Soviet calendar

While the Gregorian calendar was implemented in Soviet Russia in February 1918 by dropping the Julian dates of 1–13 February 1918 pursuant to a Sovnarkom decree, the Soviet calendar added five- and six-day work weeks between 1929 and 1940. Although the traditional seven-day week was still recognized, a day of rest on Sunday was replaced by one day of rest in each work week. Many sources erroneously state that the weeks were organized into 30-day months.

History

Gregorian calendar

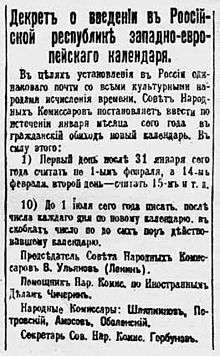

"Western European calendar"

(click on image for translation)

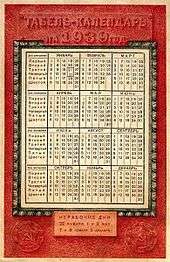

The Gregorian calendar was implemented in Russia on 14 February 1918 by dropping the Julian dates of 1–13 February 1918 pursuant to a Sovnarkom decree signed 24 January 1918 (Julian) by Vladimir Lenin. The decree required that the Julian date was to be written in parentheses after the Gregorian date until 1 July 1918.[1] All surviving examples of physical calendars from 1929–40 show the irregular month lengths of the Gregorian calendar (such as those displayed here). Most calendars displayed all the days of a Gregorian year as a grid with seven rows or columns for the traditional seven-day week with Sunday first.

Numbered five-day work week,

excluding five national holidays

The 1931 pocket calendar displayed here is a rare example that excluded the five national holidays, enabling the remaining 360 days of the Gregorian year to be displayed as a grid with five rows labeled I–V for each day of the five-day week.[2] Even it had the full Gregorian calendar on the other side. Throughout this period, Pravda, the official newspaper of the Communist Party, and other newspapers continued to use Gregorian calendar dates in their mastheads alongside the traditional seven-day week.[3][4] Pravda dated individual issues with 31 January, 31 March, 31 May, 31 July, 31 August, 31 October, and 31 December, but never used 30 February during the period 1929–1940. The traditional names of "Resurrection" (Воскресенье) for Sunday and "Sabbath" (Суббота) for Saturday continued to be used, despite the government's officially anti-religious atheistic policy. In rural areas, the traditional seven-day week continued to be used despite official disfavor.[3][4][5] Several sources from the 1930s state that the old Gregorian calendar was not changed.[3][6][7] Two modern sources explicitly state that the structure of the Gregorian calendar was not touched.[8][9]

12 December 1937

"Sixth day of the six-day week" (just below "12")

—————————

"Election day for the Supreme Soviet of the USSR"

22 October 1935

"Fourth day of the six-day week" (just below "ОКТЯБРЬ")

During the second half of May 1929, Yuri Larin (Юрий Ларин, 1882–1932) proposed a continuous production week (nepreryvnaya rabochaya nedelya = nepreryvka) to the Fifth Congress of Soviets of the Union, but so little attention was paid to his suggestion that the president of the Congress did not even mention it in his final speech. By the beginning of June 1929, Larin had won the approval of Joseph Stalin, prompting all newspapers to praise the idea. The change was advantageous to the anti-religious movement, as Sundays and religious holidays became working days.[10] On 8 June 1929 the Supreme Economic Council of the RSFSR directed its efficiency experts to submit within two weeks a plan to introduce continuous production. Before any plan was available, during the first half of June 1929, 15% of industry had converted to continuous production according to Larin, probably an overestimate. On 26 August 1929 the Council of People's Commissars (CPC) of the Soviet Union (Sovnarkom) declared "it is essential that the systematically prepared transition of undertakings and institutions to continuous production should begin during the economic year 1929–1930".[11][12] The lengths of continuous production weeks were not yet specified, and the conversion was only to begin during the year. Nevertheless, many sources state that the effective date of five-day weeks was 1 October 1929,[4][13][14][5][15][16] which was the beginning of the economic year. But many other lengths of continuous work weeks were used, all of which were gradually introduced.

