Asian Americans

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

17,273,777[1][2] 5.4% of the total U.S. population (2015) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Throughout the United States, especially the New York City metropolitan area,[3] Greater Los Angeles area, San Francisco Bay Area, and major urban areas elsewhere | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

|

Christian (42%) Unaffiliated (26%) Buddhist (14%) Hindu (10%) Muslim (4%) Sikh (1%) Other (2%) including Jain, Zoroastrian, Shinto, and Chinese folk religion (Taoist and Confucian)[4] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Asian Americans of Hispanic and Latino ethnicity |

Asian Americans are Americans of Asian descent. The term refers to a panethnic group that includes diverse populations who have ancestral origins in East Asia, Southeast Asia, or South Asia, as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau.[5] This includes people who indicate their race(s) on the census as "Asian" or reported entries such as "Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, and Other Asian."[6] Asian Americans with no other ancestry comprise 4.8% of the U.S. population, while people who are Asian alone or combined with at least one other race make up 5.6%.[5]

Although migrants from Asia have been in parts of the contemporary United States since the 17th century, large-scale immigration did not begin until the mid-18th century. Nativist immigration laws during the 1880s-1920s excluded various Asian groups, eventually prohibiting almost all Asian immigration to the continental United States. After immigration laws were reformed during the 1940s-60s, abolishing national origins quotas, Asian immigration increased rapidly. Analyses of the 2010 census have shown that Asian Americans are the fastest growing racial or ethnic minority in the United States.[7]

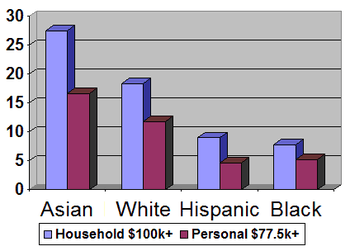

Starting in the first few years of the 2000 decade, Asian American earnings began exceeding all other racial groups for both men and women.[8] For example, in 2008 Asian Americans had the highest median household income overall of any racial demographic.[9][10] In 2012, Asian Americans had the highest educational attainment level and median household income of any racial demographic in the country.[11][12] In 2015, Asian American men were the highest earning racial group as they earned 117% as much as white American men and Asian-American women earned 106% as much as white American women.[8]

Despite this, a 2014 report from the Census Bureau reported that 12% of Asian Americans were living below the poverty line, while only 10.1% of non-Hispanic white Americans live below the poverty line.[13] Once country of birth and other demographic factors are taken into account, Asian Americans are no more likely than non-Hispanic whites to live in poverty.[14]

Terminology

As with other racial and ethnicity based terms, formal and common usage have changed markedly through the short history of this term. Prior to the late 1960s, people of Asian ancestry were usually referred to as Oriental, Asiatic, and Mongoloid.[15][16] Additionally, the American definition of 'Asian' originally included West Asian ethnic groups, particularly Afghan Americans, Jewish Americans, Armenian Americans, Assyrian Americans, and Arab Americans, although these groups are now considered Middle Eastern American.[17][18] The term Asian American was coined by historian Yuji Ichioka, who is credited with popularizing the term, to frame a new "inter-ethnic-pan-Asian American self-defining political group" in the late 1960s.[15] Changing patterns of immigration and an extensive period of exclusion of Asian immigrants have resulted in demographic changes that have in turn affected the formal and common understandings of what defines Asian American. For example, since the removal of restrictive "national origins" quotas in 1965, the Asian-American population has diversified greatly to include more of the peoples with ancestry from various parts of Asia.[19]

Today, Asian American is the accepted term for most formal purposes, such as government and academic research, although it is often shortened to Asian in common usage. The most commonly used definition of Asian American is the US Census Bureau definition, which includes all people with origins in the Far East, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent.[6] This is chiefly because the census definitions determine many government classifications, notably for equal opportunity programs and measurements.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "Asian person" in the United States is sometimes thought of as a person of East Asian descent.[20][21] In vernacular usage, "Asian" is often used to refer to those of East Asian descent or anyone else of Asian descent with epicanthic eyefolds.[22][23] This differs from the U.S. Census definition[6][24] and the Asian American Studies departments in many universities consider all those of East, South or Southeast Asian descent to be "Asian".[25]

Census definition

In the US Census, people with origins or ancestry in the Far East, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent are classified as part of the Asian race;[26] while those with origins or ancestry in North Asia (Russians, Siberians), Central Asia (Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Turkmens, etc.), Western Asia (diaspora Jews, Turks, Persians, West Asian Arabs, etc.), and the Caucasus (Georgians, Armenians, Azeris) are classified as "white" or "Middle Eastern".[27][28][29][30] As such, "Asian" and "African" ancestry are seen as racial categories for the purposes of the Census, since they refer to ancestry only from those parts of the Asian and African continents that are outside the Middle East and North Africa.

Before 1980, Census forms listed particular Asian ancestries as separate groups, along with white and black or negro.[31] Asian Americans had also been classified as "other".[32] In 1977, the federal Office of Management and Budget issued a directive requiring government agencies to maintain statistics on racial groups, including on "Asian or Pacific Islander".[33] The 1980 census marked the first classification of Asians as a large group, combining several individual ancestry groups into "Asian or Pacific Islander." By the 1990 census, "Asian or Pacific Islander (API)" was included as an explicit category, although respondents had to select one particular ancestry as a subcategory.[34][35] The 2000 census onwards separated the category into two separate ones, "Asian American" and "Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander."[36]

Debates

The definition of Asian American has variations that derive from the use of the word American in different contexts. Immigration status, citizenship (by birthright and by naturalization), acculturation, and language ability are some variables that are used to define American for various purposes and may vary in formal and everyday usage.[37] For example, restricting American to include only U.S. citizens conflicts with discussions of Asian American businesses, which generally refer both to citizen and non-citizen owners.[38]

In a PBS interview from 2004, a panel of Asian American writers discussed how some groups include people of Middle Eastern descent in the Asian American category.[39] Asian American author Stewart Ikeda has noted, "The definition of 'Asian American' also frequently depends on who's asking, who's defining, in what context, and why... the possible definitions of 'Asian-Pacific American' are many, complex, and shifting... some scholars in Asian American Studies conferences suggest that Russians, Iranians, and Israelis all might fit the field's subject of study."[40] Jeff Yang, of the Wall Street Journal, writes that the pan-ethnic definition of Asian American is a unique American construct, and as an identity is "in beta".[41]

Scholars have grappled with the accuracy, correctness, and usefulness of the term Asian American. The term "Asian" in Asian American most often comes under fire for encompassing a huge number of people with ancestry from (or who have immigrated from) a wide range of culturally diverse countries and traditions. In contrast, leading social sciences and humanities scholars of race and Asian American identity point out that because of the racial constructions in the United States, including the social attitudes toward race and those of Asian ancestry, Asian Americans have a "shared racial experience."[42] Because of this shared experience, the term Asian American is still a useful panethnic category because of the similarity of some experiences among Asian Americans, including stereotypes specific to people in this category.[42][43][44]

Demographics

The demographics of Asian Americans describe a heterogeneous group of people in the United States who can trace their ancestry to one or more countries in Asia.[45][46] Because Asian Americans compose 5% of the entire U.S. population, the diversity of the group is often disregarded in media and news discussions of "Asians" or of "Asian Americans."[47] While there are some commonalities across ethnic sub-groups, there are significant differences among different Asian ethnicities that are related to each group's history.[48][49] As of July 2015, California had the largest population of Asian Americans of any state, and Hawaii was the only state where Asian Americans were the majority of the population.[50]

The demographics of Asian Americans can further be subdivided into, as listed in alphabetical order:

- East Asian Americans, including Chinese Americans, Japanese Americans, Korean Americans, Mongolian Americans, and Taiwanese Americans.

- South Asian Americans, including Bangladeshi Americans, Bhutanese Americans, Indian Americans, Nepalese Americans, Pakistani Americans and Sri Lankan Americans

- Southeast Asian Americans, including Burmese Americans, Cambodian Americans, Filipino Americans, Hmong Americans, Indonesian Americans, Laotian Americans, Malaysian Americans, Mien Americans, Singaporean Americans, Thai Americans, and Vietnamese Americans.

Asian Americans include multiracial or mixed race persons with origins or ancestry in both the above groups and another race, or multiple of the above groups.

