariane 6, aiming for flight in the 2020s—€400 million of development capital was requested to be "industry's share", ostensibly private capital, while €2.815 billion was slated to be provided by various European government sources at the time the early finance structure was made public in April 2015.[43] In the event, France's Airbus Safran Launchers—the company building the Ariane 6—did agree to provide €400 million of development funding in June 2015, with expectation of formalizing the development contract in July 2015.[44]

As of May 2015, the Japanese legislature was considering legislation to provide a legal framework for private company spaceflight initiatives in Japan. It was not clear whether the legislation would become law and, if so, whether significant private capital would subsequently enter the Japanese space launch industry as a result.[45]In the event, the legislation appears to have not become law, and little change in the funding mechanism for Japanese space vehicles are anticipated.

2019 and beyond

United Launch Alliance (ULA) entered into a partnership with Blue Origin in September 2014 in order to develop the BE-4 LOX/methane engine to replace the RD-180 on a new lower-cost first stage booster rocket. At the time, the engine was already in its third year of development by Blue Origin, and ULA indicated that they expect the new stage and engine to start flying no earlier than 2019 on a successor to the Atlas V.[46] A month later, ULA announced a major restructuring of processes and workforce in order to decrease launch costs by half. One of the reasons given for the restructuring and new cost reduction goals was competition from SpaceX. ULA intends to have preliminary design ideas in place for a blending of the Atlas V and Delta IV technology by the end of 2014.[25][47]

Arianespace has commenced development of the Ariane 6, as its new entrant into the commercial launch market, with operational flights beginning in 2020.[48]

Blue Origin is also planning to begin flying its own orbital launch vehicle—the New Glenn—in 2020, a rocket that will also use the Blue BE-4 engine on the first stage, same as the ULA Vulcan. However, Blue does not currently plan to compete for the US military launch market, stating that the market is "a relatively small number of flights. It's very hard to do well and ULA is already great at it. I'm not sure where we would add any value."[49] Bezos sees competition as a good thing, particularly as competition leads to his ultimate goal of getting "millions and millions of people living and working in space."[49]

As of January 2015, the French space agency CNES is working with Germany and a few other governments to start a modest research effort with a hope to propose a LOX/methane reusable launch system by mid-2015, with flight testing unlikely before approximately 2026. The design objective is to reduce both the cost and duration of reusable vehicle refurbishment, and is partially motivated by the pressure of lower-cost competitive options with newer technological capabilities not found in the Ariane 6.[50][51]

SpaceX has publicly indicated that if they are successful with developing the reusable technology, launch prices in the US$5 to 7 million range for the reusable Falcon 9 are possible in the longer term.[52]

Competition for the American heavy-lift market

As early as August 2014, media sources noted that the US launch market may have two competitive super-heavy launch vehicles available in the 2020s to launch payloads of 100 metric tons (220,000 lb) or more to low-Earth orbit. The US government is currently developing the Space Launch System (SLS), a heavy-lift launch vehicle for lifting very large payloads of 70 to 130 tonnes (150,000 to 290,000 lb) from Earth. On the commercial side, SpaceX is privately developing the Interplanetary Transport System, which is being designed to lift a 300 tonnes (660,000 lb) payload to Earth orbit in reusable mode, or 550 tonnes (1,210,000 lb) in expendable mode. SpaceX has played down the competitive aspect with SLS. However, if SpaceX makes progress on its super-heavy launch vehicle in "the coming years, it is almost unavoidable that America's two HLVs will attract comparisons and a healthy debate, potentially at the political level."[53]

Launch contract competitive results

Before 2014

Arianespace has dominated the commercial launch market for many years. "In 2004, for example, they held over 50% of the world market."[54]

- 2010: 26 geostationary commercial satellites were ordered under long-term launch contracts.[55]

- 2011: Only 17 geostationary commercial satellites went under contract during 2011 as an "historically large capital spending surge by the biggest satellite fleet operators" began to tail off, something that had been anticipated to follow the various satellite fleets being substantially upgraded.[55]

- 2012: As of September 2012, the major launch providers globally were Arianespace (France), International Launch Services (United States) which markets the Russian Proton launch vehicle, and Sea Launch of Switzerland which markets the Russian-Ukrainian Zenit rocket. In late 2012, each of them had manifests that were "full or nearly so for both 2012 and 2013."[55]

