South Street Seaport

|

South Street Seaport | |

|

South Street and Brooklyn Bridge (c.1900) | |

| |

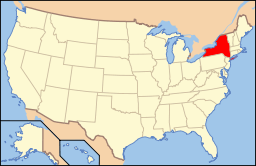

| Location | Bounded by Burling (John St.) and Peck Slips, Water St. and East River in New York City, United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | Coordinates: 40°42′22″N 74°0′12″W / 40.70611°N 74.00333°W |

| Area | 3.5 acres (1.4 ha) |

| Architect | multiple |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival |

| NRHP Reference # | |

|

South Street Seaport Historic District | |

| Location | Roughly bounded by East River, Brooklyn Bridge, Fletcher Alley, and Pearl and South Streets, Manhattan, New York City, United States |

| Area | 41 acres (17 ha) |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival, Romanesque |

| NRHP Reference # | 78001884[1] |

| Added to NRHP | December 12, 1978 |

| Added to NRHP | October 18, 1972 |

The South Street Seaport is a historic area in the New York City borough of Manhattan, centered where Fulton Street meets the East River, and adjacent to the Financial District. The Seaport is a designated historic district, and is distinct from the neighboring Financial District. It is part of Manhattan Community Board 1 in Lower Manhattan, and is bounded by the Financial District to the west, southwest, and north; the East River to the southeast; and Two Bridges to the northeast.

It features some of the oldest architecture in downtown Manhattan, and includes the largest concentration of restored early 19th-century commercial buildings in the city. This includes renovated original mercantile buildings, renovated sailing ships, the former Fulton Fish Market, and modern tourist malls featuring food, shopping, and nightlife, with a view of the Brooklyn Bridge.

History

As port

The first pier in the area appeared in 1625, when the Dutch West India Company founded an outpost here.[2] With the influx of the first settlers, the area was quickly developed. One of the first and busiest streets in the area was today's Pearl Street, so named for a variety of coastal pearl shells.[3] Due to its location, Pearl Street quickly gained popularity among traders.[4][5] The East River was eventually narrowed. By the second half of the 17th century, the pier was extended to Water Street, then to Front Street, and by the beginning of the 19th century, to South Street.[2] The pier was well reputed, as it was protected from westerly winds and ice of the Hudson River.[3]

In 1728, the Schermerhorn Family established trade with the city of Charleston, South Carolina. Subsequently, rice and indigo came from Charleston.[6] At the time, the port was also the focal point of delivery of goods from England. In 1776, during the American Revolutionary War, the British occupied the port, adversely affecting port trade for eight years. In 1783, many traders returned to England, and most port enterprises collapsed.[2] The port quickly recovered from the post-war crisis. From 1797 until the middle of 19th century, New York had the country's largest system of maritime trade.[2] From 1815 to 1860 the port was called the Port of New York.

On February 22, 1784, the Empress of China sailed from the port to Guangzhou and returned to Philadelphia on May 15, 1785,[7] bringing along, in its cargo, green and black teas, porcelain, and other goods.[8] This operation marked the beginning of trade relations between the newly formed United States and the Qing Empire.[9]

On January 5, 1818, the 424-ton transatlantic packet James Monroe sailed from Liverpool, opening the first regular trans-Atlantic voyage route, the Black Ball Line.[10] Shipping on this route continued until 1878.[11] Commercially successful transatlantic traffic has led to the creation of many competing companies, including the Red Star Line in 1822.[12][13] Transportation significantly contributed to the establishment of the New York one of the centers of world trade.[2]

.jpg)

One of the largest companies in the South Street Seaport area was the Fulton Fish Market, opened in 1822. In 2005, it was moved to the area of Hunts Point, Bronx.[14][15]

In November 1825, the Erie Canal, located upstate, was opened.[16] The canal, connecting New York to the western United States, facilitated the economic development of the city.[17][18] However, for this reason, along with the beginning of the shipping era, there was a need to lengthen the piers and deepen the port.[19]

