Southern Pacific Transportation Company

.png) | |

|

SP system map (before the 1988 DRGW merger) | |

| Reporting mark | SP |

|---|---|

| Locale | Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Illinois, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas, Utah |

| Dates of operation | 1865–1996 |

| Successor | Union Pacific |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge with some 3 ft (914 mm) gauge branches |

| Headquarters | San Francisco, California |

The Southern Pacific Transportation Company (reporting mark SP), earlier Southern Pacific Railroad and Southern Pacific Company, and usually called the Southern Pacific or (from the railroad's initials) Espee, was an American Class I railroad. It was absorbed in 1988 by the company that controlled the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad and eight years later became part of the Union Pacific Railroad.

The railroad was founded as a land holding company in 1865, later acquiring the Central Pacific Railroad by lease. By 1900 the Southern Pacific Company was a major railroad system incorporating many smaller companies, such as the Texas and New Orleans Railroad and Morgan's Louisiana and Texas Railroad. It extended from New Orleans through Texas to El Paso, across New Mexico and through Tucson, to Los Angeles, through most of California, including San Francisco and Sacramento. Central Pacific lines extended east across Nevada to Ogden, Utah, and reached north through Oregon to Portland. Other subsidiaries eventually included the St. Louis Southwestern Railway (Cotton Belt), the Northwestern Pacific Railroad at 328 miles (528 km), the 1,331 miles (2,142 km) Southern Pacific Railroad of Mexico, and a variety of 3 ft (914 mm) narrow gauge routes.

In 1929 SP/T&NO operated 13848 route-miles not including Cotton Belt, whose purchase of the Golden State Route circa 1980 nearly doubled its size to 3,085 miles (4,965 km), bringing total SP/SSW mileage to around 13,508 miles (21,739 km).

By the 1980s route mileage had dropped to 10,423 miles (16,774 km), mainly due to the pruning of branch lines. In 1988 the Southern Pacific was taken over by D&RGW parent Rio Grande Industries. The combined railroad kept the Southern Pacific name due to its brand recognition in the railroad industry and with customers of both constituent railroads. Along with the addition of the SPCSL Corporation route from Chicago to St. Louis, the total length of the D&RGW/SP/SSW system was 15,959 miles (25,684 km).

By 1996 years of financial problems had dropped SP's mileage to 13,715 miles (22,072 km), and it was taken over by the Union Pacific Railroad.

The SP was the defendant in the landmark 1886 United States Supreme Court case Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad which is often interpreted as having established certain corporate rights under the Constitution of the United States.

Southern Pacific founded important hospitals in San Francisco, Tucson, and elsewhere. In the 1970s, it also founded a telecommunications network with a state-of-the-art microwave and fiber optic backbone. This evolved into Sprint, a company whose name came from the acronym for Southern Pacific Railroad Internal Networking Telephony.[1]

Timeline

Origins

.jpg)

One of the original ancestor-railroads of SP, the Galveston and Red River Railway (GRR), was chartered on 11 March 1848 by Ebenezer Allen,[2][3][4][5] although the company did not become active until 1852 after a series of meetings at Chappell Hill, Texas and Houston, Texas. The original aim was to construct a railroad from Galveston Bay to a point on the Red River near a trading post known as Coffee's Station.[4] Ground was broken in 1853.[5] The GRR built 2 miles (3.2 km) of track in Houston in 1855.[4] Track laying began in earnest in 1856 and on 1 September 1856 GRR was renamed the Houston and Texas Central Railway (H&TC).[5] SP acquired H&TC in 1883 but it continued to operate as a subsidiary under its own management until 1927,[5] when it was leased to another SP-owned railroad, the Texas and New Orleans Railroad.

The Buffalo Bayou, Brazos and Colorado Railway (BBB&C), was chartered in Texas on 11 February 1850 by a group that included General Sidney Sherman.[2][6] BBB&C was the first railroad to commence operation in Texas and the first component of SP to commence operation. Surveying of the route alignment commenced at Harrisburg, Texas in 1851 and construction between Houston and Alleyton, Texas commenced later that year. The first 20 miles (32 km) of track opened in August 1853.[6]

SP was founded in San Francisco, California in 1865 by a group of businessmen led by Timothy Phelps with the aim of building a rail connection between San Francisco and San Diego, California. The company was purchased in September 1868 by a group of businessmen known as the Big Four: Charles Crocker, Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins, Jr. and C. P. Huntington. The Big Four had, in 1861, created the Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR). CPRR was merged into SP in 1870.

- June 1873: The Southern Pacific builds its first locomotive at the railroad's Sacramento shops as CP's 2nd number 55, a 4-4-0.

- November 8, 1874: Southern Pacific tracks reach Bakersfield, California and work begins on the Tehachapi Loop.

- September 5, 1876: The first through train from San Francisco arrives in Los Angeles, California after traveling over the newly completed Tehachapi Loop.

- 1877: Southern Pacific tracks from Los Angeles cross the Colorado River at Yuma, Arizona. Southern Pacific purchases the Houston and Texas Central Railway.

- 1879: Southern Pacific engineers experiment with the first oil-fired locomotives.

- March 20, 1880: The first Southern Pacific train reaches Tucson, Arizona.

- May 11, 1880: The Mussel Slough Tragedy (a dispute over property rights with SP) takes place in Hanford, California.

- 1881: Southern Pacific gains control of the Texas and New Orleans Railroad and the Louisiana Western Railroad.[7]

- May 19, 1881: Southern Pacific tracks reach El Paso, Texas, beating the rival Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway to El Paso.

- December 15, 1881: Southern Pacific (under the GH&SA RR) meets the Texas and Pacific at Sierra Blanca, Texas in Hudspeth County, Texas getting close to completing the nation's second transcontinental railroad.

- January 12, 1883: The Southern section of the second transcontinental railroad line is completed as the Southern Pacific tracks from Los Angeles meet the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railway at a location three miles West of the Pecos River near to Langtry, Texas. The sterling silver spikes were alternatively driven by James Campbell and James Converse with the other driven by Col. Tom Pierce, the GH&SA president. These spikes were thereafter quickly removed. This became the first year round all weather transcontinental railroad. Almost ten years later, March 31, 1892 the Pecos River High Bridge was opened. This moved the line up and out of the Rio Grande Canyon and simplified the alignment. The line now extends to San Antonio and Houston along the Sunset Route.

- March 17, 1884: The Southern Pacific is incorporated in Kentucky.

- February 17, 1885: The Southern Pacific and Central Pacific are combined under a holding company named the Southern Pacific Company.

- April 1, 1885: The Southern Pacific takes over all operation of the Central Pacific. Effectively, the CP no longer exists as a separate company.