- 23 geostationary orbit communications satellites were placed under firm contract during 2013.[56]

2014

A total of 20 launches were booked in 2014 for commercial launch service providers. 19 were for flights to geostationary orbit (GEO), one was for a low-Earth orbit (LEO) launch.[57]

Arianespace and SpaceX each signed nine contracts for geostationary launches, while Mitsubishi Heavy Industries was awarded one. United Launch Alliance signed one commercial contract to launch an Orbital Sciences Corporation Cygnus spacecraft to the LEO-orbiting International Space Station following the destruction over the pad of an Orbital Antares vehicle in October 2014. This was the first year in some time that no commercial launches were booked on the Russian (Proton-M) and Russian-Ukrainian (Zenit) launch service providers.[57]

For perspective, eight additional satellites in 2014 were booked "by national launch providers in deals for which no competitive bids were sought."[57]

Overall in 2014 Arianespace took 60% of commercial launch market share.[58][59]

2015

Overall in 2015, Arianespace signed 14 commercial-order launch contracts for geosynchronous-orbit commsats, while SpaceX received only 9, with International Launch Services (Proton) and United Launch Alliance signing one contract each. In addition, Arianespace signed their largest launch contract ever—for 21 LEO launches for OneWeb using the Europeanized Russian Soyuz launch vehicle launching from the ESA spaceport—and two Vega smallsat launches.[7]

In a 2015 US competition for a (no earlier than 2017[60] but possibly planned for 2018 as of November it costs 11 million US dollars 2015[61]) US military launch to loft the first of the third-generation GPS III satellites into orbit, ULA—after having held a government-sanctioned monopoly on US military launches for the previous decade—declined to even submit a bid, thereby leaving the likely contract award winner to be SpaceX, the only other domestic US-provider of launch services to be certified as usable by the US military.[3]

Launch industry response

In addition to price reductions for proffered launch service contracts, launch service providers are restructuring to meet increased competitive pressures within the industry.

ULA has begun a major restructuring of processes and workforce in order to decrease launch costs by half.[25] In May 2015, ULA announced it would decrease its executive ranks by 30 percent in December 2015, with the layoff of 12 executives. The management layoffs are the "beginning of a major reorganization and redesign" as ULA endeavours to "slash costs and hunt out new customers to ensure continued growth despite the rise of [SpaceX]".[62]

According to one Arianespace managing director, "'It's quite clear there's a very significant challenge coming from SpaceX,' he said. 'Therefore, things have to change … and the whole European industry is being restructured, consolidated, rationalised and streamlined.' "[63]

Jean Botti, Chief technology officer for Airbus (which makes the Ariane 5) warned that "those who don't take Elon Musk seriously will have a lot to worry about"[64]

Airbus announced in 2015 that they would open a R&D center and venture capital fund in Silicon Valley.[65] Airbus CEO Fabrice Bregier stated: "What is the weakness of a big group like Airbus when we talk about innovation? We believe that we have better ideas than the rest of the world. We believe that we know because we control the technologies and platforms. The world has shown us in the car industry, the space industry and the hi-tech industry that this is not true. And we need to be open to others' ideas and others' innovations,"[66]

Airbus Group CEO Tom Enders stated that "The only way to do it for big companies is really to create spaces outside of the main business where we allow and where we incentivize experimentation...That is what we have started to do but there is no manual...It is a little bit of trial and error. We all feel challenged by what the Internet companies are doing."[67]

Following a SpaceX launch vehicle failure in June 2015—due to the lower prices, increased flexibility for partial-payload launches of the Ariane heavy lifter, and decreased cost of operations of the ESA Guiana Space Center spaceport—Arianespace regained the competitive lead in commercial launch contracts signed in 2015. SpaceX successful recovery of a first stage rocket in December 2015 has not changed the Arianespace outlook. Arianespace CEO Israel stated that the "challenges of reusability ... have not disappeared. ... The stress on stage or engine structures of high-speed passage through the atmosphere, the performance penalty of reserving fuel for the return flight instead of maximizing rocket lift capacity, the need for many annual launches to make the economics work – all remain issues."[7]

Effect on related industries

Satellite design and manufacturing is beginning to take advantage of these lower-cost options for space launch services.

