McAlester, Oklahoma

| McAlester, Oklahoma | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

Downtown McAlester | |

|

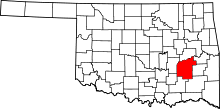

Location of McAlester, Oklahoma | |

McAlester, Oklahoma Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 34°55′59″N 95°45′59″W / 34.93306°N 95.76639°WCoordinates: 34°55′59″N 95°45′59″W / 34.93306°N 95.76639°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oklahoma |

| County | Pittsburg |

| Area | |

| • Total | 15.8 sq mi (41.0 km2) |

| • Land | 15.7 sq mi (40.6 km2) |

| • Water | 0.1 sq mi (0.4 km2) |

| Elevation | 735 ft (224 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 18,363 |

| • Density | 1,133.1/sq mi (437.5/km2) |

| Time zone | Central (CST) (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) |

| ZIP codes | 74501-74502 |

| Area code(s) | 539/918 |

| FIPS code | 40-44800[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1095202[2] |

| Website | McAlester, Oklahoma official website |

McAlester is a city in and county seat of Pittsburg County, Oklahoma, United States.[3] The population was 18,363 at the 2010 census, a 3.4 percent increase from 17,783 at the 2000 census,[4] making it the largest city in the former Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, followed by Durant. The town gets its name from J.J. McAlester, an early settler and businessman, who later became Lieutenant Governor of Oklahoma.[4]

McAlester is the home of the Oklahoma State Penitentiary, site of an "inside the walls" prison rodeo from which ESPN's SportsCenter once broadcast. Oklahomans sometimes refer to the state prison simply as "Big Mac" or "McAlester".[5]

McAlester is home to many of the employees of the McAlester Army Ammunition Plant. This facility makes essentially all of the bombs used by the United States military. In 1998 McAlester became the home of the Defense Ammunition Center (DAC) which moved from Savanna, Illinois, and relocated as a tenant on McAlester Army Ammunition Plant.

History

.jpg)

The crossing of the east-west California Road with the north-south Texas Road formed a natural point of settlement in Tobucksy County of the Choctaw Nation. Alyssia Young, who emigrated from Mississippi to the Indian Territory, first established a settlement at the intersection of the two roads in 1838. The town was named Perryville after James Perry, member of a Choctaw family, who established a trading post.[6] At one time Perryville was the capital of the Choctaw Nation and County Seat of Tobucksy County. During the American Civil War, the Choctaw allied with the Confederate States of America (CSA) as the war reached Indian Territory.[7]

A depot providing supplies to Confederate Forces in Indian Territory was set up at Perryville. On August 26, 1863 a force of 4,500 Union soldiers crossed the Canadian River and destroyed the Confederate munitions depot at Perryville. This became known as the Battle of Perryville, Indian Territory. Union Major General James G. Blunt, finding the Confederate supplies and realizing that Perryville was a major supply depot for Confederate forces ordered the town burned. The town was rebuilt, but never reached its prewar glory or population.

After the end of the Civil War in 1865, Captain James Jackson McAlester (usually known as J. J. McAlester), obtained a job with the trading company of Reynolds and Hannaford. McAlester convinced the firm to locate a general store at Tupelo in the Choctaw Nation. McAlester had learned of coal deposits in Indian Territory during the War Between the States while serving as a Captain with the 22nd Arkansas Volunteer Infantry (Confederate). At Fort Smith, Arkansas before going to work with Reynolds and Hannaford, McAlester had received maps of the coal deposits from engineer Oliver Weldon, who had served with McAlester during the war.[8]

Weldon had worked for the U.S. surveying Indian Territory before the war and knew of the rich coal deposits. Hearing of the railroad plans to extend through Indian Territory and knowing that rich deposits of coal were in an area north of the town of Perryville, McAlester convinced Reynolds and Hannaford that Bucklucksy would be a more suitable and profitable location for the trading post.[lower-alpha 1] McAlester constructed a trading post/general store at that location in late 1869 (Presley 1978, p. 72).The Bucklucksy general store was an immediate success, but McAlester recognized an even greater opportunity in the abundance of coal deposits in the area, so he began obtaining rights to the coal deposits from the Choctaws, anticipating the impending construction of a rail line through Indian Territory.[8]