- 1886: The first refrigerator cars on the Southern Pacific enter operation; the loading of refrigerator cars with oranges, first performed at Los Angeles, California on February 14, contributed to an economic boom in the famous citrus industry of Southern California, by making deliveries of perishable fruits and vegetables to the eastern United States possible.

- 1886: Southern Pacific wins the landmark Supreme Court case Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad which establishes equal rights under the law to corporations.

- 1887: Southern Pacific gains full control of the Oregon and California Railroad giving it a route through northern California all the way across Oregon to Oregon main port city of Portland. However, outright ownership of the railroad wouldn't occur until 1927.

- 1893: Southern Pacific train bandits John Sontag and Chris Evans are apprehended in the Battle of Stone Corral near Visalia, California.[8]

- 1898: Sunset magazine is founded as a promotional tool of the Southern Pacific.

- October 1899: Southern Pacific gains control of the Houston East and West Texas Railway.[9]

- 1901: Frank Norris' novel, The Octopus: A California Story, a fictional retelling of the Mussel Slough Tragedy and the events leading up to it, is published.

- July 6, 1901: The Southern Pacific Terminal Company is chartered as an independent operating entity to provide rail service to the Southern Pacific's steamer docks in Galveston, Texas.[10]

- 1901: Union Pacific Railroad acquires control of Southern Pacific. In the following years, many SP operating procedures and equipment purchases follow patterns established by Union Pacific.

- 1903: Southern Pacific gains 50% control of the Pacific Electric system in Los Angeles.

- March 8, 1904: SP opens the Lucin Cutoff across the Great Salt Lake, bypassing Promontory, UT for the railroad's mainline.

- March 20, 1904: SP's Coast Line is completed between Los Angeles and Santa Barbara, CA.

- April 18, 1906: The great 1906 San Francisco earthquake strikes, damaging the railroad's headquarters building and destroying the mansions of the now-deceased Big Four.

- 1906: SP and UP jointly form the Pacific Fruit Express (PFE) refrigerator car line.

- May 22, 1907: The Coast Line Limited of the Southern Pacific Railroad is derailed west of Glendale, California. The accident causes several deaths and injuries, and its cause linked to anarchists.

- 1907: With Santa Fe, Southern Pacific forms Northwestern Pacific, unifying several SP- and Santa Fe-owned subsidiaries into one jointly owned railroad serving northwestern California.

- 1909: The Southern Pacific of Mexico, the railroad's subsidiary south of the U.S. border, is incorporated.

- 1913: The Supreme Court of the United States orders the Union Pacific to sell all of its stock in the Southern Pacific.

.jpg)

- 1917: Southern Pacific moves into its new headquarters in San Francisco at One Market Street

- December 28, 1917: The federal government takes control of American railroads in preparation for World War I

- 1923: The Interstate Commerce Commission allows the SP's control of the Central Pacific to continue, ruling that the control is in the public's interest.

- March 1, 1927: Various Texas and Louisiana SP subsidiaries are leased to the SP-controlled Texas and New Orleans Railroad, including the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railway, the Houston and Texas Central Railway, the Houston East and West Texas Railway, the San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railway, and the Southern Pacific Terminal Company.[7][9][10]

- 1928: The SP purchases the Texas Midland Railroad and leases the line to the SP-controlled Texas and New Orleans Railroad.[7][11]

- 1929: Santa Fe sells its interest in Northwestern Pacific to SP. NWP becomes a wholly owned subsidiary of SP.

- 1932: The SP gains 87% control of the Cotton Belt Railroad.

- June 30, 1934: All Texas and Louisiana SP subsidiaries previously leased to the SP-controlled Texas and New Orleans Railroad—with the exception of the Southern Pacific Terminal Company—are formally merged with the T&NO, thus creating the largest railroad in Texas, with 3,713 mi (5,975 km) of track.[7][9]

- May 1939: UP, SP and Santa Fe passenger trains in Los Angeles are united into a single terminal as Los Angeles Union Passenger Terminal opens.

- 1947: The first road diesel locomotives owned solely by SP (i.e., aside from yard switchers) enter operation on the SP.

- 1947: Southern Pacific is reincorporated in Delaware (formerly Kentucky).

- 1951: Southern Pacific subsidiary Southern Pacific of Mexico is sold to the Mexican government.

- 1952: A difficult year for the SP in California opens with the City of San Francisco train marooned for three days in heavy snow on Donner Pass; in July the Kern County earthquake hits Tehachapi pass, closing the line over Tehachapi Loop from 21 July to 15 August.

- 1953: The first Trailer-On-Flat-Car (TOFC, or "piggyback") equipment enters service on the SP.

- January 1957: the last standard gauge steam locomotives in regular operation on the SP are retired; the railroad is now dieselized except for fan excursions.

- 1959: The last revenue steam powered freight is operated on the system by narrow gauge #9.

- 1959: Southern Pacific moved more ton-miles of freight than any other US railroad (the Pennsylvania Railroad had been number one for decades).

- November 1, 1961: The Texas and New Orleans Railroad—which by this time encompassed all of the SP's Texas and Louisiana holdings except for the lines of the Southern Pacific Terminal Company and Cotton Belt—is merged with the Southern Pacific.[7] The SPTC, having been previously leased to the T&NO, is leased to the SP the same day. The SPTC would formally merge with the SP on August 31, 1962.[10]

- 1965: ICC rejects Southern Pacific's bid for control of the Western Pacific.

- 1967: SP opens the longest stretch of new railroad in a quarter century as trains roll over the Palmdale Cutoff through Cajon Pass.

- May 1, 1971: Amtrak takes over long-distance passenger trains in the United States; the only SP revenue passenger trains thereafter were the commutes between San Francisco and San Jose.

- 1972: Southern Pacific Communications began selling surplus capacity on its microwave and fiber optic telecom system (laid along their railroad rights of way) to corporations for use as private lines. This service would evolve into Sprint (the name coming from the acronym for Southern Pacific Railroad Internal Networking Telephony.[1])

- 1976: SP is awarded Dow Chemical's first annual Rail Safety Achievement Award in recognition of the railroad's handling of Dow products in 1975.[12]

- 1980: Now owning a 98.34% control of the Cotton Belt, the Southern Pacific extends the Cotton Belt from St. Louis to Santa Rosa, New Mexico through acquisition of part of the former Rock Island Railroad.

- 1984: Northern portion of subsidiary Northwestern Pacific sold to independent shortline Eureka Southern Railroad which begins operation on November 1.

- 1984: The Southern Pacific Company merges into Santa Fe Industries, parent of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, to form Santa Fe Southern Pacific Corporation. When the Interstate Commerce Commission refuses permission for the planned merger of the railroad subsidiaries as the Southern Pacific Santa Fe Railroad SPSF shortens its name to Santa Fe Pacific Corporation and puts the SP railroad up for sale while retaining the non-rail assets of the Southern Pacific Company.