On the night of December 17, 1835 a large fire in New York City destroyed 17 blocks,[20] and many buildings in the South Street Seaport burned to the ground. Nevertheless, by the 1840s, the port recovered, and by 1850, it reached its heyday:[2]

Looking east, was seen in the distance on the long river front from Coenties Slip to Catharine Street [sic], innumerable masts of the many Californian clippers and London and Liverpool packets, with their long bowsprits extending way over South Street, reaching nearly to the opposite side.[21]

At its peak, the port hosted many commercial enterprises, institutions, ship-chandlers, workshops, boarding houses, saloons, and brothels. However, by the 1880s, the port began to be depleted of resources, space for the development of these businesses was diminishing, and the port became too shallow for newer ships. By the 1930s, most of the piers no longer functioned, and cargo ships docked mainly on ports on the West Side and in Hoboken.[3] By the late 1950s, the old Ward Line docks, comprising Piers 15, 16, and part of 17, were mostly vacant.

As museum

The South Street Seaport Museum was founded in 1967 by Peter and Norma Stanford. When originally opened as a museum, the focus of the Seaport Museum conservation was to be an educational historic site, with shops mostly operating as reproductions of working environments found during the Seaport's heyday.

In 1982, redevelopment began to turn the museum into a greater tourist attraction via development of modern shopping areas. The project was undertaken by the prominent developer James Rouse and modeled on the concept of a "festival marketplace," a leading revitalization strategy throughout the 1970s.[22] On the other side of Fulton Street from Schermerhorn Row, the main Fulton Fish Market building, which had become a large plain garage-type structure, was rebuilt as an upscale shopping mall. Pier 17's old platforms were demolished and a new glass shopping pavilion raised in its place, which opened in August 1983.

The original intent of the Seaport development was the preservation of the block of buildings known as Schermerhorn Row on the southwest side of Fulton Street, which were threatened with neglect or future development, at a time when the history of New York City's sailing ship industry was not valued, except by some antiquarians. Early historic preservation efforts focused on these buildings and the acquisition of several sailing ships. Almost all buildings and the entire Seaport neighborhood are meant to transport the visitor back in time to New York's mid-19th century, to demonstrate what life in the commercial maritime trade was like. Docked at the Seaport are a few historical sailing vessels, including the Wavertree. A section of nearby Fulton Street is preserved as cobblestone and lined with shops, bars, and restaurants. The Bridge Cafe, which claims to be "The Oldest Drinking Establishment in New York" is in a building that formerly housed a brothel.

In 2012, Hurricane Sandy heavily damaged the Seaport; tidal floods (seven feet deep in places) inundated much of the Seaport causing extensive damage that forced an end to plans to restore the Museum's fortunes by merging it into the Museum of the City of New York.[23] Many of the businesses closed, and the remaining businesses suffered from a severe drop in business after the storm. The South Street Seaport Museum re-opened in December 2012. The Howard Hughes Corporation, the Seaport's owner, announced that it would tear down the Seaport's most prominent shopping area, Pier 17, starting in the fall of 2013, and will replace it with a new structure by 2015.[24][25]

Ownership and management

The Seaport is currently owned and managed by the Howard Hughes Corporation. Formerly, it was run by General Growth Properties, who acquired the Seaport's longtime owner, the Rouse Company, in 2004.[26] As part of its restructuring, General Growth spun off the Howard Hughes Corporation.[27]

Constituent parts

Museum

Designated by Congress in 1998 as one of several museums which together make up "America's National Maritime Museum", South Street Seaport Museum sits in a 12 square-block historic district that is the site of the original port of New York City.[28] The Museum has over 30,000 square feet (2,800 m2) of exhibition space and educational facilities. It houses exhibition galleries, a working 19th-century print shop, an archeology museum, a maritime library, a craft center, a marine life conservation lab, and the largest privately owned fleet of historic ships in the country.

