Sophie Taeuber-Arp

| Sophie Taeuber-Arp | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Sophie Henriette Gertrude Taeuber 19 January 1889 Davos Platz, Switzerland |

| Died |

13 January 1943 (aged 53) Zürich-Höngg, Switzerland |

| Resting place | Davos, Trogen, Munich, Hamburg, Zurich, Strasbourg, Paris, Grasse |

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Education | Gewerbeschule in St. Gallen, Dschebitz-Schule in Munich, and Kunstgewerbeschule in Hamburg |

| Known for | Sculpture, painting, textile design, dancing |

| Movement | Concrete Art, Constructivism, Dada |

| Spouse(s) | Hans Arp |

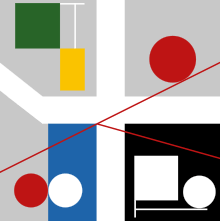

Sophie Henriette Gertrude Taeuber-Arp (/ˈtɔɪbər ˈɑːrp/; 19 January 1889 – 13 January 1943) was a Swiss artist, painter, sculptor, textile designer, furniture and interior designer, architect and dancer. She is considered one of the most important artists of concrete art and geometric abstraction of the 20th century.

Early life

Born in Davos, Switzerland, Sophie Henriette Gertrude Taeuber was the fifth child of Prussian pharmacist Emil Taeuber and Swiss Sophie Taeuber-Krüsi, from Gais in Appenzell Inner Rhodes, Switzerland. Her parents operated a pharmacy in Davos until her father died of tuberculosis when she was two years old, after which the family moved to Trogen, where her mother opened a pension. She studied textile design at the trade school (Gewerbeschule, today School of Applied Arts) in St. Gallen (1906–1910).[1] She then moved on to the workshop of Wilhelm von Debschitz at his school in Munich, where she studied in 1911 and again in 1913; in between, she studied for a year at the School of Arts and Crafts (Kunstgewerbeschule) in Hamburg. She joined the Schweizerischer Werkbund in 1915.[2] In the same year, she attended the Laban School of Dance in Zurich, and in the summer she joined the artist colony of Monte Verita in Ascona; in 1917, she danced with Suzanne Perrottet, Mary Wigman and others at the Sun Festival organised by Laban in Ascona.[3]

Dada

In 1915, at an exhibition at the Tanner Gallery, she met the Dada artist Jean "Hans" Arp, who had moved to Zurich in 1915 to avoid being drafted by the German Army during the First World War.[2] They were to collaborate on numerous joint projects until her death in 1943. They married in 1922 and she changed her last name to Taeuber-Arp.[4]

Taeuber-Arp taught weaving and other textile arts at the Zurich Kunstgewerbeschule (now Zurich University of the Arts) from 1916 to 1929. Her textile and graphic works from around 1916 through the 1920s are among the earliest Constructivist works, along with those of Piet Mondrian and Kasimir Malevich. These sophisticated geometric abstractions reflect a subtle understanding of the interplay between colour and form.[1]

During this period, she was involved in the Zürich Dada movement, which centred on the Cabaret Voltaire.[1] She took part in Dada-inspired performances as a dancer, choreographer, and puppeteer, and she designed puppets, costumes and sets for performances at the Cabaret Voltaire as well as for other Swiss and French theatres. At the opening of the Galerie Dada in 1917, she danced to poetry by Hugo Ball while wearing a shamanic mask by Marcel Janco. A year later, she was a co-signer of the Zurich Dada Manifesto.[5]

She also made a number of sculptural works, such as a set of abstract "Dada Heads" of turned polychromed wood. With their witty resemblance to the ubiquitous small stands used by hatmakers, they typified her elegant synthesis of the fine and applied arts.[6]

Tauber-Arp was also close friends and contemporaries with the French-Romanian avant-garde poet, essayist, and artist, Tristan Tzara, one of the central figures of the Dada movement. In 1920, Tzara solicited over four dozen Dadaist artists, among which were Tauber-Arp, Jean Arp, Jean Cocteau, Marcel DuChamp, and Hannah Hoch. Tzara planned to use the contributed text and images to create an anthology of Dada work entitled Dadaglobe. A worldwide release of 10,000 copies was planned, but the project was abandoned when its main backer, Francis Picabia, distanced himself from Tzara in 1921.[7]

France

In 1926 Taeuber-Arp and Jean Arp moved to Strasbourg, where both took up French citizenship; after which they divided their time between Strasbourg and Paris. There Taeuber-Arp received numerous commissions for interior design projects; for example, she was commissioned to create a radically Constructivist interior for the Café de l'Aubette – a project on which Jean Arp and de Stijl artist Theo van Doesburg eventually joined her as collaborators. In 1927 she co-authored a book entitled Welly Lowell with Blanche Gauchet.[4]

From the late 1920s, she lived mainly in Paris and continued experimenting with design. The couple became French citizens in 1926[2] and in 1928 they moved to Meudon-Val Fleury, outside Paris, where she designed their new house and some of its furnishings.[8] She was an exhibitor at the Salon des Surindépendents in Paris in 1929–30.

