Falcon Heavy

Artist's representation of Falcon Heavy Reusable on launch pad | |

| Function | Orbital super heavy-lift launch vehicle |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | SpaceX |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Cost per launch | $90M for up to 26,700 kg to GTO[1] |

| Size | |

| Height | 70 m (230 ft)[2] |

| Diameter | 3.66 m (12.0 ft)[2] |

| Width | 12.2 m (40 ft)[2] |

| Mass | 1,420,788 kg (3,132,301 lb)[2] |

| Stages | 2+ |

| Capacity | |

| Payload to LEO (28.5°) | 63,800 kg (140,700 lb)[2] |

| Payload to GTO (27°) | 26,700 kg (58,900 lb)[2] |

| Payload to Mars | 16,800 kg (37,000 lb)[2] |

| Payload to Pluto | 3,500 kg (7,700 lb)[2] |

| Associated rockets | |

| Family | Falcon 9 |

| Comparable | |

| Launch history | |

| Status | In development |

| Launch sites | |

| Total launches | 0 |

| Successes | 0 |

| Failures | 0 |

| First flight | November 2017 (planned)[3] |

| Boosters | |

| No. boosters | 2 |

| Engines | 9 Merlin 1D |

| Thrust |

Sea level: 7,607 kN (1,710,000 lbf) Vacuum: 8,227 kN (1,850,000 lbf) |

| Specific impulse |

Sea level: 282 seconds[4] Vacuum: 311 seconds[5] |

| Burn time | 162 seconds[6] |

| Fuel | Subcooled LOX / Chilled RP-1[7] |

| First stage | |

| Engines | 27 Merlin 1D (center core + two side boosters) |

| Thrust |

Sea level: 22,819 kN (5,130,000 lbf) Vacuum: 24,681 kN (5,549,000 lbf)[2] |

| Specific impulse |

Sea level: 282 seconds Vacuum: 311 seconds |

| Burn time | 162 seconds |

| Fuel | Subcooled LOX / Chilled RP-1 |

| Second stage | |

| Engines | 1 Merlin 1D Vacuum |

| Thrust | 934 kN (210,000 lbf)[2] |

| Specific impulse | 348 seconds[6] |

| Burn time | 397 seconds[2] |

| Fuel | LOX / RP-1 |

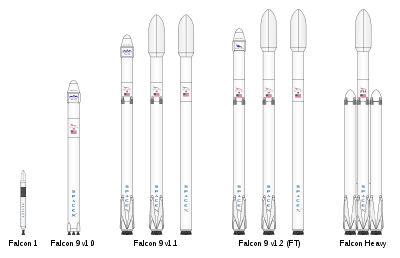

Falcon Heavy, previously known as the Falcon 9 Heavy, is a reusable super heavy lift space launch vehicle being designed and manufactured by SpaceX. The Falcon Heavy is a variant of the Falcon 9 launch vehicle and will consist of a strengthened Falcon 9 rocket core, with two additional Falcon 9 first stages as strap-on boosters.[8] This will increase the low Earth orbit (LEO) maximum payload to 63.8 metric tonnes, compared to 22.8 tonnes for a Falcon 9 full thrust. Falcon Heavy was designed from the outset to carry humans into space, and would enable crewed missions to the Moon or Mars.

The date of the maiden launch of the Falcon Heavy has been repeatedly pushed back over time, primarily due to continued maturation of the parent Falcon 9 design and a need for SpaceX to clear their existing launch manifest. The first Falcon Heavy is currently tentatively scheduled for launch in November 2017,[3] contingent upon the repair of Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Space Launch Complex 40.[9]

Development history

Conception and funding

Elon Musk first mentioned Falcon Heavy in a September 2005 news update, referring to a customer request from 18 months prior.[10] Various solutions using the planned Falcon 5 had been explored, but the only cost effective, reliable iteration was one that used a 9-engine first stage - the Falcon 9. Further exploration of the capabilities of the notional Falcon 9 vehicle led to a Falcon 9 Heavy concept: "two first stages as liquid strap on boosters, like Delta IV Heavy, allowed us to place about 25 tons into LEO – more than any launch vehicle in use today."

Development

As the Falcon Heavy was based on common fuselage and engines, subsequent development followed that of the Falcon 9.