Language

In 2010, there were 2.8 million people (5 and older) who spoke a Chinese language at home;[51] after the Spanish language, it is the third most common language in the United States.[51] Other sizeable Asian languages are Tagalog, Vietnamese, and Korean, with all three having more than 1 million speakers in the United States.[51] In 2012, Alaska, California, Hawaii, Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Texas and Washington were publishing election material in Asian languages in accordance with the Voting Rights Act;[52] these languages include Tagalog, Mandarin Chinese, Vietnamese, Hindi and Bengali.[52] Election materials were also available in Gujarati, Japanese, Khmer, Korean, and Thai.[53] According to a poll conducted by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund in 2013, it found that 48 percent of Asian Americans considered media in their native language as their primary news source.[54]

According to the 2000 Census, the more prominent languages of the Asian American community include the Chinese languages (Cantonese, Taishanese, and Hokkien), Tagalog, Vietnamese, Korean, Japanese, Hindi, Urdu, and Gujarati.[55] In 2008, the Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Tagalog, and Vietnamese languages are all used in elections in Alaska, California, Hawaii, Illinois, New York, Texas, and Washington state.[56]

Religion

A 2012 Pew Research Center study found the following breakdown of religious identity among Asian Americans:[57]

- 42% Christian

- 26% unaffiliated with any religion

- 14% Buddhist

- 10% Hindu

- 4% Muslim

- 2% other religion

- 1% Sikh

The percentage of Christians among Asian Americans has declined sharply since the 1990s, chiefly due to largescale immigration from countries in which Christianity is a minority religion (China and India in particular). In 1990, 63% of the Asian Americans identified as Christians, while in 2001 only 43% did.[58] This development has been accompanied by a rise in traditional Asian religions, with the people identifying with them doubling during the same decade.[59]

History

Early immigration

As Asian Americans originate from many different countries, each population has its own unique immigration history.[11]

Filipinos have been in the territories that would become the United States since the 16th century.[60] The earliest known arrival is that of "Luzonians" in Morro Bay, California on board the Manila-built galleon ship Nuestra Senora de Esperanza in 1587, when both the Philippines and California were colonies of the Spanish Empire.[61][62] Romani people began emigrating to North America in colonial times, with small groups recorded in Virginia and French Louisiana. Larger-scale Roma emigration to the United States would follow subsequently. In 1635, an "East Indian" is listed in Jamestown, Virginia;[63] preceding wider settlement of Indian immigrants on the East Coast in the 1790s and the West Coast in the 1800s.[64] In 1763, Filipinos established the small settlement of Saint Malo, Louisiana, after fleeing mistreatment aboard Spanish ships.[65] Since there were no Filipino women with them, these Manilamen, as they were known, married Cajun and Native American women.[66] The first Japanese person to come to the United States, and stay any significant period of time was Nakahama Manjirō who reached the East Coast in 1841, and Joseph Heco became the first Japanese American naturalized US citizen in 1858.[67][68]

Chinese sailors first came to Hawaii in 1789,[69][70] a few years after Captain James Cook came upon the island. Many settled and married Hawaiian women. Most Chinese, Korean and Japanese immigrants in Hawaii arrived in the 19th century as laborers to work on sugar plantations.[71] There were thousands of Asians in Hawaii when it was annexed to the United States in 1898.[72] Later, Filipinos also came to work as laborers, attracted by the job opportunities, although they were limited.[73][74]

Large-scale migration from Asia to the United States began when Chinese immigrants arrived on the West Coast in the mid-19th century.[75] Forming part of the California gold rush, these early Chinese immigrants participated intensively in the mining business and later in the construction of the transcontinental railroad.[76] By 1852, the number of Chinese immigrants in San Francisco had jumped to more than 20,000. A wave of Japanese immigration to the United States began after the Meiji Restoration in 1868.[77] In 1898, all Filipinos in the Philippine Islands became American nationals when the United States took over colonial rule of the islands from Spain following the latter's defeat in the Spanish–American War.[78]

Exclusion era

Under United States law during this period, particularly the Naturalization Act of 1790, only "free white persons" were eligible to naturalize as American citizens. Ineligibility for citizenship prevented Asian immigrants from accessing a variety of rights such as voting.[79] In a pair of cases, Ozawa v. United States (1922) and United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923), the Supreme Court upheld the racial qualification for citizenship and ruled that Asians were not "white persons." Second-generation Asian Americans, however, could become U.S. citizens due to the birthright citizenship clause of the Fourteenth Amendment; this guarantee was confirmed as applying regardless of race or ancestry by the Supreme Court in United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898).[80][81]

From the 1880s to the 1920s, the United States passed laws inaugurating an era of exclusion of Asian immigrants. Although the absolute numbers of Asian immigrants were small compared to that of immigrants from other regions, much of it was concentrated in the West, and the increase caused some nativist sentiment known as the "yellow peril". Congress passed restrictive legislation prohibiting nearly all Chinese immigration in the 1880s.[82] Japanese immigration was sharply curtailed by a diplomatic agreement in 1907. The Asiatic Barred Zone Act in 1917 further barred immigration from South Asia (then-British India), Southeast Asia, and the Middle East.[83] The Immigration Act of 1924 provided that no "alien ineligible for citizenship" could be admitted as an immigrant to the United States, consolidating the prohibition of Asian immigration.[84][85]

Postwar immigration

World War II-era legislation and judicial rulings gradually increased the ability of Asian Americans to immigrate and become naturalized citizens. Immigration rapidly increased following the enactment of the Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments of 1965 as well as the influx of refugees from conflicts occurring in Southeast Asia such as the Vietnam War. Asian American immigrants have a significant percentage of individuals who have already achieved professional status, a first among immigration groups.[86]

The Migration Policy Institute reports that the number of Asian immigrants to the United States "grew from 491,000 in 1960 to about 12.8 million in 2014, representing a 2,597 percent increase."[87] From 2000 to 2010, the Asian American population was the fastest growing group according to the 2010 U.S. Census.[11][88][89] By 2012, the growth of Asian American population overtook the growth of Latino American population according to the Pew Research Center; it also found that illegal immigration from Asia was significantly less than from Latin America.[90] In 2015, Pew Research Center found that from 2010 to 2015 more immigrants came from Asia than from Latin America, and that since 1965 Asians have made up a quarter of all immigrants.[91]

Asians have made up an increasing proportion of the foreign-born Americans: "In 1960, Asians represented 5 percent of the U.S. foreign-born population; by 2014, their share grew to 30 percent of the nation's 42.4 million immigrants."[87] As of 2016, "Asia is the second-largest region of birth (after Latin America) of U.S. immigrants."[87] In 2013, China surpassed Mexico as the top single country of origin for immigrants to the U.S.[92] Asian immigrants "are more likely than the overall foreign-born population to be naturalized citizens"; in 2014, 59% of Asian immigrants had U.S. citizenship, compared to 47% of all immigrants.[87] Postwar Asian immigration to the U.S. has been diverse: in 2014, 31% of Asian immigrants to the U.S. were from East Asian (predominately China and Korea); 27.7% were from South Central Asia (predominately India); 32.6% were from Southeastern Asia (predominately the Philippines and Vietnam) and 8.3% were from Western Asia.[87]

Asian American movement

The Asian American movement refers to a pan-Asian movement in the United States in which Americans of Asian descent came together to fight against their shared oppression and to organize for recognition and advancement of their shared cause during the 1960s to the early 1980s. According to William Wei, the movement was "rooted in a past history of oppression and a present struggle for liberation."[93] This occurred around the same time as the Chicano movement, Civil Rights Movement, American Indian Movement and the gay liberation movement.

Notable people

Arts and entertainment

Asian Americans have been involved in the entertainment industry since the first half of the 19th century, when Chang and Eng Bunker (the original "Siamese Twins") became naturalized citizens.[94] Acting roles in television, film, and theater were relatively few, and many available roles were for narrow, stereotypical characters. More recently, young Asian American comedians and film-makers have found an outlet on YouTube allowing them to gain a strong and loyal fanbase among their fellow Asian Americans.[95] There have been several Asian American-centric television shows in American media, beginning with Mr. T and Tina in 1976, and as recent as Fresh Off the Boat in 2015.[96] Throughout the 1990s there was a growing amount of Asian American queer writings[97] and today the list of contributing writers is long. To name a few: Merle Woo (1941), Willyce Kim (1946), Russel Leong (1950), Kitty Tsui (1952), Dwight Okita (1958), Norman Wong (1963), Tim Liu (1965), Chay Yew (1965) and Justin Chin (1969).