One such satellite system is the Boeing 702SP which can be launched as a pair on a lighter-weight dual-commsat stack—two satellites conjoined on a single launch—and which was specifically designed to take advantage of the lower-cost SpaceX Falcon 9 launch vehicle.[68][69] The design was announced in 2012 and the first two commsats of this design were lofted in a paired launch in March 2015, for a record low launch price of approximately US$30 million per GSO commsat.[70] Boeing CEO James McNerney has indicated that SpaceX's growing presence in the space industry is forcing Boeing "to be more competitive in some segments of the market."[71]

Early information on a new constellation of 4000 satellites intended to provide global internet services, along with a new factory dedicated to manufacturing low-cost smallsat satellites, indicate that the satellite manufacturing industry may "experience a shock similar to what the launcher industry is experiencing" in the 2010s.[31]

Venture capital investor Steve Jurvetson has indicated that it is not merely the lower launch prices, but the fact that the known prices act as a signal in conveying information to other entrepreneurs who then use that information to bring on new related ventures.[72]

References

- ↑ Sheehan, Michael (22 Dec 2010). "Rising Powers : Competition and Cooperation in the new Asian 'Space Race'". RUSI Journal: 44–50. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

Asia's rising powers are developing indigenous space programmes at a startling pace. Though some hedging behaviour is apparent, most are designed to bolster technological autonomy and augment national prestige. Nevertheless, China and India are both pursuing anti-satellite capabilities. Not yet a full-blown race, both competition and cooperation is possible between Asia's giants.

- ↑ Nagappa, Rajaram (2 Dec 2016). "Development of Space Launch Vehicles in India". Astropolitics : The International Journal of Space Politics & Policy: 158–176. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

The Indian space program is a spacefaring success story with demonstrated capability in the design and building of application and scientific satellites, and the means to launch them into desired orbits. The end-to-end mission planning and execution capability comes with a high emphasis on self-reliance. Sounding rockets and small satellite launch vehicles provided the initial experience base for India. This experience was consolidated and applied to realize larger satellite launch vehicles. While many of the launch vehicle technologies were indigenously developed, the foreign acquisition of liquid propulsion technologies did help in catalyzing the development efforts. In this case, launch vehicle concept studies showed the inevitability of using a cryogenic upper stage for geosynchronous Earth orbit missions, which proved to be difficult technically and encountered substantial delays, given the geopolitical situation. However, launch capability matured from development to operational phases, and today, India’s Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle and Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle are in a position to meet both domestic and international market demands.

- 1 2 Davenport, Christian (2015-11-16). "ULA bows out of Pentagon launch competition, paving way for SpaceX". Washington Post. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

Faced with competition for the first time, the United Launch Alliance said Monday that it would not bid on the next contract to send Pentagon satellites into space, a stunning announcement for a company that held a monopoly on national security launches for a decade.

- ↑ de Selding, Peter B. (2016-03-16). "ULA intends to lower its costs, and raise its cool, to compete with SpaceX". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

A de facto monopoly was born with U.S. government blessing and with a series of lucrative U.S. government contracts whose principal goal was reliability and capability, not value for money.

- 1 2 3 http://spacenews.com/spacex-crests-double-digit-marker-notches-tenth-launch-in-a-single-year-for-first-time/

- ↑ Stromberg, Joseph (2015-09-04). "How did private companies get involved in space?". Vox. Retrieved 2015-10-14.

the first object in space built entirely by a private company was Telstar 1, a communications satellite launched into orbit by a NASA rocket in 1962. Telstar was followed by hundreds of other private satellites involved in communication and other fields. For decades, US government policy dictated that only NASA was allowed to put these satellites into space, but in 1984, as part of a broader move toward deregulation, Congress passed a law allowing private companies to conduct their own launch their own payloads [and further broadened that legal regime in 1990.]

- 1 2 3 4 "Arianespace Surpassed SpaceX in Commercial Launch Orders in 2015". Space News. 6 January 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- 1 2 Worden, Simon P.; Sponable, Jess (22 Sep 2006). "Access to Space: A Strategy for the Twenty-First Century". Astropolitics : The International Journal of Space Politics & Policy. 4 (1): 69–83.