By 2008, SpaceX were aiming for the first launch of Falcon 9 in 2009, and "Falcon 9 Heavy would be in a couple of years." Speaking at the 2008 Mars Society Conference, Elon Musk also said that a hydrogen-fuelled upper stage would follow 2–3 years later (notionally 2013).[11] The Falcon Heavy is being developed with private capital. No government financing is being provided for its development.[12]

By April 2011, the capabilities of the Falcon 9 vehicle and performance were better understood, SpaceX having completed 2 successful demonstration missions to LEO, one of which included reignition of the second-stage engine. At a press conference at the National Press Club in Washington, DC. on 5 April 2011, Elon Musk stated that Falcon Heavy would "carry more payload to orbit or escape velocity than any vehicle in history, apart from the Saturn V Moon rocket […] and Soviet Energia rocket.”[13] In 2015, SpaceX announced a number of changes to the Falcon Heavy rocket, worked in parallel to the upgrade of the Falcon 9 v1.1 launch vehicle.[14]

Production

In 2011, with the expected increase in demand for both variants, SpaceX were planning to expand their factory, "as we build towards the capability of producing a Falcon 9 first stage or Falcon Heavy side booster every week and an upper stage every two weeks."[13] In December 2016, SpaceX released a photo showing the Falcon Heavy interstage at the company headquarter in Hawthorne, California.[15]

Testing

As of May 2013, a new, partially underground test stand was being built at the SpaceX Rocket Development and Test Facility in McGregor, Texas specifically to test the triple cores and twenty-seven rocket engines of the Falcon Heavy.[16] In May 2017, SpaceX released a video of the first static fire test of a Falcon Heavy centre core at the McGregor facility.[17][18]

Maiden flight

In April 2011, Elon Musk was targeting a first launch of Falcon Heavy from Vandenberg Air Force Base on the West Coast in 2013.[13][19] SpaceX refurbished Launch Complex 4E at Vandenberg AFB to accommodate Falcon 9 and Heavy. The first launch from the Cape Canaveral East Coast launch complex was planned for late 2013 or 2014.[20]

By September 2015, impacted by the failure of SpaceX CRS-7 that June, SpaceX rescheduled the maiden Falcon Heavy flight for April/May 2016,[21] but by February 2016 had moved that back again to late 2016. The flight was now to be launched from the refurbished Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39A.[22][23] In August 2016, the demonstration flight was moved to early 2017,[24] then to Summer 2017,[25] and finally to November 2017.[3] Further missions were rescheduled accordingly.

A second demonstration flight is currently scheduled for 2018 with the STP-2 US Air Force payload.[26] Operational GTO missions for Intelsat and Inmarsat, which were planned for late 2017, were moved to the Falcon 9 Full Thrust rocket version as it became powerful enough to lift those heavy payloads in its expendable configuration.[27][28] The first commercial GTO mission is also scheduled in 2018 for Arabsat.[29]

At a July 2017 meeting of the International Space Station Research and Development meeting in Washington, DC, Musk downplayed expectations for the success of the maiden flight saying "there's a real good chance the vehicle won't make it to orbit" and "I hope it makes it far enough away from the pad that it does not cause pad damage. I would consider even that a win, to be honest"[30]. Musk went on to say the integration and structural challenges of combining 3 Falcon 9 cores were much more difficult than expected.[31]

Design

The Heavy configuration consists of a structurally-strengthened Falcon 9 with two additional Falcon 9 first stages acting as liquid strap-on boosters,[8] which is conceptually similar to EELV Delta IV Heavy launcher and proposals for the Atlas V Heavy and Russian Angara A5V. Falcon Heavy will be more capable than any other operational rocket, with a payload of 64,000 kilograms (141,000 lb) to low earth orbit and 16,800 kilograms (37,000 lb) to trans-Mars injection.[1] The rocket was designed to meet or exceed all current requirements of human rating. The structural safety margins are 40% above flight loads, higher than the 25% margins of other rockets.[32] Falcon Heavy was designed from the outset to carry humans into space and it would restore the possibility of flying crewed missions to the Moon or Mars.[33]