Business

When Asian Americans were largely excluded from labor markets in the 19th century, they started their own businesses. They have started convenience and grocery stores, professional offices such as medical and law practices, laundries, restaurants, beauty-related ventures, hi-tech companies, and many other kinds of enterprises, becoming very successful and influential in American society. They have dramatically expanded their involvement across the American economy. Asian Americans have been disproportionately successful in the hi-tech sectors of California's Silicon Valley, as evidenced by the Goldsea 100 Compilation of America's Most Successful Asian Entrepreneurs.[98]

Compared to their population base, Asian Americans today are well represented in the professional sector and tend to earn higher wages.[99] The Goldsea compilation of Notable Asian American Professionals show that many have come to occupy high positions at leading U.S. corporations, including a surprising number as Chief Marketing Officers.[100]

Asian Americans have made major contributions to the American economy. In 2012, Asian Americans own 1.5 million businesses, employ around 3 million people who earn an annual total payroll of around $80 billion.[88] Fashion designer and mogul Vera Wang, who is famous for designing dresses for high-profile celebrities, started a clothing company, named after herself, which now offers a broad range of luxury fashion products. An Wang founded Wang Laboratories in June 1951. Amar Bose founded the Bose Corporation in 1964. Charles Wang founded Computer Associates, later became its CEO and chairman. David Khym founded hip-hop fashion giant Southpole (clothing) in 1991. Jen-Hsun Huang co-founded the NVIDIA corporation in 1993. Jerry Yang co-founded Yahoo! Inc. in 1994 and became its CEO later. Andrea Jung serves as Chairman and CEO of Avon Products. Vinod Khosla was a founding CEO of Sun Microsystems and is a general partner of the prominent venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers. Steve Chen and Jawed Karim were co-creators of YouTube, and were beneficiaries of Google's $1.65 billion acquisition of that company in 2006. In addition to contributing greatly to other fields, Asian Americans have made considerable contributions in science and technology in the United States, in such prominent innovative R&D regions as Silicon Valley and The Triangle.

Government and politics

Asian Americans have a high level of political incorporation in terms of their actual voting population. Since 1907, Asian Americans have been active at the national level and have had multiple officeholders at local, state, and national levels.

The highest ranked Asian American was Senator and President pro tempore Daniel Inouye, who died in office in 2012. There are several active Asian Americans in the United States Congress. With higher proportions and densities of Asian American populations, Hawaii has most consistently sent Asian Americans to the Senate, and Hawaii and California have most consistently sent Asian Americans to the House of Representatives.

Journalism

Connie Chung was one of the first Asian American national correspondents for a major TV news network, reporting for CBS in 1971. She later co-anchored the CBS Evening News from 1993 to 1995, becoming the first Asian American national news anchor.[101] At ABC, Ken Kashiwahara began reporting nationally in 1974. In 1989, Emil Guillermo, a Filipino American born reporter from San Francisco, became the first Asian American male to co-host a national news show when he was senior host at National Public Radio's "All Things Considered." In 1990, Sheryl WuDunn, a foreign correspondent in the Beijing Bureau of The New York Times, became the first Asian American to win a Pulitzer Prize. Ann Curry joined NBC News as a reporter in 1990, later becoming prominently associated with The Today Show in 1997. Carol Lin is perhaps best known for being the first to break the news of 9-11 on CNN. Dr. Sanjay Gupta is currently CNN's chief health correspondent. Lisa Ling, a former co-host on The View, now provides special reports for CNN and The Oprah Winfrey Show, as well as hosting National Geographic Channel's Explorer. Fareed Zakaria, a naturalised Indian-born immigrant, is a prominent journalist, and author specialising in international affairs. He is the editor-at-large of Time magazine, and the host of Fareed Zakaria GPS on CNN. Juju Chang, James Hatori, John Yang, Veronica De La Cruz, Michelle Malkin, Betty Nguyen, and Julie Chen have become familiar faces on television news. John Yang won a Peabody Award. Alex Tizon, a Seattle Times staff writer, won a Pulitzer Prize in 1997.

Military

Since the War of 1812 Asian Americans have served and fought on behalf of the United States. Serving in both segregated and non-segregated units until the desegregation of the US Military in 1948, 31 have been awarded the nation's highest award for combat valor, the Medal of Honor. Twenty-one of these were conferred upon members of the mostly Japanese American 100th Infantry Battalion of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team of World War II, the most highly decorated unit of its size in the history of the United States Armed Forces.[102][103]

Science and technology

Asian Americans have made many prominent and notable contributions to Science and Technology.

Chien-Shiung Wu was known to many scientists as the "First Lady of Physics" and played a pivotal role in experimentally demonstrating the violation of the law of conservation of parity in the field of particle physics. Fazlur Rahman Khan, also known as named as "The Father of tubular designs for high-rises",[104] was highlighted by President Barack Obama in a 2009 speech in Cairo, Egypt,[105] and has been called "Einstein of Structural engineering".[106] Min Chueh Chang was the co-inventor of the combined oral contraceptive pill and contributed significantly to the development of in vitro fertilisation at the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology. David T. Wong was one of the scientists credited with the discovery of ground-breaking drug Fluoxetine as well as the discovery of atomoxetine, duloxetine and dapoxetine with colleagues.[107][108][109] Michio Kaku has popularized science and has appeared on multiple programs on television and radio.

Award recipients

Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang received the 1957 Nobel Prize in Physics for theoretical work demonstrating that the conservation of parity did not always hold and later became American citizens. Har Gobind Khorana shared the 1968 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work in genetics and protein synthesis. Samuel Chao Chung Ting received the 1976 Nobel Prize in physics for discovery of the subatomic particle J/ψ. The mathematician Shing-Tung Yau won the Fields Medal in 1982 and Terence Tao won the Fields Medal in 2006. The geometer Shiing-Shen Chern received the Wolf Prize in Mathematics in 1983. Andrew Yao was awarded the Turing Award in 2000. Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar shared the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physics and had the Chandra X-ray Observatory named after him. In 1984, Dr. David D. Ho first reported the "healthy carrier state" of HIV infection, which identified HIV-positive individuals who showed no physical signs of AIDS. Charles J. Pedersen shared the 1987 Nobel Prize in chemistry for his methods of synthesizing crown ethers. Steven Chu shared the 1997 Nobel Prize in Physics for his research in cooling and trapping atoms using laser light. Daniel Tsui shared the 1998 Nobel Prize in Physics in 1998 for helping discover the fractional Quantum Hall effect. In 2008, biochemist Roger Tsien won the Nobel in Chemistry for his work on engineering and improving the green fluorescent protein (GFP) that has become a standard tool of modern molecular biology and biochemistry. Yoichiro Nambu received the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on the consequences of spontaneously broken symmetries in field theories. In 2009, Charles K. Kao was awarded Nobel Prize in Physics "for groundbreaking achievements concerning the transmission of light in fibres for optical communication" and Venkatraman Ramakrishnan won the prize in Chemistry "for studies of the structure and function of the ribosome". Ching W. Tang was the inventor of the Organic light-emitting diode and Organic solar cell and was awarded the 2011 Wolf Prize in Chemistry for this achievement. Manjul Bhargava, an American Canadian of Indian origins won the Fields Medal in mathematics in 2014. Shuji Nakamura won the 2014 Nobel Prize in Physics for the invention of efficient blue light-emitting diodes. Yitang Zhang is a Chinese-born American mathematician working in the area of number theory. While working for the University of New Hampshire as a lecturer, Zhang submitted an article to the Annals of Mathematics in 2013 which established the first finite bound on gaps between prime numbers, which lead to a 2014 MacArthur award.

Space

.jpg)

LTC Ellison Onizuka became the first Asian American (and third person of East Asian descent) when he made his first space flight aboard STS-51-C in 1985. Onizuka later died aboard the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1986. Taylor Gun-Jin Wang became the first person of Chinese ethnicity and first Chinese American, in space in 1985; he has since been followed by Leroy Chiao in 1994, and Ed Lu in 1997. In 1986, Franklin Chang-Diaz became the first Asian Latin American in space. Eugene H. Trinh became the first Vietnamese American in space in 1992. In 2001, Mark L. Polansky, a Jewish Korean American, made his first of three flights into space. In 2003, Kalpana Chawla became the first Indian American in space, but died aboard the ill-fated Space Shuttle Columbia. She has since been followed by CDR Sunita Williams in 2006.

