Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands

Southeastern Woodlands peoples, Southeastern cultures, or Southeast Indians are an ethnographic classification for Indigenous peoples that have traditionally inhabited the Southeastern United States and the northeastern border of Mexico, that share common cultural traits.

The area was linguistically diverse, major language groups were Caddoan and Muskogean, besides a number of language isolates.

Cultural region

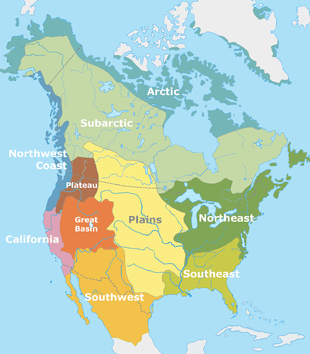

This classification is a part of the Eastern Woodlands. The concept of a southeastern cultural region was developed by anthropologists, beginning with Otis Mason and Frank Boas in 1887. The boundaries of the region are defined more by shared cultural traits than by geographic distinctions.[1] Because the cultures gradually instead of abruptly shift into Plains, Prairie, or Northeastern Woodlands cultures, scholars do not always agree on the exact limits of the Southeastern Woodland culture region. Shawnee, Powhatan, Waco, Tawakoni, Tonkawa, Karankawa, Quapaw, and Mosopelea are usually seen as marginally southeastern and their traditional lands represent the borders of the cultural region.[2]

Culture and history

The following section deals primarily not with the culture of the peoples in the lengthy period before European contact. Evidence of the preceding cultures have been found primarily in archeological artifacts, but also in major earthworks and the evidence of linguistics. In the Late Prehistoric time period in the Southeastern Woodlands, cultures increased agricultural production, developed ranked societies, increased their populations, trade networks, and intertribal warfare.[3] Most Southeastern peoples (excepting some of the coastal peoples) were highly agricultural, growing crops like maize, squash, and beans for food. They supplemented their diet with hunting, fishing,[4] and gathering wild plants and fungi.

Frank Speck identified several key cultural traits of Southeastern Woodlands peoples. Social traits included having a matrilineal kinship system, exogamous marriage between clans, and organizing into settled villages and towns.[1] Southeastern Woodlands societies were usually divided into clans; the most common from pre-contact Hopewellian times into the present include Bear, Beaver, Bird other than a raptor, Canine (e.g. Wolf), Elk, Feline (e.g. Panther), Fox, Raccoon, and Raptor.[5] They observe strict incest taboos, including taboos against marriage within a clan. In the past, they frequently allowed polygamy to chiefs and other men who could support multiple wives. They held puberty rites for both boys and girls.[4]

Southeastern peoples also traditionally shared similar religious beliefs, based on animism. They used fish poison, and practiced purification ceremonies among their religious rituals, as well as the Green Corn Ceremony.[1] Medicine people are important spiritual healers.

Many southeastern peoples engaged in mound building to create sacred or acknowledged ritual sites. Many of the religious beliefs of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex or the Southern Cult, were also shared by the Northeastern Woodlands tribes, probably spread through the dominance of the Mississippian culture in the 10th century.

Post-European contact

During the Indian Removal era of the 1830s, most southeastern tribes were forcibly relocated to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River by the US federal government, as European-American settlers pushed the government to acquire their lands.[6] Some members of the tribes chose to stay in their homelands and accept state and US citizenship; others simply hid in the mountains or swamps and sought to maintain some cultural continuity. Since the late 20th century, descendants of these people have organized as tribes; in a limited number of cases, some have achieved federal recognition but more have gained state recognition through legislation at the state level.

