Sonnet 131

| Sonnet 131 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

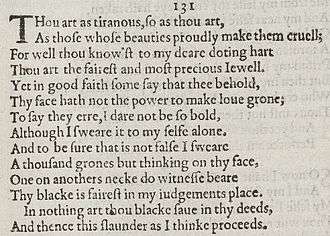

Sonnet 131 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 131 is a sonnet written by William Shakespeare and was first published in a 1609 quarto edition titled Shakespeare's sonnets.[2][3] It is a part of the Dark Lady sequence (consisting of sonnets 127–52), which are addressed to an unknown woman usually assumed to possess a dark complexion.[4][5]

The sonnet, like the others in this sequence, addresses the Dark Lady as if a mistress. It references allegations from unspecified others that her "black" complexion makes her unattractive and rebuts these, but in the final two lines turns the compliment into a backhanded one by admitting that "In nothing art thou black save in thy deeds".[6][7] The sonnet employs the Petrarchan conceit of "tyranny" to imply the power the object's beauty imposes over the sonneteer and argues for her beauty based on the power she exerts over him.[8][9] It also uses the word "groan", another common practice from Petrarch, to superficially reinforce the lover's depth of emotion; but it does so ambivalently, possibly implying the word's connotation of pain or distress, or even its alternate meaning that refers to venereal disease.[10]

Structure

Sonnet 131 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the typical rhyme scheme of the form abab cdcd efef gg and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The 10th line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / A thousand groans, but thinking on thy face, (131.10)

Booth and Kerrigan agree that lines 2 and 4 should be construed as having a final extrametrical syllable or feminine ending.[11][12] Moreover, line 4 potentially exhibits both of the other two common metrical variants: an initial reversal, and the rightward movement of the third ictus (resulting in a four-position figure, × × / /, sometimes referred to as a minor ionic):

/ × × / × × / / × /(×) Thou art the fairest and most precious jewel. (131.4)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus. (×) = extrametrical syllable.

Line 11 also features an initial reversal. Largely because of a number of one-syllable function words in the poem, several lines (1, 4, 5, and 9) have potential initial reversals, depending upon the emphasis chosen. Similarly, lines 1 and 9 potentially contain mid-line reversals, while that in line 13 is surer. Line 3 potentially contains a minor ionic.

The meter demands that line 6's "power" function as one syllable.[13]

References

All references to Sonnet 131, unless otherwise specified, are taken from the Arden Shakespeare third series (Duncan-Jones 2007). In references to this work, p.376–7 refers to a specific page or set of pages; 131.1 refers to the first line of sonnet 131; and 131.1n refers to the note associated with the first line of sonnet 131.[14] Where possible references are double-cited to The Oxford Shakespeare (Burrow 2008), with the same reference system, for convenience.[15]

Notes

- ↑ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- ↑ Duncan-Jones 2007, p. 1.

- ↑ Burrow 2008, pp. 91–3.

- ↑ Duncan-Jones 2007, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Burrow 2008, pp. 131–3.

- ↑ Duncan-Jones 2007, 131.13.

- ↑ Duncan-Jones 2007, p. 376.

- ↑ Duncan-Jones 2007, 131.1n.

- ↑ Burrow 2008, 131.1n.

- ↑ Duncan-Jones 2007, 131.9–10n.

- ↑ Booth 2000, p. 455.

- ↑ Kerrigan 1995, p. 360.

- ↑ Booth 2000, p. 112.

- ↑ Duncan-Jones 2007.

- ↑ Burrow 2008.

Sources

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

- Sonnet 131—facsimile of sonnet 131 from the Internet Shakespeare Editions

.png)