The United States (US) launch infrastructure is at a crisis point. Human access to space embodied in the Space Shuttle is due to be phased out by 2010. Currently, there are no heavy lift, 100 ton class launchers to support the US national vision for space exploration. Medium and large expendable launch providers, Boeing's Delta IV, and Lockheed-Martin's Atlas V Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicles are so expensive that the Delta no longer carries commercial payloads and the Atlas is unlikely to show significant growth without equally significant cost reductions and commercial traffic growth. This set of circumstances questions US dependence on these launch vehicles for national security purposes. High cost growth also exists with small launch vehicles, such as Pegasus, and the promising new field of small and microsatellites is little developed in the US, while foreign efforts, particularly European, are expanding largely on the availability of low-cost Russian boosters. One bright point is the emerging private sector, which is initially pursuing suborbital or small lift capabilities. Although such vehicles support very limited US Department of Defense or National Aeronautics and Space Administration spaceflight needs, they do offer potential technology demonstration stepping stones to more capable systems needed in the future of both agencies. This article outlines the issues and potential options for the US Government to address these serious shortcomings.

- 1 2 3 4 "Europe to press ahead with Ariane 6 rocket". BBC News. Retrieved 2015-06-25.

- 1 2 Belfiore, Michael (2013-12-09). "The Rocketeer". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- 1 2 3 Pasztor, Andy (2015-09-17). "U.S. Rocket Supplier Looks to Break 'Short Leash'". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2015-10-14.

The aerospace giants [Boeing Co. and Lockheed Martin Corp.] shared almost $500 million in equity profits from the rocket-making venture last year, when it still had a monopoly on the business of blasting the Pentagon's most important satellites into orbit. But since then, 'they've had us on a very short leash,' Tory Bruno, United Launch's chief executive, said.

- 1 2 Davenport, Christian (2016-08-19). "The inside story of how billionaires are racing to take you to outer space". Washington Post. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

the government’s monopoly on space travel is over

- ↑ Andrew Chaikin. "Is SpaceX Changing the Rocket Equation?". Air & Space Magazine. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- 1 2 Amos, Jonathan (2013-12-03). "SpaceX launches SES commercial TV satellite for Asia". BBC News. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

The commercial market for launching telecoms spacecraft is tightly contested, but has become dominated by just a few companies - notably, Europe's Arianespace, which flies the Ariane 5, and International Launch Services (ILS), which markets Russia's Proton vehicle. SpaceX is promising to substantially undercut the existing players on price, and SES, the world's second-largest telecoms satellite operator, believes the incumbents had better take note of the California company's capability. 'The entry of SpaceX into the commercial market is a game-changer'

- ↑ de Selding, Peter B. (2013-11-25). "SpaceX Challenge Has Arianespace Rethinking Pricing Policies". Space News. Retrieved 2013-11-27.

The Arianespace commercial launch consortium is telling its customers it is open to reducing the cost of flights for lighter satellites on the Ariane 5 rocket in response to the challenge posed by SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket.

- ↑ Svitak, Amy (2014-02-11). "Arianespace To ESA: We Need Help". Aviation Week. Retrieved 2014-02-12.

- ↑ Svitak, Amy (2014-03-10). "SpaceX Says Falcon 9 To Compete For EELV This Year". Aviation Week. Retrieved 2014-03-11.

Advertised at $56.5 million per launch, Falcon 9 missions to GTO cost almost $15 million less than a ride atop a Chinese Long March 3B

- ↑ Messier, Doug (2013-09-28). "China to Hold Long March Pricing Steady". Parabolic Arc. Retrieved 2014-12-14.

- 1 2 de Selding, Peter B. (2014-04-14). "Satellite Operators Press ESA for Reduction in Ariane Launch Costs". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- ↑ Abbugao, Martin (2014-06-18). "European satellite chief says industry faces challenges". Phys.org. Retrieved 2014-06-19.

- ↑ de Selding, Peter B. (2015-07-29). "Tough Sledding for Proposed ESA Reorganization". Space News. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ↑ de Selding, Peter B. (2014-07-31). "Eutelsat Orders All-electric Satellite; Pledges to Limit Capital Spending". Space News. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- 1 2 de Selding, Peter B. (2014-11-20). "Europe's Satellite Operators Urge Swift Development of Ariane 6". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2014-11-21.