Visual arts

Belonging in the Lithic stage, the oldest known art in the Americas is the Vero Beach bone found in present-day Florida. It is possibly a mammoth bone, etched with a profile of walking mammoth; it dates to 11,000 BCE.[7]

The Poverty Point culture inhabited portions of the state of Louisiana from 2000–1000 BCE during the Archaic period.[8] Many objects excavated at Poverty Point sites were made of materials that originated in distant places, indicating that the people were part of an extensive trading culture. Such items include chipped stone projectile points and tools; ground stone plummets, gorgets and vessels; and shell and stone beads. Stone tools found at Poverty Point were made from raw materials that can be traced to the relatively nearby Ouachita and Ozark mountains, as well as others from the more distant Ohio and Tennessee River valleys. Vessels were made from soapstone which came from the Appalachian foothills of Alabama and Georgia.[9] Hand-modeled lowly fired clay objects occur in a variety of shapes including anthropomophic figurines and cooking balls.[8]

"Poverty point objects," earthenware, believe to be for cooking, Poverty Point

Clay female figurines, Poverty Point

Carved shell gorgets and atlatl weights, Poverty Point

The Calusa peoples, of southern Florida, carved and painted wood in exquisite depictions of animals.

Mississippian cultures flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 CE to 1500 CE, varying regionally.[10] After adopting maize agriculture the Mississippian culture became fully agrarian, as opposed to the preceding Woodland cultures that supplemented hunting and gathering with limited horticulture. Mississippian peoples often built platform mounds. They refined their ceramic techniques and often used ground mussel shell as a tempering agent. Many were involved with the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, a multi-regional and multi-linguistic religious and trade network that marked the southeastern part of the Mississippian Ideological Interaction Sphere. Information about Southeastern Ceremonial Complex primary comes from archaeology and the study of the elaborate artworks left behind by its participants, including elaborate pottery, conch shell gorgets and cups, stone statuary, and Long-nosed god maskettes.

By the time of European contact the Mississippian societies were already experiencing severe social stress. Some major centers had already been abandoned.With social upsets and diseases introduced by Europeans many of the societies collapsed and ceased to practice a Mississippian lifestyle, with an exception being the Natchez people of Mississippi and Louisiana. Other tribes descended from Mississippian cultures include the Alabama, Biloxi, Caddo, Choctaw, Muscogee Creek, Tunica, and many other southeastern peoples.

Engraved shell gorget, Spiro Mounds, Oklahoma (Mississippian culture)

Ceremonial stone mace, Spiro Mounds, Oklahoma (Mississippian culture)

Engraved stone palette, Moundville Site, Alabama, back used for mixing paint (Mississippian culture)

Stone effigy pipe, Spiro Mounds (Mississippian culture)

Stone effigies, Etowah Site, Georgia (Mississippian culture)

Alligator effigy, wood carving, Calusa, Florida

List of indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands

- Acolapissa (Colapissa), Louisiana and Mississippi[11]

- Ais, eastern coastal Florida[12]

- Alafay (Alafia, Pojoy, Pohoy, Costas Alafeyes, Alafaya Costas), Florida[13]

- Amacano, Florida west coast[14]

- Apalachee, northwestern Florida[15]

- Atakapa (Attacapa), Louisiana west coast and Texas southwestern coast[15]

- Avoyel ("little Natchez"), Louisiana[11][17]

- Bayogoula, southeastern Louisiana[11][17]

- Biloxi, Mississippi[11][15]

- Caddo Confederacy, Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas[15][18]

- Adai (Adaizan, Adaizi, Adaise, Adahi, Adaes, Adees, Atayos), Louisiana and Texas[11]

- Cahinnio, southern Arkansas[18]

- Doustioni, north central Louisiana[18]

- Eyeish (Hais), eastern Texas[18]

- Hainai, eastern Texas[18]

- Hasinai, eastern Texas[18]

- Kadohadacho, northeastern Texas, southwestern Arkansas, northwestern Louisiana[18]

- Nabedache, eastern Texas[18]

- Nabiti, eastern Texas[18]

- Nacogdoche, eastern Texas[18]

- Nacono, eastern Texas[18]

- Nadaco, eastern Texas[18]

- Nanatsoho, northeastern Texas[18]

- Nasoni, eastern Texas[18]

- Natchitoches, Lower: central Louisiana, Upper: northeastern Texas[18]

- Neche, eastern Texas[18]

- Nechaui, eastern Texas[18]

- Ouachita, northern Louisiana[18]