Sports

Basketball

Wataru Misaka broke the NBA color barrier when he played for the New York Knicks in the 1947–48 season.[110] The next Asian American NBA player was Raymond Townsend, who played for the Golden State Warriors and Indiana Pacers from 1978 to 1982.[110] Rex Walters, played from 1993 to 2000 with the Nets, Philadelphia 76ers and Miami Heat;[110] he is presently the head coach for the University of San Francisco basketball team.[111] After playing basketball at Harvard University, point guard Jeremy Lin signed with the NBA's Golden State Warriors in 2010[110] and now plays for the Brooklyn Nets.

Current Kansas Jayhawks assistant coach Kurtis Townsend is Raymond Townsend's brother.[112]

Erik Spoelstra became the youngest coach ever in NBA history. He is currently the head coach of the Miami Heat.[113]

Football

In football, Wally Yonamine played professionally for the San Francisco 49ers in 1947.[114] Norm Chow is currently the head coach for the University of Hawaii and former offensive coordinator for UCLA after a short stint with the Tennessee Titans of the NFL, after 23 years of coaching other college teams, including four years as offensive coordinator at USC. In 1962, half Filipino Roman Gabriel was the first Asian American to start as an NFL quarterback. Dat Nguyen was an NFL middle linebacker who was an all-pro selection in 2003 for the Dallas Cowboys. In 1998, he was named an All-American and won the Bednarik Award as well as the Lombardi Award, while playing for Texas A&M University. Hines Ward who was born to a Korean mother and an African American father, is a former NFL wide receiver who was the MVP of Super Bowl XL and Ward also won the 12th season of the Dancing with the Stars television series. Former Patriot's linebacker Tedy Bruschi is of Filipino and Italian descent. While playing for the Patriots, Bruschi won three Super Bowl rings and was a two-time All-Pro selection. Bruschi is currently a NFL analyst at ESPN.

Mixed martial arts

There are several top ranked Asian American mixed martial artists. BJ Penn is a former UFC lightweight and welterweight champion. Cung Le is a former Strikeforce middleweight champion. Benson Henderson is the former WEC lightweight champion and a former UFC lightweight champion. Nam Phan is UFC featherweight fighter.

Olympics

Asian Americans first made an impact in Olympic sports in the late 1940s and in the 1950s. Sammy Lee became the first Asian American to earn an Olympic Gold Medal, winning in platform diving in both 1948 and 1952. Victoria Manalo Draves won both gold in platform and springboard diving in the 1948. Harold Sakata won a weightlifting silver medal in the 1948 Olympics, while Tommy Kono (weightlifting), Yoshinobu Oyakawa (100-meter backstroke), and Ford Konno (1500-meter freestyle) each won gold and set Olympic records in the 1952 Olympics. Konno won another gold and silver swimming medal at the same Olympics and added a silver medal in 1956, while Kono set another Olympic weightlifting record in 1956. Also at the 1952 Olympics, Evelyn Kawamoto won two bronze medals in swimming.

Amy Chow was a member of the gold medal women's gymnastics team at the 1996 Olympics; she also won an individual silver medal on the uneven bars. Gymnast Mohini Bhardwaj won a team silver medal in the 2004 Olympics. Bryan Clay who is of Half-Japanese descent[115] won the decathlon gold medal in the 2008 Olympics, the silver medal in the 2004 Olympics, and was the sport's 2005 world champion.

Since Tiffany Chin won the women's US Figure Skating Championship in 1985, Asian Americans have been prominent in that sport. Kristi Yamaguchi won three national championships, two world titles, and the 1992 Olympic Gold medal. Michelle Kwan has won nine national championships and five world titles, as well as two Olympic medals (silver in 1998, bronze in 2002).

Apolo Ohno, who is of half-Japanese descent,[116] is a short track speed skater and an eight-time Olympic medalist as well as the most decorated American Winter Olympic athlete of all time. He became the youngest U.S. national champion in 1997 and was the reigning champion from 2001 to 2009, winning the title a total of 12 times. In 1999, he became the youngest skater to win a World Cup event title, and became the first American to win a World Cup overall title in 2001, which he won again in 2003 and 2005. He won his first overall World Championship title at the 2008 championships.

Nathan Adrian, who is a hapa of half-Chinese descent,[117] is a professional American swimmer and three-time Olympic gold medalist who currently holds the American record in the 50 and 100-yard freestyle (short course) events. He has won a total of fifteen medals in major international competitions, twelve gold, two silver, and one bronze spanning the Olympics, the World, and the Pan Pacific Championships.

Other sports

Michael Chang was a top-ranked tennis player for most of his career, and the youngest ever winner of a Grand Slam tennis tournament in men's singles. He won the French Open in 1989. Tiger Woods, who is partially of Asian descent, is the most successful golfer of his generation and one of the most famous athletes in the world. Eric Koston is one of the top street skateboarders and placed first in the 2003 X-Games street competition. Richard Park is a Korean American ice hockey player who currently plays for the Swiss team HC Ambri-Piotta.

Brian Ching, whose father was Chinese, represented the United States Men's National Soccer Team, scoring 11 goals in 45 caps. He participated in the 2006 World Cup and won the 2007 Gold Cup.[118]

Julie Chu, who is three-quarter Chinese and one-quarter Puerto Rican,[119] is an American Olympic ice hockey player who played for the United States women's ice hockey team. She was also US Olympic Team Flag Bearer for the 2014 Winter Olympic Closing Ceremonies.[120]

Cultural influence

In recognition of the unique culture, traditions, and history of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, the United States government has permanently designated the month of May to be Asian Pacific American Heritage Month.[121][122]

Health and medicine

|

Asian immigrants are also changing the American medical landscape through increasing number of Asian medical practitioners in the United States. Beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, the US government invited a number of foreign physicians particularly from India and the Philippines to address the acute shortage of physicians in rural and medically underserved urban areas. The trend in importing foreign medical practitioners, however, became a long-term, chronic solution as US medical schools failed to produce enough physicians to match the increasing American population. Amid decreasing interest in medicine among American college students due to high educational costs and high rates of job dissatisfaction, loss of morale, stress, and lawsuits, Asian American immigrants maintained a supply of healthcare practitioners for millions of Americans. It is well documented that Asian American international medical graduates including highly skilled guest workers using the J1 Visa program for medical workers, tend to serve in health professions shortage areas (HPSA) and specialties that are not filled by US medical graduates especially primary care and rural medicine.[123][124] Thus, Asian American immigrants play a key role in averting a medical crisis in the US. A lasting legacy of Asian American involvement in medicine is the forcing of US medical establishment to accept minority medical practitioners. One could speculate that the introduction of Asian physicians and dentists to the American society could have triggered an acceptance of other minority groups by breaking down stereotypes and encouraging trust.[125] Traditional Asian concepts and practices in health and medicine have attracted greater acceptance and are more widely adopted by American doctors. India's Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine (which also includes acupuncture) are two alternative therapy systems that have been studied and adopted to a great extent. For instance, in the early 1970s the US medical establishment did not believe in the usefulness of acupuncture. Since then studies have proven the efficacy of acupuncture for different applications, especially for treatment of chronic pain.[126] It is now covered by many health insurance plans. Herbalism and massage therapy (from Ayurveda) are sweeping the spas across America. Meditation and yoga (from India) have also been widely adopted by health spas, and spiritual retreats of many religious bases. They are also part of the spiritual practice of the many Americans who are not affiliated with a mainline religious group. |

|

Education

| Ethnicity | High school graduation rate (2004) |

Bachelor's degree or higher (2010) |

|---|---|---|

| Filipinos | 90.8% | 48.1% |

| Indian | 90.2% | 70.7% |

| Pakistanis | 87.4% | 55.1% |

| Bangladeshis | 84.5% | 49.6% |

| Chinese | 80.8% | 51.8% |

| Japanese | 93.4% | 47.3% |

| Koreans | 90.2% | 52.9% |

| Vietnamese | 70.0% | 26.3% |

| Total U.S. population | 83.9% | 27.9% |

| Sources: 2004[130][131][132] and 2010[133] | ||

Among America's major racial categories, Asian Americans have the highest educational qualifications. This varies, however, for individual ethnic groups. Dr. C.N. Le, Director of the Asian & Asian American Studies Certificate Program at the University of Massachusetts, writes that although 42% of all Asian American adults have at least a college degree, Vietnamese Americans have a degree attainment rate of only 16% while Laotians and Cambodians only have rates around 5%.[134] It has been noted, however, that 2008 US Census statistics put the bachelor's degree attainment rate of Vietnamese Americans at 26%, which is not very different from the rate of 27% for all Americans.[135] According to the US Census Bureau in 2010, while the high school graduation rate for Asian Americans is on par with those of other ethnic groups, 50% of Asian Americans have attained at least a bachelor's degree as compared with the national average of 28%,[136] and 34% for non-Hispanic whites.[137] Indian Americans have some of the highest education rates, with nearly 71% having attained at least a bachelor's degree in 2010.[133] According to Carolyn Chen, director of the Asian American Studies Program at Northwestern University, as of December 2012 Asian Americans made up twelve to eighteen percent of the student population at Ivy League schools, larger than their share of the population.[138] For example, the Harvard Class of 2016 is 21% Asian American.[139]