As the first railroad to extend its line to the northern border of Indian Territory, the Union Pacific Railway Southern Branch earned right of way and a liberal bonus of land to extend the line to Texas. Several New York businessmen, including Levi P. Morton, Levi Parsons, August Belmont, J. Pierpont Morgan, George Denison and John D. Rockefeller were interested in extending rail line through Indian Territory, and the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad, familiarly called the Katy Railroad, began its corporate existence in 1865 toward that end. Morton and Parsons selected a site near the Kansas Indian Territory border where they incorporated a settlement named Parsons, Kansas in 1871.[8]

That same year, J.J. McAlester, after buying out Reynolds’ share of the trading post, journeyed with a sample of coal to the railroad town in hopes of persuading officials to locate the line near his store at Bucklucksy. The location of the trading post on the Texas Road weighed in its favor, given that the Katy Railroad line construction roughly followed the Shawnee Trail – Texas Road route southward to the Red River. The line reached Bucklucksy in 1872, and Katy Railroad officials named the railway stop McAlester (Nesbitt 1933, pp. 760–61).

With the coming of the railroad, businesses in nearby Perryville began relocating to be near the McAlester Rail Depot, marking the end of Perryville and the beginning of McAlester. On August 22, 1872, J.J. McAlester married Rebecca Burney (1841 – May 4, 1919). She was a member of the Chickasaw Nation, which made it possible for McAlester to gain citizenship and the right to own property (including mineral rights to the coal deposits in both the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations). McAlester, quickly obtained land near the intersection of the north-south and east-west rail lines, where he opened a second general store and continued doing business selling coal to the railroads.[4]

Fritz Sittle (Sittel), a Choctaw citizen by marriage and one of the first settlers in the area, urged visiting newspaperman Edwin D. Chadick in 1885 to pursue the possibility of establishing an east-west rail line to run through the coal mining district at Krebs that would connect with the north-south line at McAlester. Chadick eventually found financing and established the Choctaw Coal and Railway in 1888, but was unable to come to terms with J.J. McAlester over the issue of right of way.

In the 1870s, miners from Pennsylvania arrived in McAlester to work in the coal mines.[9] Miners of Italian origin arrived in McAlester in 1874.[9]

Chadick and his investors purchased land to the south of McAlester's General Store, and where the two rail lines crossed formed a natural trading crossroads, and quickly became a bustling community designated as South McAlester.[lower-alpha 2] South McAlester grew much more rapidly than North McAlester. The 1900 census showed a population of 3,470 for the former and 642 for the latter.[4]

The two towns operated as somewhat separate communities until 1907, when the United States Congress passed an act joining the two communities as a single municipality, the action being required since the towns were under federal jurisdiction in Indian Territory. The separate entities of McAlester and South McAlester were combined under the single name McAlester, with office-holders of South McAlester as officials of the single town. Designation as a single community by the United States Post Office came on July 1, 1907, nearly five months before Oklahoma Statehood, which caused a redrawing of county lines and designations, causing the majority of Tobucksy County to fall within the new lines of Pittsburg County. The city had 8,144 inhabitants upon statehood, more than a fourth of which were foreign-born.[9]

McAlester was the site of the 2004 trial of Terry Nichols on Oklahoma state charges related to the Oklahoma City bombing (1995). On December 25, 2000 an ice storm hit the area leaving residents without electrical service and water for more than two weeks; in January 2007 another devastating ice storm crippled the city, leaving residents without power and water for more than a week.[8]

Geography

McAlester is located at the intersection of U.S. Route 69 and U.S. Route 270, in Pittsburg County, Oklahoma.[10] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 41 square miles (110 km2), of which 40.6 square miles (105 km2) is land.

Neighboring communities

|

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1900 | 646 | — | |

| 1910 | 11,774 | 1,722.6% | |

| 1920 | 10,632 | −9.7% | |

| 1930 | 11,804 | 11.0% | |

| 1940 | 12,401 | 5.1% | |

| 1950 | 17,878 | 44.2% | |

| 1960 | 17,419 | −2.6% | |

| 1970 | 18,802 | 7.9% | |

| 1980 | 17,255 | −8.2% | |

| 1990 | 16,370 | −5.1% | |

| 2000 | 17,783 | 8.6% | |

| 2010 | 18,383 | 3.4% | |

| Est. 2015 | 18,310 | [11] | −0.4% |

| Sources:[1][12][13][14][15][16] | |||

As of the 2000 census,[1] there were 17,783 people, 6,584 households, and 4,187 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,133.1 people per square mile (437.6/km²). There were 7,374 housing units at an average density of 469.9 per square mile (181.5/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 74.72% White, 8.68% African American, 10.48% Native American, 0.39% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 1.29% from other races, and 4.38% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.04% of the population.