- 1985: New Caltrain locomotives and rolling stock replace SP equipment on the Peninsula Commute, marking the end of Southern Pacific passenger service with SP equipment.

- August 9, 1988: the Interstate Commerce Commission approves the purchase of the Southern Pacific by Rio Grande Industries, the company that controlled the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad.

- October 13, 1988: Rio Grande Industries takes control of the Southern Pacific Railroad. The merged company retains the name "Southern Pacific" for all railroad operations.

- 1989: Southern Pacific acquires 223 miles of former Alton trackage between St. Louis and Joliet from the Chicago, Missouri & Western. For the first time the Southern Pacific served the Chicago area on its own rails.

- March 17, 1991: The Southern Pacific changes its corporate image, replacing the century-old Roman Lettering with the Rio Grande-inspired Speed Lettering.

- 1992: Northwestern Pacific is merged into SP, ending NWP's existence as a corporate subsidiary of SP[13] and leaving the Cotton Belt as SP's only remaining major railroad subsidiary. The Northwestern Pacific's south end would eventually be sold off by UP and turned into a "new" Northwestern Pacific.

- 1996: The Union Pacific Railroad finishes the acquisition that was effectively begun almost a century before with the purchase of the Southern Pacific by UP in 1901, until divestiture was ordered in 1913. Ironically, although Union Pacific was the dominant company, taking complete control of SP, its corporate structure was merged into Southern Pacific, which on paper became the "surviving company"; which then changed its name to Union Pacific. The merged company retains the name "Union Pacific" for all railroad operations.

| SP | T&NO | SSW | Texas Midland | Dayton-Goose Creek | Lake Tahoe Ry and Transp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1925 | 10,569 | 4,097 | 1,475 | 27 | 15 | 0.05 |

| 1933 | 6,138 | 2,114 | 1,049 | (into T&NO) | (into T&NO) | (into SP) |

| 1944 | 29,877 | 10,429 | 6,243 | |||

| 1960 | 33,280 | 10,192 | 4,750 | |||

| 1970 | 64,988 | (merged SP) | 8,650 |

| SP | T&NO | SSW | Texas Midland | Dayton-Goose Creek | Lake Tahoe Ry and Transp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1925 | 1,580 | 416 | 75 | 2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| 1933 | 869 | 116 | 10 | (into T&NO) | (into T&NO) | (into SP) |

| 1944 | 6,592 | 1,519 | 227 | |||

| 1960 | 1,069 | 128 | 0 | |||

| 1970 | 339 | (merged SP) | 0 |

In the tables "SP" does not include NWP, P&SR, SD&AE, PE, Holton Inter-Urban, Visalia Electric (except 1970 includes PE, which merged into SP in 1965; it reported 104 million ton-miles in 1960). "T&NO" total for 1925 includes GH&SA, H&TC, SA&AP and the other roads that folded into T&NO a couple years later. "SSW" includes SSW of Texas.

1971 Moody's shows route-mileage operated as of 31 December 1970: 11615 SP, 1565 SSW, 324 NWP, 136 SD&AE, 44 T&T, 34 VE, 30 P&SR and 10 HI-U. SP operated 18337 miles of track.

Locomotive paint and appearance

Like most railroads, the SP painted most of its steam locomotives black during the 20th century, but after 1945 SP painted the front of the locomotive's smokebox silver (almost white in appearance), with graphite colored sides, for visibility.

As locomotives are being restored, some pacific type 4-6-2 locomotive boilers show signs of having been painted dark green. The soft cover book "Steam Glory 2" by Kalmbach Publications (2007) has an article "Southern Pacific's Painted Ladies" which shows color photos from the 1940s and 1950s revealing that a number of SP 0-6-0 yard engines, usually assigned to passenger terminals were painted in various combinations with red cab roof and cab doors, pale silver smokeboxes and smokebox fronts, dark green boilers, multi colored SP heralds on black cab, green cylinder covers and other details pointed out in color. Some other SP steam passenger locomotives may have been so painted, or at least had dark green boilers. The article indicates that these paint jobs lasted years and were not special paint for a single event.

Some passenger steam locomotives bore the Daylight scheme, named after the trains they hauled, most of which had the word Daylight in the train name. This scheme, carried on the tender, was a bright red on the top and bottom thirds, with the center third being a bright orange. The parts were separated with narrow silver-gray bands. Some of the color continued along the locomotive. The most famous "Daylight" locomotives were the GS-4 steam locomotives. The most famous Daylight-hauled trains were the Coast Daylight and the Sunset Limited.

Well known were the Southern Pacific's unique "cab-forward" steam locomotives. These were 2-8-8-4 locomotives set up to run in reverse, with the tender attached to the smokebox end of the locomotive. Southern Pacific had a number of snow sheds in mountain terrain, and locomotive crews nearly asphyxiated from smoke in the cab. After a number of engineers began running their engines in reverse (pushing the tender), Southern Pacific asked Baldwin Locomotive Works to produce cab-forward designs. No other North American railroad ordered cab-forward locomotives.

- SP 6051 in the Daylight scheme (2012).

SP 3491 in the Black Widow scheme leads SP 6506 in the Bloody Nose scheme (April 1966).

SP 3491 in the Black Widow scheme leads SP 6506 in the Bloody Nose scheme (April 1966). SP 7561 in the Kodachrome scheme (June 1986).

SP 7561 in the Kodachrome scheme (June 1986).

Early diesel locomotives were also painted black. Yard switchers had diagonal orange stripes on the ends for visibility, earning this scheme the nickname of Tiger Stripe. Road freight units were black with a red band at the bottom of the car body and a silver and orange "winged" nose. "SOUTHERN PACIFIC" was in a large serif font in Lettering Gray (a very light gray). Railfans call this paint scheme Black Widow. An experimental scheme, all-over black with a variety of orange end and side sill treatments was called the Halloween scheme. Over 200 locomotives were so painted between March 1957 and mid-1958.

Most passenger units were painted originally in the Daylight scheme as described above, though some were painted red on top, silver below for the Golden State (operated with the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad) between Chicago and Los Angeles. Silver cars with a narrow red band at the top were used for the Sunset Limited and other trains into Texas. In 1958 SP standardized on a paint scheme of dark grey ("Lark Dark Gray") with a red "winged" nose; railfans dubbed this scheme Bloody Nose. Lettering was again in Lettering Gray.

Anticipating the failed Southern Pacific Santa Fe Railroad merger in the mid 1980s, the "Kodachrome" paint scheme (named for the colors of the Kodak boxes that the film came in) was applied to many Southern Pacific locomotives. When the Southern Pacific Santa Fe merger was denied by the Interstate Commerce Commission, the Kodachrome units were not immediately repainted, some even lasting up to the Southern Pacific's end as an independent company. The Interstate Commerce Commission's decision left Southern Pacific in a decrepit state, the locomotives were not repainted immediately, although some were repainted into the Bloody Nose scheme as they were overhauled after months to years of deferred maintenance.