In the 1930s, she was a member of the group Cercle et Carré, founded by Michel Seuphor and Joaquín Torres García as a standard-bearer of non-figurative art, and its successor, the Abstraction-Création group (1931-4).[2] Later in the decade she founded a Constructivist review, Plastique (Plastic) in Paris. Her circle of friends included the artists Sonia Delaunay, Robert Delaunay, Wassily Kandinsky, Joan Miró, and Marcel Duchamp.[4] She was also a member of Allianz, a union of Swiss painters, from 1937-43.[2] In 1940, Taeuber-Arp and Arp fled Paris ahead of the Nazi occupation and moved to Grasse in Vichy France, where they created an art colony with Sonia Delaunay, Alberto Magnelli, and other artists. At the end of 1942, they had to flee to Switzerland. In early 1943, Taeuber-Arp died of accidental carbon monoxide poisoning due to a malfunctioning stove at the house of Max Bill.[4]

In 2014, at the Danser sa vie dance and art exhibition at the Centre Georges Pompidou in France, a photograph was displayed of Tauber-Arp dancing in a highly-stylized mask and costume at the Cabaret Voltaire in 1917.[9]

Legacy

Taeuber-Arp is the only woman on the current series of Swiss banknotes in Switzerland; her portrait has been on the 50-franc note since 1995.[4]

A museum honouring[10] Taeuber-Arp and Jean Arp opened in 2007 in a section of the Rolandseck railway station in Germany, re-designed by Richard Meier.[4] The video work "Sophie Taeuber-Arp's Vanishing Lines" (2015) by new media artist Myriam Thyes from Switzerland is about her "Lignes" drawings, segmented circles intersected by lines.[11][12]

Exhibitions

Taeuber-Arp took part in numerous exhibitions. For example, she was included in the first Carré exhibition at the Galeries 23 (Paris) in 1930, along with other notable early 20th-century modernists. Many museums around the world have her work in their collections, but in the public consciousness her reputation lagged for many years behind that of her more famous husband. Sophie Taeuber-Arp began to gain substantial recognition only after the Second World War, and her work is now generally accepted as in the first rank of classical modernism. An important milestone was the exhibition of her work at documenta 1 in 1955.

In 1970, an exhibit of Tauber-Arp's work was shown at the Albert Loeb Gallery in New York City.[13]

Then, in 1981 the Museum of Modern Art (New York) mounted a retrospective of her work that subsequently travelled to the Museum of Contemporary Art (Chicago), the Museum of Fine Arts (Houston), Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal.[4]

American scholar, Adrian Sudhalter, organized an exhibition called "Dadaglobe Reconstructed" that sought to honor the centennial of Dada's inception, along with Tzara's ambitious project. Compiling over 100 works of art that were initially slated to appear in Tristan Tzara's Dadaglobe anthology, among which are works by Tauber-Arp, the show ran from 5 February to 1 May 2016 at the Kunsthaus Zurich, and from 12 June to 18 September 2016 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.[14]

Honour

On 19 January 2016, Google created a Google Doodle for Sophie to commemorate her 127th birthday. The doodle was made by Mark Holmes, who describes Tauber-Arp as "such a prolific and diverse artist." [15][16][17]

Bibliography

- Andreas Kotte, ed. (2005). "Sophie Taeuber-Arp". Theaterlexikon der Schweiz (TLS) / Dictionnaire du théâtre en Suisse (DTS) / Dizionario Teatrale Svizzero / Lexicon da teater svizzer [Theater Dictionary of Switzerland]. 3. Zürich: Chronos. pp. 1787/1788. ISBN 978-3-0340-0715-3. LCCN 2007423414. OCLC 62309181.