Shopping mall and tourist attraction

At the Seaport a mall and tourism center, is built on Pier 17 on the East River. Visitors may choose from among many shops and a food court. Currently, Pier 17 is closed and is scheduled to reopen at either the end of 2016/ beginning of 2017.[29] However, there are other dining and clothing boutiques opened in the area worth checking out.[30] Decks outside on pier 15[31] allow views of the East River, Brooklyn Bridge, and Brooklyn Heights.

At the entrance to the Seaport is the Titanic Memorial lighthouse.

Ships in the port

The museum has five vessels docked permanently or semi-permanently, four of which have formal historical status.

| Name | Year of launch | Type | Description | Picture | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States Lightship LV-87 | 1908 | Lightship | LV-87 is a lightship 135 feet (41 m) long and 29 feet (8.8 m) wide, built in Camden, New Jersey in 1907. It was stationed at the entrance to Ambrose Channel and became the third lightship there since 1854. In 1932 the ship was replaced by the new LV-111 ship and moved to the Scotland Station. LV-87 was retired in 1966 and sent to the South Street Seaport in 1968. In 1989 it gained National Historic Landmark status. |  |

[32][33][34][35][36][37][38] |

| Lettie G. Howard | 1893 | Schooner | The fishing schooner was launched in Essex, Massachusetts. The vessel is 125 feet (38 m) long overall and 21 feet (6.4 m) wide. The schooner was used for fishing mostly off the coast of Yucatan. In 1989 it was given National Historic Landmark status. |  |

[39][40][41][42] |

| Pioneer | 1885 | Schooner | The schooner was launched in Marcus Hook, Pennsylvania in Pennsylvania. Initially, it was rigged as a sloop, but in 1895 it was rerigged as a schooner. The vessel is 102 feet (31 m) long. Its hull was originally wrought iron but was rebuilt in steel in the 1960s. It was used for transportation of various goods: sand, wood, stone, bricks and oyster shells. Now it is used for educational tours of New York Harbor. |  |

[43][44] |

| W. O. Decker | 1930 | Tugboat | The 52 foot (16 m) steam tug was built in Long Island City, Queens and first named Russell I. Subsequently, the engine was replaced by a 175 horsepower (130 kW) diesel engine. In 1986 the boat was transferred to the South Street Seaport museum. In 1996 it was entered in the National Register of Historic Places. | |

[45][46][47] |

| Wavertree | 1885 | Freighter | The ship was launched in Southampton. It is 325 feet (99 m) long including spars and 263 feet (80 m) on deck. The ship is the largest remaining wrought iron vessel. Initially it was used for transporting jute from east India to Scotland, and then was involved in the tramp trade. In 1947 it was converted into a sand barge, and in 1968 it was acquired by the South Street Seaport Museum. In 1978 the ship was entered in the National Register of Historic Places. | |

[48][49][50] |

Legend:

- – Designated National Historic Landmark and on the National Register of Historic Places

- – On the National Register of Historic Places

The Pioneer and W. O. Decker operate during favorable weather.

Transportation

South Street Seaport is currently served by the M15, M15 SBS New York City Bus route.[51]

New York Water Taxi directly serves South Street Seaport on Fridays, weekends, and holidays during the summer, while other New York Water Taxi, NYC Ferry, and SeaStreak ferries serve the nearby ferry slip at Pier 11/Wall Street daily.[52]

The Fulton Street/Fulton Center station complex (2 3 4 5 A C J Z N R W trains) is the closest New York City Subway station.[53] A new subway station, provisionally called Seaport, has been proposed as part of the unfunded Phase 4 of the Second Avenue Subway. Although this station will be located only 3 blocks from the Fulton Street station, there are no plans for a free transfer between them.[54]

In popular culture

Film:

- The seaport is a crucial location in the movie I Am Legend (2007), in which Will Smith's character broadcasts that he will be there each day at noon, to meet any fellow survivors of a virus outbreak.[55]

- The seaport was used in The Adjustment Bureau (2011) as well.