In the years immediately preceding 2012, 61% of Asian American adult immigrants have a bachelor or higher level college education.[11]

Social and political issues

Illegal immigration

In 2012, there were 1.3 million alien Asian Americans; and for those awaiting visas, there were lengthy backlogs with over 450 thousand Filipinos, over 325 thousand Indians, over 250 thousand Vietnamese, and over 225 thousand Chinese are awaiting visas.[140][141] As of 2009, Filipinos and Indians accounted for the highest number of alien immigrants for "Asian Americans" with an estimated illegal population of 270,000 and 200,000 respectively. Indian Americans are also the fastest growing alien immigrant group in the United States, an increase in illegal immigration of 125% since 2000.[142][143] This is followed by Koreans (200,000) and Chinese (120,000).[144]

Due to the stereotype of Asian Americans being successful as a group and having the lowest crime rates in the United States, illegal immigration is mostly focused on those from Mexico and Latin America while leaving out Asians.[145] Asians are the second largest racial/ethnic alien immigrant group in the U.S. behind Hispanics and Latinos.[146][147] While the majority of Asian immigrants to the United States immigrate legally,[148] up to 15% of Asian immigrants immigrate without legal documents.[149]

Race-based violence

Asian Americans have been the target of violence based on their race and or ethnicity. This includes, but are not limited to, such events as the Rock Springs massacre,[150] Watsonville Riots,[151][152] attacks upon Japanese Americans following the attack on Pearl Harbor,[153] and Korean American businesses targeted during the 1992 Los Angeles riots.[154] According to historian Arif Dirlik: "Indian massacres of Chinese was a commonplace experience on the frontier, the most notable being the 'legendary slaughter by Paiute Indians of forty to sixty Chinese miners in 1866.'"[155] In the late 1980s, South Asians in New Jersey faced assault and other hate crimes by a group known as the Dotbusters.

After the September 11 attacks, Sikh Americans were targeted, being the recipient of numerous hate crimes including murder.[156][157][158][159] Other Asian Americans have also been the victim of race based violence in Brooklyn,[160] Philadelphia,[161][162] San Francisco,[163] and Bloomington, Indiana.[164] Furthermore, it has been reported that young Asian Americans are more likely to be a target of violence than their peers.[160][165][166] Racism and discrimination still persists against Asian Americans, occurring not only to recent immigrants but also towards well-educated and highly trained professionals.[167]

Recent waves of immigration of Asian Americans to largely African American neighborhoods have led to cases of severe racial tensions.[168] Acts of large-scale violence against Asian American students by their black classmates have been reported in multiple cities.[169][170][171] In October 2008, 30 black students chased and attacked 5 Asian students at South Philadelphia High School,[172] and a similar attack on Asian students occurred at the same school one year later, prompting a protest by Asian students in response.[173]

Asian-owned businesses have been a frequent target of tensions between black and Asian Americans. During the 1992 Los Angeles riots, more than 2000 Korean-owned businesses were looted or burned by groups of African Americans.[174][175][176] From 1990 to 1991, a high-profile, racially-motivated boycott of an Asian-owned shop in Brooklyn was organized by a local black nationalist activist, eventually resulting in the owner being forced to sell his business.[177] Another racially-motivated boycott against an Asian-owned business occurred in Dallas in 2012, after an Asian American clerk fatally shot an African American who had robbed his store.[178][179] During the Ferguson unrest in 2014, Asian-owned businesses were looted,[180] and Asian-owned stores were looted during the 2015 Baltimore protests while African-American owned stores were bypassed.[181] Violence against Asian Americans continue to occur based on their race,[182] with one source asserting that Asian Americans are the fastest growing targets of hate crimes and violence.[183]

Racial stereotypes

Until the late 20th century, the term "Asian American" was adopted mostly by activists, while the average person of Asian ancestries identified with their specific ethnicity.[184] The murder of Vincent Chin in 1982 was a pivotal civil rights case, and it marked the emergence of Asian Americans as a distinct group in United States.[184][185]

Stereotypes of Asians have been largely collectively internalized by society and these stereotypes have mainly negative repercussions for Asian Americans and Asian immigrants in daily interactions, current events, and governmental legislation. In many instances, media portrayals of East Asians often reflect a dominant Americentric perception rather than realistic and authentic depictions of true cultures, customs and behaviors.[186] Asians have experienced discrimination and have been victims of hate crimes related to their ethnic stereotypes.[187]

Study has indicated that most non-Asian Americans do not generally differentiate between Asian Americans of different ethnicities.[188] Stereotypes of Chinese Americans and Asian Americans are nearly identical.[189] A 2002 survey of Americans' attitudes toward Asian Americans and Chinese Americans indicated that 24% of the respondents disapprove of intermarriage with an Asian American, second only to African Americans; 23% would be uncomfortable supporting an Asian American presidential candidate, compared to 15% for an African American, 14% for a woman and 11% for a Jew; 17% would be upset if a substantial number of Asian Americans moved into their neighborhood; 25% had somewhat or very negative attitude toward Chinese Americans in general.[190] The study did find several positive perceptions of Chinese Americans: strong family values (91%); honesty as business people (77%); high value on education (67%).[189]

There is a widespread perception that Asian Americans are not "American" but are instead "perpetual foreigners".[190][191][192] Asian Americans often report being asked the question, "Where are you really from?" by other Americans, regardless of how long they or their ancestors have lived in United States and been a part of its society.[193] Many Asian Americans are themselves not immigrants but rather born in the United States. Many East Asian Americans are asked if they are Chinese or Japanese, an assumption based on major groups of past immigrants.[191][194]

Model minority

Asian Americans are sometimes characterized as a model minority in the United States because many of their cultures encourage a strong work ethic, a respect for elders, a high degree of professional and academic success, a high valuation of family, education and religion.[195][196] Statistics such as high household income and low incarceration rate,[197] low rates of many diseases and higher than average life expectancy[198] are also discussed as positive aspects of Asian Americans.