.jpg) SP 8578 wearing the Bloody Nose scheme with "speed lettering" in 2008.

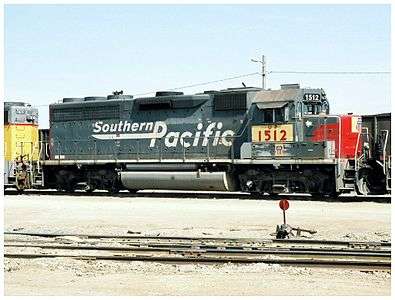

SP 8578 wearing the Bloody Nose scheme with "speed lettering" in 2008. UP 1512 (ex-SP 7134, ex-BO 3706) in Bloody Nose with "speed lettering" and added Union Pacific patches after SP acquisition.

UP 1512 (ex-SP 7134, ex-BO 3706) in Bloody Nose with "speed lettering" and added Union Pacific patches after SP acquisition..jpg) UP 1996 in a Heritage scheme based on Daylight and Black Widow.

UP 1996 in a Heritage scheme based on Daylight and Black Widow.

After the 1988 purchase of Southern Pacific by Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad owner Philip Anschutz, the side lettering on repainted locomotives was changed from SP's serif font to the Rio Grande's "speed lettering" style. The Rio Grande did not retain its identity, as Anschutz felt the Southern Pacific name was the more recognizable. A variation of the Daylight scheme, also known as Popsicles, designed by Chester Mack, was applied to SP's 4 TE-70s, U25Bs repowered with Sulzer diesel engines.[14] Some former SP locomotives largely retained their original Bloody Nose livery, amended with yellow patches and new numbers, following the takeover by Union Pacific.

Southern Pacific road switcher diesels often had elaborate lighting clusters front and rear, with a large red Mars Light for emergency signaling, and often two pairs of sealed-beam headlamps, one on top of the cab and the other below the Mars Light on the nose. Starting in the 1970s SP had cab air conditioning on all new locomotives and the unit is visible on the cab roof. Southern Pacific placed large snowplows on the pilots of their road switchers for the heavy snowfall on Donner Pass. Many Southern Pacific road switchers had a Nathan-AirChime model P3 or P5 air horn with chords distinct to Southern Pacific locomotives in the western states.

The Southern Pacific and Cotton Belt were the only buyers of the EMD SD45T-2 "Tunnel Motor" locomotive. This locomotive was necessary because the standard configuration EMD SD45 could not get a sufficient amount of cool air into the diesel locomotive's radiator while working Southern Pacific's through snow sheds and tunnels in the Cascades and Donner Pass. These "Tunnel Motors" were EMD SD45-2's with radiator air intakes at the locomotive car body's walkway level, rather than EMD's typical setup with fans on the locomotive's long hood roof pulling air through radiators at the top/side of the locomotive's body. Inside tunnels and snow sheds hot exhaust from lead units would accumulate near the top of the tunnel or snow shed and be drawn into the radiators of trailing EMD (non-tunnel motor) locomotives, leading these locomotives to shut down as their diesel prime mover overheated. The Southern Pacific also operated EMD SD40T-2s, as did the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad.

Southern Pacific was known for L-shaped engineer's windshields. Introduced by EMD on SD45 demonstrator 4353, this design improves visibility by omitting the pillar which in conventional designs splits the engineer's windshield into two panes. Southern Pacific selected this option on new EMD locomotive orders starting in 1967 through the early 1980s, one of the few railroads to do so (Illinois Central was another buyer of this option), and ordered a similar windshield design from General Electric. After the "wide nose" design became popular, most of Southern Pacific's locomotives kept their L-shaped windshields before being rebuilt or sold to different private railroads after its merger.

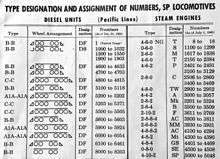

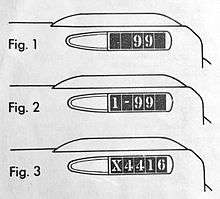

Unlike other railroads whose locomotive number boards bore the locomotive number, SP used them for the train number until 1967. (SP's San Francisco-San Jose commute trains continued displaying train numbers for the convenience of passengers.) The other railroad that used locomotive number boards for train numbers into the 1960s was SP's transcontinental partner, Union Pacific.

On either side of the boiler near the smoke stack or further back, indicators are displayed. These are train numbers (figure 1). All trains going toward San Francisco are called 'westward' and are odd-numbered such as 1, 3, and so on. A train going away from SF are called 'eastward' and are even-numbered. The example in figure 1 shows 99 as the train number which is the number of the streamlined Daylight, northbound.

In order to carry all the people wishing to ride on the same train, sometimes it was necessary to operate the train in two or more separate parts, which are called 'sections.' When a train is operated in sections, the first section carries a '1' preceding the train number (figure 2). The second section carries a '2', etc., and the last section carries the train number only. Special trains or 'extras' carry the locomotive number preceded by an 'X' (figure 3).[15]

In 2006, Union Pacific unveiled UP 1996, the sixth and final of its Heritage Series EMD SD70ACe locomotives. Its paint scheme appears to be based on the Daylight and Black Widow schemes. Today there are still locomotives in SP paint, including ten AC4400CWs with original SP numbers as of January 2013.

Passenger train service

Until May 1, 1971 (when Amtrak took over long-distance passenger operations in the United States), the Southern Pacific at various times operated the following named passenger trains. Trains with names in italicized bold text still operate under Amtrak:

- 49er

- Apache (operated jointly with the Rock Island Railroad 1926–1938)[16]

- Argonaut

- Arizona Limited (operated jointly with the Rock Island Railroad)

- Beaver

- Californian

- Cascade (operates today as part of the Coast Starlight train)

- City of San Francisco (operated jointly with the Chicago and North Western Railway and the Union Pacific Railroad; SP portion operates today as part of Amtrak's California Zephyr)

- Coast Daylight (operates today as part of the Coast Starlight train)

- Coast Mail

- Coaster

- Del Monte

- Fast Mail (Overland Mail)

- Golden Rocket (proposed, was to have been operated jointly with the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad)

- Golden State (operated jointly with the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad)

- Grand Canyon

- Hustler

- Imperial (operated jointly with the Rock Island Railroad 1946–1967)[16]

- Klamath

- Lark

- Oregonian

- Overland

- Owl

- Pacific Limited

- Peninsula Commute (operated until 1985, now Caltrain)

