Sonnet 18

| Sonnet 18 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

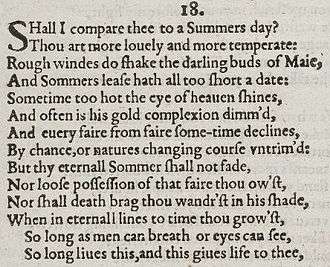

Sonnet 18 in the 1609 Quarto of Shakespeare's sonnets | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 18, often alternatively titled Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?, is one of the best-known of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. Part of the Fair Youth sequence (which comprises sonnets 1–126 in the accepted numbering stemming from the first edition in 1609), it is the first of the cycle after the opening sequence now described as the procreation sonnets.

In the sonnet, the speaker asks whether or not he should compare his beloved to the summer season, and argues that he should not because the comparison does not properly express the depths of his emotion. He also states that his beloved will live on forever through the words of the poem. Scholars have found parallels within the poem to Ovid's Tristia and Amores, both of which have love themes. Sonnet 18 is written in the typical Shakespearean sonnet form, having 14 lines of iambic pentameter ending in a rhymed couplet. Detailed exegeses have revealed several double meanings within the poem, giving it a greater depth of interpretation.

Paraphrase

The poem starts with a flattering question to the beloved—"Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?" The beloved is "more lovely and more temperate" than a summer's day. The speaker lists some negative things about summer: it is short—"summer's lease hath all too short a date"—and sometimes the sun is too hot—"Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines." However, the beloved has beauty that will last forever, unlike the fleeting beauty of a summer's day. By putting his love's beauty into the form of poetry, the poet is preserving it forever. "So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee." The lover's beauty will live on, through the poem which will last as long as it can be read.

Structure

Sonnet 18 is a typical English or Shakespearean sonnet. It consists of three quatrains followed by a couplet, and it has the characteristic rhyme scheme: abab cdcd efef gg. The poem reflects the rhetorical tradition of an Italian or Petrarchan Sonnet. Petrarchan sonnets typically discussed the love and beauty of a beloved, often an unattainable love, but not always.[2] It also contains a volta, or shift in the poem's subject matter, beginning with the third quatrain.[3]

The couplet's first line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter rhythm:

× / × / × / × / × / So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, (18.13)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Context

The poem is part of the Fair Youth sequence (which comprises sonnets 1–126 in the accepted numbering stemming from the first edition in 1609). It is also the first of the cycle after the opening sequence now described as the procreation sonnets. Some scholars, however, contend that it is part of the procreation sonnets, as it addresses the idea of reaching eternal life through the written word, a theme they find in sonnets 15–17. In this view, it can be seen as part of a transition to sonnet 20's time theme.[4]

There are many, varying theories about the identity of the 1609 Quarto's enigmatic dedicatee, Mr. W.H. Some scholars have suggested that this poem may be expressing a hope that they interpret the procreation sonnets as having despaired of: the hope of metaphorical procreation in a homosexual relationship.[5] Professor Michael Schoenfeldt of the University of Michigan, characterizes the Fair Youth sequence sonnets as "the articulation of a fervent same-sex love,"[6] and some scholars, noting the romantic language used in the sequence, refer to it as a "daring representation of homoerotic...passions," [7] of "passionate, erotic love," [8] suggesting that the relationship between the speaker and the Fair Youth is sexual. The true character of this love remains unclear, however, and others interpret the relationship as one of purely platonic love, while yet others see it as describing a woman. Scholars have pointed out that the order in which the sonnets are placed may have been the decision of the publishers, and not of Shakespeare, which would further support the interpretation that Sonnet 18 was addressed to a woman.[9]

Exegesis

Line one is paradoxical, because the implied answer to the poet's question, "Shall I compare thee to a summer's day", is in the negative, even though the point is illustrated by comparisons.[10]