There were 6,584 households out of which 29.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.6% were married couples living together, 13.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.4% were non-families. 33.7% of all households were made up of individuals and 16.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.31 and the average family size was 2.93.

In the city, the population was spread out with 22.2% under the age of 18, 8.7% from 18 to 24, 30.4% from 25 to 44, 20.8% from 45 to 64, and 18.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females there were 107.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 108.2 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $28,631, and the median income for a family was $36,480. Males had a median income of $29,502 versus $19,455 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,694. About 16.1% of families and 19.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 26.8% of those under age 18 and 11.6% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Agriculture and coal mining supported the city's economy around the turn of the 20th Century, Cotton was the main cash crop, and McAlester had three cotton gins and one cotton compress. However, a boll weevil infestation destroyed the local cotton production,Meanwhile, railroads converted from coal to oil as their primary fuel, which marked the decline of the coal industry in this area.[17]

.

The Oklahoma State Penitentiary is a large source of employment and local revenue in McAlester.[17][18]

During World War II, the U.S. Government built the Naval Ammunition Plant a few miles south of McAlester. In 1947, the facility became the U.S. Army Ammunition Plant. It is still the main location for the production and storage of ammunition for the armed forces in the United States.[17]

Government and infrastructure

Two Oklahoma Department of Corrections facilities, the Oklahoma State Penitentiary and the Jackie Brannon Correctional Center, are in McAlester.[19][20]

Organizations

Pride in McAlester is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization established in April 2008. In addition to providing assistance and opportunity for recycling, the organization provides educational services and operates a Flea Market allowing community members to recycle and reuse most materials. The organization participates in scholarship opportunities, community functions, and operates citywide cleanup events.[21]

Education

McAlester Public Schools operates public schools. The McAlester Public Library is located in McAlester. The current library was built in 1970. As of 2010 the city has plans to build a new library.[22] The Friends of the McAlester Public Library is financing the new branch.[23]

McAlester includes Kiamichi Technology Center which has enrollment of over 300 students per school year. There is also an extension of Eastern Oklahoma State College which partners with Southeastern Oklahoma State University and East Central University.

Transportation

|

Points of interest

Notable people

- Carl Albert, Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives

- Melva Blancett, actress[25]

- John Berryman, poet

- Mary Blair, artist, Disney animator

- Ridge Bond, actor/dinger

- Riley Brett, race car driver

- Quentin Brooks, Olympian athlete[26]

- Edwin H. Burba, Jr., U.S. Army four-star general

- Lynn Cartwright, actress

- Wilburn Cartwright, U.S. Representative from Oklahoma

- W.H.H. Clayton, U.S. District Court Judge

- Bennie L. Davis, U.S. Air Force four-star general

- Bob Dickson, professional golfer

- Jerry Jewell, voice actor affiliated with Funimation

- Levi Parham, singer-songwriter

- Clonie Gowen, professional gambler

- Steve King, NFL football player

- Steven T. Kuykendall, U.S. Representative from California

- Pepper Martin, Major League Baseball player

- J. J. McAlester, pioneer, for whom McAlester was named

- Pake McEntire, singer

- Reba McEntire, singer/actress

- Susie McEntire-Eaton, singer

- Beverlee McKinsey, actress

- George Nigh (b. 1927), politician, Governor of Oklahoma (1979 - 1987), was born in McAlester

- Rev. W. Mark Sexson, founder of the International Order of the Rainbow for Girls[27]

- Gene Stipe, longest-serving member of the Oklahoma Senate, represented McAlester (1957–2003)

- Steven W. Taylor (b. 1949), attended high school in McAlester, mayor of McAlester (1982 - 1984), Oklahoma Supreme Court Justice (2004 - 2016), Oklahoma Supreme Court Chief Justice (2011 - 2013)

- Edward Lloyd Thomas, Confederate General

- Wade Watts, Baptist Minister; civil rights activist

- Walter L. Weaver, U.S. Representative from Ohio

- Michael Wilson, screenwriter

NRHP sites

The following sites in McAlester are listed on the National Register of Historic Places:

|

|

References

- ↑ Bucklucksy was an unincorporated community north of McAlester until part of it was submerged by the creation of Lake Eufaula.