- Rogue River

- Sacramento Daylight

- San Francisco Challenger (operated jointly with the Chicago and North Western Railway and the Union Pacific Railroad)

- San Joaquin Daylight

- Senator

- Shasta Daylight

- Shasta Express[17]

- Shasta Limited

- Shasta Limited De Luxe[17]

- Starlight

- Sunbeam

- Sunset Limited

- Suntan Special

- Tehachapi

- West Coast

- El Costeño (operated from 1927 till 1949 as an international train under the subsidiary Southern Pacific Railroad of Mexico between Tucson, Arizona and Guadalajara in Mexico featuring through sleepers from Los Angeles, California to Mexico City in Mexico)

- El Yaqui (operated from 1927 till 1951 as an international train under the subsidiary Southern Pacific Railroad of Mexico between Tucson, Arizona and Guadalajara in Mexico)

Locomotives Used for Passenger Service

Steam Locomotives

- 2-8-0 Consolidation

- 2-8-2 Mikado

- 4-4-2 Atlantic

- 4-6-2 Pacific – see SP 2472

- 4-8-2 Mountain – see SP Mt-5

- 4-8-4 Golden State/General Service – see SP 4449

- 4-8-8-2 Cab Forward Articulated Mallet

Diesel Locomotives

- ALCO PA

- EMC E2

- EMD E7

- EMD E8

- EMD E9 – see SP 6051

- EMD FP7

- FM H-24-66 "Train Master"

- EMD GP7 – SSW only

- EMD GP9 – see SP 5623

- EMD SD7

- EMD SD9 – see SP 4450

- GE P30CH – leased from Amtrak

- EMD SDP45

- EMD GP40P-2

Notable accidents

- John Sontag, a young Southern Pacific employee, was injured c. 1888 while coupling cars in the railroad yard in Fresno. He accused the company of not providing him with medical care while he was recuperating from his on-the-job injury and then not rehiring him when he had healed. He soon turned to a life of crime, mostly train robberies, and died of gunshot wounds and tetanus in the Fresno jail in 1893 at the age of thirty-two. His partner in crime, Chris Evans, also had a hatred of the Southern Pacific, which he accused of forcing farmers to sell their lands at reduced rates to the company.[18]

- On March 28, 1907, the Southern Pacific Sunset Express, descending the grade out of the San Timoteo Canyon, entered the Colton rail yard traveling about 60 mph, hit an open switch and careened off the track, resulting in twenty-four fatalities. Accounts said all but five of the train's fourteen cars disintegrated as they piled on top of one another, leaving the dead and injured in "a heap of kindling and crumpled metal". Of the dead, eighteen were Italian immigrants traveling to jobs in San Francisco from Genoa, Italy.[19]

- The Coast Line Limited was heading for Los Angeles, California, on May 22, 1907, when it was derailed just west of Glendale, California. Passenger cars reportedly tumbled down the embankment. At least two were killed and others injured. "The horrible deed was planned with devilish accurateness," the Pasadena Star News reported at the time. It said spikes were removed from the track and hook placed under the end of the rail. The Star's coverage was extensive and its editorial blasted the criminal elements behind the wreck. "Diabolism Incarnate" is how they headlined the editorial. It read: "The man or men who committed this horrible deed near Glendale may not be anarchists, technically speaking. But if they are sane men, moved by motive, they are such stuff as anarchists are made of. If the typical anarchist conceived that a railroad corporation should be terrorized, he would not scruple to wreck a passenger train and send scores and hundreds to instant death."

- In the early hours of June 1, 1907, an attempt to derail a Southern Pacific train near Santa Clara, California, was foiled when a pile of railway ties was discovered on the tracks. A work train crew found that someone had driven a steel plate into a switch near Burbank, California, intending to derail the Santa Barbara local.

- On August 12, 1939, the westbound City of San Francisco derailed from a bridge in Palisade Canyon, between Battle Mountain and Carlin in the Nevada desert. Twenty-four passengers and crew members were killed and many more were injured, and five cars were destroyed. An act of sabotage was determined to be the most likely cause; however, no suspect(s) was ever identified.

- On New Year's Eve 1944 a rear end collision west of Ogden in thick fog killed 48 people.

- On January 18, 1947, the Southern Pacific nightflier wrecked 12 miles outside of Bakersfield. 7 people were killed and over 50 injured.Four coaches and a tourist sleeper were overturned, landing far off the tracks. The other seven remained upright. The locomotive stayed on the tracks, and, its crew was uninjured. Robert Crowley, 29, Miami, Fla., a combat war veteran said 'I never saw such a mess," even on a battlefield. He had been conversing with a man across the aisle, Crowley said, and the latter was killed instantly. (Albuquerque Journal January 18, 1947)

- On May 12, 1989, a Southern Pacific train carrying fertilizer material derailed in San Bernardino, California, after descending a nearby slope. The train failed to slow down, and as a result, sped up to about 110 mph before derailing, causing the San Bernardino train disaster. The crash destroyed seven homes along Duffy Street and killed two train workers and two residents. Thirteen days later on May 25, 1989, an underground pipeline running along the right-of-way ruptured and caught fire due to damage done to the pipeline during cleanup from the derailment. Eleven more homes were destroyed and two more people were killed.

- On the night of July 14, 1991, a Southern Pacific train derailed into the upper Sacramento River at a sharp bend of track known as the Cantara Loop, upstream from Dunsmuir, California, in Siskiyou County. Several cars made contact with the water, including a tank car. Early in the morning of 15 July, it became apparent that the tank car had ruptured and spilled its entire contents into the river – approximately 19,000 gallons of a soil fumigant – metam sodium. Ultimately, over a million fish, and tens of thousands of amphibians and crayfish were killed. Millions of aquatic invertebrates, including insects and mollusks, which form the basis of the river's ecosystem, were destroyed. Hundreds of thousands of willows, alders, and cottonwoods eventually died. Many more were severely injured. The chemical plume left a 41-mile wake of destruction, from the spill site to the entry point of the river into Shasta Lake.[20] The accident still ranks as the largest hazardous chemical spill in California history.[21]This substance was not classified as a hazardous material at the time of the incident.

Site of the 1991 spill. The guardrail on the left was constructed after the spill.

Site of the 1991 spill. The guardrail on the left was constructed after the spill.