The implicit advice is that the other minorities should stop protesting and emulate the Asian American work ethic and devotion to higher education. Some critics say the depiction replaces biological racism with cultural racism, and should be dropped.[199] According to the Washington Post, "the idea that Asian Americans are distinct among minority groups and immune to the challenges faced by other people of color is a particularly sensitive issue for the community, which has recently fought to reclaim its place in social justice conversations with movements like #ModelMinorityMutiny."[200]

The model minority concept can also affect Asians' public education.[201] By comparison with other minorities, Asians often achieve higher test scores and grades compared to other Americans.[202] Stereotyping Asian American as over-achievers can lead to harm if school officials or peers expect all to perform higher than average.[203] The very high educational attainments of Asian Americans has often been noted; in 1980, for example, 74% of Chinese Americans, 62% of Japanese Americans, and 55% of Korean Americans aged 20–21 were in college, compared to only a third of the whites. The disparity at postgraduate levels is even greater, and the differential is especially notable in fields making heavy use of mathematics. By 2000, a plurality of undergraduates at such elite public California schools as UC Berkeley and UCLA, which are obligated by law to not consider race as a factor in admission, were Asian American. The pattern is rooted in the pre-World War II era. Native-born Chinese and Japanese Americans reached educational parity with majority whites in the early decades of the 20th century.[204]

The "model minority" stereotype fails to distinguish between different ethnic groups with different histories. When divided up by ethnicity, it can be seen that the economic and academic successes supposedly enjoyed by Asian Americans are concentrated into a few ethnic groups. Cambodians, Hmong, and Laotians (and to a lesser extent, Vietnamese), all of whose relatively low achievement rates are possibly due to their refugee status, and that they are non-voluntary immigrants;[205] additionally, one in five Hmong and Bangladeshi people live in poverty.[88]

Furthermore, the model minority concept can be emotionally damaging to some Asian Americans, particularly since they are expected to live up to those peers who fit the stereotype.[206] Studies have shown that some Asian Americans suffer from higher rates of stress, depression, mental illnesses, and suicides in comparison to other races,[207] indicating that the pressures to achieve and live up to the model minority image may take a mental and psychological toll on some Asian Americans.[208]

Bamboo ceiling

This concept appears to elevate Asian Americans by portraying them as an elite group of successful, highly educated, intelligent, and wealthy individuals, but it can also be considered an overly narrow and overly one-dimensional portrayal of Asian Americans, leaving out other human qualities such as vocal leadership, negative emotions, risk taking, ability to learn from mistakes, and desire for creative expression.[209] Furthermore, Asian Americans who do not fit into the model minority mold can face challenges when people's expectations based on the model minority myth do not match with reality. Traits outside of the model minority mold can be seen as negative character flaws for Asian Americans despite those very same traits being positive for the general American majority (e.g., risk taking, confidence, empowered). For this reason, Asian Americans encounter a "bamboo ceiling", the Asian American equivalent of the glass ceiling in the workplace, with only 1.5% of Fortune 500 CEOs being Asians, a percentage smaller than their percentage of the total United States population.[210]

The bamboo ceiling is defined as a combination of individual, cultural, and organisational factors that impede Asian Americans' career progress inside organizations. Since then, a variety of sectors (including nonprofits, universities, the government) have discussed the impact of the ceiling as it relates to Asians and the challenges they face. As described by Anne Fisher, the "bamboo ceiling" refers to the processes and barriers that serve to exclude Asians and American people of Asian descent from executive positions on the basis of subjective factors such as "lack of leadership potential" and "lack of communication skills" that cannot actually be explained by job performance or qualifications.[211] Articles regarding the subject have been published in Crains, Fortune magazine, and The Atlantic.[212][213][214]

Progress as a group within American society

Asian Americans have been making progress in American society. A key indicator is the salary of Asian Americans compared to other racial groups.

In 2015, the racial group with the highest earnings was Asian American men at $24/hour. Asian American men earned 117% as much as the reference group in the study (white American men at $21/hour) and have been the highest earning racial group since about 2000. Similarly, in 2015 Asian American women ($18/hour) was the highest earning female racial group and earned 106% as much as white American women ($17/hour). Asian American women have been the highest earning female group for more than 10 years in a row.[8]

By 2009, Asian surpassed Hispanics becoming the race with the highest immigration percentage into the United States. In 2010, they made up 36% of immigrants.[215]

Asian Americans are typically more involved in social media and the Internet. In a 2014 research study conducted by the Pew Research Center, 95% of English-speaking Asian Americans use the Internet—the highest of any other racial demographic by at least 8%.[216][217] Pew reported that Asian-Americans have been using the Internet more than any other group since as early as 2000.[217] Though the gap between Asian Americans and the other groups is decreasing, Asian Americans still have a comfortable lead.

Similarly, English speaking Asian Americans own smartphones more than any other group. They grew from 71% ownership in 2012 to 91% ownership in 2014. The next highest ownership percentage is 66% by Whites.[216] The Pew Research Center believes that two of the major reasons for the amazingly high ownership percentage are high levels of income and high levels of education.[218]

Similarly, 91% of English-speaking Asian Americans own a smartphone. Smartphone ownership among English-speaking Asian Americans has increased by 20 points in three years, from 71% in 2012 to 91% last year.[216] A related study shows that Asian Americans also lead in at home broadband service, sitting at 84%.[219]

Asian Americans are also very active on social media. On Instagram alone, they have several fashion bloggers who have millions of followers.[220]

For 2005, income statistics from US Census data are shown in the corresponding histogram figures.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Asian Americans. |

- Amerasian

- Asian Pacific American Heritage Month

- Asian American and Pacific Islander Policy Research Consortium

- Asian American studies

- Asian Americans in New York City

- Asian Hispanic and Latino Americans

- Asian Latino

- Asian Pacific American

- Asian pride

- Hyphenated American

- Jade Ribbon Campaign

- Index of Asian American-related articles

References

- ↑ "ACS DEMOGRAPHIC AND HOUSING ESTIMATES: 2015 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Most Children Younger Than Age 1 are Minorities, Census Bureau Reports – Population – Newsroom – U.S. Census Bureau". United States Census Bureau. May 17, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

"Cumulative Estimates of the Components of Resident Population Change by Race and Hispanic Origin for the United States: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2011 (NC-EST2011-04)". United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. May 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2013.18,205,898

"Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month: May 2013" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. March 27, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2013.18.2 million

The estimated number of U.S. residents in 2011 who were Asian, either alone or in combination with one or more additional races.

"Asian American/Pacific Islander Profile". Office of Minority Health. United States Department of Health & Human Services. September 17, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2013.According to the 2011 Census Bureau population estimate, there are 18.2 million Asian Americans, alone or in combination, living in the United States. Asian Americans account for 5.8 percent of the nation's population.

"Asian American Populations". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. United States Department of Health & Human Services. May 7, 2013. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved May 20, 2013.In 2011, the population of Asians, including those of more than one race, was estimated at 18.2 million in the U.S. population.

- ↑ "Supplemental Table 2. Persons Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident Status by Leading Core Based Statistical Areas (CBSAs) of Residence and Region and Country of Birth: Fiscal Year 2014". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Asian Americans: A Mosaic of Faiths". The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. Pew Research Center. July 19, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

Christian 42%, Buddhist 14%, Hindu 10%, Muslim 4%, Sikh 1%, Jain *% Unaffiliated 26%, Don't know/Refused 1%

- 1 2 Karen R. Humes; Nicholas A. Jones; Roberto R. Ramirez (March 2011). "Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- 1 2 3 U.S. Census Bureau, Census 2000 Summary File 1 Technical Documentation, 2001, at Appendix B-14. "A person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent including, for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam. It includes Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, and Other Asian."

- ↑ "U.S. Census Show Asians Are Fastest Growing Racial Group". NPR.org. Retrieved 2016-10-26.

- 1 2 3 Patten, Eileen. "Racial, gender wage gaps persist in U.S. despite some progress". Pew Research Center. Pew Research Center. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Educational Attainment in the United States: 2007" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. 2009.

- ↑ "Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2008" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. 2009. p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 Taylor, Paul; D'Vera Cohn; Wendy Wang; Jeffrey S. Passel; Rakesh Kochhar; Richard Fry; Kim Parker; Cary Funk; Gretchen M. Livingston; Eileen Patten; Seth Motel; Ana Gonzalez-Barrera (July 12, 2012). "The Rise of Asian Americans" (PDF). Pew Research Social & Demographic Trends. Pew Research Center. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ↑ White, Mercedes (January 23, 2013). "Asian-American population on the rise, Pew Research Center survey says". Deseret News. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Income and Poverty in the United States : 2014" (PDF). Census.gov. Retrieved 2017-02-27.

- ↑ Takei, Isao; Sakamoto, Arthur (2011-01-01). "Poverty among Asian Americans in the 21st Century". Sociological Perspectives. 54 (2): 251–276. JSTOR 10.1525/sop.2011.54.2.251. doi:10.1525/sop.2011.54.2.251.

- 1 2 K. Connie Kang (September 7, 2002). "Yuji Ichioka, 66; Led Way in Studying Lives of Asian Americans". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

Yet Ichioka created the first inter-ethnic pan-Asian American political group. And he coined the term "Asian American" to frame a new self-defining political lexicon. Before that, people of Asian ancestry were generally called Oriental or Asiatic.