The first stage is powered by three Falcon 9 derived cores, each equipped with nine Merlin 1D engines. The Falcon Heavy has a total sea-level thrust at liftoff of 22,819 kN (5,130,000 lbf), from the 27 Merlin 1D engines, while thrust rises to 24,681 kN (5,549,000 lbf) as the craft climbs out of the atmosphere.[2] The upper stage is powered by a single Merlin 1D engine modified for vacuum operation, with a thrust of 934 kN (210,000 lbf), an expansion ratio of 117:1 and a nominal burn time of 397 seconds. For added reliability of restart, the engine has dual redundant pyrophoric igniters (TEA-TEB).[8] The interstage, which connects the upper and lower stage for Falcon 9, is a carbon fiber aluminum core composite structure. Stage separation occurs via reusable separation collets and a pneumatic pusher system. The Falcon 9 tank walls and domes are made from aluminium-lithium alloy. SpaceX uses an all-friction stir welded tank. The second stage tank of Falcon 9 is simply a shorter version of the first stage tank and uses most of the same tooling, material and manufacturing techniques. This approach reduces manufacturing costs during vehicle production.[8]

All three cores of the Falcon Heavy arrange the engines in a structural form SpaceX calls Octaweb, aimed at streamlining the manufacturing process,[34] and each core will include four extensible landing legs.[35] To control the descent of the boosters and center core through the atmosphere, SpaceX uses small grid fins which deploy from the vehicle after separation.[36] After the side boosters separate, the center engine in each will burn for a few seconds in order to control the booster’s trajectory safely away from the rocket.[35][37] The legs will then deploy as the boosters turn back to Earth, landing each softly on the ground. The center core will continue to fire until stage separation, after which its legs will deploy and land it back on Earth as well. The landing legs are made of state-of-the-art carbon fiber with aluminum honeycomb. The four legs stow along the sides of each core during liftoff and later extend outward and down for landing. Both the grid fins and the landing legs on the Falcon Heavy are currently undergoing testing on the Falcon 9 launch vehicle, which are intended to be used for vertical landing once the post-mission technology development effort is completed.[38]

Capabilities

The Falcon Heavy falls into the "super heavy-lift" range of launch systems under the classification system used by a NASA human spaceflight review panel.[39]

The initial concept (Falcon 9-S9 2005) envisioned payloads of 24,750 kg to LEO, but by April 2011 this was projected to be up to 53,000 kilograms (117,000 lb)[40] with GTO payloads up to 12,000 kilograms (26,000 lb),.[41] Later reports in 2011 projected higher payloads beyond LEO, including 19,000 kilograms (42,000 lb) to geostationary transfer orbit,[42] 16,000 kilograms (35,000 lb) to translunar trajectory, and 14,000 kilograms (31,000 lb) on a trans-Martian orbit to Mars.[43][44]

By late 2013, SpaceX raised the projected GTO payload for Falcon Heavy to up to 21,200 kilograms (46,700 lb).[45]

In April 2017, the projected LEO payload for Falcon Heavy was raised from 54,400 kilograms (119,900 lb) to 63,800 kilograms (140,700 lb). The maximum payload is achieved when the rocket flies a fully expendable launch profile, not recovering any of the three first-stage boosters.[46]

| Payload history | Falcon Heavy | Falcon 9 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aug 2013 to Apr 2016 |

May 2016 to Mar 2017 |

Since Apr 2017 | ||

| LEO (28,5°) | 53,000 kg | 54,400 kg | 63,800 kg | 22,800 kg |

| GTO (27°) | 21,200 kg | 22,200 kg | 26,700 kg | 8,300 kg |

| GTO (27°) Reusable | 6,400 kg | 6,400 kg | 8,000 kg | 5,500 kg |

| Mars | 13,200 kg | 13,600 kg | 16,800 kg | 4,020 kg |

| Pluto | - | 2,900 kg | 3,500 kg | - |

Propellant crossfeed

Falcon Heavy was originally designed with a unique propellant crossfeed capability, where the center core engines are supplied with fuel and oxidizer from the two side cores, up until the side cores are near empty and ready for the first separation event.[47] Igniting all engines from all three cores at launch and operating them at full thrust with fuel mainly from the side boosters would deplete the side boosters sooner allowing for their earlier separation, in turn leaving the central core with most of its propellant at booster separation.[48] The propellant crossfeed system, nicknamed "asparagus staging", comes from a proposed booster design in a book on orbital mechanics by Tom Logsdon. According to the book, an engineer named Ed Keith coined the term "asparagus-stalk booster" for launch vehicles using propellant crossfeed.[49] Elon Musk has stated that crossfeed is not currently planned to be implemented, at least in the first Falcon Heavy version.[50]

Reusability

Although not a part of the initial Falcon Heavy design, SpaceX is doing parallel development on a reusable rocket launching system that is intended to be extensible to the Falcon Heavy, recovering all parts of the rocket.