Preserved locomotives

There are many Southern Pacific locomotives still in revenue service with railroads such as the Union Pacific Railroad, and many older and special locomotives have been donated to parks and museums, or continue operating on scenic or tourist railroads. Most of the engines now in use with Union Pacific have been "patched", where the SP logo on the front is replaced by a Union Pacific shield, and new numbers are applied over the old numbers with a Union Pacific sticker, however some engines remain in Southern Pacific "bloody nose" paint. Among the more notable equipment is:

- Southern Pacific 3100, SP 3100 (former SP6800 Bicentennial) U25B owned and operated by the Orange Empire Railway Museum,[22] Perris, CA

- 4294 (AC-12, 4-8-8-2), located at the California State Railroad Museum, Sacramento, California

- 4449 (GS-4, 4-8-4),formerly located at the Brooklyn Roundhouse before being relocated to the Oregon Rail Heritage Center in June 2012, Portland, Oregon

- 2479 (P-10, 4-6-2), owned and being restored by the California Trolley and Railroad Corporation, San Jose, California

- 2472 (P-8, 4-6-2), owned and operated by the Golden Gate Railroad Museum, Redwood City, California

- 2467 (P-8, 4-6-2), on loan by the Pacific Locomotive Association, Fremont, California to the California State Railroad Museum

- 3420 (C-19, 2-8-0), owned by El Paso Historic Board, stored at Phelps Dodge copper refinery, El Paso, Texas

- 745 (Mk-5, 2-8-2), owned by the Louisiana Rail Heritage Trust, operated by the Louisiana Steam Train Association, and based in Jefferon (near New Orleans), Louisiana

- 4460 (GS-6, 4-8-4), located at the Museum of Transportation, Kirkwood, Missouri

- 1518 (EMD SD7), former EMD demonstrator 990 and first SD7 built, located at the Illinois Railway Museum, Union, Illinois

- 4450 (EMD SD9), located at the Western Pacific Railroad Museum, Portola, California – former commute train engine scrapped in 2013

- 794 (Mk-5, 2-8-2), the last Mikado built for the Texas and New Orleans Railroad in 1916 out of spare parts in their Houston shops. It currently resides with cosmetic restoration at San Antonio Station, San Antonio, Texas, but plans are to restore it to operating condition.

For a complete list, see: List of preserved Southern Pacific Railroad rolling stock.

Morgan Line and the Sunset–Gulf Route

.svg.png)

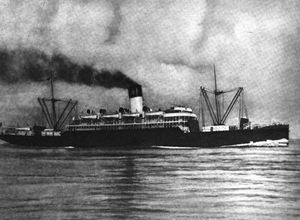

Southern Pacific's Atlantic Steamship Lines, known in operation as the Morgan Line, provided a link between the western rail system through Galveston with freight and New Orleans with both freight and passenger service to New York.[23] In 1915 the New York terminus in the North River included piers 49—52 at the foot of 11th Street.[24]

The steamer service and later operating name began with a small fleet of side wheel steamers owned by Charles Morgan operating out of Gulf ports and later extending to New York. That line was bought by the Morgans, Louisiana & Texas Railroad & Steamship Company that became part of the Southern Pacific system with Pacific Coast to New York service under single management begun February 1, 1883.[23] The Morgan Line, by 1900, had been operating from New Orleans to Cuba for over thirty years and as a result of the war with Spain benefited with the increased trade.[25] Southern Pacific claimed Morgan's blue flag with a white star and red hulled ships were as familiar to Cubans as the lions of Castile as it advertised its new freighters El Norte, El Sud, El Rio as they plied between the company's wharves at Algiers to Havana by way of Key West.[26] By 1899 the company was noting that the railway system, stretching from the Columbia river to the Gulf of Mexico, in conjunction with its steamship lines stretched from New Orleans to New York, Havana and Central American ports and with its Pacific service from San Francisco to Honolulu, Yokohama, Hong Kong and Manila.[27]

In a 1912 report to the United States Senate the Special Commissioner on Panama Traffic and Tolls reported the Southern Pacific's "Sunset—Gulf Route" enabled the line to be the only railroad to control a route between the Atlantic and Pacific Seaboards.[28] The other railroads serving the Pacific Coast largely ran from the Midwest with only one other, the American-Hawaiian Steamship Company competing directly with ships serving Hawaii and the Pacific Coast transshipping cargo and passengers across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec by the Tehuantepec National Railway to meet its ships running to New York.[29] Southern Pacific, using that route under single corporate management, began "active warfare" against its competitors securing a large share of the coast to coast traffic.[29] In 1909 the lines rates were equal to the all rail rates of other railroad lines through a system in which the line absorbed costs getting freight from interior Eastern origins to New York and shipping via the water—rail route that took an average time of fifteen days, five hours.[30]

Five of the line's new ships were among the first six built by the new shipyard at Newport News, Virginia that became Newport News Shipbuilding and the contracts were instrumental in the early success of the company.[31][32] All five, the tug El Toro and the liners El Sol, El Norte, El Sud and El Rio, were taken by the Navy as a Navy tug and as cruisers for the Spanish–American War. The ships were not returned requiring new construction and temporarily crippling the line.[33] Another, El Cid completed in 1893 was sold to Brazil.[31] Ships were leased and in 1899—1901 a new group built including some of the previous name: El Norte, El Dia, El Sud, El Cid, El Rio, El Valle, El Alba, El Siglo and others with a new El Sol built in 1910 along with three others of the same type.[33] Again war took ships, even newly constructed ones such as El Capitan, and the passenger ship Antilles. By 1921 the fleet consisted of five passenger ships, seventeen freighters and two tank ships with more being constructed.[23]

Company officers

Presidents of the Southern Pacific Company

- Timothy Guy Phelps (1865–1868)

- Charles Crocker (1868–1885)

- Leland Stanford (1885–1890)

- Collis P. Huntington (1890–1900)

- Charles Melville Hays (1900–1901)

- E. H. Harriman (1901–1909)

- Robert S. Lovett (1909–1911)

- William Sproule (1911–1918)

- Julius Kruttschnitt (1918–1920)

- William Sproule (1920–1928)

- Paul Shoup (1929–1932)

- Angus Daniel McDonald (1932–1941)

- Armand Mercier (1941–1951)

- Donald J. Russell (1952–1964)

- Benjamin F. Biaggini (1964–1976)

- Denman McNear (1976–1979)

- Alan Furth (1979–1982)

- Robert Krebs (1982–1988)

- D. M. "Mike" Mohan (1988–1993)

- Edward L. Moyers (1993–1995)

- Jerry R. Davis (1995–1996)

Chairmen of the Southern Pacific Company Executive Committee

- Leland Stanford (1890–1893)

- (vacant 1893–1909)

- Robert S. Lovett (1909–1913)

- Julius Kruttschnitt (1913–1925)

- Henry deForest (1925–1928)

- Hale Holden (1928–1932)

Chairmen of the Southern Pacific Company Board of Directors

- Henry deForest (1929–1932)

- Hale Holden (1932–1939)

- (position nonexistent 1939–1964)

- Donald J. Russell (1964–1972)

- Benjamin F. Biaggini (1976–1982)

- Denman K. McNear (1982–1988)

- Edward L. Moyers (1993–1995) Chairman/C.E.O.