- ↑ Mio, Jeffrey Scott, ed. (1999). Key Words in Multicultural Interventions: A Dictionary. ABC-Clio ebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 20. ISBN 9780313295478. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

The use of the term Asian American began in the late 1960s alongside the civil rights movement (Uba, 1994) and replaced disparaging labels of Oriental, Asiatic, and Mongoloid.

- ↑ "Proceedings of the Asiatic Exclusion League" Asiatic Exclusion League. San Francisco: April 1910. Pg. 7. "To amend section twenty-one hundred and sixty-nine of the Revised Statutes of the United States. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, that section twenty-one hundred and sixty-nine of the Revised Statutes of the United States be, and the same is hereby, amended by adding thereto the following: And Mongolians, Malays, and other Asiatics, except Armenians, Assyrians, and Jews, shall not be naturalized in the United States."

- ↑ How the U.S. Courts Established the White Race Archived August 11, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Chin, Gabriel J. (April 18, 2008). "The Civil Rights Revolution Comes to Immigration Law: A New Look at the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965". Rochester, New York: Social Science Research Network. SSRN 1121504

.

. - ↑ "Asian American". Oxford University Press. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ↑ "Asian". AskOxford.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2008. Retrieved September 29, 2007.

- ↑ Epicanthal folds: MedicinePlus Medical Encyclopedia states that "The presence of an epicanthal fold is normal in people of Asiatic descent" assuming it the norm for all Asians

- ↑ Kawamura, Kathleen (2004). "Chapter 28. Asian American Body Images". In Thomas F. Cash; Thomas Pruzinsky. Body Image: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice. Guilford Press. pp. 243–249. ISBN 978-1-59385-015-9.

- ↑ "American Community Survey; Puerto Rico Community Survey; 2007 Subject Definitions" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau: 31.

"American Community Survey; Puerto Rico Community Survey; 2007 Subject Definitions" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 11, 2011. - ↑ Cornell Asian American Studies Archived May 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.; contains mentions to South Asians

UC Berkeley – General Catalog – Asian American Studies Courses Archived December 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.; South and Southeast Asian courses are present

"Asian American Studies". 2009–2011 Undergraduate Catalog. University of Illinois at Chicago. 2009. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

"Welcome to Asian American Studies". Asian American Studies. California State University, Fullerton. 2003. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

"Program". Asian American Studies. Stanford University. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

"About Us". Asian American Studies. Ohio State University. 2007. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

"Welcome". Asian and Asian American Studies Certificate Program. University of Massachusetts Amherst. 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

"Overview". Cornell University Asian American Studies Program. Cornell University. 2007. Archived from the original on June 15, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2011. - ↑ "State & County QuickFacts: Race". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved August 31, 2009.

- ↑ "COMPARATIVE ENROLLMENT BY RACE/ETHNIC ORIGIN" (PDF). Diversity and Inclusion Office. Ferris State University. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

original peoples of Europe, North Africa, or the Middle East.

"Not Quite White: Race Classification and the Arab American Experience". Arab American Institute. Arab Americans by the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, Georgetown University. April 4, 1997. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

Ian Haney Lopez (1996). "How the U.S. Courts Established the White Race". Model Minority. New York University Press. Archived from the original on August 11, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

"Race". United States Census Bureau. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2010. Retrieved August 9, 2014.White. A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa. It includes people who indicate their race as "White" or report entries such as Irish, German, Italian, Lebanese, Arab, Moroccan, or Caucasian.

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau, 2000 Census of Population, Public Law 94-171 Redistricting Data File.Race at the Wayback Machine (archived November 3, 2001). (archived from the original on November 3, 2001).

- ↑ Kleinyesterday, Uri (2015-06-18). "New U.S. census category to include 'Israeli' option - Jewish World Features - Haaretz - Israel News". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 2017-02-27.

- ↑ "Public Comments Received on Federal Register notice 79 FR 71377 : Proposed Information Collection; Comment Request; 2015 National Content Test : U.S. Census Bureau; Department of Commerce : December 2, 2014 – February 2, 2015" (PDF). Census.gov. Retrieved 2017-02-27.

- ↑ 1980 Census: Instructions to Respondents, republished by Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Minnesota Population Center, University of Minnesota at http://www.ipums.org Accessed November 19, 2006.

- ↑ Lee, Gordon. Hyphen magazine. https://web.archive.org/web/20030707160800/http://www.hyphenmagazine.com/features/issues/summer03/theforgottenrevolution.php. Archived from the original on July 7, 2003. Retrieved June 1, 2016. Missing or empty

|title=(help). 2003. January 28, 2007 (archived from the original Archived October 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. on March 17, 2008). - ↑ Wu, Frank H. Wu (2003). Yellow: race in America beyond black and white. New York: Basic Books. p. 310. ISBN 9780465006403. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ↑ 1990 Census: Instructions to Respondents, republished by Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Minnesota Population Center, University of Minnesota at http://www.ipums.org Accessed November 19, 2006.

- ↑ Reeves, Terrance Claudett, Bennett. United States Census Bureau. Asian and Pacific Islander Population: March 2002. 2003. September 30, 2006.

- ↑ "Census Data / API Identities | Research & Statistics | Resources Publications Research Statistics | Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence". www.api-gbv.org. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ Wood, Daniel B. "Common Ground on who's an American." Christian Science Monitor. January 19, 2006. Retrieved February 16, 2007.

- ↑ "US Census Bureau, Asian Summary of Findings". Retrieved December 17, 2006.

- ↑ Searching For Asian America. Community Chats | PBS

- ↑ S. D. Ikeda. "What's an "Asian American" Now, Anyway?". Archived from the original on June 10, 2011.

- ↑ Yang, Jeff (October 27, 2012). "Easy Tiger (Nation)". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- 1 2 Han, Chong-Suk Winter (2015). Geisha of a Different Kind: Race and Sexuality in Gaysian America. New York: New York University Press. p. 4.

- ↑ Ono, Kent; Pham, Vincent (2009). Asian Americans and the Media. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- ↑ Chou, Rosalind (2012). Asian American Sexual Politics: The Construction of Race, Gender, and Sexuality. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- ↑ Barringer, Felicity (March 2, 1990). "Asian Population in U.S. Grew by 70% in the 80's". New York Times. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ Lowe, Lisa (2004). "Heterogeneity, Hybridity, Multiplicity: Marking Asian American Differences" (PDF). In Ono, Kent A. A Companion to Asian American Studies. Blackwell Companions in Cultural Studies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-4051-1595-7. Archived from the original on 1991. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ Skop, Emily; Li, Wei (2005). "Asians In America's Suburbs: Patterns And Consequences of Settlement". The Geographical Review. 95: 168.

- ↑ Fehr, Dennis Earl; Fehr, Mary Cain (2009). Teach boldly!: letters to teachers about contemporary issues in education. Peter Lang. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-4331-0491-6. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ↑ Raymond Arthur Smith (2009). "Issue Brief #160: Asian American Protest Politics: "The Politics of Identity"" (PDF). Majority Rule and Minority Rights Issue Briefs. Columbia University. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ↑ Wile, Rob (26 June 2016). "Latinos are no longer the fastest-growing racial group in America". Fusion. Doral, Florida. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month: May 2012". United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. March 21, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- 1 2 Timothy Pratt (October 18, 2012). "More Asian Immigrants Are Finding Ballots in Their Native Tongue". New York Times. Las Vegas. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ↑ Leslie Berestein Rojas (November 6, 2012). "Five new Asian languages make their debut at the polls". KPCC. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ↑ Shaun Tandon (January 17, 2013). "Half of Asian Americans rely on ethnic media: poll". Agence France-Presse. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ↑ Language Use and English-Speaking Ability: 2000: Census 2000 Brief

- ↑ EAC Issues Glossaries of Election Terms in Five Asian Languages Translations to Make Voting More Accessible to a Majority of Asian American Citizens. Election Assistance Commission. June 20, 2008. (archived from the original on July 31, 2008)

- ↑ "Asian Americans: A Mosaic of Faiths" (overview) (Archive). Pew Research. July 19, 2012. Retrieved on May 3, 2014.

- ↑ Leffel, Gregory P. Faith Seeking Action: Mission, Social Movements, and the Church in Motion. Scarecrow Press, 2007. ISBN 1461658578. p. 39

- ↑ Sawyer, Mary R. The Church on the Margins: Living Christian Community. A&C Black, 2003. ISBN 1563383667. p. 156

- ↑ "Historical Landmark, declared by the Filipino American National Historical Society, California Central Coast Chapter, Dedicated October 21, 1995". Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Historic Site, During the Manila". Michael L. Baird. Retrieved April 5, 2009.