Games:

Music:

- The original Sub Pop version of Nirvana's "In Bloom" video was filmed here in 1990. The video features Kurt, Krist, and Chad clowning around inside the South Street Mall as well as on Wall Street.

- The venue is home to the Seaport Music Festival each summer.

Gallery

Aerial view

Aerial view Fulton Market

Fulton Market Pier 17

Pier 17- Corner of Front and Beekman Streets

- Peck Slip US Post Office, now reused as school[57]

See also

References

Notes

- 1 2 National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "South Street Seaport Historic District DesignationReport". nyc.gov. 1977. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995), The Encyclopedia of New York City, New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 0300055366, pp. 1214–1215

- ↑ Linda S. Cordell; et al. (2008). Archaeology in America: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 123. ISBN 0313021899.

- ↑ Sarah Harrison Smith (January 11, 2013). "Water and Land, Past and Present". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ Kroessler 2002, pp. 36–37

- ↑ Berube, Claude G.; Rodgaard, John A. (2005). A Call To The Sea. Potomac Books. p. 7. ISBN 1612342299.

- ↑ Jyh-Ming Yang (2008). Lost in Transliteration: The Tolerance of Unintelligibility in Chinese Bibliographic Records in Western Libraries. The University of Wisconsin -Madison. ProQuest. p. 61. ISBN 0549801332.

- ↑ Kroessler 2002, p. 52

- ↑ Patrick Bunyan (2010). All Around the Town: Amazing Manhattan Facts and Curiosities, Second Edition. Empire State Editions Series (2 ed.). Fordham Univ Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0823231747.

- ↑ Kroessler 2002, p. 70

- ↑ McKay 1969, p. 130

- ↑ Charles R. Geisst (2009). Encyclopedia of American Business History. Infobase Publishing. p. 389. ISBN 1438109873.

- ↑ Jessica Dailey (May 15, 2012). "Vintage Photos of the Fulton Fish Market in its Glory Days". Curbed NY. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ↑ Andrew Jacobs (November 11, 2005). "On Fish Market's Last Day, Tough Guys and Moist Eyes". The New York Times. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ↑ Kroessler 2002, p. 74

- ↑ Howard B. Rock (1989). The New York City Artisan: 1789 – 1825; a Documentary History. SUNY series in American labour history. SUNY Press. p. 113. ISBN 1438417594.

- ↑ Randall Gabrielan (2000). New York City's Financial District in Vintage Postcards. The postcard history series. Arcadia Publishing. p. 90. ISBN 0738500682.

- ↑ Ann L. Buttenwieser (1999). Manhattan Water-bound: Manhattan's Waterfront from the Seventeenth Century to the Present. Syracuse University Press. New York City History and Culture Series (2 ed.). p. 41. ISBN 0815628013.

- ↑ Kroessler 2002, p. 81

- ↑ Thomas Floyd-Jones (1914). Backward glances: reminiscences of an old New-Yorker. Unionist Gazette Association. pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Fordham. "Fordham College at Lincoln Center". Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ↑ Pogrebin, Robin (15 April 2015). "Susan Henshaw Jones to Leave Museum of the City of New York". New York Times. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ↑ "New York City News: Latest Headlines, Videos & Pictures". am New York. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ↑ "South Street Seaport Businesses Struggle to Recover from Sandy Flooding". DNAinfo New York. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ↑ Hazlett, Kurt (August 20, 2004). "General Growth Buys Rouse Co. in $12.6 Billion Deal". National Real Estate Investor.

- ↑ "General Growth Properties emerges from bankruptcy". November 9, 2010.

- ↑ America's National Maritime Museum Designation Act, TheOrator.net. Accessed September 18, 2007.

