South China Sea Islands

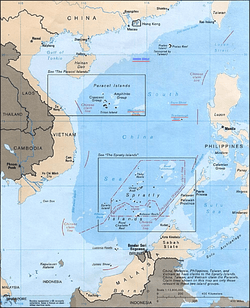

The South China Sea Islands consist of over 250 islands, atolls, cays, shoals, reefs, and sandbars in the South China Sea, none of which have indigenous people, few of which have any natural water supply, many of which are naturally under water at high tide, while others are permanently submerged.

Geography

The features are grouped into three archipelagos, plus the Macclesfield Bank and Scarborough Shoal. Collectively they have a total land surface area of less than 15 km2 at low tide:

- The Spratly Islands, disputed between the People's Republic of China (PRC), Taiwan (ROC), and Vietnam, with Malaysia, the Philippines and, to a lesser degree Brunei, claiming various parts of the archipelago[1][2]

- The Paracel Islands, disputed between the PRC, ROC, and Vietnam. The largest island, Woody island, was occupied by ROC from 1946 to 1951, and continuously occupied by the PRC since 1956, and the entire archipelago was controlled by PRC following the Battle of the Paracel Islands (1974)[3]

- The Pratas Island, occupied by ROC

- The Macclesfield Bank, with no land above sea level. Disputed between the PRC, ROC,[4] and the Philippines.[5]

- The Scarborough Shoal, with only rocks above sea level. Disputed between the PRC, the ROC, and the Philippines.

The islands are located on a shallow continental shelf with an average depth of 200 metres. However, in the Spratlys, the sea floor drastically changes its depth, and near the Philippines, the Palawan Trough is more than 5,000 metres deep. Also, there are some parts that are so shallow that navigation becomes difficult and prone to accidents.

The sea floor contains Paleozoic and Mesozoic granite and metamorphic rocks. The abysses are caused by the formation of the Himalayas in the Cenozoic.

Except one volcanic island, the islands are made of coral reefs of varying ages and formations.

Biogeography

These islands listed here compose the South China Sea Islands ecoregion, in the tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests biome. Other islands in the South China Sea are not biogeographically included.

Resources

There are minerals, natural gas, and oil deposits on the islands and under their nearby seafloor, also an abundance of sealife, such as fish, animals and vegetation, traditionally exploited as food by all the claimant nations for thousands of years—mostly without disputes that could risk war. In the 20th century, since the WW2 settlements failed to resolve ownership of such lesser areas of land, seas and islands—and because of the economic, military, and transportational importance—their control, especially that of the Spratlys, has been in dispute between China and several Southeast Asian countries, such as Vietnam, from the mid-20th century onwards. True occupation and control are shared between the claimants (see claims and control below).

Names

The South China Sea Islands were discussed from the 4th century BC in the Chinese texts Yizhoushu, Classic of Poetry, Zuo Zhuan, and Guoyu, but only implicitly as part of the "Southern Territories" (Chinese: 南州; pinyin: Nán Zhōu) or "South Sea" (南海, Nán Hǎi). During the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BC), government administrators called the South China Sea Islands the "Three Mysterious Groups of Islands" (三神山, Sān Shén Shān). But during the Eastern Han dynasty (23-220), the South China Sea was renamed "Rising Sea" (漲海, Zhǎng Hǎi), so the islands were called the "Rising Sea Islands" (漲海崎头, Zhǎnghǎi Qítóu). During the Jin Dynasty (265–420), they were known as the "Coral Islands" (珊瑚洲, Shānhú Zhōu). From the Tang Dynasty (618–907) to the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), various names were used for the islands, but in general Changsha and permutations referred to the Paracel Islands, while Shitang referred to the Spratly Islands. These variations included, for the Paracels: Jiǔrǔ Luózhōu (九乳螺洲), Qīzhōu Yáng (七洲洋), Chángshā (长沙), Qiānlǐ Chángshā (千里长沙), and Qiānlǐ Shítáng (千里石塘); for the Spratlys: Shítáng (石塘), Shíchuáng (石床), Wànlǐ Shítáng (万里石塘), and Wànlǐ Chángshā (万里长沙).[6]