Implementation of continuous production weeks

Specific lengths for continuous production weeks were first mentioned when rules for the five-day continuous work week were issued on 24 September 1929. On 23 October 1929 building construction and seasonal trades were put on a continuous six-day week, while factories that regularly halted production every month for maintenance were put on six- or seven-day continuous production weeks. In December 1929, it was reported that about 50 different versions of the continuous work week were in use, the longest being a 'week' of 37 days (30 continuous days of work followed by seven days of rest). By the end of 1929, orders were issued that the continuous week was to be extended to 43% of industrial workers by 1 April 1930 and to 67% by 1 October 1930. Actual conversion was more rapid, 63% by 1 April 1930. In June 1930 it was decreed that the conversion of all industries was to be completed during the economic year 1930–31, except for the textile industry. But on 1 October 1930 peak usage was reached, with 72.9% of industrial workers on continuous schedules. Thereafter, usage decreased. All of these official figures were somewhat inflated because some factories said they adopted the continuous week without actually doing so. The continuous week was applied to retail and government workers as well, but no usage figures were ever published.[11][17][18]

Implementation of six-day weeks

As early as May 1930, while usage of the continuous week was still advancing, some factories reverted to an interrupted week. On 30 April 1931, one of the largest factories in the Soviet Union was put on an interrupted six-day week (Шестидневка = shestidnevka). On 23 June 1931, Stalin condemned the continuous work week as then practiced, supporting the temporary use of the interrupted six-day week (one common rest day for all workers) until the problems with the continuous work week could be resolved. During August 1931, most factories were put on an interrupted six-day week as the result of an interview with the People's Commissar for Labor, who severely restricted the use of the continuous week. The official conversion to non-continuous schedules was decreed by the Sovnarkom of the USSR somewhat later, on 23 November 1931.[15][18][19] Institutions serving cultural and social needs and those enterprises engaged in continuous production such as ore smelting were exempted.[20] It is often stated that the effective date of the interrupted six-day work week was 1 December 1931,[21][22][13][5][15][19] but that is only the first whole month after the 'official conversion'. The massive summer 1931 conversion made this date after-the-fact and some industries continued to use continuous weeks. The last figures available indicate that on 1 July 1935 74.2% of all industrial workers were on non-continuous schedules (almost all six-day weeks) while 25.8% were still on continuous schedules. Due to a decree dated 26 June 1940, the traditional interrupted seven-day week with Sunday as the common day of rest was reintroduced on 27 June 1940.[1][2][18][23]

Five-day weeks

Colored five-day work week

Days grouped into seven-day weeks

One national holiday in black, four with white numbers

One worker's red rest days of the five-day work week

Each day of the five-day week was labeled by either one of five colors or a Roman numeral from I to V. Each worker was assigned a color or number to identify his or her day of rest.

Eighty per cent of each factory's workforce was at work every day (except holidays) in an attempt to increase production while 20% were resting. But if a husband and wife, and their relatives and friends, were assigned different colors or numbers, they would not have a common rest day for their family and social life. Furthermore, machines broke down more frequently both because they were used by workers not familiar with them, and because no maintenance could be performed on machines that were never idle in factories with continuous schedules (24 hours/day every day). Five-day weeks (and later six-day weeks) "made it impossible to observe Sunday as a day of rest. This measure was deliberately introduced 'to facilitate the struggle to eliminate religion'".[24]

The colors vary depending on the source consulted. The 1930 color calendar displayed here has days of purple, blue, yellow, red, and green, in that order beginning 1 January.[25] Blue was supported by an anonymous writer in 1936 as the second day of the week, but he stated that red was the first day of the week.[3] However, most sources replace blue with either pink,[21][4][22][13][26] orange,[6][14][5] or peach,[15] all of which specify the different order yellow, pink/orange/peach, red, purple, and green. The partial 1930 black and white calendar from Kingsbury and Fairchild (1935) displayed here does not conform to any of these because its red day is the fifth day of the week, which even disagrees with their own statement that red was the third day of the week.[6]