- Tula, western Arkansas[18]

- Yatasi, northwestern Louisiana[18]

- Calusa, southwestern Florida[13][15]

- Cape Fear Indians, North Carolina southern coast[11]

- Catawba (Esaw, Usheree, Ushery, Yssa),[19] North Carolina, South Carolina[15]

- Chacato, Florida panhandle and southern Alabama[11]

- Chakchiuma, Alabama and Mississippi[15]

- Chatot people (Chacato, Chactoo), west Florida

- Chawasha (Washa), Louisiana[11]

- Cheraw (Chara, Charàh), North Carolina

- Cherokee, western North Carolina, eastern Tennessee, later Georgia, northwestern South Carolina, northern Alabama, Arkansas, Texas, Mexico, and currently North Carolina and Oklahoma[20]

- Chickanee (Chiquini), North Carolina

- Chickasaw, Alabama and Mississippi,[15] later Oklahoma[20]

- Chicora, coastal South Carolina[17]

- Chine, Florida

- Chisca (Cisca), southwestern Virginia, northern Florida[17]

- Chitimacha, Louisiana[15]

- Choctaw, Mississippi, Alabama,[15] and parts of Louisiana; later Oklahoma[20]

- Chowanoc (Chowanoke), North Carolina

- Coharie, North Carolina

- Congaree (Canggaree), South Carolina[11][21]

- Coree, North Carolina[17]

- Coharie, North Carolina

- Croatan, North Carolina

- Cusabo coastal South Carolina[15]

- Eno, North Carolina[11]

- Grigra (Gris), Mississippi[22]

- Guacata (Santalûces), eastern coastal Florida[13]

- Guacozo, Florida

- Guale (Cusabo, Iguaja, Ybaja), coastal Georgia[11][15]

- Guazoco, southwestern Florida coast[13]

- Houma, Louisiana and Mississippi[15]

- Jaega (Jobe), eastern coastal Florida[12]

- Jaupin (Weapemoc), North Carolina

- Jororo, Florida interior[13]

- Keyauwee, North Carolina[11]

- Koasati (Coushatta), formerly eastern Tennessee,[15] currently Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas

- Koroa, Mississippi[11]

- Luca, southwestern Florida coast[13]

- Lumbee, North Carolina

- Machapunga, North Carolina

- Matecumbe (Matacumbêses, Matacumbe, Matacombe), Florida Keys[13]

- Mayaca, Florida[13]

- Mayaimi (Mayami), interior Florida[12]

- Mayajuaca, Florida

- Mikasuki (Miccosukee), Florida

- Mobila (Mobile, Movila), northwestern Florida and southern Alabama[15]

- Mocoso, western Florida[12][13]

- Mougoulacha, Mississippi[17]

- Muscogee (Creek), Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, later Oklahoma

- Abihka, Alabama,[16] later Oklahoma

- Alabama, formerly Alabama,[16] southwestern Tennessee, and northwestern Mississippi,[11][15] now Oklahoma and Texas

- Apalachicola, Creek Confederacy, Alabama, Florida, Georgia and South Carolina[16]

- Chiaha, Creek Confederacy, Alabama[16]

- Eufaula tribe, Georgia, later Oklahoma

- Hitchiti, Creek Confederacy, Georgia, Alabama, and Florida[11]

- Oconee, Georgia, Florida

- Kialegee Tribal Town, Alabama, later Oklahoma

- Osochee (Osochi, Oswichee, Usachi, Oosécha), Creek Confederacy, Alabama[11][16]

- Talapoosa, Creek Confederacy, Alabama[16]

- Thlopthlocco Tribal Town, Alabama, Georgia, later Oklahoma

- Tukabatchee, Muscogee Creek Confederacy, Alabama[16]

- Naniaba, northwestern Florida and southern Alabama[15]

- Natchez, Louisiana and Mississippi[15] later Oklahoma

- Neusiok (Newasiwac, Neuse River Indians), North Carolina[11]