- ↑ Pier Staff. "Extraordinary places". Howard Hughes Corporation. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ↑ Lower Manhattan Staff. "Seaport District NYC". South Street Seaport. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ↑ Official Guide Staff. "pier 15, south street seaport". NYC Official Guide. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ↑ "Ambrose". South Street Seaport Museum. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ Bill Sanderson (April 25, 2011). "Abandoning ships: City's old vessels lost in fog of debt, neglect". New York Post. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ Stephen Nessen (March 5, 2012). "Ambrose Lightship Returns to South Street Seaport Museum". WNYC. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ MarlaDiamond (April 25, 2011). "South Street Seaport Museum Ships Falling Apart". CBS. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ "LIGHTSHIP NO. 87 "AMBROSE"". U.S. National ParkService. Retrieved April 15, 2014.

- ↑ Kevin J. Foster (1988). "Lightship No. 87 "Ambrose" National Historic Landmark Study". US National Park Service. Retrieved April 15, 2014.

- ↑ Arthur G. Adams (1996). The Hudson River Guidebook (2 ed.). Fordham University Press. p. 22. ISBN 0823216799.

- ↑ "Lettie G. Howard". South Street Seaport Museum. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ Barbara La Rocco (2004). Going Coastal New York City. Going Coastal, Inc. p. 192. ISBN 0-9729803-0-X.

- ↑ "LETTIE G. HOWARD (Schooner)". U.S. National ParkService. Retrieved April 15, 2014.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form" (PDF). US National Park Service.

- ↑ "Pioneer". South Street Seaport Museum.

- ↑ AdamSachs. "Pioneer Schooner – Sail Back In Time". New York Magazine. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ "W. O. Decker". South Street Seaport Museum. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ PaulFreireich (July 20, 2003). "Q & A – New York by Tugboat". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Tug W.O. Decker". The Travels of Tug 44. Retrieved April 15, 2014.

- ↑ "W. O. Decker". South Street Seaport Museum. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ Dan Michael Worrall (2009). The Anglo-German Concertina: A SocialHistory. p. 1. ISBN 0982599609.

- ↑ Braynard, Frank Osborn (1993). The Tall Ships of Today in Photographs. Dover Publications. pp. 45–46. ISBN 9780486271637.

- ↑ "Manhattan Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. May 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- ↑ "Ferry Information". NYCDOT. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ↑ "Subway Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. June 25, 2017. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ↑ "MTA Capital Construction – Second Avenue Subway: Project Description". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ Mondello, Bob. "I Am Legend a One-Man American Metaphor", NPR, December 14, 2017. "There's not a person in sight anywhere — except Robert Neville, who travels, when the sun is highest in the sky, to the South Street Seaport, to broadcast the same message he's been broadcasting for almost three years: 'If anyone is out there, I can provide food, shelter, security. If there's anybody out there ... you are not alone.'"

- ↑ "Pier 17 – Crysis 2 Map Focus". EA. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Officials Show Design of New Peck Slip School in Old Post Office Building". Retrieved March 14, 2016.

Sources

- Lindgren, James Michael (2014). Preserving South Street Seaport: the dream and reality of a New York urban renewal district. New York University Press: New York. ISBN 9781479822577.

- Norman J. Brouwer. South Street Seaport.

- Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995), The Encyclopedia of New York City, New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 0300055366

- Jeffrey A. Kroessler. New York Year by Year: A Chronology of the Great Metropolis. - NYU Press, 2002. ISBN 0814747515 .

- Richard Cornelius McKay. South Street: A Maritime History of New York. - 2. - Ardent Media, 1969.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to South Street Seaport. |

- Official website

- South Street Seaport Museum

- Interactive Map of the Seaport – Seaport Cultural Association

- City of Albany: North Waterfront Redevelopment Strategy

- A digital history of South Street Seaport by Fordham University students

- Video profile of the historic Fulton Ferry Hotel at South Street Seaport

- Image gallery

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. NY-156, "South Street Seaport, Piers 17 & 18, South Street into East River at Fulton Street, New York, New York County, NY", 11 photos, 9 data pages, 1 photo caption page

.jpg)