Six-day weeks

Days grouped into seven-day weeks

Rest day of six-day work week in blue

Five national holidays in red

Days grouped into six-day work weeks

Each day 31 is outside six-day week

Last six-day week of February is short

Six national holidays in red

From the summer of 1931 until 26 June 1940, each Gregorian month was usually divided into five six-day weeks, more and less (as shown by the 1933 and 1939 calendars displayed here).[25] The sixth day of each week was a uniform day off for all workers, that is days 6, 12, 18, 24, and 30 of each month. The last day of 31-day months was always an extra work day in factories, which, when combined with the first five days of the following month, made six successive work days. But some commercial and government offices treated the 31st day as an extra day off. To make up for the short fifth week of February, 1 March was a uniform day off followed by four successive work days in the first week of March (2–5). The partial last week of February had four work days in common years (25–28) and five work days in leap years (25–29). But some enterprises treated 1 March as a regular work day, producing nine or ten successive work days between 25 February and 5 March, inclusive. The dates of the five national holidays did not change, but they now converted five regular work days into holidays within three six-day weeks rather than splitting those weeks into two parts (none of these holidays was on a "sixth day").[3][4][6]

National holidays

On 10 December 1918 six Bolshevik holidays were decreed during which work was prohibited.[27][28]

- 1 January – New Year's Day

- 22 January – Day of 9 January 1905

- Commemorates Bloody Sunday on 9 January 1905 (Julian) or 22 January 1905 (Gregorian)

- 12 March – Day of the Overthrow of the Autocracy

- Commemorates the mutiny of the Imperial Guards (about 60,000 soldiers) in Petrograd (now Saint Petersburg) on 27 February 1917 (Julian) or 12 March 1917 (Gregorian) during the February Revolution

- 18 March – Day of the Paris Commune

- Commemorates the uprising of the National Guard of Paris on 18 March 1871 (Gregorian) which established the Paris Commune

- 1 May – Day of the International[29]

- Celebration within Russia and later the Soviet Union of International Workers' Day

- 7 November – Day of the Proletarian Revolution

- Commemorates the Bolshevik uprising on 25 October 1917 (Julian) or 7 November 1917 (Gregorian)

In January 1925, the anniversary of Lenin's Death in 1924 was added on 21 January. Although other events were commemorated on other dates, they were not days of rest. Originally, the "May holidays" and "November holidays" were one day each (1 May and 7 November), but both were extended from one to two days in 1928, making 2 May and 8 November public holidays as well.[30]

Until 1929, regional labor union councils or local governments were authorized to set up additional public holidays, totaling to up to 10 days a year. Although people would not work on those days, they would not be paid holidays.[31][32] Typically, at least some of these days were used for religious feast, typically those of the Russian Orthodox Church, but in some localities possibly those of other religions as well.[33]

On 24 September 1929, three holidays were eliminated, 1 January, 12 March, and 18 March. Lenin's Day on 21 January was merged with 22 January. The resulting five holidays continued to be celebrated until 1951, when 22 January ceased to be a holiday. See История праздников России (History of the festivals of Russia).[3][4][6][27][11][34][35]

- 22 January – Day of Remembrance of 9 January 1905 and of the Memory of V.I. Lenin

- Commemorates Bloody Sunday on 9 January 1905 (Julian) or 22 January 1905 (Gregorian) and the death of Vladimir Lenin on 21 January 1925 (Gregorian)

- 1–2 May – Days of the International

- 7–8 November – Days of the Anniversary of the October Revolution

Two Journal of Calendar Reform articles (1938 and 1943) have two misunderstandings, specifying 9 January and 26 October, not realizing that both are Julian calendar dates equivalent to the unspecified Gregorian dates 22 January and 8 November, so they specify 9 January, 21 January, 1 May, 26 October, and 7 November, plus a quadrennial leap day.[21][22]

Erroneous 30-day months

A 1929 Time magazine article reporting Soviet five-day work weeks, which it called an "Eternal calendar", associated them with the French Republican Calendar, which had months containing three ten-day weeks.[36] In February 1930 a government commission proposed a "Soviet revolutionary calendar" containing twelve 30-day months plus five national holidays that were not part of any month, but it was rejected because it would differ from the Gregorian calendar used by the rest of Europe.[17] Four Journal of Calendar Reform articles (1938, 1940, 1943, 1954) thought that five-day weeks actually were organized into 30-day months,[21][4][22][37] as do several modern sources.[13][26][5][38]