- Norwood culture, Apalachee region, Florida, c. 12,000 BCE — 4500 BCE

- Ofo, (Mosopelea), Arkansas and Mississippi,[15] eastern Tennessee[11]

- Okchai (Ogchay), central Alabama[11]

- Okelousa, Louisiana[11]

- Opelousas, Louisiana[11]

- Pacara, Florida

- Pamlico, formerly North Carolina

- Pascagoula, Mississippi coast[17]

- Pee Dee (Pedee), South Carolina[11][23] and North Carolina

- Pensacola, Florida panhandle and southern Alabama[15]

- Potoskeet, North Carolina

- Quinipissa, southeastern Louisiana and Mississippi[16]

- Roanoke, North Carolina

- Saluda (Saludee, Saruti), South Carolina[11]

- Santee (Seretee, Sarati, Sati, Sattees), South Carolina (no relation to Santee Sioux), South Carolina[11]

- Santa Luces, Florida

- Saponi, North Carolina,[24] Virginia[25]

- Saura, North Carolina

- Sawokli (Sawakola, Sabacola, Sabacôla, Savacola), southern Alabama and Florida panhandle[11]

- Saxapahaw (Sissipahua, Shacioes), North Carolina[11]

- Secotan, North Carolina

- Seminole, Florida and Oklahoma[20]

- Sewee (Suye, Joye, Xoye, Soya), South Carolina coast[11]

- Shakori, North Carolina

- Shoccoree (Haw), North Carolina,[11] possibly Virginia

- Sissipahaw, North Carolina

- Sugeree (Sagarees, Sugaws, Sugar, Succa), North Carolina and South Carolina[11]

- Surruque, east central Florida[26]

- Suteree (Sitteree, Sutarees, Sataree), North Carolina

- Taensa, Mississippi[22]

- Tawasa, Alabama[27]

- Tequesta, southeastern coastal Florida[11][13]

- Timucua, Florida and Georgia[11][13][15]

- Acuera, central Florida[28]

- Agua Fresca (or Agua Dulce or Freshwater), interior northeast Florida[28]

- Arapaha, north central Florida and south central Georgia?[28]

- Cascangue, coastal southeast Georgia[28]

- Icafui (or Icafi), coastal southeast Georgia[28]

- Mocama (or Tacatacuru), coastal northeast Florida and coastal southeast Georgia[28]

- Northern Utina north central Florida[28]

- Ocale, central Florida[28]

- Oconi, interior southeast Georgia[28]

- Potano, north central Florida[28]

- Saturiwa, northeast Florida[28]

- Tacatacuru, coastal southeast Georgia[29]

- Tucururu (or Tucuru), central? Florida[28]

- Utina (or Eastern Utina), northeast central Florida[30]

- Yufera, coastal southeast Georgia[28]

- Yui (Ibi), coastal southeast Georgia[28]

- Yustaga, north central Florida[28]

- Tiou (Tioux), Mississippi[21]

- Tocaste, Florida[13]

- Tocobaga, Florida[11][13]

- Tohomé, northwestern Florida and southern Alabama[15]

- Tomahitan, eastern Tennessee

- Topachula, Florida

- Tunica, Arkansas and Mississippi[15]

- Utiza, Florida[12]

- Uzita, Tampa Bay, Florida[31]

- Vicela, Florida[12]

- Viscaynos, Florida

- Waccamaw, South Carolina

- Waccamaw Siouan, North Carolina

- Wateree (Guatari, Watterees), North Carolina[11]

- Waxhaw (Waxsaws, Wisack, Wisacky, Weesock, Flathead), North Carolina and South Carolina[11][23]

- Westo, Virginia and South Carolina,[17] extinct

- Winyaw, South Carolina coast[11]

- Woccon, North Carolina[11][23]

- Yamasee, Florida, Georgia[17]

- Yazoo, southeastern tip of Arkansas, eastern Louisiana, Mississippi[11][32]

- Yuchi (Euchee), central Tennessee,[11][15] then northwest Georgia, now Oklahoma