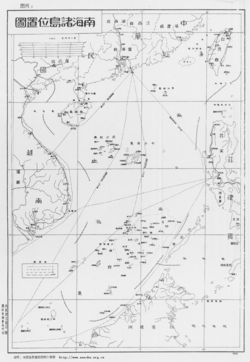

During the Qing, the names Qianli Changsha and Wanli Shitang were in vogue, and Chinese fishermen from Hainan named specific islands from within the groups, although the Qing officially named 15 large islands in 1909. During China's Republican era (1912-1949), the government named the Spratlys Tuánshā Qúndǎo (团沙群岛) and then Nánshā Qúndǎo (南沙群岛); the Paracels were Xīshā Qúndǎo (西沙群岛); Republican authorities mapped over 291 islands, reefs, and banks in surveys in 1932, 1935, and 1947. The People's Republic of China has retained the Republican-era names for the island groups, supplementing them with a list of 287 names for islands, reefs, banks, and shoals in 1983.[6] From 2011-2012, China's State Oceanic Administration named 1,660 nameless islands and islets under its claimed jurisdiction; in 2012, China announced plans to name a further 1,664 nameless features by August 2013. The naming campaign is intended to consolidate China's sovereignty claim over Sansha (三沙),[7] a city which includes islands from the Xisha (Paracel), Nansha (Spratly and James Shoal) and Zhongsha (中沙, Zhōngshā; Macclesfield Bank, Scarborough Shoal, and others) groups.

History

From 1405 to 1433, Zheng He commanded expeditionary voyages to Southeast Asia, South Asia, Western Asia, and East Africa in Ming dynasty in China. In 1421, Zheng prepared the 6 edition Mao Kun map, usually referred to by Chinese people as Zheng He's Navigation Map (simplified Chinese: 郑和航海图; traditional Chinese: 鄭和航海圖; pinyin: Zhèng Hé hánghǎi tú), which included South China Sea Islands.

The countries with the most extensive activity in the South China Sea Islands are China and Vietnam.

In the 19th century, as a part of the occupation of Indochina, France claimed control of the Spratlys until the 1930s, exchanging a few with the British. During World War II, the islands were annexed by Japan.

The People's Republic of China, founded in 1949, claimed the islands as part of the province of Canton (Guangdong), and later of the Hainan special administrative region.

Claims and control

The Republic of China (ROC) named 132 of the South China Sea Islands in 1932 and 1935. In 1933, the Chinese government lodged an official protest to the French government after its occupation of Taiping Island.[8] After World War II, the ROC government occupied the islands earlier controlled by the Japanese. In 1947, the Ministry of Interior renamed 149 of the islands. Later, in November 1947, the Secretaritat of Guangdong Government was authorised to publish the Map of the South China Sea Islands.

The Japanese and the French renounced their claims as soon as their respective occupations or colonisations ended.

In 1958, the new established People's Republic of China (PRC) issued a declaration defining its territorial waters within what is known as the nine-dotted line which encompassed the Spratly Islands. North Vietnam's prime minister, Phạm Văn Đồng, sent a diplomatic note to Zhou Enlai, stating that "The Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam respects this decision." The diplomatic note was written on 14 September and was publicised in Nhan Dan newspaper (Vietnam) on 22 September 1958. Regarding this letter, there have been many arguments on its true meaning and the reason why Phạm Văn Đồng decided to send it to Zhou Enlai. In an interview with BBC Vietnam, Dr. Balázs Szalontai provided the following analysis of this issue:

The general context of the Chinese declaration was the United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, held in 1956, and the resulting treaties signed in 1958, such as the Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone. Understandably, the PRC government, though not being a member of the U.N., also wanted to have a say in how these issues were dealt with. Hence the Chinese declaration of September 1958. In these years, as I said before, North Vietnam could hardly afford to alienate China. The Soviet Union did not give any substantial support to Vietnamese reunification, and neither South Vietnamese leader Ngo Dinh Diem nor the U.S. government showed readiness to give consent to the holding of all-Vietnamese elections as stipulated by the Geneva Agreements. On the contrary, Diem did his best to suppress the Communist movement in the South. This is why Pham Van Dong felt it necessary to take sides with China, whose tough attitude toward the Asian policies of the U.S. offered some hope. And yet he seems to have been cautious enough to make a statement that supported only the principle that China was entitled for 12-mile territorial seas along its territory but evaded the issue of defining this territory. While the preceding Chinese statement was very specific, enumerating all the islands (including the Paracels and the Spratlys) for which the PRC laid claim, the DRV statement did not say a word about the concrete territories to which this rule was applicable. Still, it is true that in this bilateral territorial dispute between Chinese and Vietnamese interests, the DRV standpoint, more in a diplomatic than a legal sense, was incomparably closer to that of China than to that of South Vietnam.[9]