- Sophie Taeuber-Arp 1889-1943. Catalogue of the exhibition in the Arp-Museum Bahnhof Rolandseck, at the Kunsthalle Tübingen (1993), at the Städtischen Galerie im Lenbachhaus München (1994). publisher: Siegfried Gohr, Verlag Gerd Hatje, Stuttgart, 1993. ISBN 3-7757-0419-1

- Gabriele Mahn: "Sophie Taeuber-Arp", pp. 160–168, in: Karo Dame, book on the exhibition Karo Dame. Konstruktive, Konkrete und Radikale Kunst von Frauen von 1914 bis heute, Aargauer Kunsthaus Aarau, publisher: Beat Wismer, Verlag Lars Müller, Baden, 1995. ISBN 3-906700-95-X

- Christoph Vögele. Variations. Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Arbeiten auf Papier. Book on the exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Solothurn. Heidelberg: Kehrer Verlag, 2002. ISBN 3-933257-90-5

- Sophie Taeuber-Arp – Gestalterin, Architektin, Tänzerin. Catalogue of the exhibition at the Museum Bellerive, Zürich. publisher: Hochschule für Gestaltung und Kunst Zürich. Zürich: Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess, 2007. ISBN 978-3-85881-196-7

- Bewegung und Gleichgewicht. Sophie Taeuber-Arp 1889-1943. Book on the exhibition at the Kirchner Museum Davos and at the Arp Museum Bahnhof Rolandseck. editor: Karin Schick, Oliver Kornhoff, Astrid von Asten. Bielefeld: Kerber Verlag, 2010. ISBN 978-3-86678-320-1

- Susanne Meyer-Büser: "Zwei Netzwerkerinnen der Avantgarde in Paris um 1930. Auf den Spuren von Florence Henri und Sophie Taeuber-Arp", in: Die andere Seite des Mondes. Künstlerinnen der Avantgarde. Book on the exhibition at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf (ed.), and at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Dänemark. Köln: DuMont Buchverlag, 2011. ISBN 978-3-8321-9391-1

- Roswitha Mair: Handwerk und Avantgarde. Das Leben der Künstlerin Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Berlin: Parthas Verlag, 2013. ISBN 978-3-86964-047-1

- Sophie Taeuber-Arp – Heute ist Morgen. Comprehensive publication on the exhibition at the Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aarau, and at the Kunsthalle Bielefeld. Editor: Thomas Schmutz und Aargauer Kunsthaus, Friedrich Meschede und Kunsthalle Bielefeld. Zurich: Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess, 2014. ISBN 978-3-85881-432-6

- West, Shearer (1996). The Bullfinch Guide to Art. UK: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 0-8212-2137-X.

- Schmidt, Georg, ed. (1948). Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Holbein Verlag.

- Vgele, Christoph, and Walburga Krupp (2003). Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Works on Paper, Kehrer Verlag.

References

- 1 2 3 Schelbert, Leo (21 May 2014). Historical Dictionary of Switzerland. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 369. ISBN 978-1-4422-3352-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gaze, Delia (2013). Concise Dictionary of Women Artists. Routledge. pp. 651–3. ISBN 978-1-136-59901-9.

- ↑ Arp, Jean; Hancock, Jane; Poley, Stefanie (1987). Arp, 1886-1966. Hatje. p. 286.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Roswitha Mair (2013). Handwerk und Avantgarde. Das Leben der Künstlerin Sophie Taeuber-Arp (in German). Parthas Verlag Berlin. ISBN 978-3-86964-047-1.

- ↑ Pappas, Theoni (1999). Mathematical footprints: discovering mathematical impressions all around us. Wide World Publishing/Tetra. p. 127.

- ↑ Blistène, Bernard; Dennison, Lisa (1998). Rendezvous: Masterpieces from the Centre Georges Pompidou and the Guggenheim Museums. Guggenheim Museum Publications. p. 695. ISBN 978-0-8109-6916-2.

- ↑ Farago, Jason (2016-06-16). "A Plan to Spread Dada Worldwide, Revisited at MoMA". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- ↑ Saskia de Rothschild (February 14, 2013), Glimpses of Jean Arp’s World New York Times.

- ↑ "Dada Dance: Sophie Taeuber’s Visceral Abstraction - Art Journal Open". Art Journal Open. 2014-07-03. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- ↑ arp museum. "Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp". Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ↑ schaumbad Atelier Graz. "100 Years of World Transition". Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ↑ Myriam Thyes. "Sophie Taeuber-Arp's Vanishing Lines". Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ↑ Kramer, Hilton. "Taeuber‐Arp and Albers: Loyal Only to Art - NYTimes.com". Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- ↑ "Dadaglobe Reconstructed | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- ↑ Parsons, Jeff (2016-01-19). "Who was Sophie Taeuber-Arp and why is she the subject of today's Google doodle?". mirror. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- ↑ Rhiannon Williams (19 January 2016). "Who was Sophie Taeuber-Arp? One of the most influential female artists you've probably never heard of". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ↑ "Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s 127th Birthday". google.com.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sophie Taeuber-Arp. |

- Taeuber-Arp collection at Museum of Modern Art

- Sophie Taeuber-Arp in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website