Contemporary federally recognized Southeastern Woodlands tribes

- Alabama-Coushatta Tribes of Texas

- Alabama-Quassarte Tribal Town, Oklahoma

- Caddo Nation of Oklahoma

- Catawba Indian Nation, South Carolina

- Cherokee Nation, Oklahoma

- Chickasaw Nation, Oklahoma

- Chitimacha Tribe of Louisiana

- Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma

- Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana

- Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians of North Carolina

- Jena Band of Choctaw Indians, Louisiana

- Kialegee Tribal Town, Oklahoma

- Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida

- Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, Mississippi

- Muscogee (Creek) Nation, Oklahoma

- Poarch Band of Creek Indians of Alabama

- Seminole Tribe of Florida

- Thlopthlocco Tribal Town, Oklahoma

- Tunica-Biloxi Indian Tribe of Louisiana

- United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma

See also

- Classification of indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Indigenous peoples of Florida

- Northeastern Woodlands tribes

- Stomp dance

- Trail of Tears

Notes

- 1 2 3 Jackson and Fogelson 3

- ↑ Jackson and Fogelson 6

- ↑ Messenger, Lewis C. "The Southeastern Woodlands: Mississippian-Late Prehistoric Cultural Developments." citation needed] University of Indiana: MATRIX. (retrieved 2 June 2011)

- 1 2 "Southeastern Woodlands Culture." Four Directions Institute. (retrieved 2 June 2011)

- ↑ Carr and Case 340

- ↑ "People and Events: Indian Removal, 1814-1858." PBS: Resource Bank. (retrieved 25 April 2010)

- ↑ "Ice Age Art from Florida." Past Horizons, 23 June 2011 (retrieved 23 June 2011)

- 1 2 "Poverty Point-2000 to 1000 BCE". Retrieved 2009-03-02.

- ↑ "CRT-Louisiana State Parks Fees, Facilities and Activities". Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-02.

- ↑ Mississippian Period: Overview

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 Sturtevant and Fogelson, 69

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sturtevant and Fogelson, 205

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Sturtevant and Fogelson, 214

- ↑ Sturtevant and Fogelson, 673

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Sturtevant and Fogelson, ix

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Sturtevant and Fogelson, 374

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Sturtevant and Fogelson, 81-82

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Sturtevant, 617

- ↑ Folgelson, ed. (2004), p. 315

- 1 2 3 4 Frank, Andrew K. Indian Removal. Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- 1 2 Sturtevant and Fogelson, 188

- 1 2 Sturtevant and Fogelson, 598-9

- 1 2 3 Sturtevant and Fogelson, 302

- ↑ Haliwa-Saponi Tribe. . Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- ↑ Sturtevant and Fogelson 293

- ↑ Hann 1993

- ↑ Sturtevant and Fogelson, 78, 668

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Hann 1996, 5-13

- ↑ Milanich 1999, p. 49.

- ↑ Milanich 1996, p. 46.

- ↑ Hann 2003:11

- ↑ Sturtevant and Fogelson, 190

References

- Carr, Christopher and D. Troy Case. Gathering Hopewell: Society, Ritual, and Ritual Interaction. New York: Springer, 2006. ISBN 978-0-306-48479-7.

- Hann, John H. "The Mayaca and Jororo and Missions to Them", in McEwan, Bonnie G. ed. The Spanish Missions of "La Florida". Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. 1993. ISBN 0-8130-1232-5.

- Hann, John H. A History of the Timucua Indians and Missions. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida, 1996. ISBN 0-8130-1424-7.

- Hann, John H. (2003). Indians of Central and South Florida: 1513-1763. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2645-8

- Jackson, Jason Baird and Raymond D. Fogelson. "Introduction." Sturtevant, William C., general editor and Raymond D. Fogelson, volume editor. Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast. Volume 14. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2004: 1-68. ISBN 0-16-072300-0.

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- Sturtevant, William C., general editor and Raymond D. Fogelson, volume editor. Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast. Volume 14. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2004. ISBN 0-16-072300-0.

- Roark, Elisabeth Louise. Artists of Colonial America. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2003. ISBN 978-0-313-32023-1.