- ↑ South McAlester was about Template:Convert 1.5 south of the original town, which became known familiarly as North McAlester or North Town, although early U.S. Census records simply identified it as McAlester.[4]

Further reading

- Nesbitt, Paul (1933), "J.J. McAlester", Chronicles of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Historical Society (published June 1933), 11 (2), pp. 758–64, ISSN 0009-6024, OCLC 1554537, retrieved 2007-08-16.

- Presley, Mrs. Leister E., ed. (1978), "Biography of J. T. Hannaford - Conway Co, AR", The Goodspeed biographical and historical memoirs of western Arkansas ; Yell, Pope, Johnson, Logan, Scott, Polk, Montgomery, and Conway counties, Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press (published June 1978), p. 72, ISBN 978-0-89308-084-6, OCLC 5729534, LCC: F411 .B67 1978 Reprint of the 1891 ed. of Biographical and historical memoirs of western Arkansas, published by the Southern Pub. Co., Chicago, and the 1890 ed. of Historical reminiscences and biographical memoirs of Conway County, Arkansas, published by Arkansas Historical Pub. Co., Little Rock. Includes new indexes.

- McAlester Chamber of Commerce (2007-09-01), Living In McAlester: Location/ Transportation, retrieved 2007-09-01

- Dunbar, Trevor (January 14, 2007). "Ice storm". McAlester News-Capital. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to McAlester, Oklahoma. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article McAlester. |

- McAlester Chamber of Commerce

- Community Profile

- McAlester Photos

- City of McAlester

- Map from Center for Spatial Analysis

- 1 2 3 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board of Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Shuller, Thurman.Shuller, Thurman. "McAlester" profile, Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture; accessed February 12, 2017.

- ↑ Brooks, Les. "McAlester Prison Riot", Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, Oklahoma Historical Society; accessed September 2, 2015.

- ↑ Oklahoma: A Guide to the Sooner State. Federal Writers Project, pg. 340 (1941); retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ↑ http://www.wbtsinindianterritory.com.istemp.com

- 1 2 3 4 "History of McAlester." City of McAlester. Accessed February 13, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Stanley Clark, "Immigrants in the Choctaw Coal Industry", The Chronicles of Oklahoma 33 (Winter 1955-56).

- ↑ Oklahoma Municipal Government, Oklahoma Almanac, 2005, p. 535. (accessed October 1, 2013)

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Population-Oklahoma" (PDF). U.S. Census 1910. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ "Population-Oklahoma" (PDF). 15th Census of the United States. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ↑ "Number of Inhabitants: Oklahoma" (PDF). 18th Census of the United States. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ "Oklahoma: Population and Housing Unit Counts" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ "Incorporated Places and Minor Civil Divisions Datasets: Subcounty Population Estimates: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 LeFlore, Jeanne. "McAlester History." McAlester News. July 23, 2013. Accessed February 14, 2017.

- ↑ Shapiro, Dean M. "Kirksey." Crime Library. Retrieved on July 24, 2010.

- ↑ "Oklahoma State Penitentiary", Oklahoma Department of Corrections; retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ↑ ""Jackie Brannon Correctional Center", Oklahoma Department of Corrections; retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ↑ Pride in McAlester, prideinmcalester.com; accessed February 14, 2017.

- ↑ "Friends of the Library." McAlester Public Library. Retrieved on November 22, 2010.

- ↑ "fol_brochure_thumb.jpg." McAlester Public Library. Retrieved on November 22, 2010.

- ↑ (McAlester Chamber of Commerce 2007)

- ↑ "Melva Blancett obituary". McAlester News-Capital. 2010-03-11. Retrieved 2010-03-30.

- ↑ "Quentin Brooks profile". Sports Reference. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ↑ "Biography of William Mark Sexson". Winston-Salem, North Carolina: Grand Assembly of North Carolina. Archived from the original on 2007-12-25. Retrieved 2008-11-17.