- ↑ Gruss, Mike (2015-04-24). "Evolution of a Plan : ULA Execs Spell Out Logic Behind Vulcan Design Choices". Space News. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 Avery, Greg (2014-10-16). "ULA plans new rocket, restructuring to cut launch costs in half". Denver Business Journal. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- ↑ Petersen, Melody (2014-12-12). "Congress OKs bill banning purchases of Russian-made rocket engines". LA Times. Retrieved 2014-12-14.

Costs of launching military satellites has skyrocketed under contracts the Air Force has given to United Launch Alliance. The average cost for each launch using rockets from Boeing and Lockheed has soared to $420 million, according to an analysis by the Government Accountability Office.

- ↑ "Lockheed-Boeing rocket venture needs commercial orders to survive". Yahoo News. 21 May 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ↑ Vance, Ashlee (2015). Elon Musk : Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future. New York: HarperCollins. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-06-230123-9.

- ↑ Petersen, Melody (2014-11-28). "SpaceX may upset firm's monopoly in launching Air Force satellites". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2014-11-25.

- ↑ "Air Force's Space and Missile Systems Center Certifies SpaceX for National Security Space Missions". af.mil. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- 1 2 Rumpf, Clemens (2 February 2015). "Increased competition will challenge ESA's space authority". The Space Review. SpaceNews. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ↑ "NBN launcher Arianespace to cut jobs and costs to fight SpaceX". Bain Daily. Sydney Morning Herald. 2015-05-19. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ↑ Forrester, Chris (2016-01-20). "Launch discounts likely from SpaceX". Advanced Television. Retrieved 2016-01-25.

- ↑ de Selding, Peter B. (2016-03-10). "SpaceX says reusable stage could cut prices 30 percent, plans November Falcon Heavy debut". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2016-03-11.

- ↑ http://spacenews.com/spacex-gaining-substantial-cost-savings-from-reused-falcon-9/

- 1 2 "VCs Invested More in Space Startups Last Year Than in the Previous 15 Years Combined". Fortune. 2016-02-22. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

The Tauri Group suggests that space startups turned a major corner in 2015, at least in the eyes of venture capital firms that are now piling money into young space companies with unprecedented gusto. ... he study also found that more than 50 venture capital firms invested in space companies in 2015, signaling that venture capital has warmed to a space industry it has long considered both too risky and too slow to yield returns.

- ↑ Hull, Dana; Johnsson, Julie (2015-02-06). "Space race 2.0 sucks in $US10b from private companies". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ↑ Boozer, R.D. (2014-03-10). "Rocket reusability: a driver of economic growth". The Space Review. 2014. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- ↑ Belluscio, Alejandro G. (2014-03-07). "SpaceX advances drive for Mars rocket via Raptor power". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- 1 2 3 Gruss, Mike (2016-03-10). "ULA's parent companies still support Vulcan … with caution". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2016-03-11.

- ↑ Gruss, Mike (2015-04-13). "ULA's Vulcan Rocket To be Rolled out in Stages". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2015-06-06.

- ↑ Avery, Greg (2015-04-16). "The fate of United Launch Alliance and its Vulcan rocket may lie with Congress" (Denver Business Journal). Retrieved 2015-06-06.

- ↑ de Selding, Peter B. (3 April 2015). "Desire for Competitive Ariane 6 Nudges ESA Toward Compromise in Funding Dispute with Contractor". Space News. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ de Selding, Peter B. (2015-05-29). "Airbus Safran Agrees to $440 Million Ariane 6 Contribution". Space News. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ "Private-sector rocket launch legislation eyed". Japan News. Yomiuri Shimbun. 2015-06-03. Retrieved 2015-06-06.

- ↑ Ferster, Warren (2014-09-17). "ULA To Invest in Blue Origin Engine as RD-180 Replacement". Space News. Retrieved 2014-12-13.

- ↑ Delgado, Laura M. (2014-11-14). "ULA's Tory Bruno Vows To Transform Company". SpacePolicyOnline.com. Retrieved 2014-12-13.

- ↑ Peter B. De Selding (2014-12-02). "ESA Members Agree To Build Ariane 6, Fund Station Through 2017". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2014-12-13.