Early on, SpaceX had expressed hopes that all rocket stages would eventually be reusable.[51] SpaceX has since demonstrated both land and sea recovery of the first stage of the Falcon 9 a number of times, and starting with payload fairing recovery.[52] This approach is particularly well suited to the Falcon Heavy where the two outer cores separate from the rocket much earlier in the flight profile, and are therefore both moving at a slower velocity at the initial separation event.[38] Since late 2013, every Falcon 9 first stage has been instrumented and equipped as a controlled descent test vehicle. For the first flight of Falcon Heavy, SpaceX aim to try recovering also the second stage.[53]

SpaceX has indicated that the Falcon Heavy payload performance to geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO) will be reduced due to the addition of the reusable technology, but would fly at much lower launch price. With full reusability on all three booster cores, GTO payload will be 8,000 kg (18,000 lb). If only the two outside cores fly as reusable cores while the center core is expendable, GTO payload would be approximately 16,000 kg (35,000 lb).[54] "Falcon 9 will do satellites up to roughly 3.5 tonnes, with full reusability of the boost stage, and Falcon Heavy will do satellites up to 7 tonnes with full reusability of the all three boost stages," [Musk] said, referring to the three Falcon 9 booster cores that will comprise the Falcon Heavy's first stage. He also said Falcon Heavy could double its payload performance to GTO "if, for example, we went expendable on the center core."

Launch prices

At an appearance in May 2004 before the United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, Elon Musk testified, "Long term plans call for development of a heavy lift product and even a super-heavy, if there is customer demand. We expect that each size increase would result in a meaningful decrease in cost per pound to orbit. ... Ultimately, I believe $500 per pound or less is very achievable."[55] This $500 per pound ($1,100/kg) goal stated by Musk in 2011 is 35% of the cost of the lowest-cost-per-pound LEO-capable launch system in a circa-2000 study: the Zenit, a medium-lift launch vehicle that can carry 14,000 kilograms (30,000 lb) into LEO.[56]

As of March 2013, Falcon Heavy launch prices are below $1,000 per pound ($2,200/kg) to low-Earth orbit when the launch vehicle is transporting its maximum delivered cargo weight.[57] The published prices for Falcon Heavy launches have moved some from year to year, with announced prices for the various versions of Falcon Heavy priced at $80–125 million in 2011,[40] $83–128M in 2012,[41] $77–135M in 2013,[58] $85M for up to 6,400 kilograms (14,100 lb) to GTO in 2014, and $90M for up to 8,000 kilograms (18,000 lb) to GTO in 2016 (with no published price for heavier GTO or any LEO payload).[59] Launch contracts typically reflect launch prices at the time the contract is signed.

In 2011, SpaceX stated that the cost of reaching low Earth orbit could be as low as US$1,000/lb if an annual rate of four launches can be sustained, and as of 2011 planned to eventually launch as many as 10 Falcon Heavy and 10 Falcon 9 annually.[43] A third launch site, intended exclusively for SpaceX private use, is planned at Boca Chica near Brownsville, Texas. SpaceX expects to start construction on the third Falcon Heavy launch facility, after final site selection, no earlier than 2014, with the first launches from the facility no earlier than 2016.[60] In late 2013, SpaceX had projected Falcon Heavy's inaugural flight to be sometime in 2014, but as of April 2017 the first launch is expected to occur in late summer 2017 due to limited manufacturing capacity and the need to deliver on the Falcon 9 launch manifest.[61][62]

By late 2013, SpaceX prices for space launch were already the lowest in the industry.[63] SpaceX's Price savings from their reused spacecraft, which could be up to 30%, could lead to a new economically driven space age.[12][64]