"Complexion" in line six, can have two meanings: 1) The outward appearance of the face as compared with the sun ("the eye of heaven") in the previous line, or 2) the older sense of the word in relation to The four humours. In Shakespeare's time, "complexion" carried both outward and inward meanings, as did the word "temperate" (externally, a weather condition; internally, a balance of humours). The second meaning of "complexion" would communicate that the beloved's inner, cheerful, and temperate disposition is constant, unlike the sun, which may be blotted out on a cloudy day. The first meaning is more obvious, meaning of a negative change in his outward appearance.[11]

The word, "untrimmed" in line eight, can be taken two ways: First, in the sense of loss of decoration and frills, and second, in the sense of untrimmed sails on a ship. In the first interpretation, the poem reads that beautiful things naturally lose their fanciness over time. In the second, it reads that nature is a ship with sails not adjusted to wind changes in order to correct course. This, in combination with the words "nature's changing course", creates an oxymoron: the unchanging change of nature, or the fact that the only thing that does not change is change. This line in the poem creates a shift from the mutability of the first eight lines, into the eternity of the last six. Both change and eternity are then acknowledged and challenged by the final line.[2]

"Ow'st" in line ten can also carry two meanings equally common at the time: "ownest" and "owest". Many readers interpret it as "ownest", as do many Shakespearean glosses ("owe" in Shakespeare's day, was sometimes used as a synonym for "own"). However, "owest" delivers an interesting view on the text. It conveys the idea that beauty is something borrowed from nature—that it must be paid back as time progresses. In this interpretation, "fair" can be a pun on "fare", or the fare required by nature for life's journey.[12] Other scholars have pointed out that this borrowing and lending theme within the poem is true of both nature and humanity. Summer, for example, is said to have a "lease" with "all too short a date." This monetary theme is common in many of Shakespeare's sonnets, as it was an everyday theme in his budding capitalistic society.[13]

Notes

- ↑ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201. To correct a typographical error in Arden 1, Quatrain 2 has been supplied by Arden 3: Duncan-Jones, Katherine (1997). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: Arden Shakespeare. ISBN 978-1903436578.

- 1 2 Jungman, Robert E. (January 2003). "Trimming Shakespeare's Sonnet 18.". ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews. ANQ. 16 (1): 18–19. ISSN 0895-769X. doi:10.1080/08957690309598181.

- ↑ Preminger, Alex and T. Brogan. The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993. pg. 894 ISBN 0-691-02123-6

- ↑ Shakespeare, William et al. The Sonnets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. pg. 130 ISBN 0-521-29403-7

- ↑ Neely, Carol Thomas (October 1978). "The Structure of English Renaissance Sonnet Sequence". ELH. ELH, Vol. 45, No. 3. 45 (3): 359–389. JSTOR 2872643. doi:10.2307/2872643.

- ↑ Schoenfeldt, Michael Carl. A Companion to Shakespeare's Sonnets. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2010. Print. p 1.

- ↑ (Cohen 1745)

- ↑ (Cohen 1749)

- ↑ Schiffer, James. Shakespeare's Sonnets. New York: Garland Pub, 1999. pg. 124. ISBN 0-8153-2365-4

- ↑ Larsen, Kenneth J. "Sonnet 18". Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ↑ Ray, Robert H. (October 1994). "Shakespeare's Sonnet 18.". The Explicator. 53 (1): 10–11. ISSN 0014-4940. doi:10.1080/00144940.1994.9938800.

- ↑ Howell, Mark (April 1982). "Shakespeare's Sonnet 18". The Explicator. 40 (3): 12. ISSN 0014-4940.

- ↑ Thurman, Christopher (May 2007). "Love's Usury, Poet's Debt: Borrowing and Mimesis in Shakespeare's Sonnets". Literature Compass. Literature Compass. 4 (3): 809–819. doi:10.1111/j.1741-4113.2007.00433.x.

References

- Baldwin, T. W. (1950). On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- Hubler, Edward (1952). The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Schoenfeldt, Michael (2007). The Sonnets: The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare’s Poetry. Patrick Cheney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

Works related to Sonnet 18 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource

Works related to Sonnet 18 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource- Paraphrase and analysis (Shakespeare-online)

- David Gilmour's recording of Sonnet 18 on YouTube

- Poeterra's recording of Sonnet 18

.png)