- 1 2 Price, Wayne T. (2016-03-12). "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin could change the face of space travel". Florida Today. Retrieved 2016-03-13.

- ↑ de Selding, Peter B. (5 January 2015). "CNES proposal". de Selding is a journalist for Space News. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ↑ de Selding, Peter B. (5 January 2015). "With Eye on SpaceX, CNES Begins Work on Reusable Rocket Stage". SpaceNews. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ↑ Messier, Doug (January 14, 2014). "Shotwell: Reusable Falcon 9 Would Cost $5 to $7 Million Per Launch". Parabolic Arc. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (2014-08-29). "Battle of the Heavyweight Rockets -- SLS could face Exploration Class rival". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved 2015-03-23.

- ↑ Orwig, Jessica (2015-04-17). "SpaceX's biggest competitor is a company you've never heard of". Business Insider. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 de Selding, Peter B. (10 September 2012). "Satellite Orders Drop but Near-term Launch Manifests Are Full". Space News. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ↑ de Selding, Peter B. (13 January 2014). "Launch & Satellite Contract Review: High-throughput Helps Boost Satellite Orders". Space News. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 de Selding, Peter B. (12 January 2015). "Arianespace, SpaceX Battled to a Draw for 2014 Launch Contracts". SpaceNews. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ↑ "World Satellite Business Week 2014: A rich harvest of contracts for Arianespace" (Press release). 8 September 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ↑ "Europe's Arianespace Claims 60% Of The Commercial Launch Market". 9 September 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ↑ Mike Gruss. "Launch of First GPS 3 Satellite Now Not Expected Until 2017". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- ↑ https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-11-17/musk-s-spacex-may-win-first-u-s-defense-launch-as-rival-exits

- ↑ Shalal, Andrea (2015-05-15). "Lockheed-Boeing venture lays off 12 executives in major reorganization". Reuters. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ↑ "NBN launcher Arianespace to cut jobs and costs to fight SpaceX". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ↑ "Airbus dans la Silicon Valley : une occasion manquée pour l'Europe". lesechos.fr. 3 June 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ↑ "Airbus Group starts $150 mln venture fund, Silicon Valley base". Reuters. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ↑ "In a first, Bengaluru startups on Airbus radar for mentoring business ideas under BizLabs". The Economic Times. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ↑ http://www.star-telegram.com/news/business/aviation/sky-talk-blog/article25185454.html

- ↑ Svitak, Amy (2014-03-10). "SpaceX Says Falcon 9 To Compete For EELV This Year". Aviation Week. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

But the Falcon 9 is not just changing the way launch-vehicle providers do business; its reach has gone further, prompting satellite makers and commercial fleet operators to retool business plans in response to the low-cost rocket. In March 2012, Boeing announced the start of a new line of all-electric telecommunications spacecraft, the 702SP, which are designed to launch in pairs on a Falcon 9 v1.1. Anchor customers Asia Broadcast Satellite (ABS) of Hong Kong and Mexico's SatMex plan to loft the first two of four such spacecraft on a Falcon 9.... Using electric rather than chemical propulsion will mean the satellites take months, rather than weeks, to reach their final orbital destination. But because all-electric spacecraft are about 40% lighter than their conventional counterparts, the cost to launch them is considerably less than that for a chemically propelled satellite.

- ↑ "Boeing Stacks Two Satellites to Launch as a Pair" (Press Release). Boeing. 2014-11-12. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- ↑ Graham, William (1 March 2015). "SpaceX Falcon 9 launches debut dual satellite mission". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (30 January 2015). "Boeing Head: SpaceX Making Company a Better Competitor". Space News. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ Schubarth, Cromwell (2015-06-22). "DFJ's Steve Jurvetson on why he invested in SpaceX, Planet Labs". Silicon Valley Business Journal. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

But starting from SpaceX onward, it all became very different. What really changed, I think, is the cost of access. Prior to SpaceX, not only were launch vehicles expensive, but none of the prices were really known. So if you were an entrepreneur trying to focus, like Planet Labs or Spire, it was pretty daunting. There was no rule of thumb as to what it would cost you and what kind of schedule reliability you could expect.

External links

- United Launch Alliance faces increased competition on space launches, Denver Post, 7 June 2015.

- Airbus unveils 'Adeline' re-usable rocket concept, BBC News, 5 June 2015.