Scheduled launches and potential payloads

| Planned date | Payload | Customer | Outcome | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| November 2017[3] | Falcon Heavy Demo | SpaceX | No payload announced (although Elon Musk has stated that it will be the "silliest thing we can imagine").[65] | |

| Early 2018[66] | Arabsat 6A | Arabsat | Saudi Arabian communications satellite. | |

| April 30th, 2018[67] | USAF STP-2 | DoD | The mission will support the U.S. Air Force EELV certification process for the Falcon Heavy.[68] Secondary payloads include LightSail,[69] Prox-1 nanosatellite,[69] GPIM,[70][71][72] the Deep Space Atomic Clock,[73] six COSMIC-2 satellites,[74][75] and the ISAT satellite.[76] | |

| Q4, 2018[77] | Crew Dragon | Private citizens | Crewed Dragon 2 capsule with two private citizens on board. First lunar tourists, first manned Falcon Heavy. Mission will be on a free-return trajectory to the Moon. | |

| 2020[78] | ViaSat-3[79] | ViaSat |

First commercial contracts

In May 2012, SpaceX announced that Intelsat had signed the first commercial contract for a Falcon Heavy flight. It was not confirmed at the time when the first Intelsat launch would occur, but the agreement will have SpaceX delivering satellites to geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO).[80][81] In August 2016, it emerged that this Intelsat contract had been reassigned to a Falcon 9 Full Thrust mission to deliver Intelsat 35e into orbit in the third quarter of 2017.[27] Performance improvements of the Falcon 9 vehicle family since the 2012 announcement, advertising 8,300 kg to GTO for its expendable flight profile,[82] enable the launch of this 6-tonne satellite without upgrading to a Falcon Heavy variant.

In 2014, Inmarsat booked 3 launches with Falcon Heavy,[83] but due to delays they switched a payload to Ariane 5 for 2017.[84] Similarly to the Intelsat 35e case, another satellite from this contract, Inmarsat 5-F4, was switched to a Falcon 9 Full Thrust thanks to the increased liftoff capacity.[28] The remaining contract covers the launch of Inmarsat 6-F1 in 2020 on a Falcon 9.[85]

First DoD contract: USAF

In December 2012, SpaceX announced its first Falcon Heavy launch contract with the United States Department of Defense (DoD). "The United States Air Force Space and Missile Systems Center awarded SpaceX two Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV)-class missions" including the Space Test Program 2 (STP-2) mission for Falcon Heavy, originally scheduled to be launched in March 2017,[86] but later postponed to the third quarter of 2017,[87] to be placed at a near circular orbit at an altitude of ~700 km, with an inclination of 70°.[88] The Green Propellant Infusion Mission (GPIM) will be a STP-2 payload; it is a technology demonstrator project partly developed by the US Air Force.[70][89] Another secondary payload is the miniaturized Deep Space Atomic Clock.[90]

In April 2015, SpaceX sent the "U.S. Air Force an updated letter of intent April 14 outlining a certification process for its Falcon Heavy rocket to launch national security satellites." The process includes three successful flights of the Falcon Heavy including two consecutive successful flights, and states that Falcon Heavy can be ready to fly national security payloads by 2017.[91]

Crewed circumlunar flight

On February 27, 2017, SpaceX CEO Elon Musk announced that the company will attempt to fly two private citizens on a free return trajectory around the moon in late 2018.[92] The Dragon 2 spacecraft would launch on the Falcon Heavy booster. The two private citizens, who have not yet been named, approached SpaceX about taking a trip around the moon, and have "already paid a significant deposit" for the cost of the mission, according to a statement from the company. The names of the two individuals will be announced later, pending the result of initial health tests to ensure their fitness for the mission, the statement said.[77] The two passengers would be the only people on board what SpaceX expects to be about a week-long trip around the moon, according to Musk, who spoke with reporters during a phone conference. "This would be a long loop around the moon. [...] It would skim the surface of the moon, go quite a bit further out into deep space and then loop back to Earth," Musk said during the teleconference. "So I'm guessing, distance-wise, maybe [about 500,000 to 650,000 kilometers].[93] The Dragon spacecraft would operate, in large part, autonomously, but the passengers would have to train for emergency procedures. The Dragon 2 capsule will require some upgrades for the deep-space flight, but Musk said those would be limited mainly to installing a long-range communications system.

Solar System transport missions

In 2011, NASA Ames Research Center proposed a Mars mission called Red Dragon that would use a Falcon Heavy as the launch vehicle and trans-Martian injection vehicle, and a variant of the Dragon capsule to enter the Martian atmosphere. The proposed science objectives were to detect biosignatures and to drill 3.3 feet (1.0 m) or so underground, in an effort to sample reservoirs of water ice known to exist under the surface. The mission cost as of 2011 was projected to be less than US$425,000,000, not including the launch cost.[94] SpaceX announced in 2017 that propulsive landing for Dragon 2 would not be developed further, and that the capsule would not receive landing legs. Consequently, the Red Dragon missions to Mars were cancelled in favor of a larger vehicle using a different landing technqiue.[95]

