Sonnet 2

| Sonnet 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

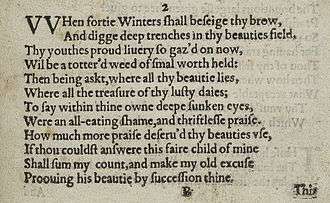

The first twelves lines of Sonnet 2 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 2 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a procreation sonnet within the Fair Youth sequence.

Synopsis

When forty winters shall besiege thy brow,

- when forty winters {many years} had come, and the traces of it shows on your brows, which is forehead which may imply that the user will have a lot of wrinkles

And dig deep trenches in thy beauty's field,

- his beauty will not last, {dig deep trenches} meaning die/grave

Thy youth's proud livery, so gazed on now,

- his youth, which is very much desired {so-gazed on now}

Will be a tatter'd weed, of small worth held:

- his youth will no longer worth anything, not desirable anymore, just like a piece of damaged/tore clothes/garments

Then being ask'd where all thy beauty lies,

- people will ask where his beauty is

Where all the treasure of thy lusty days,

- {lusty days} meaning young, {treasure} meaning when we're young we have strength, beauty and happiness

To say, within thine own deep-sunken eyes,

- he will reply the people who'd asked him where his beauty is that it still lies in his {deep-sunken eyes ; face that looks like a skull ; which is the attributes of old people] eyes

Were an all-eating shame and thriftless praise.

- the user should be ashamed of himself, because he is throwing praises on himself like a {thriftless} person who spends more than what he has

How much more praise deserved thy beauty's use,

- he will be praised by using his {beauty- because of his looks, he can have all those lusty and vigorous days, and he can use it} to reproduce and pass it down

If thou couldst answer 'This fair child of mine

- {this fair child of mine} meaning reproduce a child, passing down all this beauty to his child, thus, people will praise him a lot if he uses his beauty {his looks, and because he had the looks, he can have all those lusty and vigorous days} to reproduce a child.

Shall sum my count and make my old excuse,

- {shall sum my count - which links back to 'thriftless' in the poem} {make my old excuse - when a person ask where did his beauty go, he can use his child and say he had passed it all down to his children} it means that he can use his child to bear all the praise that he had when he was young {because linking back to thriftless, he threw all the praise on himself for being young and beautiful instead of being old, and thus shall sum my count", his child can bear all his praise for him, and can also use his child to answer somebody if they ask about the whereabouts of his beauty.

Proving his beauty by succession thine!

- his child can prove that the user is beautiful when he was young to the other people that said or think that the user should be ashamed of himself where he is not beautiful but he kept saying he was beautiful, to sum it up, having a child can show or continue his line of beauty, getting praise once more.

This were to be new made when thou art old,

- his beauty can be re-born again when he grows old, by having a child to inherit his beautifulness

And see thy blood warm when thou feel'st it cold.

- if the user is old and his blood is cold, when he look at his child whom his beauty had been passed down to, he will feel young and warm again.[citation needed]

Structure

Sonnet 2 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet, which consists of three quatrains followed by a couplet. It follows the form's typical rhyme scheme: abab cdcd efef gg. Like all but one sonnet in the sequence, it is written in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions:

× / × / × / × / × / How much more praise deserved thy beauty's use, (2.9)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Detailed analysis

Shakespeare's Sonnet 2 is another procreation sonnet and inquiry into Time's destruction of Beauty, urging the young man of the sonnet to have a child. The youth’s “proud liuery” is the costume in which he is dressed or that which identifies him as youth.[2] The only way for the youth's beauty to be preserved is to have a child. Therefore, when the man described is old, his heir will be young — "This were to be new made when thou art old." The theme of necessary procreation found in Sonnet 1 continues into Sonnet 2. The man's beauty will be lost and become like a "tattered weed." "Will be a tatter'd weed, of small worth held" unless he reproduces. People will ask where his beauty is "Then being ask'd where all thy beauty lies."

Sonnet 2 is also a working of the standard ‘siege’ conceit found in many sonnets. Forty winters will “digge deep trenches;” trenches were dug during sieges. Trenches are formed also when a field is ploughed, and metaphorically are wrinkles etched in a brow. The image was traditional from classical times, from Virgil (‘he ploughs the brow with furrows’) and Ovid (‘furrows which may plough your body will come already’) to Shakespeare’s contemporary, Drayton, “The time-plow’d furrowes in thy fairest field.” The primary meaning of “field” is a battlefield where a siege might occur, but it retains its agricultural or husbandry sense, taken up later in “weed,” and is also an heraldic term for the surface of an escutcheon or shield, on which a “charge” is imposed. The colours of a servant’s “liuery” were those of an armorial shield’s field and principal charge, so the royal liuery is scarlet trimmed with gold.[2]

Interpretations

- Caroline Blakiston, for the 2002 compilation album, When Love Speaks (EMI Classics)

References

- ↑ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- 1 2 Larsen, Kenneth. "Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets". Sonnet 2. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

Further reading

- Baldwin, T. W. On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1950.

- Hubler, Edwin. The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

Works related to Sonnet 2 at Wikisource

Works related to Sonnet 2 at Wikisource- An analysis of the sonnet

- An analysis and paraphrase of the sonnet

.png)