- ↑ Eloisa Gomez Borah (1997). "Chronology of Filipinos in America Pre-1989" (PDF). Anderson School of Management. University of California, Los Angeles. Retrieved February 25, 2012.

Gonzalez, Joaquin (2009). Filipino American Faith in Action: Immigration, Religion, and Civic Engagement. NYU Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 9780814732977. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

Jackson, Yo, ed. (2006). Encyclopedia of Multicultural Psychology. SAGE. p. 216. ISBN 9781412909488. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

Juan Jr., E. San (2009). "Emergency Signals from the Shipwreck". Toward Filipino Self-Determination. SUNY series in global modernity. SUNY Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 9781438427379. Retrieved May 11, 2013. - ↑ Martha W. McCartney; Lorena S. Walsh; Ywone Edwards-Ingram; Andrew J. Butts; Beresford Callum (2003). "A Study of the Africans and African Americans on Jamestown Island and at Green Spring, 1619-1803" (PDF). Historic Jamestowne. National Park Service. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

Francis C.Assisi (May 16, 2007). "Indian Slaves in Colonial America". India Currents. Archived from the original on November 27, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2013. - ↑ Okihiro, Gary Y. (2005). The Columbia Guide To Asian American History. Columbia University Press. p. 178. ISBN 9780231115117. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Filipinos in Louisiana". Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- ↑ Wachtel, Alan (2009). Southeast Asian Americans. Marshall Cavendish. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-7614-4312-4. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ↑ John E. Van Sant (2000). Pacific Pioneers: Japanese Journeys to America and Hawaii, 1850-80. University of Illinois Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-252-02560-0.

- ↑ Sang Chi; Emily Moberg Robinson (January 2012). Voices of the Asian American and Pacific Islander Experience. ABC-CLIO. p. 377. ISBN 978-1-59884-354-5.

Joseph Nathan Kane (1964). Famous first facts: a record of first happenings, discoveries and inventions in the United States. H. W. Wilson. p. 161. - ↑ Wai-Jane Cha. "Chinese Merchant-Adventurers and Sugar Masters in Hawaii: 1802–1852" (PDF). University of Hawaii at Manoa. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ↑ Kalei, Kalikiano (August 12, 2010). "The Chinese Experience in Hawaii". University of Hawai`i Press. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ↑ Xiaojian Zhao; Edward J.W. Park Ph.D. (November 26, 2013). Asian Americans: An Encyclopedia of Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political History [3 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 357–358. ISBN 978-1-59884-240-1.

- ↑ Ronald Takaki, Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans (2nd ed. 1998) pp 133–78

- ↑ The Office of Multicultural Student Services (1999). "Filipino Migrant Workers in California". University of Hawaii. Archived from the original on December 4, 2014. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- ↑ Castillo, Adelaida (1976). "FILIPINO MIGRANTS IN SAN DIEGO 1900–1946". The Journal of San Diego History. San Diego Historical Society. 22 (3). Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- ↑ L. Scott Miller (1995). An American Imperative: Accelerating Minority Educational Advancement. Yale University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-300-07279-2.

- ↑ Chang, Iris (2003). The Chinese in America : a narrative history. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-03123-2.

- ↑ Richard T. Schaefer (March 20, 2008). Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society. SAGE Publications. p. 872. ISBN 978-1-4522-6586-5.

- ↑ Stephanie Hinnershitz-Hutchinson (May 2013). "The Legal Entanglements of Empire, Race, and Filipino Migration to the United States". Humanities and Social Sciences Net Online. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

Baldoz, Rick (2011). The Third Asiatic Invasion: Migration and Empire in Filipino America, 1898-1946. NYU Press. p. 204. ISBN 9780814709214. Retrieved August 7, 2014. - ↑ "Amazon.com: Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Politics and Society in Twentieth-Century America) eBook: Mae M. Ngai: Books". www.amazon.com. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ↑ Soodalter, Ron (2016). "By Soil Or By Blood". American History. 50.6: 56–63.

- ↑ Not including children of diplomats.

- ↑ Takaki, Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans (1998) pp 370–78

- ↑ "U.S. Immigration Legislation: 1917 Immigration Act". library.uwb.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-15.

- ↑ Franks, Joel (2015). "Anti-Asian Exclusion In The United States During The Nineteenth And Twentieth Centuries: The History Leading To The Immigration Act Of 1924". Journal of American Ethnic History. 34: 121–122.

- ↑ Takaki, Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans (1998) pp 197–211

- ↑ Elaine Howard Ecklund; Jerry Z. Park. "Asian American Community Participation and Religion: Civic "Model Minorities?"". Project MUSE. Baylor University. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jie Zong & Jeanne Batalova, Asian Immigrants in the United States, Migration Policy Institute (January 6, 2016).

- 1 2 3 Adams, Shar (May 3, 2012). "Growing Asian-American Communities Underrepresented". The Epoch Times. Archived from the original on December 15, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ↑ Semple, Kirk (January 8, 2013). "Asian-Americans Gain Influence in Philanthropy". New York Times. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

From 2000 to 2010, according to the Census Bureau, the number of people who identified themselves as partly or wholly Asian grew by nearly 46 percent, more than four times the growth rate of the overall population, making Asian-Americans the fastest growing racial group in the nation.

- ↑ Semple, Ken (18 June 2012). "In a Shift, Biggest Wave of Migrants Is Now Asian". New York Times. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

"New Asian 'American Dream': Asians Surpass Hispanics in Immigration". ABC News. United States News. 19 June 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

Jonathan H. X. Lee (16 January 2015). History of Asian Americans: Exploring Diverse Roots: Exploring Diverse Roots. ABC-CLIO. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-313-38459-2. - ↑ Rivitz, Jessica (28 September 2015). "Asians on pace to overtake Hispanics among U.S. immigrants, study shows". CNN. Atlanta. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ↑ Erika Lee, Chinese immigrants now largest group of new arrivals to the U.S., USA Today (July 7, 2015).

- ↑ Rhea, Joseph Tilden (May 1, 2001). Race Pride and the American Identity. Harvard University Press. p. 43. ISBN 9780674005761.

- ↑ We Are Siamese Twins-Fai的分裂生活 Archived December 22, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Lee, Elizabeth (February 28, 2013). "YouTube Spawns Asian-American Celebrities". VAO News. Archived from the original on February 18, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ↑ Chow, Kat (February 5, 2015). "A Brief, Weird History Of Squashed Asian-American TV Shows". NPR. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

Cruz, Lenika (February 4, 2015). "Why There's So Much Riding on Fresh Off the Boat". The Atlantic. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

Gamboa, Glenn (January 30, 2015). "Eddie Huang a fresh voice in 'Fresh Off the Boat'". Newsday. Long Island, New York. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

Lee, Adrian (February 5, 2015). "Will Fresh Off The Boat wind up being a noble failure?". MacLeans. Canada. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

Oriel, Christina (December 20, 2014). "Asian American sitcom to air on ABC in 2015". Asian Journal. Los Angeles. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

Beale, Lewis (February 3, 2015). "The Overdue Asian TV Movement". The Daily Beast. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

Yang, Jeff (May 2, 2014). "Why the 'Fresh Off the Boat' TV Series Could Change the Game". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

Joann Faung Jean Lee (August 1, 2000). Asian American Actors: Oral Histories from Stage, Screen, and Television. McFarland. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-7864-0730-9.

Branch, Chris (February 5, 2015). "'Fresh Off The Boat' Brings Asian-Americans To The Table On Network TV". Huffington Post. Retrieved February 8, 2015. - ↑ Chin, Justin. Elledge, Jim, and David Groff, eds. "Some Notes, Thoughts, Recollections, Revisions, and Corrections Regarding Becoming, Being, and Remaining a Gay Writer". Who's Yer Daddy?: Gay Writers Celebrate Their Mentors and Forerunners. 1 edition. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press, 2012. Print. P. 55

- ↑ "100 Most Successful Asian American Entrepreneurs".

- ↑ "Broad racial disparities persist". Archived from the original on November 30, 2006. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- ↑ "Notable Asian American Professionals".

- ↑ "CONNIE CHUNG". World Changers. Portland State University. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved February 21, 2012.