Beyond the Red Dragon concept, SpaceX was expecting Falcon Heavy and Dragon 2 to carry science payloads across much of the solar system, in cislunar and inner solar system regions such as the Moon and Mars, as well as to outer solar system destinations such as Jupiter's moon Europa. SpaceX planned to transport 2,000–4,000 kg (4,400–8,800 lb) to the surface of Mars, with a soft retropropulsive landing following a limited atmospheric deceleration. When the destination has no atmosphere, the Dragon variant would dispense with the parachute and heat shield and add additional propellant.[96] With the cancellation of the Red Dragon capsule variant, those plans are now outdated.

See also

- Falcon 9 (A single core version of Falcon rocket family)

- Comparison of orbital launch systems

- Comparison of orbital launchers families

- Delta IV Heavy

- Interplanetary Transport System

- Saturn C-3

- Space Launch System

References

- 1 2 "Capabilities & Services". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Falcon Heavy". SpaceX. Retrieved 2017-04-05.

- 1 2 3 4 Elon Musk [@elonmusk] (July 28, 2017). "Falcon Heavy maiden launch this November www.instagram.com/p/BXEkGKlgJDK/" (Tweet). Retrieved July 28, 2017 – via Twitter.

- ↑ "Falcon 9". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ↑ Ahmad, Taseer; Ammar, Ahmed; Kamara, Ahmed; Lim, Gabriel; Magowan, Caitlin; Todorova, Blaga; Tse, Yee Cheung; White, Tom. "The Mars Society Inspiration Mars International Student Design Competition" (PDF). Mars Society. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- 1 2 "Falcon 9". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 2014-08-05. Retrieved 2016-04-14.

- ↑ Elon Musk [@elonmusk] (2015-12-17). "-340 F in this case. Deep cryo increases density and amplifies rocket performance. First time anyone has gone this low for O2. [RP-1 chilled] from 70F to 20 F" (Tweet). Retrieved 19 December 2015 – via Twitter.

- 1 2 3 4 "Falcon 9 Overview". SpaceX. 8 May 2010. Archived from the original on 2014-08-05.

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (March 7, 2017). "SpaceX prepares Falcon 9 for EchoStar 23 launch as SLC-40 targets return". NASASpaceFlight. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ↑ Musk, Elon. "June 2005 through September 2005 Update". SpaceX. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Musk, Elon (2008-08-16). "Transcript - Elon Musk on the future of SpaceX". Shit Elon Says. Mars Society Conference, Boulder Colorado. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- 1 2 Boozer, R.D. (2014-03-10). "Rocket reusability: a driver of economic growth". The Space Review. 2014. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- 1 2 3 "F9/Dragon: Preparing for ISS" (Press release). SpaceX. August 15, 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ↑ de Selding, Peter B. (2015-03-20). "SpaceX Aims To Debut New Version of Falcon 9 this Summer". Space News. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ SpaceX (Dec 28, 2016). "Falcon Heavy interstage being prepped at the rocket factory. When FH flies next year, it will be the most powerful operational rocket in the world by a factor of two". Instagram. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ "Falcon Heavy Test Stand". Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- ↑ Berger, Eric (9 May 2017). "SpaceX proves Falcon Heavy is indeed a real rocket with a test firing". Ars Technica. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ↑ "SpaceX on Twitter". Twitter. Retrieved 2017-05-13.

- ↑ "US co. SpaceX to build heavy-lift, low-cost rocket". Reuters. 5 April 2011. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ↑ "SpaceX announces launch date for the world's most powerful rocket" (Press release). SpaceX. April 5, 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (2015-09-02). "First Falcon Heavy Launch Scheduled for Spring". Space News. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ↑ "Launch Schedule". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 2016-01-01. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (2016-02-04). "SpaceX seeks to accelerate Falcon 9 production and launch rates this year". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (August 9, 2016). "Pad hardware changes preview new era for Space Coast". NASA Spaceflight. Retrieved August 16, 2016.

- ↑ "SpaceX is pushing back the target launch date for its first Mars mission". Space.com. 17 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ↑ de Selding, Peter B. (June 26, 2017). "SpaceX’s Shotwell: 1 Falcon Heavy demo this year; satellite broadband remains ‘on the side’". Space Intel Report. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- 1 2 Clark, Stephen (30 August 2016). "SES agrees to launch satellite on ‘flight-proven’ Falcon 9 rocket". Spaceflight Now.