A 1931 Time magazine article reporting six-day weeks stated that they too were organized into 30-day months, with the five national holidays between those months.[39] Two of the Journal of Calendar Reform articles (1938 and 1943) thought that six-day as well as five-day weeks were organized into 30-day months.[21][22] A couple of modern sources state that five-day weeks plus the first two years of six-day weeks were organized into 30-day months.[14][34]

Apparently to place the five national holidays between 30-day months since 1 October 1929, Parise (1982) shifted Lenin's Day to 31 January, left two Days of the Proletariat on 1–2 May, and shifted two Days of the Revolution to 31 October and 1 November, plus 1 January (all Gregorian dates).[14] Stating that all months had 30 days between 1 October 1929 and 1 December 1931, the Oxford Companion to the Year (1999) 'corrected' Parise's list by specifying that "Lenin Day" was after 30 January (31 January Gregorian), a two-day "Workers' First of May" was after 30 April (1–2 May Gregorian), two "Industry Days" were after 7 November (8–9 November Gregorian), and placed the leap day after 30 February (2 March Gregorian).[13][26]

References

- 1 2 История календаря в России и в СССР (Calendar history in Russia and the USSR), chapter 19 in История календаря и хронология by Селешников (History of the calendar and chronology by Seleschnikov) (in Russian). ДЕКРЕТ "О ВВЕДЕНИИ ЗАПАДНО-ЕВРОПЕЙСКОГО КАЛЕНДАРЯ" (Decree "On the introduction of the Western European calendar") contains the full text of the decree (in Russian).

- 1 2 ИЗ ИСТОРИИ ОТЕЧЕСТВЕННОГО КАРМАННОГО КАЛЕНДАРЯ by Дмитрий Малявин ("Calendar stories from reforms in the USSR" by Dmitry Malyavin) (in Russian) Does not mention colors, only numbers.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The Riga correspondent of the London Times, "Russian experiments", Journal of Calendar Reform 6 (1936) 69–71.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Albert Parry, "The Soviet calendar", Journal of Calendar Reform 10 (1940) 65–69.

- 1 2 3 4 5 E. G. Richards, Mapping time, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998) 159–160, 277–279.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Susan M. Kingsbury and Mildred Fairchild, Factory family and woman in the Soviet Union (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1935) 245–248. Attributes the rest days of six-day weeks to five-day weeks.

- ↑ P. Malevsky-Malevitch, Russia U.S.S.R.: A complete handbook (New York: William Farquhar Payson, 1933) 601–602.

- ↑ Lance Latham, Standard C date/time library: Programming the world's calendars and clocks (Lawrence, KS: R&D Books, 1998) 390–392.

- ↑ Toke Nørby, The Perpetual Calendar: A helpful tool to postal historians: What about Russia?

- ↑ Siegelbaum, Lewis H. (1992). Soviet State and Society Between Revolutions, 1918-1929. Cambridge University Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-521-36987-9.

- 1 2 3 [Solomon M. Schwarz], "The continuous working week in Soviet Russia", International Labour Review 23 (1931) 157–180.

- ↑ Gary Cross, Worktime and industrialization (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1988) 202–205.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bonnie Blackburn and Leofranc Holford-Strevens, The Oxford companion to the year (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999) 99, 688–689.

- 1 2 3 4 Frank Parise, ed., "Soviet calendar", The book of calendars, (New York: Facts on file, 1982) 377.

- 1 2 3 4 Eviatar Zerubavel, "The Soviet five-day Nepreryvka", The seven day circle (New York: Free press, 1985) 35–43.

- ↑ The Duchess of Atholl (Katherine Atholl), The conscription of a people (1931) 84–86, 107.

- 1 2 R. W. Davies, The Soviet economy in turmoil, 1929–1930 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press, 1989) 84–86, 143–144, 252–256, 469, 544.

- 1 2 3 Solomon M. Schwarz, Labor in the Soviet Union (New York: Praegar, 1951) 258–277.

- 1 2 Elisha M. Friedman, Russia in transition: a business man's appraisal (New York: Viking Press, 1932) 260–262.