Predecessor and subsidiary railroads

Arizona

- Arizona Eastern Railroad 1910–1955

- Arizona Eastern Railroad Company of New Mexico 1904–1910

- Arizona and Colorado Railroad 1902–1910

- Gila Valley, Globe and Northern Railway 1894–1910 later AZER

- Maricopa and Phoenix Railroad (of 1907) 1908–1910

- Maricopa and Phoenix and Salt River Valley Railroad 1895–1908

- Maricopa and Phoenix Railroad (of 1886) 1887–1895

- Arizona Central Railroad 1881–1887

- Phoenix, Tempe and Mesa Railway 1894–1895

- Maricopa and Phoenix Railroad (of 1886) 1887–1895

- Maricopa and Phoenix and Salt River Valley Railroad 1895–1908

- Arizona and Colorado Railroad Company of New Mexico 1904–1910

- El Paso and Southwestern Railroad

- Arizona and New Mexico Railway 1883–1935

- Clifton and Southern Pacific Railway 1883 (Narrow Gauge)

- Clifton and Lordsburg Railway

- Arizona and South Eastern Railroad 1888–1902

- Mexico and Colorado Railroad 1908–1910

- Southwestern Railroad of Arizona 1900–1901

- Southwestern Railroad of New Mexico 1901–1902

- Arizona and New Mexico Railway 1883–1935

- New Mexico and Arizona Railroad 1882–1897 ATSF Subsidiary, 1897–1934 Non-operating SP subsidiary

- Phoenix and Eastern Railroad 1903–1934

- Tucson and Nogales Railroad 1910–1934

- Twin Buttes Railroad 1906–1929; Tucson-Sahuarita line sold to above in 1910. Sahuarita-Twin Buttes line scrapped in 1934.

California

- California Pacific Railroad (Vallejo, California to Sacramento, California)

- Central Pacific Railroad

- Interurban Electric Railway

- Los Angeles & San Pedro Railroad

- Northern Railway

- Northwestern Pacific Railroad

- Oregon and California Railroad

- Pacific Electric Railway

- Sacramento Southern Railroad

- San Diego and Arizona Railway

- San Diego and Arizona Eastern Railway

- San Francisco and San Jose Rail Road

- South Pacific Coast Railroad

- Visalia Electric Railroad

- Western Pacific Railroad (1862-1870) (San Jose, California to Sacramento, California)[34]

- West Side and Mendocino Railroad (Willows, California to Fruto, California)

New Mexico

Oregon

- Oregon and California Railroad 1869–1927

- Oregon Central Railroad 1867–1870

- Portland Traction Company, owned jointly with Union Pacific Railroad and operated independently 1962–1989[35] Portland, Oregon to Oregon City, Oregon and Boring, Oregon

Texas

- Austin and Northwestern Railroad

- Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railway

- Houston East and West Texas Railway

- Houston and Texas Central Railroad

- San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railway, downgraded to secondary status in favor of San Antonio, Uvalde and Gulf Railroad

- Southern Pacific Terminal Company

- Texas Midland Railroad

- Texas and New Orleans Railroad

- El Paso and Northeastern Railway

- El Paso and Southwestern Railroad

Mexico

Successor railroads

Arizona

- Arizona Eastern Railway (AZER) since 1988 from SP

- San Pedro and Southwestern Railroad (SPSR) from SWKR, since 2003

- San Pedro and Southwestern Railway (SWKR) from SP, 1994–2003

Louisiana

- Louisiana and Delta Railroad (LDRR) since 1987

California

- California Northern Railroad

- Eureka Southern Railroad

- Napa Valley Wine Train

- Niles Canyon Railway

- North Coast Railroad

- San Diego and Imperial Valley Railroad

- San Joaquin Valley Railroad

- Big Trees and Pacific Railroad

Oregon

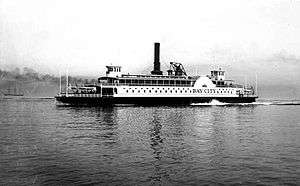

Ferry service

The Central Pacific Railroad (and later the Southern Pacific) maintained and operated a fleet of ferry boats that connected Oakland with San Francisco by water. For this purpose, a massive pier, the Oakland Long Wharf, was built out into San Francisco Bay in the 1870s which served both local and mainline passengers. Early on, the Central Pacific gained control of the existing ferry lines for the purpose of linking the northern rail lines with those from the south and east; during the late 1860s the company purchased nearly every bayside plot in Oakland, creating what author and historian Oscar Lewis described as a "wall around the waterfront" that put the town's fate squarely in the hands of the corporation. Competitors for ferry passengers or dock space were ruthlessly run out of business, and not even stage coach lines could escape the group's notice, or wrath.

By 1930, the Southern Pacific owned the world's largest ferry fleet (which was subsidized by other railroad activities), carrying 40 million passengers and 60 million vehicles annually aboard 43 vessels. The Southern Pacific had also established ferry service across the Mississippi River between Avondale and Harahan, Louisiana[36] and in New Orleans[37] by 1932. However, the opening of the Huey P. Long Bridge in 1935 and the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge in 1936 initiated the slow decline in demand for ferry service, and by 1951 only 6 ships remained active. Mississippi River service ceased by 1953[38][39] and SP ferry service was discontinued altogether in 1958.

Notable employees

- Carl Ingold Jacobson, Los Angeles, California, City Council member, 1925–33

- W. Burch Lee, employee in New Orleans office, along with his father, John Martin Lee, Jr., before serving in the Louisiana House of Representatives[40]

- Charles Wright, Land Surveyor for the railway, before becoming a botanist

See also

- History of rail transportation in California

- Long Wharf (Santa Monica)

- Pacific Fruit Express

- Santa Fe–Southern Pacific merger

- Southern Pacific Depot

- St. Louis Southwestern Railway

References

- 1 2 Block, Melissa; Neff, Brijet (2012-10-15). "Sprint Born From Railroad, Telephone Businesses". NPR. NPR. Archived from the original on 2013-01-14. Retrieved 2013-01-14.

It all began in Kansas in the late 19th century and came to include a long distance system created by the Southern Pacific Railroad Internal Network Telecommunications, or SPRINT.

- 1 2 Blaszak, Michael W. (November 1996). "Southern Pacific: a chronology". Pacific RailNews. Pasadena, California: Interurban Press (396): 25–31.