- 1 2 de Selding, Peter B. (3 November 2016). "Inmarsat, juggling two launches, says SpaceX to return to flight in December". SpaceNews. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ "Arabsat contracts go to Lockheed Martin, Arianespace and SpaceX". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 2015-05-05.

- ↑ https://www.space.com/37550-elon-musk-spacex-falcon-heavy-maiden-launch.html

- ↑ https://www.space.com/37550-elon-musk-spacex-falcon-heavy-maiden-launch.html

- ↑ "SpaceX Announces Launch Date for the World's Most Powerful Rocket". Spaceref.com. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- ↑ "Falcon Heavy". SpaceX. 2015. Retrieved 2016-04-29.

- ↑ "Octaweb". SpaceX News. 2013-04-12. Retrieved 2013-08-02.

- 1 2 "Landing Legs". SpaceX News. 2013-04-12. Retrieved 2013-08-02.

- ↑ Kremer, Ken (27 January 2015). "Falcon Heavy Rocket Launch and Booster Recovery Featured in Cool New SpaceX Animation". Universe Today. Universe Today. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ↑ Nield, George C. (April 2014). Draft Environmental Impact Statement: SpaceX Texas Launch Site (PDF) (Report). 1. Federal Aviation Administration, Office of Commercial Space Transportation. pp. 2–3. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013.

- 1 2 Simberg, Rand (2012-02-08). "Elon Musk on SpaceX’s Reusable Rocket Plans". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 2012-02-07.

- ↑ "Seeking a Human Spaceflight Program Worthy of a Great Nation" (PDF). NASA. October 2009. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- 1 2 Clark, Stephen (April 5, 2011). "SpaceX enters the realm of heavy-lift rocketry". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- 1 2 "Space Exploration Technologies Corporation - Falcon Heavy". SpaceX. 2011-12-03. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ "SpaceX Brochure" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-06-14.

- 1 2 "SpaceX Press Conference". SpaceX. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- ↑ "Feasibility of a Dragon-derived Mars lander for scientific and human-precursor investigations" (PDF). 8m.net. October 31, 2011. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ↑ "Capabilities & Services". SpaceX. 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-10-07. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- ↑ "Capabilities & Services". SpaceX. 2017. Retrieved 2017-04-05.

- ↑ Strickland, John K., Jr. (September 2011). "The SpaceX Falcon Heavy Booster". National Space Society. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ "SpaceX Announces Launch Date for the World's Most Powerful Rocket". SpaceX. 2011-04-05. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ↑ Logsdon, Tom (1998). Orbital Mechanics - Theory and Applications. New York: Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0-471-14636-0. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Elon Musk (1 May 2016). ""Does FH expendable performance include crossfeed?" "No cross feed. It would help performance, but is not needed for these numbers."". Twitter. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Chris Bergin (January 12, 2009). "Musk ambition: SpaceX aim for fully reusable Falcon 9". NASAspaceflight. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Stephen Clark (March 31, 2017). "SpaceX flies rocket for second time in historic test of cost-cutting technology". SpaceFlightNow. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Elon Musk (31 Mar 2017). ""Considering trying to bring upper stage back on Falcon Heavy demo flight for full reusability. Odds of success low, but maybe worth a shot."". Twitter. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Svitak, Amy (2013-03-05). "Falcon 9 Performance: Mid-size GEO?". Aviation Week. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Testimony of Elon Musk (May 5, 2004). "Space Shuttle and the Future of Space Launch Vehicles". U.S. Senate. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Sietzen, Frank, Jr. (March 18, 2001). "Spacelift Washington: International Space Transportation Association Faltering; The myth of $10,000 per pound". SpaceRef. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Brian Wang (March 22, 2013). "Upgraded Spacex Falcon 9.1.1 will launch 25% more than old Falcon 9 and bring price down to $4109 per kilogram to LEO". NextBigFuture. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-10-07. Retrieved 2013-09-28.. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- ↑ "Capabilities and Services". SpaceX. May 3, 2016. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (2013-04-01). "The great state space race". The Space Review. Retrieved 2013-04-03.

- ↑ Svitak, Amy (2014-03-05). "SpaceX to Compete for Air Force Launches This Year". Aviation Week. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ Svitak, Amy (2014-03-10). "SpaceX Says Falcon 9 To Compete For EELV This Year". Aviation Week. Retrieved 2014-03-11.