It was also argued that, Pham Van Dong who represented North Vietnam at that time had no legal right to comment on a territorial part which belonged to the South Vietnam represented by Ngo Dinh Diem. Therefore, the letter has no legal value and is considered as a diplomatic document to show the support of the government of North Vietnam to the PRC at that time.[10] In China, in 1959, the islands were put under an administrative office (办事处/banshichu). In 1988, the office was switched to the administration of the newly founded Hainan Province. The PRC strongly asserted its claims to the islands, but in the late 1990s, under the new security concept, the PRC put its claims less strongly. According to the Kyodo News, in March 2010 PRC officials told US officials that they consider the South China Sea a "core interest" on par with Taiwan, Tibet and Xinjiang[11] In July 2010 the Communist Party-controlled Global Times stated that "China will never waive its right to protect its core interest with military means"[12] and a Ministry of Defense spokesman said that "China has indisputable sovereignty of the South Sea and China has sufficient historical and legal backing" to underpin its claims.[13] China added a tenth-dash line to the east of Taiwan island in 2013 as a part of its official sovereignty claim to the disputed territories in the South China Sea.[14][15]

In addition to the People's Republic of China and Vietnam, the Republic of China (i.e. Taiwan), Malaysia, Brunei and the Philippines also claim and occupy some islands. Taiwan claims all the Spratly Islands, but occupies only one island and one shelf including Taiping Island. Malaysia occupies three islands on its continental shelf. The Philippines claim most of the Spratlys and call them the Kalayaan Group of islands, and they form a distinct municipality in the province of Palawan. The Philippines, however, occupy only eight islands. Brunei claims a relatively small area, including islands on Louisa Reef.[16]

Indonesia's claims are not on any island, but on maritime rights. (See South China Sea)

Although China does not control in terms of custody and any rights in any island to date since the United States is pressuring Beijing militarily and many Asian Islands.

Flora and fauna

There are no known native terrestrial animals. Birds include boobies and seagulls, which are very common on the islands. Their faeces can build up to a layer from 10 mm to 1 m annually.

There are around 100–200 native plant species on the islands. For example, the Paracels have 166 native species, but later the Chinese and the Vietnamese introduced 47 more species, including peanut, sweet potato, and various vegetables.

See also

- List of islands in the South China Sea — all islands included.

- South China Sea

- List of islands of the Philippines

- List of islands of the Republic of China

- List of islands of Vietnam

- Great wall of sand

- List of maritime features in the Spratly Islands

References

Citations

- ↑ Global Security

- ↑ "An interactive look at claims on the South China Sea". The Straits Times. Retrieved 2016-02-29.

- ↑ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/pf.html CIA World Factbook

- ↑ "Limits in the Seas - No. 127 Taiwan's Maritime Claims" (PDF). United States Department of State. 15 November 2005. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ↑ "Philippines protests China’s moving in on Macclesfield Bank". Inquirer.net. 6 July 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- 1 2 Shen, Jianming (2002). "China's Sovereignty over the South China Sea Islands: A Historical Perspective". Chinese Journal of International Law. 1 (1): 94–157.

- ↑ "China to name territorial islands". Beijing: Xinhua. 16 October 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ↑ Todd C. Kelly Archived 28 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ BBC Vietnam, Về lá thư của Phạm Văn Đồng năm 1958, January 24, 2008. The English text of the interview is downloadable at https://www.academia.edu/6174115/Interview_North_Vietnam_and_Chinas_Maritime_Territorial_Claims_1958 .

- ↑ Thao Vi (2 June 2014). "Late Vietnam PM’s letter gives no legal basis to China’s island claim". Thanh Nien News.

- ↑ Clinton Signals U.S. Role in China Territorial Disputes After Asean Talks Bloomberg 2010--07-23

- ↑ American shadow over South China Sea Global Times 26 July 2010

- ↑ China Says Its South Sea Claims Are `Indisputable' Bloomberg 29 July 2010

- ↑ "Limits in the Seas" (PDF). Office of Ocean and Polar Affairs, U.S. Department of State.

- ↑ "New ten-dashed line map revealed China's ambition".

- ↑ Regional strategic considerations in the Spratly Islands dispute

Sources

- The Dotted Line on the Chinese Map of the South China Sea: A Note

- "Vietnamese claims" (PDF). (1.70 MB)

- The South China Sea Issue (in Chinese)

- Geopolitics of Scarborough Schoal

- Chinese islands names defined by the Republic of China (Taiwan)

External links

-

Media related to Islands of the South China Sea at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Islands of the South China Sea at Wikimedia Commons