- ↑ Blaszak, Michael W. "Southern Pacific: a chronology". Interurban Press. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- 1 2 3 Young, Nancy Beck. "Galveston and Red River Railroad". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Werner, George C. "Houston and Texas Central Railway". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- 1 2 Werner, George C. "Buffalo Bayou, Brazos and Colorado Railway". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Williams, Howard C. "Texas and New Orleans Railroad". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ↑ Thomas Samuel Duke. Celebrated Criminal Cases of America. James H. Barry Company, San Francisco, California, 1910. pp. 277–286. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Young, Nancy Beck. "Houston East and West Texas Railway". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 Bart, Joseph L., Jr. "Southern Pacific Terminal Company". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ↑ Reed, S.G. "Texas Midland Railroad". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ↑ <Please add first missing authors to populate metadata.> (August 9, 1976). "Short and Significant: SP wins Dow safety award". Railway Age. Simmons-Boardman Publishing Corporation. 177 (14): 8.

- ↑ Eisen, Jack (April 1994). "NWP disappeared in 1992". Pacific RailNews. Pasadena, California: Interurban Press (365): 48. ISSN 8750-8486. OCLC 11861259.

- ↑ Percy, Richard A. (2007). "Southern Pacific TE70-4S". Espee Railfan. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ↑ Rail Lore, Southern Pacific, 1955

- 1 2 "Imperial and Apache consists". Rock Island Technical Society. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- 1 2 Schwantes, Carlos A. (1993). Railroad Signatures across the Pacific Northwest. University of Washington Press, Seattle, WA. ISBN 0-295-97210-6. OCLC 27266208.

- ↑ "Sontag and Evans". eshomvalley.com. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ↑ San Bernardino Sun, San Bernardino, California, 29 March 1907.

- ↑ Cantara Trustee Council 2007 "Final Report on the Recovery of the Upper Sacramento River"

- ↑ California Department of Toxic Substance Control "20th anniversary of largest chemical spill in California history "http://www.dtsc.ca.gov/cantara.cfm

- ↑ "Orange Empire Railway Museum – Bringing Southern California's Railway History to Life.".

- 1 2 3 Luce, G. W. (1920). "Sunset Gulf—The 100 Per Cent Route". Southern Pacific Bulletin. San Francisco: Southern Pacific. 10 (February 1921): 16–18. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ↑ Rand McNally (1915). Rand McNally Hudson River Guide. New York, Chicago: Rand McNally & Company. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ↑ Mayo 1900, p. 96.

- ↑ Mayo 1900, pp. 96—98.

- ↑ Woodman (Editor) 1899, p. 100.

- ↑ Johnson 1912, p. 4.

- 1 2 Johnson 1912, p. 8.

- ↑ Johnson 1912, p. 22.

- 1 2 ShipbuildingHistory: Newport News Shipbuilding.

- ↑ Beale 1907, p. 56.

- 1 2 Jungen 1922, p. 5.

- ↑ Not the Gould Western Pacific of 1903

- ↑ "The Rise and Fall of the Portland Traction Company". Craigsrailroadpages.com. Retrieved 2012-05-15.

- ↑ "Map of the Avondale/Harahan area in 1932". Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ "Map of New Orleans in 1932". Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ "Map of the Avondale/Harahan area in 1953". Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ "Map of New Orleans in 1953". Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ "W. Burch Lee Funeral Here in Afternoon: Former Clerk of Federal Court Expires After Week of Illness". The Shreveport Times through findagrave.com. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- General

- Beale, Edwin I. (1907). Highways & Byways of the Virginia Peninsula. Newport News, Virginia: E. I. Beale. LCCN 07009602.

- Beebe, Lucius (1963). The Central Pacific and The Southern Pacific Railroads. Berkeley, California: Howell-North Books. ISBN 0-8310-7034-X.

- Colton, T. (May 2, 2014). "Newport News Shipbuilding, Newport News VA". ShipbuildingHistory. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- Cooper, Bruce C. (2005). Riding the Transcontinental Rails: Overland Travel on the Pacific Railroad 1865–1881. Philadelphia: Polyglot Press. ISBN 1-4115-9993-4.

- Cooper, Bruce Clement, ed. (2010). The Classic Western American Railroad Routes. New York: Chartwell Books/Worth Press. ISBN 978-0-7858-2573-9. BINC: 3099794.

- Daggett, Stuart. Chapters on the History of the Southern Pacific (1922) online. detailed history

- Darton, D. H. (1933). Guidebook of the Western United States; Part F. The Southern Pacific Lines, New Orleans to Los Angeles. Geological Survey Bulletin 845. Washington (D.C.): Government Printing Office.

- Darton, D.H. Guidebook of the Western United States; Part F. The Southern Pacific Lines, New Orleans to Los Angeles. Geological Survey Bulletin 845. Washington (D.C.): Government Printing Office, 1933.

- Diebert, Timothy S. & Strapac, Joseph A. (1987). Southern Pacific Company steam locomotive compendium. Huntington Beach, California: Shade Tree Books. ISBN 0-930742-12-5. OCLC 18401969.

- Hofsommer, Donovan; The Southern Pacific, 1901–1985. Texas A&M University Press; (1986) ISBN 9781603441278.

- Johnson, Emory R. (1912). The Relation of the Panama Canal to the Traffic and Rates of American Railroads. United States Senate Reports. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- Jungen, C. W. (1922). "Ocean Unit of Lines That Span Continent". Southern Pacific Bulletin. San Francisco: Southern Pacific. 11 (January 1922). Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- Lewis, Daniel (2007). Iron Horse Imperialism: The Southern Pacific of Mexico, 1880–1951. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-2604-4. OCLC 238833401.

- Mayo, H. M. (1900). "Cuba and the Way There". Sunset. San Francisco: Passenger Department Southern Pacific Company. 4 (January, 1900): 95–98. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- Lewis, Oscar (1938). The Big Four. New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- Orsi, Richard J. (2005). Sunset Limited: The Southern Pacific Railroad and the Development of the American West 1850–1930. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20019-5. OCLC 55055386.

- Thompson, Anthony W. (1992). Pacific Fruit Express. Wilton, California: Signature Press. ISBN 1-930013-03-5. OCLC 48551573.

- Woodman (Editor), E. H. (1899). "Transportation". Sunset. San Francisco: Passenger Department Southern Pacific Company. 2 (March, 1899). Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- Yenne, Bill (1985). The History of the Southern Pacific. New York, New York: Bonanza. ISBN 0-517-46084-X. OCLC 11812708.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Southern Pacific Transportation Company. |

- Sphts.org: Southern Pacific Historical & Technical Society

- Harvard Business School, Lehman Brothers Collection: "History of the Southern Pacific Transportation Company"

- Peter J. McClosky's Southern Pacific Railroad Web Resources Page

- Coscis-espee.info: David Coscia's Southern Pacific Site

- Espee.railfan.net: Southern Pacific Passenger Train Consists

- Union Pacific Railroad.com: Union Pacific History

- "Across the Great Salt Lake, The Lucin Cutoff" — 1937 article.

- Los Angeles River Railroads

- Abandoned Rails.com: History of the Santa Ana and Newport Railroad.