- ↑ Belfiore, Michael (December 9, 2013). "The Rocketeer". Foreign Policy; Feature article. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- ↑ Messier, Doug (January 14, 2014). "Shotwell: Reusable Falcon 9 Would Cost $5 to $7 Million Per Launch". Parabolic Arc. Retrieved 2014-01-15.

- ↑ Berger, Eric (April 2, 2017). "SpaceX to launch "silliest thing we can imagine" on debut Falcon Heavy". arstechnica.

- ↑ "Interview with Gwynne Shotwell On the Space Show". 22 Jun 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ "LightSail 2 updates: Prox-1 mission changes, new launch date". www.planetary.org. Retrieved 2017-07-21.

- ↑ Leone, Dan (2014-07-24). "Solar Probe Plus, NASA's ‘Mission to the Fires of Hell,’ Trading Atlas 5 for Bigger Launch Vehicle". Space News. Retrieved 2014-07-25.

- 1 2 "Lightsail". Planetary Society. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- 1 2 "About Green Propellant Infusion Mission (GPIM)". NASA. 2014. Retrieved 2014-02-26.

- ↑ "Green Propellant Infusion Mission (GPIM)". Ball Aerospace. 2014. Retrieved 2014-02-26.

- ↑ "The Green Propellant Infusion Mission (GPIM)" (PDF). Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp. March 2013. Retrieved 2014-02-26.

- ↑ "Deep Space Atomic Clock". NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 27 April 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- ↑ "SpaceX Awarded Two EELV-Class Missions From The United States Air Force". SpaceX. Dec 5, 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ "FORMOSAT 7 / COSMIC-2". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ "Falcon overloaded with knowledge – Falcon Heavy rocket under the Space Test Program 2 scheduled in October 2016". Spaceflights News. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- 1 2 "SpaceX To Send Privately Crewed Dragon Spacecraft Beyond The Moon Next Year". SpaceX. Feb 27, 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Peter B. de Selding (February 10, 2016). "ViaSat details $1.4-billion global Ka-band satellite broadband strategy to oust incumbent players". SpaceNews. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Third Quarter Fiscal Year 2016 Results". ViaSat. February 9, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- ↑ "SpaceX Announces First Commercial Contract For Launch In 2013". Red Orbit. 2012-05-30. Retrieved 2012-12-15.

- ↑ "Intelsat Signs First Commercial Falcon Heavy Launch Agreement With SpaceX" (Press release). SpaceX. 2012-05-29. Retrieved 2012-12-16.

- ↑ "Falcon 9". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 5 August 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ de Selding, Peter B. (July 2, 2014). "Inmarsat Books Falcon Heavy for up to Three Launches". SpaceNews. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (8 December 2016). "Inmarsat shifts satellite from SpaceX to Arianespace". SpaceNews.

- ↑ Krebs, Gunter. "Inmarsat-6 F1, 2". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ David, Leonard (April 13, 2016). "Spacecraft Powered by 'Green' Propellant to Launch in 2017". Space.com. Retrieved 2016-04-15.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (9 August 2016). "SpaceX offers large rockets for small satellites". SpaceNews. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ↑ "DSAC (Deep Space Atomic Clock)". NASA. Earth Observation Resources. 2014. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- ↑ "Green Propellant Infusion Mission Project" (PDF). NASA. July 2013. Retrieved 2014-02-26.

- ↑ "Deep Space Atomic Clock". NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. April 27, 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- ↑ Gruss, Mike (2015-04-15). "SpaceX Sends Air Force an Outline for Falcon Heavy Certification". Space News. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ↑ Kenneth Chang (Feb 27, 2017). "SpaceX Plans to Send 2 Tourists Around Moon in 2018". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Calla Cofield (February 27, 2017). "SpaceX to Fly Passengers On Private Trip Around the Moon in 2018". Space.com. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Wall, Mike (2011-07-31). "'Red Dragon' Mission Mulled as Cheap Search for Mars Life". SPACE.com. Retrieved 2011-07-31.

- ↑ Elon Musk suggests SpaceX is scrapping its plans to land Dragon capsules on Mars The Verge July 19, 2017

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (2015-05-11). "Falcon Heavy enabler for Dragon solar system explorer". NASASpaceFlight. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

External links

- Falcon Heavy official page

- Falcon Heavy flight animation, January 2015.