- ↑ Handbook of the Soviet Union (New York: American-Russian Chamber of Commerce, 1936) 524, 526.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Erland Echlin, "Here all nations agree", Journal of Calendar Reform 8 (1938) 25–27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Carleton J. Ketchum, "Russia's changing tide", Journal of Calendar Reform 13 (1943) 147–155.

- ↑ On the transfer to the seven-day work week, 26 June 1940 (item 2)

- ↑ Nicolas Werth, The Black Book of Communism (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1999) 172.

- 1 2 Clive Foss, "Stalin's topsy-turvy work week", History Today 54/9 (September 2004) 46–47.

- 1 2 3 La réforme grégorienne: La réforme en Russie (The Gregorian reform: The reform in Russia) (in French)

- 1 2 Irina Shilova, "Building the Bolshevik calendar through Pravda and Izvestiia", Toronto Slavic Quarterly No. 19 (Winter 2007). She named the holidays associated with five- and six-day weeks the "Stalin calendar" to distinguish them from the holidays of the previous eleven years, which she called the "Bolshevik calendar".

- ↑ ПРАВИЛА ОБ ЕЖЕНЕДЕЛЬНОМ ОТДЫХЕ И О ПРАЗДНИЧНЫХ ДНЯХ (Rules concerning weekly rest days and holidays) (in Russian) Last annex.

- ↑ The name of the holiday is uniformly given in Russian sources as "день Интернационала" (e.g., in А.И. Щербинин (A.I. Shcherbinin) «КРАСНЫЙ ДЕНЬ КАЛЕНДАРЯ»: ФОРМИРОВАНИЕ МАТРИЦЫ ВОСПРИЯТИЯ ПОЛИТИЧЕСКОГО ВРЕМЕНИ В РОССИИ ("The red day in the calendar": the formation of the political time perception matrix in Russia)), and is somewhat quaintly translated by Shilova (2007) as "Day of International". The name could probably be translated literally as "Day of the International", where "the International" initially (1918) may not have directly referred to either the already defunct Second International or to the Third International (which was yet to be officially established), but to the general idea of an international Labor/Communist solidarity organization. Incidentally, the name of the international Communist anthem, The Internationale, is spelled the same way in Russian.

- ↑ Постановление ВЦИК, СНК РСФСР 30.07.1928 «Об изменении статей 111 и 112 Кодекса законов о труде РСФСР». (Order of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and the Council of the People's Commissars of the RSFSR, "Regarding changes of Articles 111 and 112 of the Labor Code of the RSFSR"). Presumably, other member republics of the USSR passed similar legislation as well.

- ↑ RSFSR Labor Code (1918), Article 8. (in Russian) Also quoted in Shcherbinin, p. 57.

- ↑ Декрет СНК РСФСР от 17.06.1920 «Общее положение о тарифе (Правила об условиях найма и оплаты труда рабочих и служащих всех предприятий, учреждений и хозяйств в РСФСР).» (Decree of the Council of the People's Commissars of the RSFSR, "General [wage] rate regulations (Regulations of the conditions of hire and paying of wages of the employees of all enterprises, organizations, and farm estates in the RSFSR)".

- ↑ Shcherbinin, p. 57

- 1 2 Duncan Steel, Marking Time (New York: John Wiley, 2000) 293–294.

- ↑ ПОСТАНОВЛЕНИЕ от 24 сентября 1929 года: О РАБОЧЕМ ВРЕМЕНИ И ВРЕМЕНИ ОТДЫХА В ПРЕДПРИЯТИЯХ И УЧРЕЖДЕНИЯХ, ПЕРЕХОДЯЩИХ НА НЕПРЕРЫВНУЮ ПРОИЗВОДСТВЕННУЮ НЕДЕЛЮ (Decree of 24 September 1929: Hours of work and leisure time in the enterprises and institutions switching to the continuous production week) (in Russian)

- ↑ Oneday, Twoday (Time: 7 October 1929)

- ↑ Elisabeth Achelis, "Calendar marches on: Russia's difficulties", Journal of Calendar Reform 24 (1954) 91–93.

- ↑ The Orthodox and Soviet Calendar Reforms

- ↑ Staggers Unstaggers (Time: 7 December 1931)